Aligning Profit with Outcomes in Private Prison Procurement

Introduction

Privately-operated prisons are among the most controversial instances of privatization of a government service. Questions of whether companies should profit from incarceration, or what role private prisons have played in the expansion of so-called ‘mass incarceration,’ are now common in public and political discourse about America’s criminal justice system. While some states have a larger share of their prison population in private prisons than others, a total of about 90,000 people are held in private state prisons in the United States.1 Despite housing only around eight percent of the country’s imprisoned population,2 the $4 billion industry is the target of disproportionate criticism.3

Departments of corrections seek efficiency, or at least the façade of efficiency; this is where private corrections claims to thrive. The industry argues it can provide the same or better standards of care and confinement than the public sector at the same or lower cost. In the words of one private prison operator, Management & Training Corporation (MTC):

Since 1987, MTC has been operating safe and secure correctional facilities and preparing incarcerated men and women for successful reintegration into their communities… All prisons must be held to the highest standards in providing clean and well-maintained facilities, quality and timely health care, and programs that are effective in preparing men and women in custody for reintegration into society.4

A majority of states and the federal government currently choose to contract for performance in prison and detention management. Why do they do it? For the same reason government agencies contract for any other service: to provide the public with high-quality services in a way that is fiscally responsible and highly accountable.5

The root of the issue is not really whether private prisons are more cost effective or better rehabilitators than public prisons; instead, it is that private prisons are not paid based on the outcomes they achieve. Traditionally, private prison contracts are dependent on the number of beds that are occupied each day or the number of total beds in the facility and so-called “guaranteed minimums” of occupied beds. Theoretically, these misaligned incentives could drive private prisons to deprioritize the rehabilitation of inmates, thereby negating any expectation of improved outcomes, such as reduced criminality, in lieu of focusing on the number their facilities can or do incarcerate.

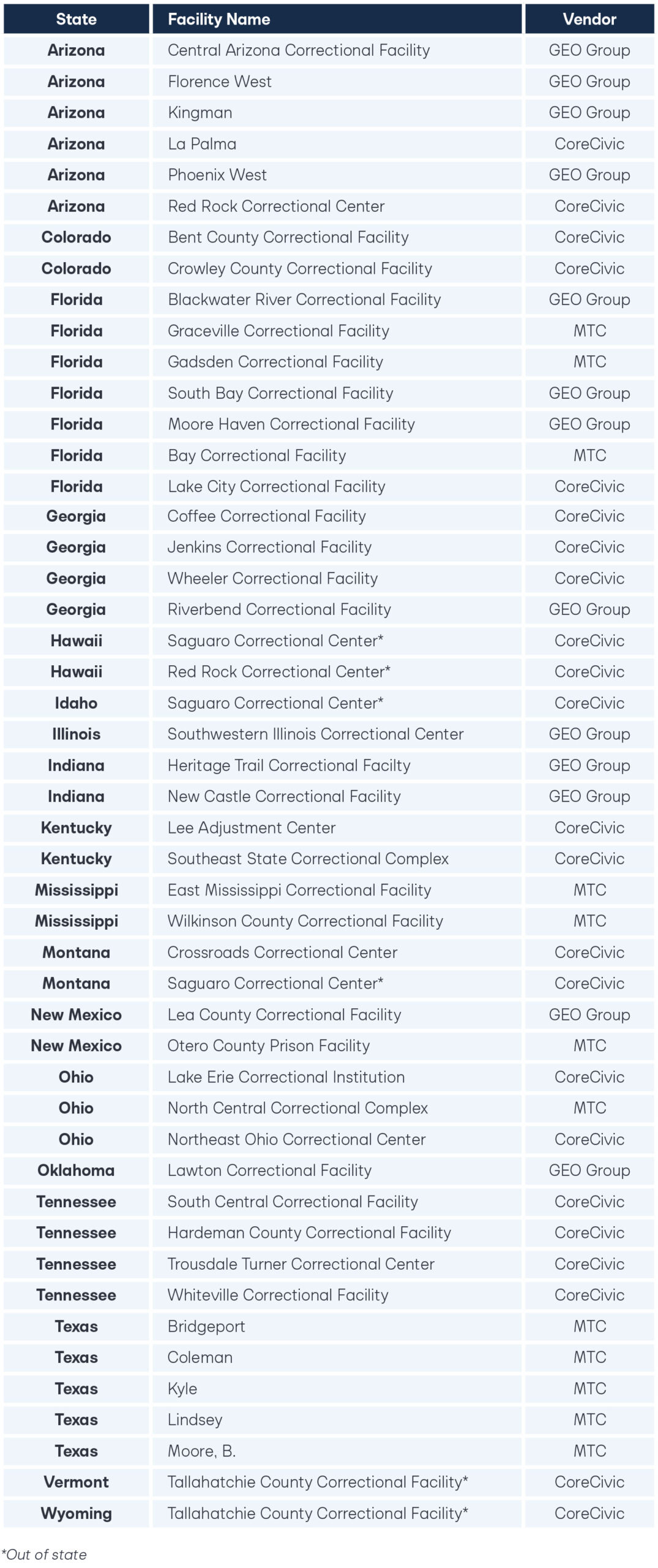

A lesser-known but equally problematic issue in private prison contracting is the effective oligopoly of providers: CoreCivic, The GEO Group, and MTC. As of 2014, these three firms accounted for 96 percent of all private prison beds in the nation, with CoreCivic alone controlling more than 50 percent of all beds.6 As noted by Mumford, et al (2016), though private prisons do technically compete with public prisons, “the extent to which private firms compete with each other for prison contracts is fairly minimal because there are few firms in the business.”7

