Restoring the Balance:

A State Agency Guide to Taming the Administrative State

Introduction

In a properly functioning constitutional system, elected legislatures make laws that are then implemented by executive agencies. Over recent decades, however, that balance has shifted at both the state and federal levels, with legislatures delegating broad rulemaking powers to executive branch agencies. The result, as scholars have noted, is that some administrators act as lawmakers, blurring the constitutional line between creating and interpreting policy.1 This trend layers complexity into the regulatory code with measurable economic costs: accumulated federal rules are estimated to have reduced annual GDP growth by nearly a percentage point since 1980.2 While some critics warn that efforts to “tame” the administrative state risk weakening effective governance, the expansion of agency discretion is not merely a technical concern but a central question of democratic accountability.3

Yet this tide is beginning to turn. In Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo (2024), the U.S. Supreme Court decisively overturned the longstanding Chevron doctrine, ending the era in which courts routinely deferred interpretations of ambiguous statutes to agencies.4 In its place, courts now exercise independent judgment, a shift that has already produced a sharp increase in judicial scrutiny. In the six months following the Loper ruling, federal courts invalidated nearly 84 percent of new rules under review.5 This doctrinal change interacts with the Supreme Court’s strengthening of the major questions doctrine, which requires clear legislative authorization for agency action on issues of vast political and economic significance.6 These developments signal that agencies can no longer rely on expansive statutory interpretations to justify ambitious regulatory agendas.

Statutory clarity is now more important than ever. With the end of Chevron deference, vague statutory delegations no longer insulate agency interpretations, so directors are exposed to heightened legal challenges if their rules cannot be tied to explicit legislative text.7–8 For state agency directors, this is both a legal and leadership imperative. By proactively reviewing outdated rules, identifying policies that no longer require administrative discretion, and working with lawmakers to enshrine clear statutory standards, state agencies not only reduce regulatory clutter but also reinforce the constitutional separation of powers.9,10 Empirical research on regulatory reform further shows that such efforts yield tangible benefits. Jurisdictions such as British Columbia, Canada, that have adopted systemic review processes significantly cut regulatory volume while maintaining policy outcomes.11 In addition, state agencies that prioritize statutory clarity are better positioned to improve transparency and build durable public trust.

This paper builds upon previous research by the Cicero Institute and offers state agencies a practical, step-by-step guide to unwinding administrative delegation and restoring the legislative prerogative. Drawing on direct experience leading Idaho’s Department of Health and Welfare (DHW), the state’s largest agency, we outline an approach that has been tested in practice and is scalable across states. The strategy focuses on repealing obsolete statutes, conducting zero-based regulatory review, migrating refined rules into statute, and curbing non-statutory policymaking practices.

Through these four steps, state agencies can lower legal risk, reinforce the constitutional separation of powers, and foster a regulatory environment that is lean, durable, and publicly accountable.

Steps to Taming the Administrative State

Step 1. Conduct a Legislative Sprint to Repeal Obsolete Statutes

The first and most straightforward action a state agency can take is to identify and propose to repeal obsolete statutes. Many states, particularly those with part-time legislatures or large, legacy bureaucracies, have accumulated statutory clutter over decades. These provisions often reflect bygone programs, outdated mandates, or duplicative requirements that no longer serve a purpose. Yet, they remain on the books, which creates confusion for the public, expands unnecessary discretion for state agencies, and lends itself to bureaucratic overreach.

To address this, agency leaders should launch a statutory repeal initiative framed as “decluttering” or modernization. Idaho’s DHW demonstrates that even large, complex agencies can complete such a review quickly using a sprint model.

This step has four components:

- Conduct a Comprehensive Statutory Inventory

Compile all statutes relevant to the state agency into a spreadsheet, organized by chapter and section (see Table 1). - Divide and Delegate Review

Assign subject-matter experts in each division or program and give them a 30-day deadline to review their section(s). - Apply Clear Review Criteria

For each section, determine whether it is:- Confirmed Necessary (still actively used);

- Confirmed Obsolete (no longer relevant or duplicative, such as “zombie laws” tied to defunct programs, committees, or superseded statutes); or

- More Research Needed (uncertain cases to be used sparingly and requiring follow-up legal analysis).

