Three Regulatory Reform Catalysts to Inject Innovation and Speed into Business

Background and Problem

Statutory and regulatory restrictions stifle innovation for both citizens and the marketplace. Whether born through heavy-handed legislative action, imposed through elitist agency bureaucrats and justified as “public protection,” locked in capture from a powerful industry stakeholder, or just plain obsolete rules on the books for years without legitimate review and outpaced by technology and societal changes–regulation slows down American progress and increases unnecessary costs to businesses.

Generally, businesses and citizens should be permitted to innovate and test new technologies and business practices by default—without government permission slips or preemptive agency regulation. However, businesses are typically crammed into a one-size-fits-all, decades-old regulatory box. The standard process to change a law or rule requires the full legislative or rulemaking process. Businesses need a relief valve, a catalyst to begin innovating and providing services immediately. Three critical reform catalysts that inject speed into state government decisions to remove excess burdens can be learned from Idaho. These reforms can give the spark of the American dream the opportunity to catch fire without unnecessary delays.

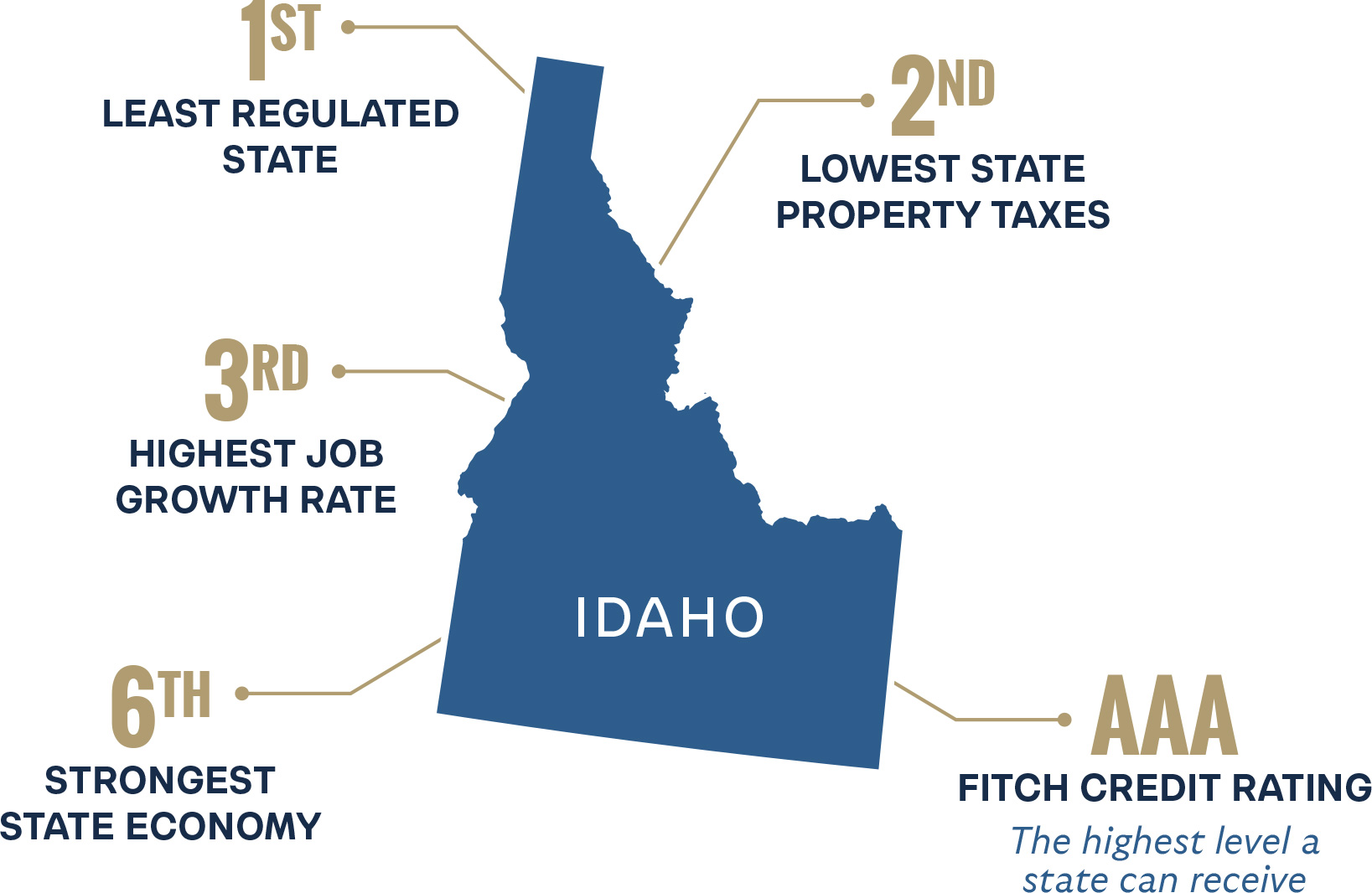

Idaho Governor Brad Little and his administration have been recognized as the most deregulatory administration in America. Idaho has cut through the regulatory fat and ground through the bone of problematic regulations that previously cost businesses exorbitant compliance, lost opportunity, and left citizens with reduced innovation and higher costs. Idaho has reformed occupational licensing, telehealth, pharmacist and psychologist scope of practice, and building and energy efficiency codes. The focus on red-tape reduction has paid off, with Idaho boasting the sixth-strongest state economy, third-highest job growth rate, and second-lowest state property taxes. For the last four years, the well-respected Fitch Rating has affirmed Idaho as an AAA credit rating, the highest level a state can receive.1

In part, these successes stem from processes and procedures delegated by the legislature that allow the state to more quickly remove the regulatory burdens that stifle innovation. Specifically, the Idaho Legislature:

- Granted the Governor emergency rulemaking power to reduce regulatory burdens.

- Authorized citizens to petition for relief from certain statutory restrictions.

- Created a regulatory waiver process for businesses to have regulations waived and then re-open the rule to apply that waiver universally.

These unique catalysts can and should be part of a red-tape reduction discussion for any state that wants to see its businesses freed to innovate and grow.

Catalyst #1: Grant governor emergency deregulatory power to remove excessive burdens on individuals or businesses.