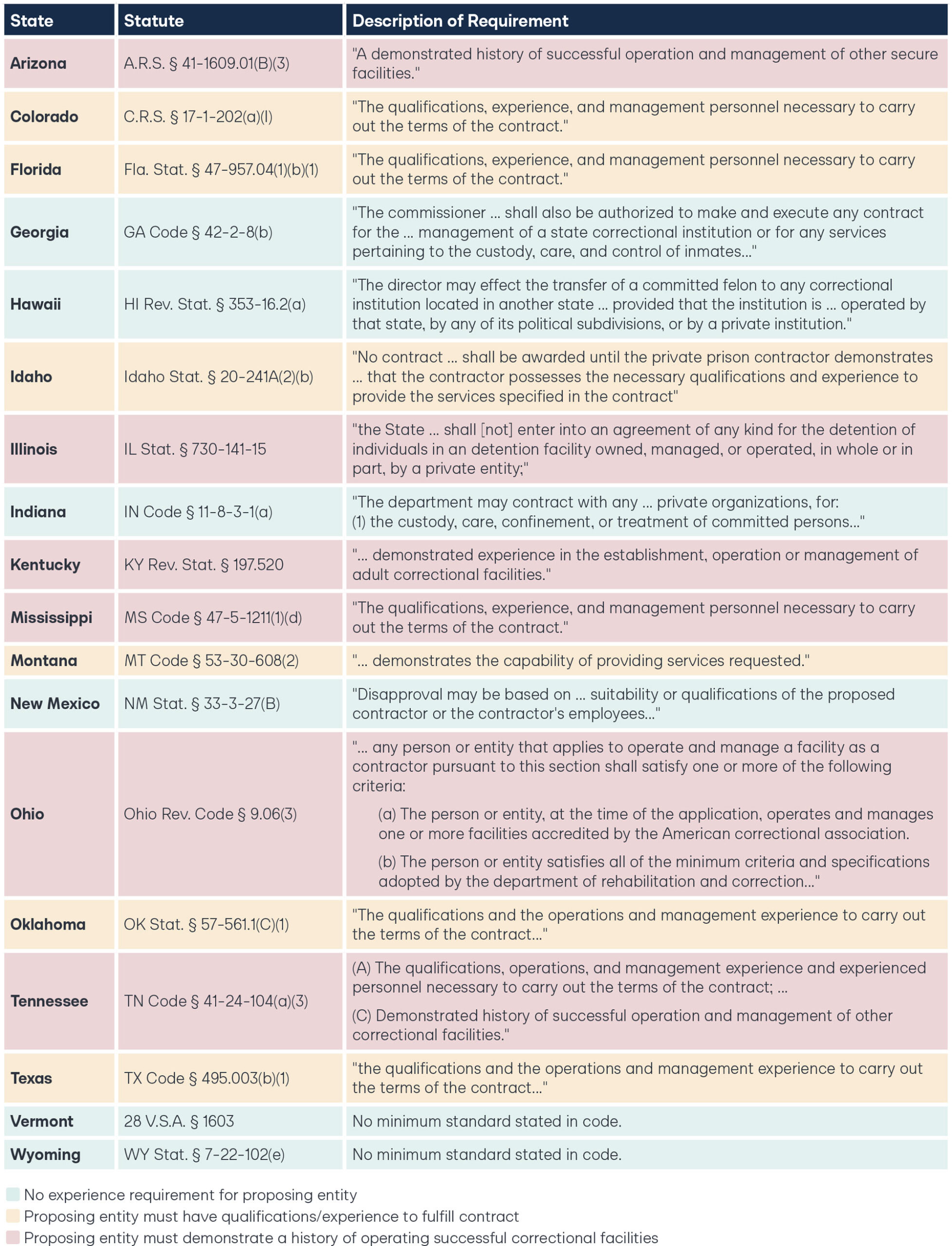

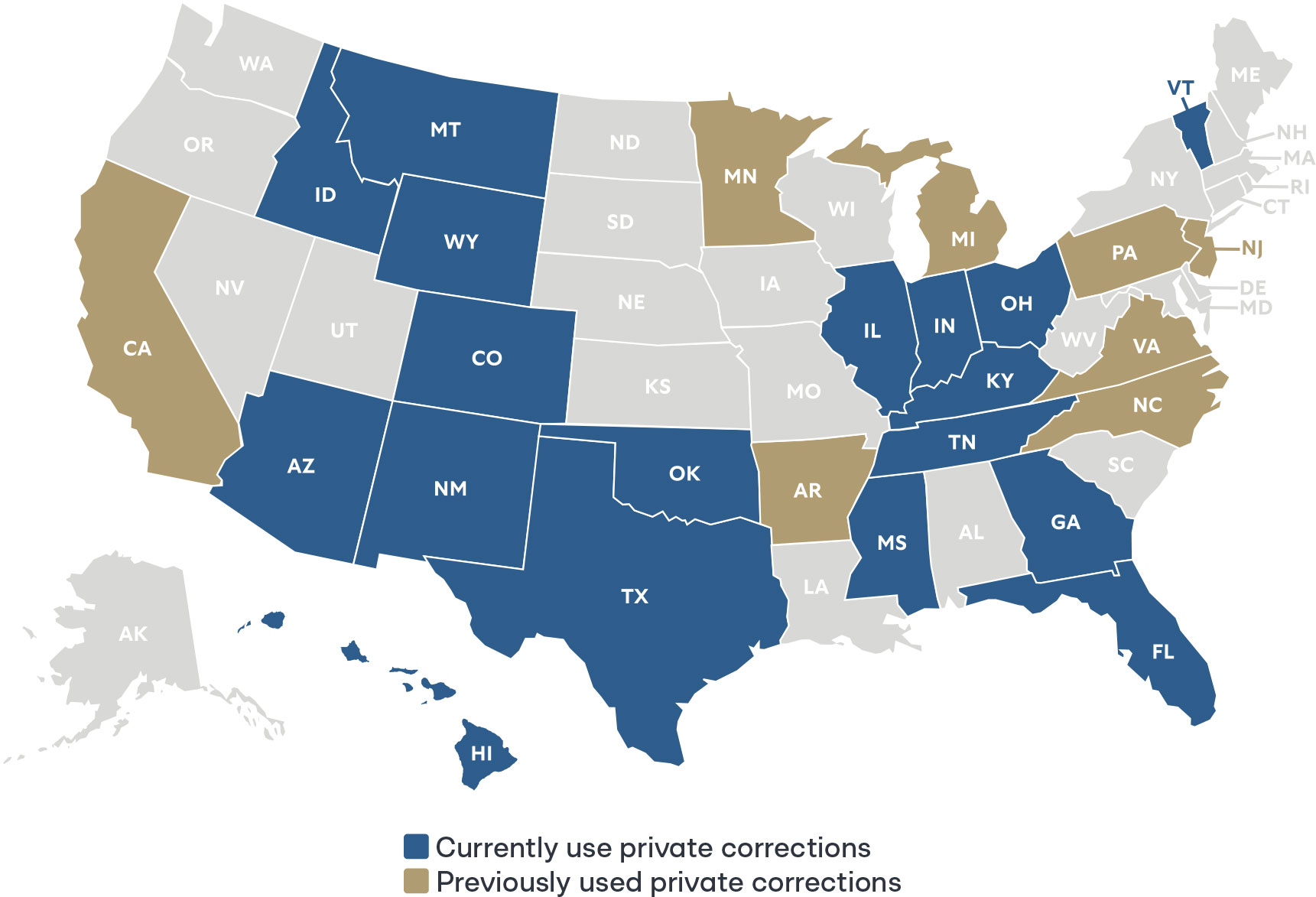

In 1999, there were 12 for-profit firms managing adult corrections, though this has significantly dwindled as a result of acquisitions and mergers.8 This has created an oligopoly that is difficult to break because of a barrier preventing new entrants to the field of corrections management: incumbent protections found in state procurement laws that require demonstrable experience from the entity itself. In a review of procurement law, five of the 18 statesi that use private corrections—Arizona,9 Kentucky,10 Mississippi,11 Ohio,12 and Tennessee13—have clear incumbent protections preventing start-ups from submitting a bid. These clauses, to which incumbent companies such as CoreCivic and The GEO Group devote significant lobbyist resources to protect, prevent new market entrants beyond the existing oligopoly of companies.

In theory, these laws are meant to limit the number of proposals received by only allowing those entities with a history of prison management to compete for a contract. In practice, however, these incumbent clauses prohibit new entities from submitting a proposal even if they have corrections experts on staff with the experience required to operate the prison. An example is Social Purpose Corrections, a non-profit prison operator founded by a former warden who seeks to compete against private prisons without the moral complications of profit motives.14 Because Social Purpose Corrections is a new entrant that has not yet operated a facility—even though its founder and staff have—the non-profit may not compete for prison contracts in certain states. Any new entrant attempting to utilize the private sector advantage of competition and innovation to improve correctional outcomes or costs is unable to do so as a result of these state laws.

Contradictory incentives can be realigned to support socially beneficial outcomes and the anti-competitive policies that currently define the industry can be dismantled to allow new, innovative companies to push the private corrections market to work as it should.

i As of writing, Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Montana, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, and Wyoming all use private prisons to house inmates in the respective state’s custody. Some of these states, such as Idaho, Hawaii, Vermont, and Wyoming do not have private prisons within their state but send prisoners to privately operated facilities in other states.