- Invite Public Review

Post an early draft of proposed repeals for stakeholder feedback. Early transparency reduces resistance during the legislative session and builds buy-in from lawmakers.

In Idaho, the DHW effort culminated in a legislative package that repealed 150 obsolete statutory sections—the largest such repeal in state history.12 Far from being controversial, the bill received near-unanimous legislative support. This achievement not only removed decades of legal clutter but also signaled to lawmakers and the public that the state agency was serious about good governance. In Idaho, the legislature went further by codifying this review requirement statewide and mandating that all state agencies conduct similar statutory inventories—an enduring legacy of the initiative.13

Table 1. Example Justifications for Obsolete Code

Step 2. Use Zero-Based Regulation to Reduce and Optimize Administrative Rules

Eliminating outdated statutes is a critical first step, but the core of administrative reform lies in overhauling current rules and regulations. Too often, agency rules are maintained by default rather than through deliberate review, which produces provisions that are bloated, inconsistent, duplicative of statute, and largely shielded from ongoing scrutiny.

To address this, Idaho pioneered a process called zero-based regulation (ZBR)—an approach inspired by zero-based budgeting.14 Rather than making incremental edits at the margins, ZBR requires every rule to be justified from the ground up. Agencies treat each regulation as temporary unless affirmatively renewed, as this forces a disciplined review of its necessity, clarity, and statutory basis.

ZBR provides a disciplined, agency-wide framework for determining whether rules are truly necessary, aligned with policy goals, and authorized by statute. Its core components include:

- Five-Year Sunset Reviews

Set expiration dates for all regulations unless affirmatively renewed and ensure every regulation is examined at least once every five years by reviewing 20 percent annually. This prevents regulatory stagnation. - Regulatory “Budget”

Target a 20 percent reduction in word count from the baseline for each rule. This drives clarity and simplicity, especially when coupled with efforts to eliminate provisions that merely duplicate statute. - Regulatory Impact Analyses

Conduct cross-jurisdictional comparisons to evaluate the stringency, complexity, and cost of the agency’s rules against those in other states. These analyses help ensure that the agency adopts the least burdensome approach necessary to achieve its policy objectives.

The benefits of zero-based regulation are measurable. In Idaho, every executive agency participated in ZBR, resulting in an average page count reduction of 38 percent within just three years. Beyond streamlining the code, the process also catalyzed deeper conversations with lawmakers about which policies properly belong in rules and which should be enshrined in statute.

Zero-based regulation is more than a regulatory diet; it is a management philosophy. It shifts the default posture of agencies from “maintain” to “justify,” instilling a culture in which every rule must earn its place. This mindset reinforces the principle that government rules should be narrow, necessary, and firmly grounded in statutory authority, rather than preserved out of habit or convenience.

Step 3. Migrate Optimized Rules to Statute Where Appropriate

Once rules have been reviewed, streamlined, and deemed necessary, the next step is to migrate them into statute where appropriate. This shift strengthens democratic accountability and reduces agencies’ dependence on ongoing rulemaking authority. When rules are embedded in law, any future changes require legislative debate, public hearings, and the transparency of the lawmaking process. These requirements ensure that lasting policies (and amendments to them) are decided by elected representatives rather than by future administrative discretion.

