States Need to Update Telehealth Laws to Improve Access to Mental Health Services

Introduction

The availability of interstate telehealth exploded during the pandemic when many states removed in-state licensing requirements for healthcare practitioners, allowing them to practice across state lines temporarily. As a result, millions of Americans tried telehealth for the first time. Since then, studies have shown that across all specialties, the behavioral healthcare arena had some of the highest adoption, with as many as five out of 10 visits being conducted by telehealth.1

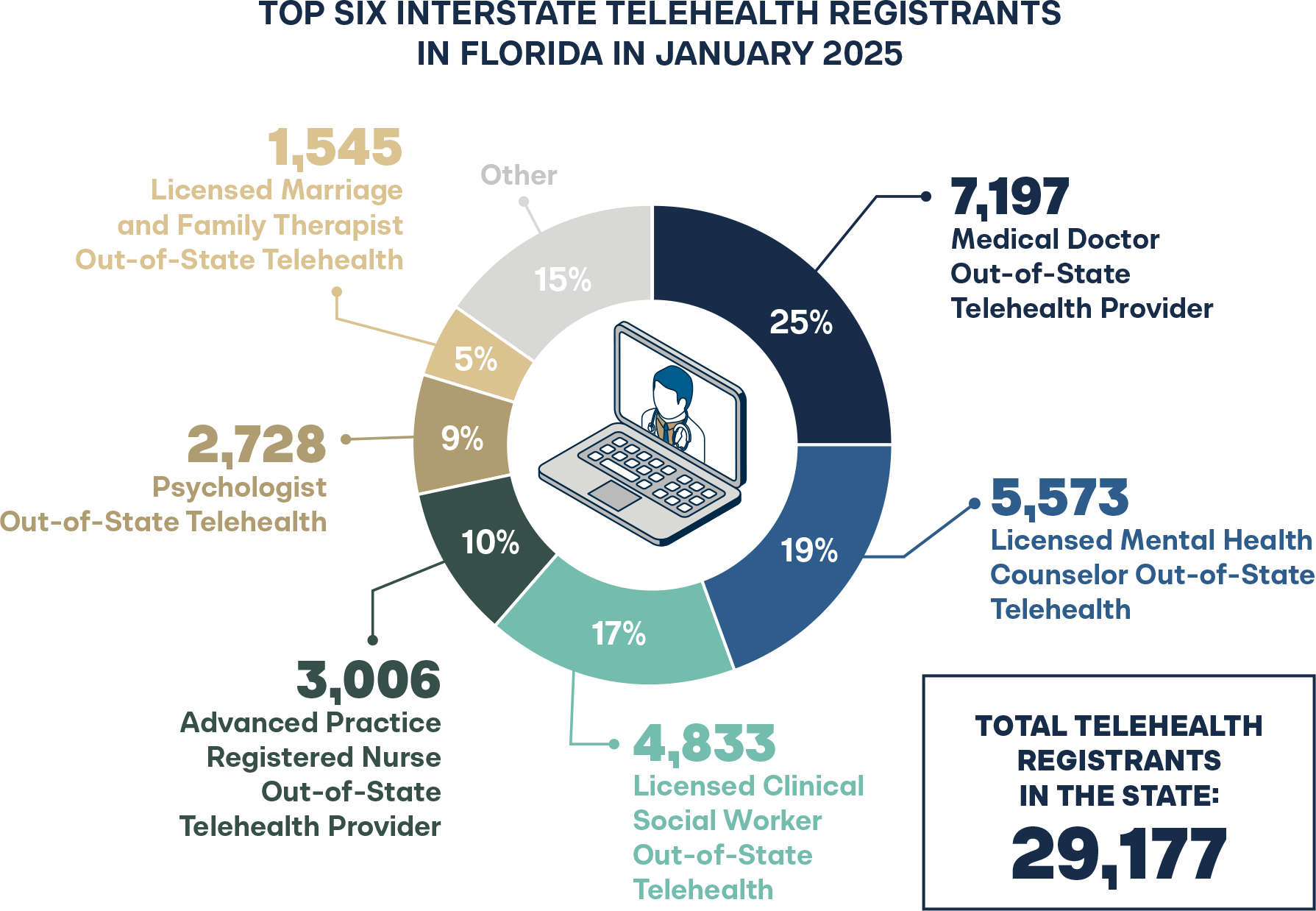

In addition, behavioral health providers have embraced the opportunity to provide telehealth care across state lines when available. Some states, such as Florida, have modernized telehealth to make it easier for providers to practice across state lines. As of January 2025, behavioral healthcare professionals made up the largest number of out-of-state practitioners registered in Florida for interstate telehealth, with counselors and social workers making up two of the top three provider types, just behind medical doctors.