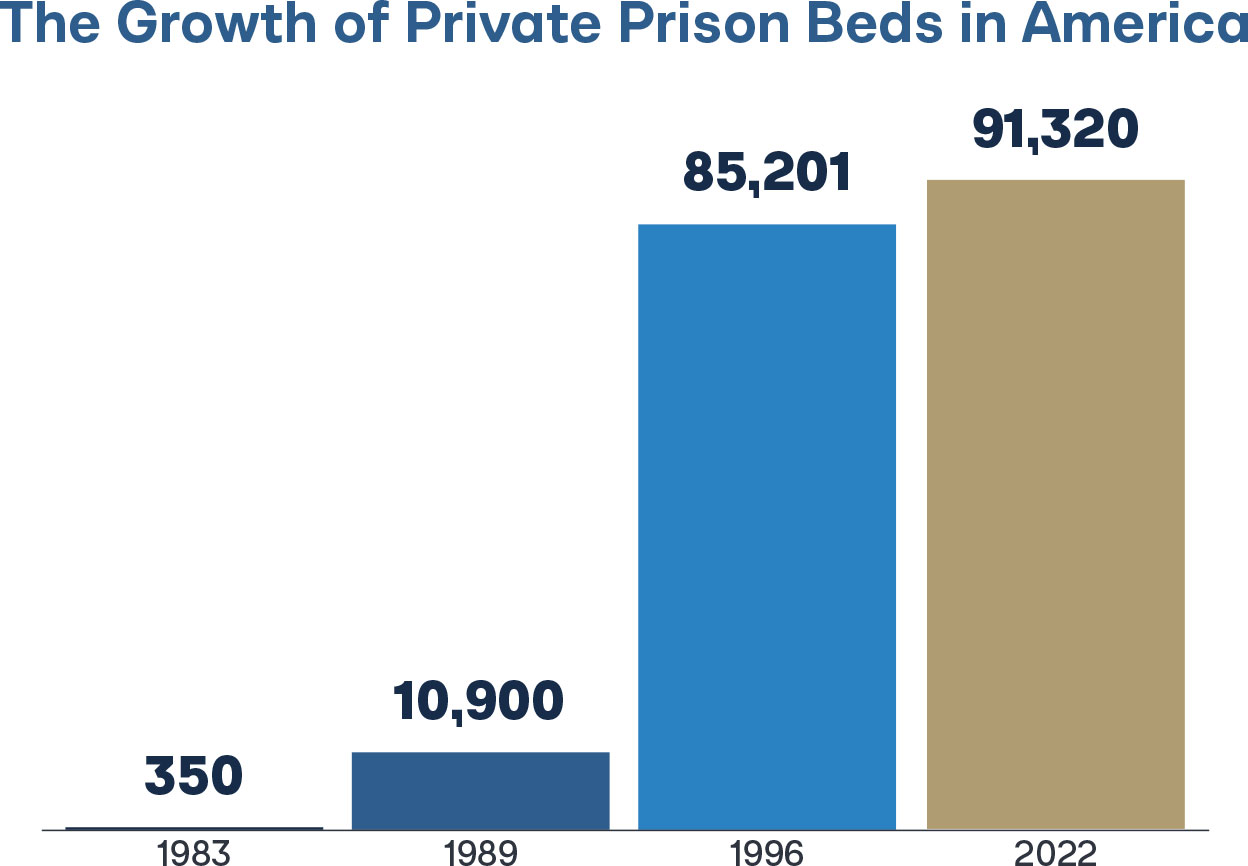

History of Private Corrections

There is some disagreement around when the use of prison privatization officially began in the United States. However, the Office of Justice Programs acknowledges the establishment of Corrections Corporation of America in 1983 as the official beginning of the private prison industry.15 By the end of the decade, there were approximately 10,900 private prison beds, which continued to grow into the 1990s as federal and state governments were facing budgetary shortfalls and private prison corporations had established legitimacy with the departments. By 1996, the inmate population in private prisons had risen to 85,201; as of 2022, the population is 91,320.16 States account for the majority of private prison use (approximately 85 percent) due to reduced overhead costs, mainly construction and labor, and the ability to expand prison bed space rapidly.17

Three main companies dominate today’s private prison industry: CoreCivic, a Tennessee-based company with over 10,000 employees managing 72 facilities and earning nearly $2 billion in revenue;18 Management & Training Corporation, a privately held company with 15 state prisons in the country and over 8,000 employees;19 and The GEO Group with more than 15,000 employees and 64 correctional facilities in the United States, grossing nearly $1.5 billion in revenue.20