State agencies should approach statutory migration, where appropriate, with precision and care:

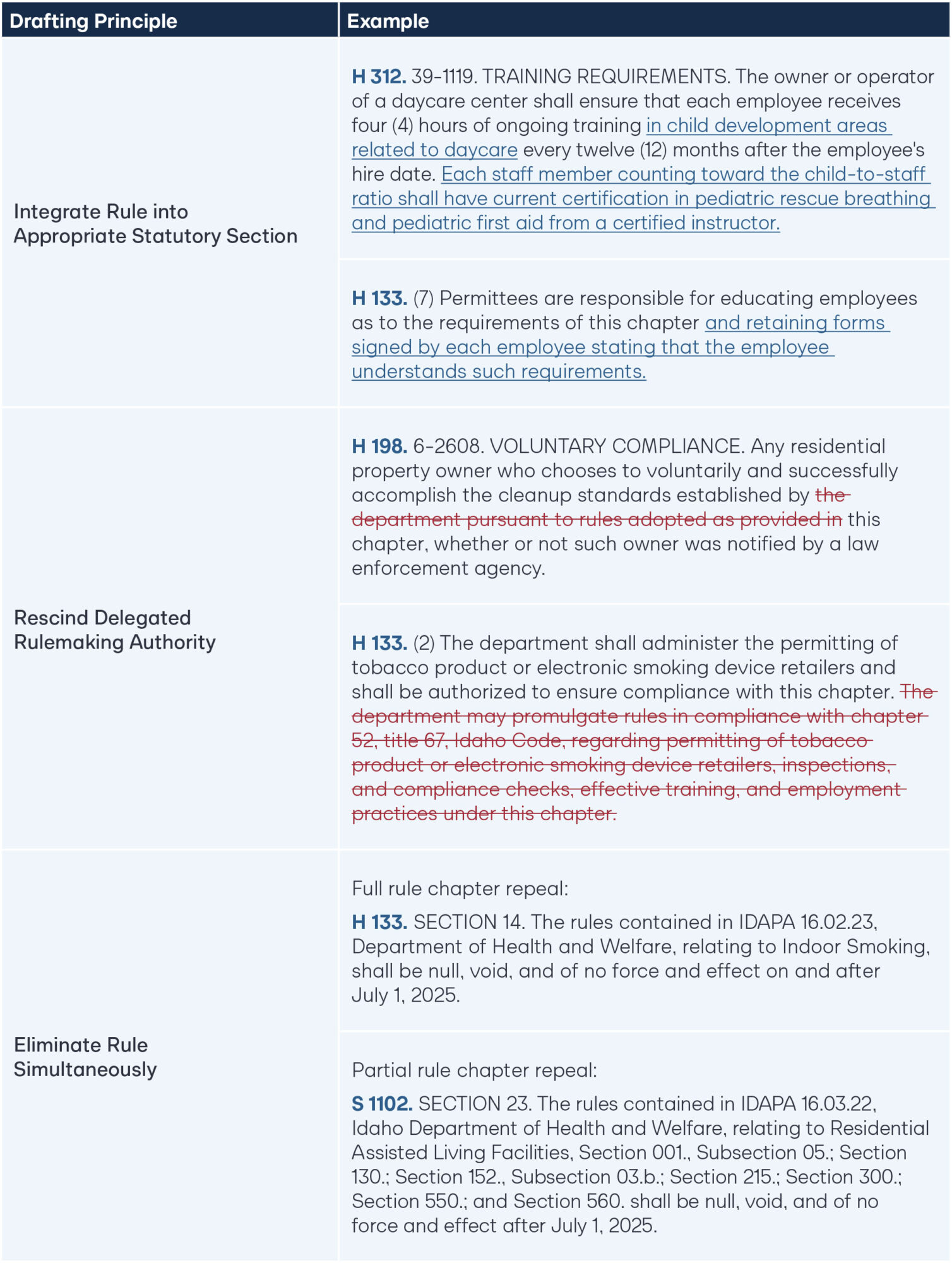

- Integrate Rule into Statute

Move rules into statute in a surgical way by embedding them within existing code, ensuring the law functions as a clear, one-stop reference. - Rescind Delegated Authority

As rules are migrated, repeal the delegation that authorized them. This ensures future updates must come from elected lawmakers to prevent regulatory creep over time. - Repeal the Rule

The same legislation should simultaneously eliminate the existing rule, leaving only the statute in effect. This avoids duplication or conflicts between the new law and leftover regulations.