Counselors and social workers comprise almost 70 percent of the behavioral healthcare workforce and, therefore, deliver the majority of care in the country.2 These licensed professionals with masters-level educations provide critical behavioral health services to many high-need populations, such as low-income families, those experiencing homelessness, veterans, and those who face challenges with mental illness and/or substance use disorders.

Since the pandemic, the rate of policy changes in telehealth has slowed each year.3 Yet, the most active area of policy change revolves around behavioral health, as the issue remains at the top of many state legislative agendas, with an increased demand for these services and many states facing a shortage of qualified professionals to meet it.4 Instead of broad-based reforms, most of the changes have been around narrow compacts or smaller tweaks in current law.

Allowing licensed practitioners to easily practice across state lines and not requiring an in-state license has proven to be safe and effective.5 Despite this, most states either require an in-state license or their interstate telehealth laws only apply to physicians (i.e., often defined as telemedicine) and block many non-physician practitioners from practicing. There can also be significant requirements that serve as barriers to patient access such as: burdensome amounts of independent or supervised practice, jurisprudence exams, duplicative background checks, and other unnecessary barriers for practitioners who have already passed their exams, are licensed and in good standing, and should be able to practice.

States should closely examine their telehealth laws to ensure greater access to behavioral healthcare through telehealth. This brief examines six states to illustrate the current policy state on behavioral health access over telehealth, with a particular focus on counselors and social workers.

Emerging Licensing Trends

Interstate Telehealth & Multiple Pathways to Practice

Very few states remove in-state licensing requirements, implement holistic telehealth registration, or have reduced their barriers to licensure to provide as many straightforward pathways as possible. However, there are a few states that have made it a priority to open new care options for their residents.

STATE HIGHLIGHT: FLORIDA

Florida has one of the most comprehensive registration processes for telehealth across state lines that removes the requirement of an in-state license for physician and non-physician practitioners, including the whole behavioral healthcare workforce.6 Apart from social workers and counselors, this also includes psychologists, marriage and family therapists, and more. Florida also participates in the counseling compact but not the social worker compact.

Some critics of interstate telehealth contend that state boards may not have the power to effectively discipline out-of-state providers with complaints. Yet, a 2023 report found that when Florida updated their telehealth laws in 2019, there were relatively few complaints against providers in another state.7 During the same two-and-a-half year period, in-state providers had 57 complaints while out-of-state providers had only 16. The report demonstrated that state boards can receive and act on complaints of out-of-state providers, if necessary.

STATE HIGHLIGHT: COLORADO

In 2024, SB 141 was signed into law, and beginning in 2026, Colorado will create an updated pathway for out-of-state telehealth providers including social workers and counselors who currently must apply for an in-state license by endorsement.8

This new law allows qualified out-of-state practitioners to register and practice in the state without obtaining a full Colorado license. It reduces barriers to practice in Colorado with lowered fees, quicker turn-around, and recognition of valid out-of-state licenses.

Many providers seek licensure in Colorado. For example, approximately one in four of all social worker licenses granted in Colorado are to out-of-state providers.9 Additionally, Colorado participates in both the counseling compact and social worker compacts.

STATE HIGHLIGHT: ARIZONA

Arizona ranks almost last for behavioral health workforce availability, meaning across-state-line telehealth is critical.10 In 2021, Arizona’s original interstate telehealth law (HB 2454) included a wide range of behavioral healthcare professions (i.e., marriage and family therapy, professional counseling, social work, and substance abuse counseling). However, the final version only allowed psychologists to register for interstate telehealth along with physician practitioners like psychiatrists.11 Even though these professions were barred from interstate telehealth registration and need an in-state license to practice, Arizona has decreased barriers and adopted multiple pathways for licensed social workers and counselors in another state.