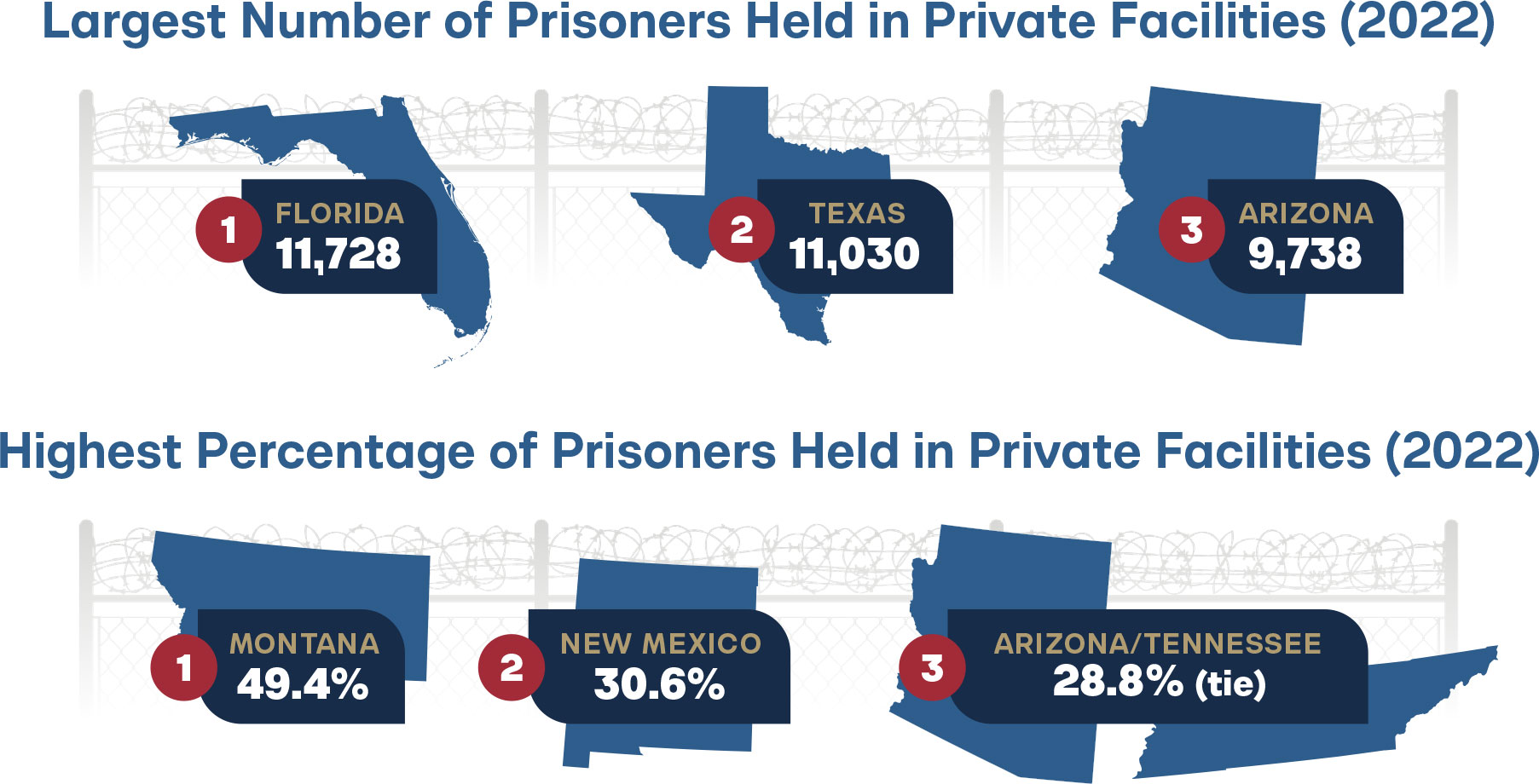

When looking at private prison data, one must consider not only the number of private prisons but also the proportion of inmates they house. Florida has the largest number of private prisons per state, with seven facilities, for example, but they house only 13.9 percent of Florida’s inmate population.21 Arizona, on the other hand, has six private prisons, but they hold 28.8 percent of the state’s inmate population. Half of Montana’s prison population is housed in just two private facilities, making it the state with the highest percentage of its committed population in private facilities, followed by New Mexico at 30.6 percent and a tie for third place between Arizona and Tennessee, each with 28.8 percent of their respective prison populations in private facilities.22 Florida has the largest number of prisoners held in private facilities with 11,728, followed by Texas with 11,030, and Arizona with 9,738.23 Some states don’t have any private prisons yet send prisoners to private facilities out of state. An example of this is Vermont, which houses 8.1 percent of its incarcerated population in a private prison in Mississippi.24

Current Performance and Research on Cost

Researchers have yet to come to a consensus on whether private prisons are more efficient in creating better outcomes for prisoners or reducing costs to the public. A literature review of prison privatization studies found a lack of rigorous research on the topic.25 Other research found small amounts of cost savings; one study found a 2.2 percent decrease in costs associated with privatization.26 Others, such as a meta-analytic review of 24 studies, found no statistical difference in cost when using a regression equation to control for the number of inmates, security level, and age of the facility.27