Table 2. Examples for Drafting Rules-to-Statute Legislation

As legislators seek technical assistance on their own bills, state agencies should proactively identify opportunities to incorporate rules-to-statute provisions into those vehicles. At the same time, state agencies must remain vigilant against efforts to insert new delegations of authority that would undo the progress of statutory migration.

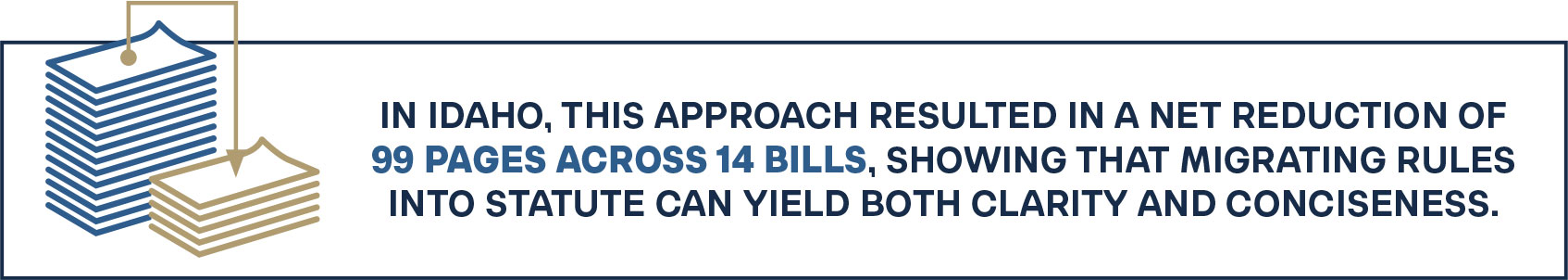

Statutory migration is most effective for longstanding, stable policies such as licensing standards, recurring program requirements, or enforcement protocols. In Idaho, this approach resulted in a net reduction of 99 pages across 14 bills, showing that migrating rules into statute can yield both clarity and conciseness. Lawmakers also valued the agency’s technical assistance in drafting bill language, which fostered a collaborative dynamic built on trust and mutual understanding.

The long-term effect is decisive—once a rule is enacted into law, it cannot be quietly altered through a state agency memo or mid-year rule change. Any revision must go through the legislative process, which preserves elected officials’ authority over the matter in question and creates a more stable business environment across administrations.

Step 4. Minimize Informal Rulemaking and Non-Statutory Policymaking

Even after statutes are streamlined and rules refined, many state agencies continue to operate through a shadow regulatory framework of internal policies, guidance documents, manuals, FAQs, and memos. While useful for day-to-day operations, these materials often blur the line between guidance and enforceable mandates. Over time, they can acquire the practical force of law without legislative input, creating risks for due process and undermining public accountability.

State agencies must carefully inventory and reform these informal regulatory tools. Directors can replicate the process outlined above for statutes by cataloging and reviewing all policies, guidance documents, and manuals on a set timeline. Idaho’s DHW applied this approach to create its first comprehensive inventory of policy documents and eliminated more than 2,000 pages of unnecessary material within a few months.

In some cases, it may also be prudent to codify explicit prohibitions on non-statutory policymaking in sensitive areas. Doing so prevents state agencies from expanding eligibility, expanding benefits, or limiting the scope of practice through guidance or state plan amendments rather than through statute. Table 3 highlights examples from the 2025 Idaho Legislative session that demonstrate how such prohibitions can be structured.

Table 3. Sample Legislation to Curb Non-Statutory Policymaking

These statutory constraints also give state agency directors a valuable shield. When interest groups push for policy changes through guidance or state plan amendments, directors can point to the law requiring legislative approval. This channels debate into the legislative arena to foster clearer and more durable policymaking.