In 2024, the Idaho Legislature passed HB 563, sponsored by Representative Vito Barbieri and Senator Mark Harris, which recalibrated the Administrative Procedures Act’s emergency rulemaking powers of the governor.2 The new law allowed the governor to justify emergency deregulation simply by finding it would “reduc[e] a regulatory burden that would otherwise impact individuals or businesses.” This change allows Idaho’s governor and the executive branch to reduce regulatory burdens on citizens under emergency authority more easily.

The COVID-19 pandemic has plenty of cautionary tales of the perils of centralized executive power granted to the President, Governor, or respective agencies. In Kentucky, Governor Andy Beshear’s ban on in-person church services drew fierce opposition and legal challenges, with a federal judge ruling that it violated religious freedoms.3 In Pennsylvania, Governor Tom Wolf’s business closure waiver process was criticized for arbitrary decision-making and favoritism, undermining trust in public health directives.4–5 Meanwhile, New York’s Governor Andrew Cuomo was heavily criticized for an executive order requiring nursing homes to accept COVID-19-positive patients, a decision many believe led to numerous preventable deaths.6 These examples underscore the contentious balance between public health measures and the preservation of individual liberties during a crisis.

The COVID-19 pandemic also provides many positive examples of governors using their emergency executive authority to make it easier for patients to access healthcare or businesses to remain open. Idaho utilized emergency rulemaking authority during COVID-19 to broadly remove telehealth licensure and technology modality restrictions across all health professions, creating immediate relief and supplanting critical access needs.7 Multiple other states likewise deregulated telehealth licensure with emergency authority during COVID-19.8 Similarly, Idaho used emergency rulemaking authority to remove all remaining scope-of-practice barriers on licensed healthcare professionals to administer vaccinations, empowering non-traditional access points outside of pharmacies and primary care visits through dentists, psychologists, and veterinarians. Emergency rulemaking also removed an arbitrary three-to-one supervision ratio between practicing physician assistants and physicians. All three examples could have been resolved through the legislative branch, but the catalyst for change was the governor’s emergency deregulatory rulemaking authority.

Governors often have big regulatory reform ideas and plans but, once elected, find themselves without the necessary tools to begin cutting the regulatory strings that paralyze their citizens and businesses. While many regulatory reform advocates herald the speed with which Argentina’s President Javier Milei is reorganizing and dismantling the administrative state through presidential “mega decree,” less discussed is how Argentina already grants its president authority to make such bold changes by invoking the constitutional mechanism of Decrees of Necessity and Urgency (DNUs).9 Whether it is day one on the job, in phases throughout the term cycle, or upon request, every state governor should have the authority to issue emergency red-tape reduction rules to remove a regulatory burden that would otherwise adversely impact individuals or businesses.