In one review of 28 cost-comparison studies, “virtually all” found that private confinement costs less than public confinement by an average of five to 15 percent.28 However, it should be noted that this review was published by the Reason Public Policy Institute (affiliated with the Reason Foundation), which has received donations from private prison companies, such as The GEO Group and CoreCivic.29

The benefits that were promised did not come to fruition, according to some researchers.30 Past research has found that total, inflation-adjusted costs were higher in private prisons than in public prisons, at a rate of 1.5 percent higher over 25 years and three percent higher over 40 years.31

Others found that the introduction of private prisons increases the state’s recidivism rate by 6.5 percent over three years and 8.6 percent over six to nine years, suggesting the long-term costs are not worth the short-term savings.32 This finding of higher recidivism in private prisons was further supported by a targeted study of inmates released from Minnesota’s private and public institutions which found that private prisons presented a greater propensity for recidivism across 20 different regression models.33

Further, the Office of Justice Programs found that instead of the purported 20 percent reduction in overall costs, private prisons experienced an average of one percent in cost savings.34 Additionally, since 2010, there has been a 280 percent increase in the number of inmates aged 55 and older,35 and institutions are spending approximately five times more to care for inmates in this age bracket than for inmates 49 years of age and younger, as of 2015.36 This cost is expected to increase as the prison population ages, leaving the cost savings further in question given that private prisons often cap the amount of funds that they will pay for medical costs per inmate and anything above that cap will be paid for by the state.

Private prison guards are 49 percent more likely to experience a violent incident, and inmate-on-inmate violence is 65 percent more prevalent in private prisons when compared to government-run prisons.37 Some of this may be attributable to the recruitment and training of employees seeing as the public sector requires 58 more training service hours for correctional officers than their private counterparts, and prisons in the private sector experience a turnover rate that is three times higher—15 percent for public versus 43 percent for private—with the private sector paying approximately 22-25 percent less in annual salary and benefits than the public sector.38 Given that the private sector has 28 percent of the inmate population in specialized treatment such as DUI programming versus the public sector having 14 percent, it is necessary to explore the potential internal, employee-based causes of heightened violence in prisons and increased recidivism after initial release given the impact that correctional officers can have on the mentoring and success of the inmates.39

Pathways to Reform

There are several potential pathways to reforming private prisons. First and most extreme is the abolitionist movement which argues that all prisons are morally reprehensible and reconciliation is a more ethical and proper response to crime. In the drive to do away with prisons, abolitionists cite the conditions of prisons and jails they believe to be inhumane. These conditions are partially due to the criminal justice system’s absorption of social welfare work.40 While there is research showing that harsher and increased punishments do not reduce crime, abolitionists overlook the fact that the majority of offenders who move through the criminal justice system are placed on probation or some form of community supervision as opposed to prison or jail. Those who are in prison, moreover, are far more likely to be there as a result of a violent crime than any other reason, and even those in prison for a supposedly non-violent crime are likely to have committed a violent crime before or demonstrate risk factors making them more likely to commit one in the future.41 For example, a 2021 report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics noted that people released from prison after being convicted of a drug-related crime are more likely to be re-arrested for a violent offense than people released after being convicted of a homicide or sexual assault.42 This does not mean that we should not examine who and how we incarcerate, but the assertion that offenders who pose the highest risk to society could be safely supervised in the community is illogical and dangerously incorrect.