More broadly, state agencies should adopt internal policies requiring all programmatic guidance to be explicitly grounded in statute or rule. This standard should apply to training materials, memos, grant documents, and other operational directives. A recurring review of such materials, both legally and in policy, should be institutionalized as part of sound governance. The goal is to end policymaking by PowerPoint or internal memo: when policies carry real-world consequences, they deserve the same scrutiny as laws and rules.

Outcomes in Idaho

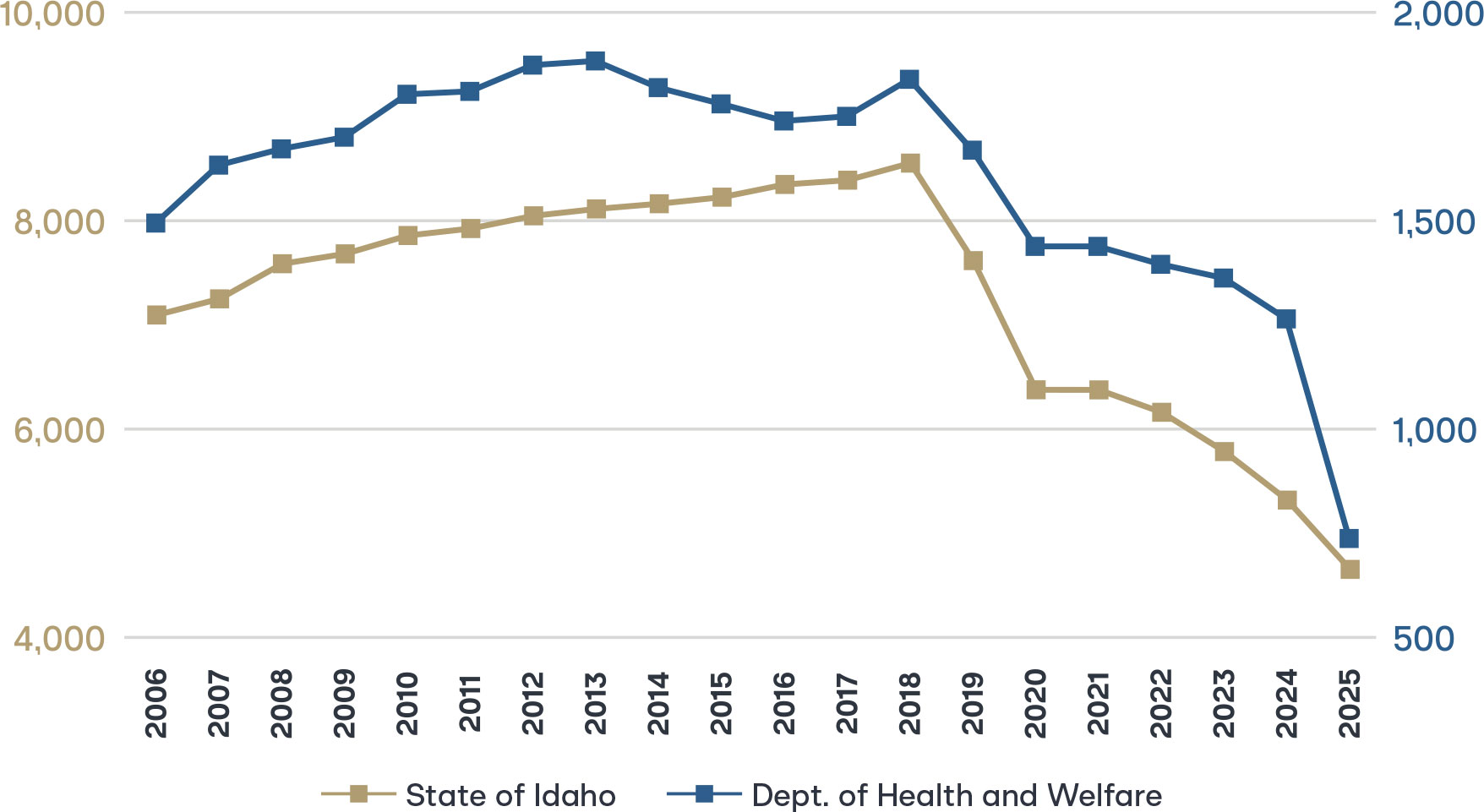

The administrative reforms described above are not merely theoretical—they have been implemented at scale in Idaho, yielding clear and measurable outcomes. Since zero-based regulation (ZBR) was enacted in January 2020, Idaho has significantly reduced its regulatory burden, improved transparency, and reinforced public trust. The regulatory code shrank significantly. Thousands of pages of administrative rules were cut, and agencies eliminated nearly 40 percent of their rules, on average, in just a few years. The combination of ZBR and rules-to-statute migration has resulted in a dramatic drop in the number of pages of administrative rules, with Idaho DHW accounting for more than 90 percent of the state’s regulatory reductions in 2025 alone (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Pages of Administrative Rules for the State of Idaho and DHW