Arizona passed SB 1089 in 2021, which significantly reduced licensure requirements for supervised practice (3,200 to 1,600 hrs.) for counselors, social workers, and other behavioral healthcare professionals, which is considerably less than the majority of state and compact requirements.12 Take, for instance, the Social Work Compact that requires at least 3,000 hours of post-graduate supervised clinical practice.13

Currently, Arizona implements license by endorsement for out-of-state licensed practitioners as long as they have at least one year of independent practice.14 Also, the time to endorse a license in the state only takes about one week as compared to some states, which take at least three months to process a license for individuals already licensed in other states. Apart from this, Arizona participates in interstate compacts for both counselors and social workers. Additionally, the state drops the registration and the in-state licensure requirement for providers serving patients or “snowbirds” who are residents in other states and whose main behavioral healthcare provider is out-of-state.15

Interstate Compacts

When multiple states agree upon uniform standards for occupational licensure and attempt to streamline the process for licensure among those states, it is often known as an “interstate compact.”16 Interstate compacts are designed for providers working in multiple states or licensed providers seeking to move to another state. While compacts are a positive step forward, they can have limitations as they are time-consuming, expensive, and limited to only member states. Additionally, compact laws may be less attractive to states with more flexible, patient-centered health systems (e.g., states with broader scopes of practice or fewer requirements for independent practice) or impact unique state-based healthcare considerations.

Behavioral health-related compacts have exploded in the licensing space over the last few years. As of August 2024, 37 states have passed legislation to join the Counseling Compact.17 Twenty-two states participate in the Social Work Licensure Compact.18

One driver of these compacts is that military spouses comprise a large proportion of these professions, and occupational license portability is critical for these families that move from state to state.19 Social workers alone comprise 45 percent of the mental health workforce within the Department of Defense and see 42 percent of all encounters in the military that involve mental health or substance abuse problems.20

Though compacts are a solution to modernize occupational licensing, generally, most compacts are shy of true interstate telehealth. Limited to only participating states, compacts can have a steep up-front “entrance cost,” which must be obtained before paying additional fees for each state in which the practitioner wants to gain privileges to practice.

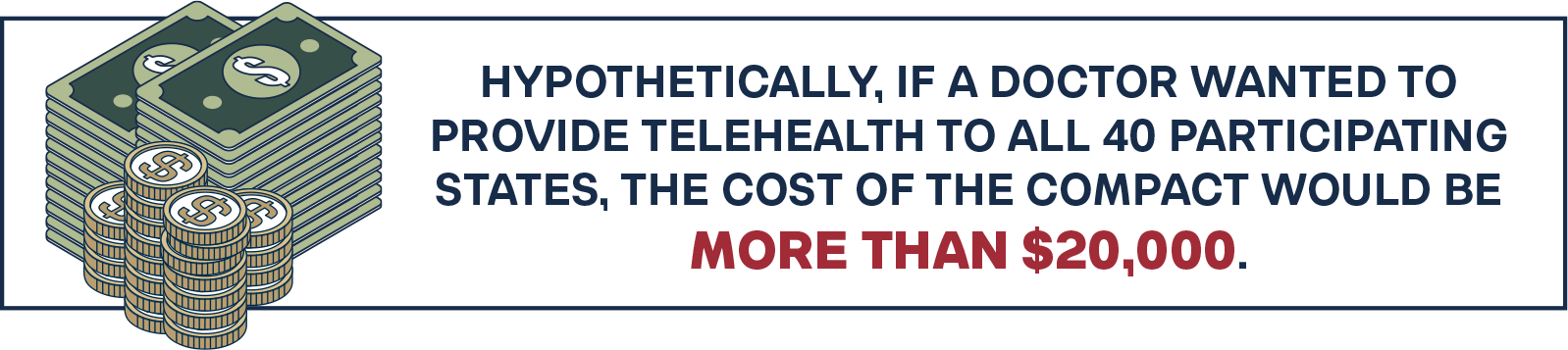

Take, for instance, the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact (IMLC) for physicians, which costs $700 to enter initially and then additional costs for each individual state, which range from $35 to a whopping $800 depending on the state in which the doctor wants to practice.21 Hypothetically, if a doctor wanted to provide telehealth to all 40 participating states, the cost of the compact would be more than $20,000. Notably, healthcare licensure is not a one-time cost but is renewed as often as annually, every two years, or depending on state licensure rules.