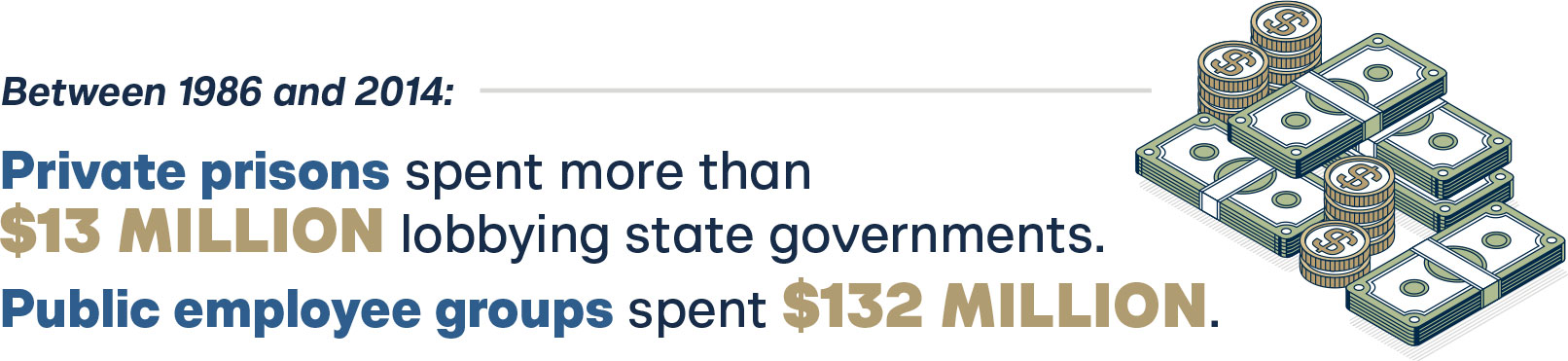

A less extreme cohort of criminal justice reform advocates only abolishing private prisons. This cohort misunderstands that much of the criticism surrounding private prisons is as applicable to public prisons–if not moreso. Public prisons face the same perverse incentives to fill their facilities with prisoners as private prisons, as the loss of a prison in a district would mean the loss of jobs. Job loss can mean the loss of a vote to the politician in charge, as these public prisons are often the main generator of economic activity in predominantly rural areas.43 Public prisons lobby just as private prisons do–between 1986 and 2014, private prisons spent more than $13 million lobbying state governments; public employee groups spent $132 million in the same period.44

Further, eliminating private prisons would close an avenue for meaningful prison reform. While it’s true that, up to this point, private prisons have not delivered on their promises of meaningful innovation, the private sector will always be nimbler than the public sector in any field. With the correct incentives and true market competition, there is good reason to believe that private corrections can achieve better outcomes for inmates through quicker adoption of best practices and increased allowance for innovation in response to pressures and incentives from which the public sector is mostly shielded. Whether one agrees with the concept of private prisons, it is indisputable that for many states, private corrections is here to stay. The correct incentives can make private prisons into a force for good.

Prison reformers represent a balanced wing of the broader movement to improve prisons. By recognizing the need for and legitimacy of prisons while arguing that prisons have room for meaningful improvement, prison reformers find broad support among the American public. What is missing among this group is a pathway to achieve comprehensive reform. The public largely desires that prisons better equip prisoners to desist from crime yet has very little understanding of how to do so. Individuals, such as innovative directors of corrections, are hamstrung by the bureaucratic and sluggish realities of reforming public agencies. At the same time, outside reform groups and academics that put forth piecemeal reforms lack the power to impact prison operations directly.

Finally, there is a segment of elected representatives and broad swaths of the public who want tougher, more expansive incarceration. Remnants of the “tough on crime” movement of the nineties, this group primarily sees prisons as a tool to prevent more crimes from being committed. There is certainly some truth to prisons being a tool to prevent further harm to communities by removing those likely to recidivate for a time. Yet even this group should value the effective use of public funds. In other words: if prisoners are already incarcerated, prisons should make good use of that time.

Policy Proposal: Dismantle Anti-Competitive Policies

The first step in private prison reform should be the repeal of anti-competitive policies. Capitalizing on the industry’s promise of efficiency requires true competition, so new entrants must be allowed to challenge the stagnant incumbents and reenergize the fight for state contracts.

As noted previously, several states have procurement restrictions in their respective state codes. Broadly, there exist two levels of procurement restriction: a category which we will call the “qualifications” requirement and a category which we will call the “demonstrated history” requirement.

The “qualifications” requirement essentially requires an entity proposing to manage a correctional facility to show that it has the qualifications and experience to provide the services called for in the contract. Colorado,45 Florida,46 Idaho,47 Montana,48 Oklahoma,49 and Texas50 all have this type of requirement. This type of restriction doesn’t necessarily inhibit competition among private entities seeking to bid on a correctional facility management contract—it’s unlikely that a state would ever award such a contract to an entity without any demonstrated qualifications, therefore requiring such qualifications as a prerequisite to submission is unlikely to inhibit true competition.

The “demonstrated history” found in Arizona,51 Kentucky,52 Mississippi,53 Ohio,54 and Tennessee55 is far more concerning. This restriction requires the proposing entity to have a demonstrated history of successful operation and management of other correctional facilities, creating a true “chicken-and-egg” paradox. If a group of experienced corrections experts leave one company and decide to create a new, competing entity, those experts are disallowed from submitting competing bids simply because the novel entity they have formed lacks demonstrable experience in managing prisons.

Yet, if the entrant is clearly qualified and unable to bid on contracts, the entrant will never be eligible for a contract. Thus, the incumbents remain artificially insulated from any new, competing entity.

This type of procurement restriction has allowed the big three corrections management companies, CoreCivic, The GEO Group, and MTC, to remain untouchable for decades. While these three companies technically compete against each other, the cartel-esque protection is mutually beneficial. All three companies rely on the same unaccountable contract structures, offer the same sorts of programming, and rely on the same business model of ensuring beds are filled for the lowest possible cost.

If states repealed these contract protections, new entrants such as the non-profit Social Purpose Corrections could force these incumbents to improve. They would need to become nimbler, focus more on the outcomes of their residents, and drive costs lower over the long term with reduced recidivism.

Policy Proposal: Outcomes-Based Contracting

The second policy addresses one of the most fundamental errors in the private corrections space: the reliance on per-diem occupancy or guaranteed, minimum-bed contracts. These contract structures ensure providers receive more income from the taxpayer the fuller their facilities are and, in turn, deliver greater shareholder distributions the lower they can push costs. John Pfaff writes about the lack of accountability and aligned incentives with per-diem contract structures in his essay “The Incentives of Private Prisons” and recommends incentive contracts instead.