Catalyst #2: Let citizens petition for a waiver from a regulation that triggers a possible universal waiver for all business.

In 2020, the Idaho Legislature in SB 1283 created a novel pathway for businesses and citizens to request a waiver, variance, or amendment of an existing Idaho administrative rule.10 At the core of the law is the principle that “one-size” rulemaking does not fit all, and a strict application of uniformly applied rules can sometimes lead to unreasonable, unfair, and unintended results. Much like the requirements of the 2024 statutory waiver law, the request process in Idaho law requires the petitioner to demonstrate at least one of the following:

- The rule is unreasonable or causes an undue hardship or burden on the petitioner

- The petitioner’s proposed alternative will provide substantially equal protection of health, safety, and welfare intended by the rule

- The petitioner’s alternative would test an innovative practice or model.11

Agencies that receive a petition must either deny the petition in writing, stating the reasons for the denial or approve the petition and grant a waiver of or variance from the rule, in whole or in part. When an agency grants the waiver, the agency may also specify any conditions, including time limits, for the waiver. If an agency grants a waiver or variance, it must initiate negotiated rulemaking to provide a waiver to all similarly situated persons. Of note, the law prohibits a waiver, variance, or amendment that otherwise violates a statute. The law created a consistent process to reduce the time and resources used by a petitioner and agency to address rule waiver and variance requests.

CASE STUDY

Regulatory Agency Experience with the Rulemaking Waiver Process

On the agency level, the Idaho Board of Pharmacy (the Board) has a decade of successful experience with a similar waiver and variance request process. In the 2011-2012 rulemaking session, the Board formally created a waiver or variance request process to let pharmacies and pharmacists petition them on unreasonable or unduly burdensome rules.12 The process also allows pharmacies and pharmacists to test innovative practices or service delivery models. Highlighted here are three examples and the resulting cascade of the impact of an agency rulemaking waiver process.

1. Authorization of Pharmacy Technicians Administration of Immunizations

In March 2017, Idaho became the first state to authorize pharmacists to delegate immunization administration to pharmacy technicians.13 The increased scope of practice for pharmacy technicians began in December 2016 with a rule waiver request from a partnership between Albertsons Pharmacies and Washington State University.14 Within two years, Rhode Island and Utah also created allowances for pharmacists to delegate immunization administration to trained pharmacy technicians.15 The policy was catapulted in October 2020 when the Trump Administration’s Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued guidance under the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness (PREP) Act authorizing trained pharmacy technicians in all states to administer immunizations in response to COVID-19.16 In one day, the country went from only having a few states recognize pharmacy technicians as immunizers to all 50 states and Washington, D.C. It has been six years since Idaho initially granted a rule waiver. The initial results include a demonstrable safety profile, patient access to more than 50 million immunizations administered by pharmacy technicians nationwide, and more than 25 states creating permanent allowances to the HHS PREP Act authorizing pharmacy technicians to administer immunizations.17,18,19

2. Removal of Multi-State Jurisprudence Exam as Condition of Pharmacist Licensure

In March 2018, The Idaho Board of Pharmacy granted a waiver request to suspend the requirement for a pharmacist to pass a multistate pharmacy jurisprudence exam (MPJE) as a license condition.20 The board expedited this move to avoid delaying the exam’s elimination, leading to the formal adoption of a rule eliminating the MPJE, which became effective in July 2019. The Idaho Legislature approved the rule and passed HB 351 (2018) to clean up statutory references to the examination in code.21 Abolishing the required jurisprudence exam has not resulted in any adverse public safety outcomes. Instead, Idaho has seen a surge in the number of licensed pharmacists, outpacing the growth in neighboring states. Vermont, Michigan, and Alaska also removed the MPJE, and these decisions sparked a national conversation among several pharmacy organizations about creating a more easily transferable pharmacist license, highlighting the particular challenge presented by the state-specific pharmacy law exams (MPJE) as a barrier.22,23,24 Furthermore, the actions beginning as Board of Pharmacy regulatory waiver spurred additional action from the Idaho Legislature in 2023, prohibiting all licensing boards from establishing a jurisprudence examination to demonstrate competence to practice in Idaho.25