Certainly, a $20,000 licensure fee, even for a high-paying occupation such as a physician, is worth noting. Social worker state licensure fees can range from roughly $40 to over $300 per state, so it would cost a social worker a few thousand dollars depending on the state and how many states the practitioner seeks to work in.22 For behavioral healthcare professionals who often have lower-paying positions, such fees create a significant barrier to practice. According to recent data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, social workers make an average of $68,800, and counselors make an average of $52,360.23–24 Compacts are expensive for individual providers and costly to pass, as even proponents of such laws must lobby in every single state for adoption, often requiring multi-year fights.

Healthcare associations and boards support compacts versus a more flexible interstate option because compacts protect their control and revenue. For example, The American Medical Association, the largest association and lobby group of physicians, stated the IMLC was not designed to facilitate telehealth across state lines. Instead, “the compact is the first line of defense against troubling federal proposals to create a federal telemedicine license, or to change the site of practice from where the patient is located to where the physician is located for purposes of telemedicine… The compact is intended to prevent just that.”25

STATE HIGHLIGHT: DELAWARE

One of the few states with mental health interstate telehealth registration, Delaware removes instate licensing requirements for out-of-state practitioners.26 However, Delaware bars out-of-state practitioners who reside in a compact state from interstate telehealth registration and forces them to purchase a multi-state license from the relevant compact. This forcible compact is not true for interstate telehealth and may be significantly more expensive for out-of-state practitioners who choose to provide care in this state alone.

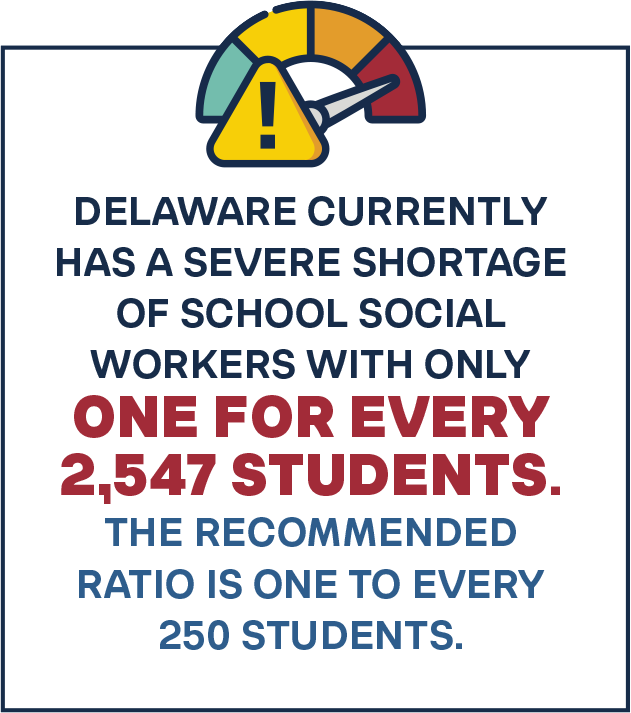

According to a 2023 report, Delaware currently has a severe shortage of school social workers with only one for every 2,547 students.27 The recommended ratio is one social worker to every 250 students. As more states join the Social Work or Counseling Licensure Compact, the number of potential practitioners who could easily register and provide services to Delaware residents may decrease due to the higher fees that are associated with a multi-state license and, overall, deter potential providers from providing critical behavioral health services in this state.

The Delaware Board of Mental Health and Chemical Dependency Professionals and Social Work Examiners currently dictates that practitioners who reside in states that participate in the Social Work or Counseling Compact are barred from registering with the state although compacts are two to three years from being implemented.28–29 For Delaware, this means that the forced compact rule currently excludes and will continue to prohibit out-of-state providers from compact states from the ability to register and provide services without applying for an in-state license. The counseling and social work compact’s delay in issuing privileges neatly demonstrates the potential problems compacts pose for states.

Burdensome Practice Requirements

Several states implement license by reciprocity or license by endorsement, meaning workers can obtain an in-state license as long as the practitioner is licensed and in good standing in the state in which they currently reside. Both processes can be accessible or extremely stringent depending on the state’s requirement for duplicative background checks, jurisprudence exams, or, most notably, hours of supervised or independent practice.

Even though social workers and counselors have a similar two-tier licensing process and are generally licensed after completing their master’s degree plus two years of supervised clinical practice, many states implement unnecessary and burdensome supervised and independent practice requirements.