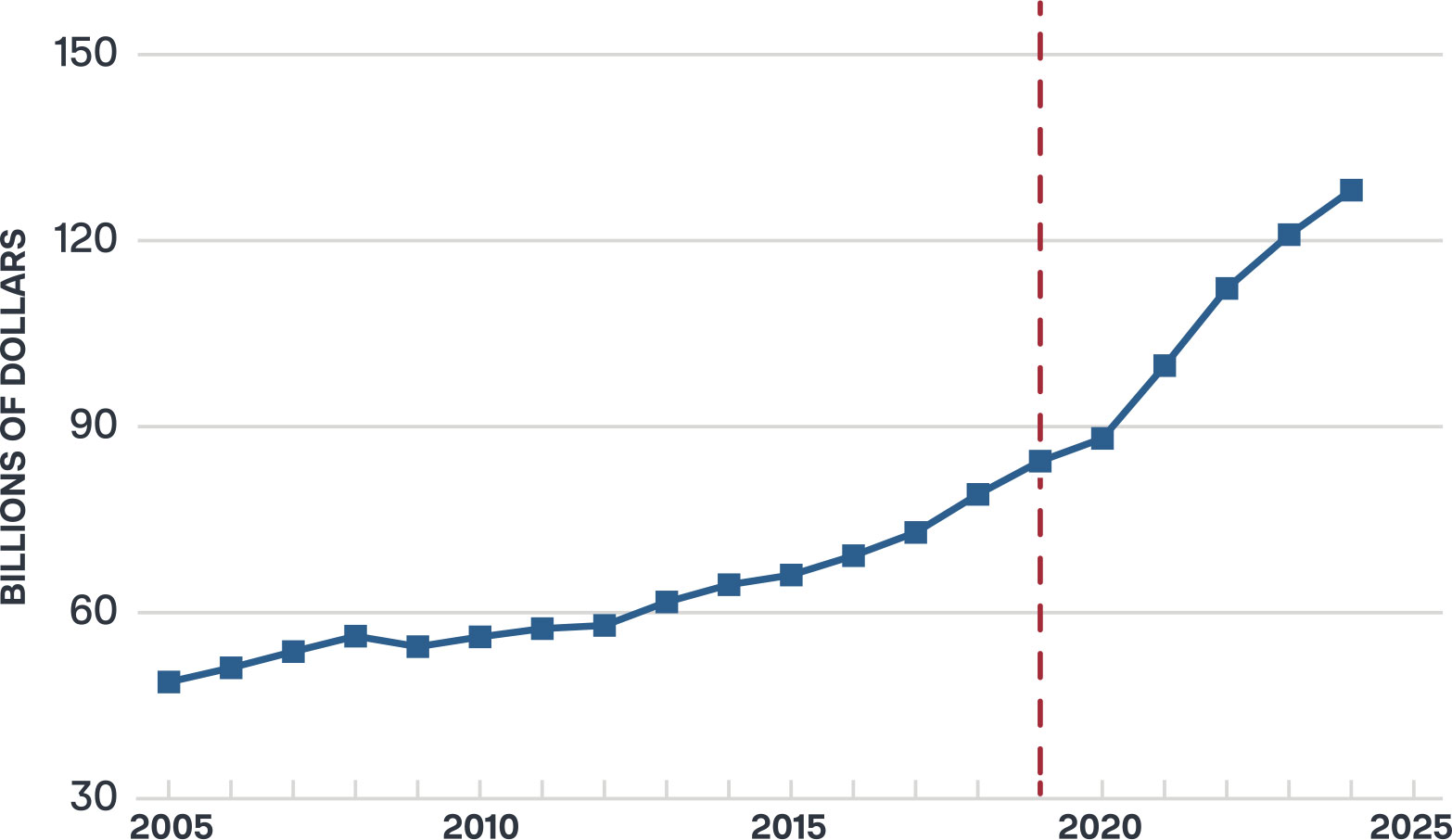

Idaho’s economic growth during the last decade has been striking. From 2014 to 2018, the state’s GDP expanded by 22.6 percent, and between 2018 and 2022 it grew by an even more dramatic 42 percent. The pace was particularly sharp in the immediate post-pandemic period, with GDP jumping 13.3 percent between 2020 and 2021 alone. As shown in Figure 2, the red dashed line marks the enactment of zero-based regulation in 2019, a reform that coincided with this period of accelerated growth. Although Idaho’s economy had already been on a clear upward trajectory since around 2012, the acceleration after 2018 likely reflects the combined influence of the state’s Red Tape Reduction Act and subsequent regulatory reforms. At the same time, it is important to stress that these figures do not isolate a causal effect of regulatory reform. Other dynamics, such as Idaho’s rapid population growth following COVID-19 and broader national economic trends, undoubtedly contributed to these results. Still, the evidence demonstrates that regulatory streamlining occurred alongside a period of robust state economic performance.

Figure 2. Idaho’s GDP (2006–2024)

Source: FRED. GDP not seasonally adjusted.

These reforms also yielded important institutional benefits. In the case of Idaho’s DHW, employees had a better foundation for understanding their programs. Legislators gained transparency into the agency’s processes, which allowed for greater trust in their judgment, and increasingly, they could work with DHW as a partner in policymaking. Most importantly, the public regained control and access over the rules that govern their lives.