The introduction of outcomes-based contracting has the potential to revolutionize American corrections. At its core, outcomes-based contracting means measuring achieved outcomes such as reduced recidivism and increased job placement, rewarding contractors who can better those outcomes, and penalizing those who worsen them. Under an outcomes-based contract, the incentive of the private entity is entirely aligned with that of the state–to confine the offenders safely and rehabilitate them effectively.

One example of an outcomes-based contract would guarantee a minimum amount to the entity, require marginal improvements to earn the “full” contract amount, and provide a bonus schedule for improvements beyond the required minimums. This contracting structure is in line with research on how to incentivize improved outcomes from correctional providers. Bushnell (2019) argues that “recidivism incentives should be bonuses rather than penalties,” and that “private prison contracts should be structured so that operators cannot make their margins without the recidivism bonuses.”56 This is similar to Cullen’s (2014) argument in American Prison, where he suggests that all “profit” be tied to meeting performance incentives, including staff retention.57

This is not a new concept; performance-based contracts are already used for prisons in Australia and New Zealand. In Ravenhall, Australia, a facility run by The GEO Group received a $2 million bonus for achieving a lower recidivism rate in 2019.58 Serco operates Auckland South Correctional Facility in New Zealand with a performance-based contract that includes incentive payments for reduced recidivism and penalties for operational failures. Performance is based on six key performance indicators (KPIs) related to serious operational failures, 36 KPIs related to reducing security issues, and 16 KPIs related to long-term social outcomes. Under this contract, Serco was able to reduce rates of reoffending by 12.52 percent for the indigenous population and 36.56 percent for the general population as compared to the publicly operated prisons in New Zealand. For this success, Serco received a $1.1 million bonus.59

In 2024, Arizonan House Bill 2783 attempted to introduce performance-based contracts in the U.S. with one standardized contract structure for all private providers.60 Under this proposed structure, any contract to provide correctional services would be split into a base payment and a performance incentive payment, collectively called the base achievement contract (BAC). The base payment would be guaranteed and represents 90 percent of the BAC. To receive the remaining 10 percent–the performance incentive payment–the entity would be required to reduce the return-to-prison rate–or recidivism rate–by five percent and increase the job placement rate by five percent. Both metrics would be compared to the baseline rates as achieved by the state’s department of corrections over the previous few years (collectively, the “base achievement rate”). If the entity achieves five percent improvements in both measures, the entity receives the entirety of the remaining 10 percent of the BAC. However, if the entity only achieves the five percent reduction in the return to prison rate, the entity receives 60 percent of the performance incentive payment (therefore, 96 percent of the total BAC). The inverse is true of the job placement rate at 40 percent of the performance incentive payment.

The bill went beyond that, making the entity eligible for bonus payments to encourage further improvements beyond the required minimums. For each percentage point improvement per metric that exceeds the base achievement rate, the bonus shall equal one percent of that metric’s value of the BAC’s performance incentive payment. The maximum earning is 120 percent of the BAC.

For example, assume a state contracted with a private entity to manage a correctional facility at a rate of $36.5 million per year, equivalent to a $100 per-diem contract for a fully occupied 1,000-bed facility. The entity is therefore guaranteed $32,850,000 in the base payment and, if the entity achieves the five percent improvements per metric under the base achievement rate, an additional $3,650,000 in a performance incentive payment.

The income would increase significantly if the entity achieved a 10 percentage-point improvement in each metric. The entity earns the guaranteed base payment, the performance incentive payment, and an additional $21,900 per percentage-point improvement in the return to prison rate and $14,600 per percentage-point improvement in the job placement rate. This results in a total contract amount of $36,682,500. This includes the base achievement contract and a $182,500 bonus payment for reducing recidivism and increasing job placement.

Conclusion

Prisons, whether public or private, vary widely in quality of confinement and care. This need not be the case. Experiences within the United States and abroad show that both systems have good and bad aspects but that positive change can occur for inmate outcomes by capitalizing on the strengths of each of the systems. By focusing on what each of the systems does well, the ultimate goal of improving recidivism and public safety may be realized. Recent history shows that public institutions are very good at housing, protecting the individual constitutional rights of the accused, and are more aligned with public safety over profit. However, private industry has picked up where many public institutions have fallen short; physical and mental healthcare, post-confinement housing, job placement, etc. Given this, the future of prisons may not lie in a binary response to prison management, but a collaborative, free-market-based partnership between public and private institutions. This ensures that the most effective, data-informed practices, based on a comprehensive risk/needs assessment, are achieved to provide inmate rehabilitation and ensure public safety. Though public prisons face a very different set of incentives and forces, states that use private corrections services can adopt the two easily instituted policy solutions recommended in this paper and revitalize competition among managing entities.61 This would ensure incentives are aligned with the public’s expectation of outcomes.

Appendix A: Overview of Private Corrections

Appendix B: Private Corrections Procurement Restrictions