ROOM FOR IMPROVEMENT: MINNESOTA

Minnesota principally has interstate telemedicine, meaning both social workers and counselors need an in-state license to practice.30 Social workers receive approval through license by endorsement, and counselors receive approval through license reciprocity.31–32 Both processes require at least 4,000 hours of supervised practice, significantly longer than many state and compact standards. In the case of social work, only 17 percent of states require this supervised practice amount or higher.33

To obtain licensure in Minnesota as a clinical social worker or professional clinical counselor, many licensed out-of-state practitioners may have to prove active independent practice for at least five years or work at a lower-level license in Minnesota, inhibiting residents from accessing their unique skill set.34

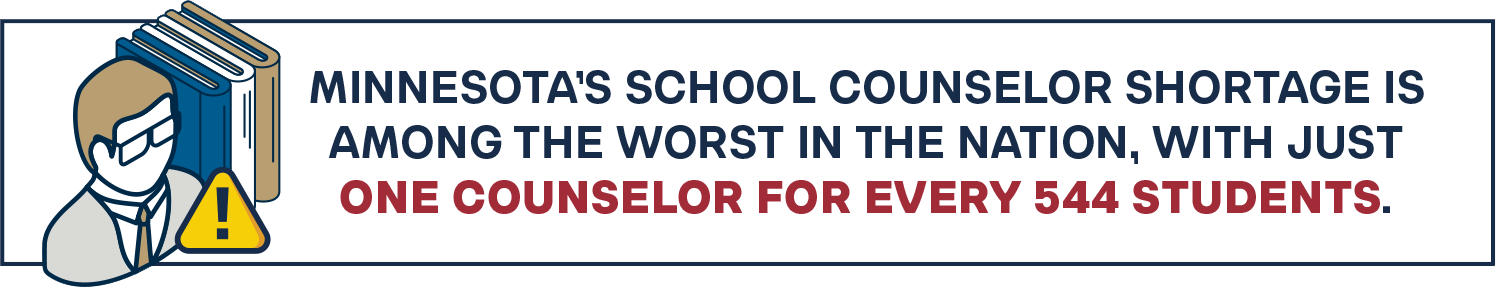

Eighty percent of all of Minnesota’s counties qualify as mental health shortage areas, which is particularly acute in rural areas.35 The shortage is especially concerning for children, who often rely on schools for mental health support. According to data from the American School Counselor Association, Minnesota’s school counselor shortage is among the worst in the nation, with just one counselor for every 544 students.36

To improve access to care, especially for rural communities, Minnesota policymakers should make license reciprocity more attainable for interstate social workers and counselors and align it with the more accessible standards set by compacts and in-state providers.

No Interstate Telehealth or Limited Exceptions

Despite the critical need, many states do not implement interstate telehealth, compacts, or only allow cross-state licensing except under extremely limited circumstances (e.g., during emergency declarations, life-threatening conditions for the patient, or for consultation purposes) which has implications for patients, providers, and caregivers alike. Some states that completely lack a specific pathway to interstate telehealth include North Carolina, Montana, and Mississippi.

Recent research published by The Office of Behavioral Health, Disability, and Aging at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services demonstrates that behavioral healthcare providers may have significant confusion about their ability to deliver telehealth services across state lines due to state-specific licensing restrictions, which often disrupt care, forcing providers to determine on a state-by state-basis whether they have authority to deliver services or whether there are instances providers are legally unable to provide urgent care to individuals in crisis.37 This is especially relevant for telehealth providers working with those struggling with substance use disorder.

ROOM FOR IMPROVEMENT: ALASKA

Alaska principally allows interstate telemedicine under limited circumstances, which applies to physicians, but bars out-of-state non-physician practitioners from practicing (e.g., counselors, social workers, psychologists, and others). Alaska passed legislation in September 2024 (SB 91) to include other providers; however, they cannot practice independently and can only provide care under certain criteria.38 The new law states that non-physician practitioners must be part of a multidisciplinary care team under a physician, and they can only provide ongoing treatment, follow-up care, or a visit for a life-threatening condition. The physician must have conducted a previous in-person visit for ongoing treatment or follow-up care. Also, Alaska does not participate in any of the compacts.