3. Authorize Technician Product Verification (TPV) of Compounded Drugs

In September 2023, St. Luke’s Health Systems (SLHS) requested a waiver to allow pharmacy technicians to perform the final product verification check on compounded products.26 Petitioners supported the request with a 2022 observational study conducted by SLHS. The study compared the accuracy of error identification by pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. The results showed pharmacy technicians and pharmacists had similar accuracy, with technicians performing slightly better. In the following months, the Board entered into negotiated rulemaking to pursue a permanent rule change as required by the Administrative Procedures Act. Additional published research has provided more evidence demonstrating the accuracy of pharmacy technicians is not inferior to pharmacists.27 Their conclusions regarding safety results were similar to those of the Board.

In 2019, the Board simplified the waiver and variance process in rule by simplifying the criteria to read, “The board may grant or deny, in whole or in part, a waiver of, or variance from, specified rules if the granting of the waiver or variance is consistent with the Board’s mandate to promote, preserve and protect public health, safety and welfare.”28 The Board also created an emergency rule waiver process in the event of an emergency declared by the President of the United States, the Governor of the State of Idaho, the Board may waive any requirement of the rules for the duration of the emergency.

Statewide Reform: Rulemaking Waiver Authority Applies to Every State Rule

Idaho created its rule waiver process in 2020 to make it easier for citizens to request a waiver—and for agencies to approve it.29 Prior to this change, the Idaho Administrative Procedures Act (APA) only allowed citizens to request that an agency adopt, amend, or repeal a rule. The APA did not allow citizens to request a waiver or variance of an existing rule unless an agency first denied a formal request to adopt, amend, or repeal a rule. Idaho agencies ultimately entertained requests for a waiver, but each agency followed a unique process after the initial denial. These processes were time-intensive for the agency and the petitioner, shifting significant burdens onto the latter.30

Similarly, even when rule waivers were granted after this process, agencies were inconsistent in their approaches to granting additional waivers to similarly situated businesses. Agency boards grappled with common questions such as: Should the waiver apply to other regulated entities? How long should the waiver be granted? Should the waiver have a check-in, reporting, monitoring, or sunset requirement? Does the new waiver request widely differ from the previously granted waiver?

Representative Brent Crane and Senator Jeff Agenbroad sought to standardize the waiver process across all 100-plus rule-making entities.31–32 The new law expedites the waiver request process by letting citizens seek a waiver without first proposing a change to the entire rule. The new law also opens opportunities for other citizens to benefit from a waiver by forcing the agency that grants a waiver to one citizen automatically to consider whether to grant the same or similar waiver to all other similarly situated citizens in the state.

Unelected bureaucrats shouldn’t be allowed to pick singular winners and losers in the marketplace. Therefore, a waiver afforded to one business should be equally provided to other businesses to maintain a competitive balance in the marketplace. After all, by nature, sizable businesses are more likely to have the additional resources to request, supplement, legally defend, and make a written case for a waiver. The Idaho Legislature resolved these considerations by creating a framework within the APA requiring the agency to initiate negotiated rulemaking for a permanent change that will allow all similarly situated persons to derive the same benefits granted to the petitioner. Granting a waiver “win” for one means granting a favorable regulatory “win” for everyone in the regulated community.

Catalyst #3: Let citizens petition a regulatory licensing agency to waive statutory licensing and practice requirements.

In 2024, the Idaho Legislature created an innovative process to let professionals request a waiver from statutory restrictions in occupational licensing laws. SB 1429, sponsored by Senator Lori Den Hartog and Representative Lance Clow, updated the Occupational Licensing Reform Act to allow regulated occupational licensing professionals to request a waiver or variance for a “licensing requirement or practice” that would be otherwise restricted in law.33 The law creates a relief valve for licensed professionals to dismantle decades of regulatory capture that have permeated legislative committees and regulatory agencies. A business can now request—and the agency can grant—a waiver of a licensing requirement that stands in the way of innovation.

Idaho’s law requires the petitioner to demonstrate at least one of the following:

Excess Burden. Due to the petitioner’s circumstances, the licensing requirement or restricted practice is unreasonable and would impose undue hardship or burden on the petitioner with no offsetting public health, safety, or welfare benefit to the public.

Equally Protective Alternative. The petitioner proposes an alternative that, in the opinion of the licensing authority, will afford substantially equal protection of health, safety, and welfare as the waived licensing requirement.