This approach offers a scalable solution. Smaller agencies can begin with pilot programs, while larger agencies can phase in reforms across divisions or program areas. Regardless of size or jurisdiction, the four-step model offers a replicable, practical roadmap for reducing regulatory clutter and restoring legislative primacy.

The greatest lesson from Idaho’s experience is that meaningful administrative reform does not depend on federal action or judicial intervention. State agencies already possess the tools to act. With courage, leadership, and collaboration, they can make measurable progress in restoring accountability and curbing the excesses of the administrative state.

Conclusion

The administrative state did not grow overnight, and it will not be tamed overnight either. But the legal landscape has shifted. The end of Chevron deference signals a renewed expectation that agencies live within the bounds of their statutory authority—an expectation matched by a growing public demand for limited, lawful, and transparent government.

State agency directors now have a rare opportunity to lead by example. By eliminating outdated laws, rigorously reviewing existing rules, codifying policy through statute, and cutting off informal regulation, they can reclaim their proper role and reaffirm the constitutional principle of separation of powers. The task is both urgent and demanding—but it is also achievable. Idaho’s experience shows that, with discipline and resolve, state agencies can deliver real reform. The moment is now for other states to follow suit and demonstrate that government can be lean, lawful, and accountable to the people it serves.

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about our fight for policies at the state level that restore liberty through transparency and accountability in American governance.