Given the state’s rural nature and geographic separation from the lower 48 states, access to telehealth is particularly important for Alaskans. In terms of mental health, Alaska’s suicide rate of 30.8 deaths by suicide per 100,000 is more than double the United States’ average rate of suicide of 14.1.39 Despite the clear need for increased access to mental healthcare, the mental health workforce in Alaska remains low at just 12.1 percent of mental health needs met (compared to the U.S. average of 27.7 percent), according to research by the Kaiser Family Foundation.40

Alaska’s restrictive law barring out-of-state fully qualified counselors, social workers, or psychologists from providing telehealth independently unjustifiably exacerbates Alaska’s mental health crisis and mental health worker shortage.

Discussion

This short analysis revealed key trends policymakers can learn from to ensure patients can access the nation’s most common out-of-state telehealth providers. Today, state laws demonstrate significant barriers around interstate telehealth for counselors and social workers. Sadly, the majority still bar behavioral healthcare practitioners from practicing without an in-state license or require huge amounts of unnecessary supervised or independent practice and duplicative background checks, among other obstacles.

Theoretically, license by endorsement, license by reciprocity, universal recognition, or having a registration process without requiring an in-state license should vary in degree of licensure freedom. However, this analysis revealed that, depending on how it is implemented, many of these methods can be flexible or extremely prohibitive by adding new barriers, which may be more burdensome than the initial licensure process.

Apart from social workers and counselors, the barriers to interstate telehealth seen in this analysis also occur among other behavioral healthcare professions. A series of recommendations have been compiled to ensure key behavioral healthcare practitioners can easily practice across state lines:

Recommendations for Policymakers

1) Implement an automatic and straightforward process:

Lawmakers should remove common protectionist barriers such as burdensome hours of supervised or independent practice, duplicative background checks, jurisprudence exams, or repeat licensing exams. As long as these individuals have passed a licensing exam, completed their supervised practice, and are licensed and in good standing, patients should easily be able to access these out-of-state behavioral healthcare practitioners.

2) Do not rely on compacts alone or mandate participation in compacts:

States should not rely on compacts alone or mandate participation to ensure across-state licensing for these professions or any profession. Even though the social work and counseling compact is a step forward in liberating patients from protectionist licensing laws, the compacts are still at least two years from issuing privileges to practice.

Secondly, states that solely implement compacts unwittingly may be erecting barriers to entry for practitioners, such as excessive costs, unnecessary time delays, barring providers from nonmember states, and sometimes, having more restrictive standards than non-participating states. A multi-state license plus additional fees (depending on the state of practice) is generally more expensive and could bar practitioners who want to provide telehealth services in just one or two states.

3) Do not implement unnecessary amounts of supervised or independent practice (Generally, these individuals already have at least two years of supervised practice):

At a minimum, states that have significantly higher requirements for supervised practice (more than 3,000 hours) should consider reducing and more closely aligning them to other states to foster multi-state practice and remove additional independent practice requirements for licensed professionals who have already completed their appropriate supervised clinical practice.

Secondly, states like Arizona that have significantly reduced supervised practice requirements to obtain licensure should be tracked to determine whether they are worth replicating in other states.

4) Reduce the cost of multi-state practice:

Fees can add up and can significantly hinder behavioral healthcare professionals in lower-paying positions from practicing in multiple states.

5) Include all behavioral healthcare provider types:

To improve access to behavioral healthcare, states should not cherry-pick which provider types have streamlined processes. Rather, creating reasonable and consistent standards for social workers, counselors, psychologists, marriage and family therapists, and addiction counselors can reduce confusion stemming from regulatory burdens.

6) Remove payment parity or let it phase out:

Numerous states currently have coverage and payment parity mandates for telehealth. Coverage parity often mandates that all services that can be made available over telehealth must be covered by insurance. Payment parity mandates that telehealth services are paid at the same rate as in-person office visits, often including facility fees.

States should avoid coverage and payment mandates as telehealth allows for innovation in care delivery that can often be delivered for less. As many patients have high deductibles, they are being mandated to pay more for the service, and a higher cost to the patient will result in many avoiding accessing care.

If states decide to allow for more across-state-line behavioral health over telehealth, which should increase access, they should think about the impact of such a policy change on the cost of services for patients if they have telehealth mandates. More utilization could mean more spending and higher insurance premiums the next year.

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about our fight for policies at the state level that restore liberty through transparency and accountability in American governance.