Innovative Experiment. The waiver or variance requested would test an innovative practice or model that will, in the opinion of the licensing authority, generate meaningful evidence for the licensing authority to consider granting similar waivers to all regulated entities.

The most innovative deregulatory agencies often find themselves in a chicken-versus-egg situation on legal authority. Agencies that want to reduce regulatory burdens hesitate when internal attorneys recommend that the agency wait until the legislature changes the law. No matter how compelling, evidence-based, or innovative a request is, agencies thus reject these recommendations, and businesses choose not to waste their time trying to find solutions that would require a waiver from the legal requirements, knowing such requests will be rejected.

Licensing and scope-of-practice restrictions are inherently one of the more contentious legislative debates across states, impacting competition and access to healthcare, workforce, building, construction, and occupational professionals. Empowering regulatory boards to make evidence-based waivers of statute licensing and practice authority restrictions flips momentum towards the requestor and the burden of proof on the lobbying firms paid to keep the status quo. If an agency grants a waiver, Idaho law requires the licensing authority to consider applying that change for all similarly situated persons.

In June 2024, the first Idaho statute waiver (Section 39-1109(4), Idaho Code) was granted by the Idaho Health and Human Services (HHS) Director, Alex Adams.34 A rural childcare facility sought to expand the child-to-staff ratio for daycare facilities, freeing up capacity and opportunity for placement. After the waiver was granted, this waiver was extended to all other childcare facilities, spurring statewide opportunity with immediate uptake from the City of Boise. More Idaho agency statute waiver requests will be reviewed and may be granted in the months ahead. This style of statutory waiver has the potential to unlock decades of expansive gridlocked legislative debates and allow innovation in the laws governing building and energy efficiency, arbitrary supervision ratio mandates, and aligning professionals’ scope of practice with their education, training, and experience.

Statute and Rule Waiver Levers Supplement Mandatory Sunset and Repeal Processes

Generally, state administrative procedures acts dictate the process to adopt, amend, or repeal rules.35 Some states have a mandatory sunset of administrative rules that require a specific level of review and time periods between five to 10 years. The benefits of mandatory regulatory sunset were thoughtfully articulated in a recent publication, Time to Take Out the Regulatory Trash, in which Cicero Institute authors stated:

“First: by default, regulations should not have a permanent lifespan.36 If a legislative body wishes to make a rule permanent, it can codify it into law. But rules written and approved by bureaucrats should not have the permanent status of law. Rules must be subject to regular review with automatic expiration if agencies do not justify the continued need for the rule. The status quo is that inaction means regulations live forever. It should be the opposite: inaction should kill regulations.”

Mandatory sunset and petition for rulemaking are essential levers for individual and business freedom across the states.37 The process to adopt, amend, repeal, or sunset rules takes considerable time in most states. This can delay innovation or experimentation with new business models. To put it simply, why would a business implement, test, or study the benefits of an idea that is directly prohibited by administrative rule? After all, new business models are, more often than not, born into a captive regulated marketplace rather than a free one.38 Citizens and businesses need immediate relief valves to newly adopted rules that aren’t narrowly tailored or working or when an opportunity arises to test an idea on an issue with a long-established rule. A statute and rule waiver process is a critical additional lever toward optimizing administrative rules.

Conclusion

Businesses and citizens should generally be permitted to innovate and test new technologies and business practices by default–without government permission slips or preemptive agency regulation. While decades, and sometimes centuries, of governing state laws and regulations have created captive environments, history has proven that “one-size” legislation and rulemaking do not fit all, and a strict application of uniformly applied rules can sometimes lead to unreasonable, unfair, and unintended results. The pursuit of the American Dream, growth, and individual prosperity can be maximized when governors and state governments create simple processes for both the petitioner and the agency to consider new innovations and remove undue burden.

Catalyst #1 Model Language:

TEMPORARY/EMERGENCY RULES

(1) If the governor finds that reducing a regulatory burden that would otherwise impact individuals or businesses requires a rule to become effective before it has been submitted for review, the agency may proceed with such notice as is practicable and adopt a temporary rule, except as otherwise provided in section [Insert APA Section]. The agency may make the temporary rule immediately effective. The agency shall incorporate the required finding and a concise statement of its supporting reasons in each rule adopted in reliance upon the provisions of this subsection.

(2) Concurrently with the promulgation of a rule under this section, or as soon as reasonably possible thereafter, an agency shall commence the promulgation of a proposed rule in accordance with the rulemaking requirements of this chapter unless the temporary rule adopted by the agency will expire by its own terms or by operation of law before the proposed rule could become final.

Catalyst #2 Model Language:

PETITION FOR ADOPTION, AMENDMENT, REPEAL, OR WAIVER OF RULES

(1) Any person may petition an agency requesting the adoption, amendment, or repeal of a rule.

The agency shall:

(a) Deny the petition in writing, stating its reasons for the denial; or

(b) Initiate rulemaking proceedings in accordance with this chapter.

(2) Any person may petition an agency for a waiver of or variance from a specified rule or rules if the granting of the waiver would not conflict with or violate state law and is consistent with at least one (1) of the following considerations:

(a) In the petitioner’s specific circumstances, the application of a certain rule or rules is unreasonable and would impose undue hardship or burden on the petitioner;

(b) The petitioner proposes an alternative that, in the opinion of the agency, will afford substantially equal protection of health, safety, and welfare intended by the particular rule for which the waiver or variance is requested; or

(c) The waiver or variance requested would test an innovative practice or model that will, in the opinion of the agency, generate meaningful evidence for the agency in consideration of a rule change.

(3) In response to a petition filed pursuant to subsection (2) of this section, the agency shall:

(a) Approve the petition and grant a waiver of or variance from the rule, in whole or in part, and specify whether any conditions are placed on the waiver or variance or whether a specific time period for the waiver or variance is established; or

(b) Deny the petition in writing, stating the reasons for the denial.

(4) An agency shall approve or deny a petition filed pursuant to this section or initiate rulemaking proceedings in accordance with this chapter within twenty-eight (28) days after submission of the petition unless the agency’s rules are adopted by a multi-member agency board or commission whose members are not full-time officers or employees of the state, in which case the agency shall take action on the petition no later than the first regularly scheduled meeting of the board or commission that takes place seven (7) or more days after submission of the petition. If an agency requests additional information from the petitioner, the time period specified in this subsection shall begin anew.

(5) Following the granting of a waiver or variance, the agency shall consider a rule change that will allow all similarly situated persons to derive the same benefits granted to the petitioner.

(6) An agency decision denying a petition is the final agency action.

Catalyst #3 Model Language:

PETITION FOR WAIVER OF OR VARIANCE FROM A LICENSING REQUIREMENT OR RESTRICTED PRACTICE

(1) Any person may petition a licensing authority for a waiver of or variance from a licensing requirement or practice that would be otherwise restricted to a licensee if:

(a) Due to the petitioner’s circumstances, the application of the licensing requirement or restricted practice is unreasonable and would impose undue hardship or burden on the petitioner with no offsetting health, safety, or welfare benefit to the public;

(b) The petitioner proposes an alternative that, in the opinion of the licensing authority, will afford substantially equal protection of health, safety, and welfare intended by the particular licensing requirement for which the waiver or variance is requested; or

(c) The waiver or variance requested would test an innovative practice or model that will, in the opinion of the licensing authority, generate meaningful evidence for said licensing authority in consideration of a licensing requirement or restricted practice change.

(2) In response to a petition filed pursuant to subsection (1) of this section, a licensing authority shall:

(a) Deny the petition in writing, stating the reasons for the denial; or

(b) Approve the petition and grant a waiver of or variance from the licensing requirement or restricted practice, in whole or in part, and specify whether any conditions are placed on the waiver or variance or whether a specific time period for the waiver or variance is established.

(3) A licensing authority shall approve or deny a petition filed pursuant to this section or initiate proceedings to review the petition within twenty-eight (28) days after submission of the petition. Provided, however, if the licensing authority is governed by a multi-member licensing authority board or commission whose members are not full-time officers or employees of the state, the licensing authority shall act on the petition no later than the first regularly scheduled meeting of the board or commission that takes place seven (7) or more days after submission of the petition. If a licensing authority requests additional information from a petitioner, the time period specified in this subsection shall begin anew.

(4) Following the granting of a waiver or variance, a licensing authority shall consider a change that will allow all similarly situated persons to derive the same benefits granted to the petitioner.

(5) Any licensing authority decision denying a petition shall be considered a final agency action.

(6) This section shall not allow waivers or variances that would grant an initial license to an individual who does not meet the statutory requirements for an initial license.

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about our fight for policies at the state level that restore liberty through transparency and accountability in American governance.