Unlocking Pharmacist Innovation:

2025 Policy Strategies for Full Practice Authority

Executive Summary

The United States faces an urgent shortage of primary care providers, and pharmacists are uniquely positioned to close this gap and expand access to care nationwide. Despite their extensive education, training, and clinical expertise, pharmacists remain constrained by outdated legislative and regulatory barriers that prevent them from practicing to the full extent of their profession.

Granting pharmacists full practice authority under a standard of care framework would unlock their potential to expand access to preventative health services, improve the management of common illnesses and chronic diseases, and streamline testing and treatment for a wide range of conditions.

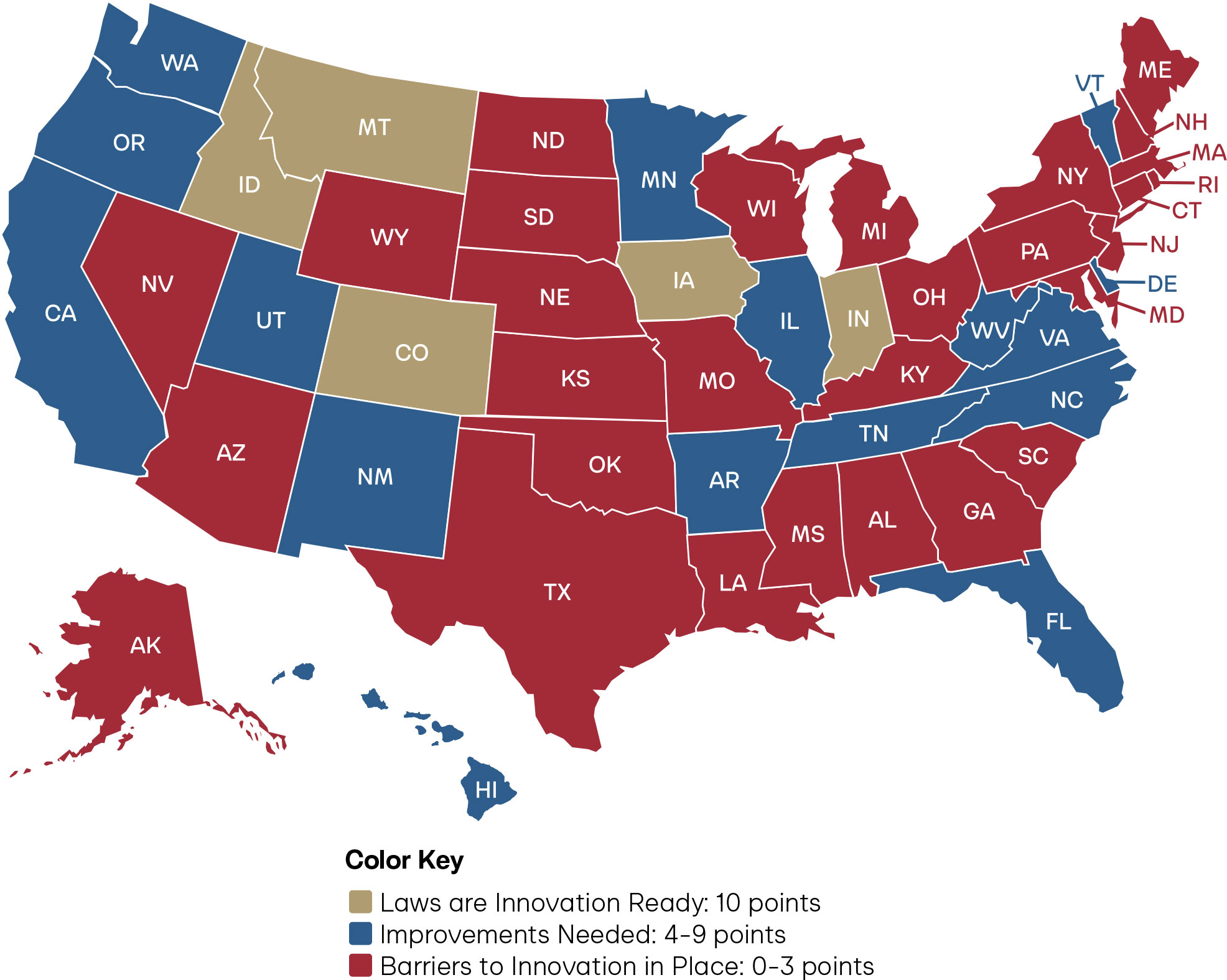

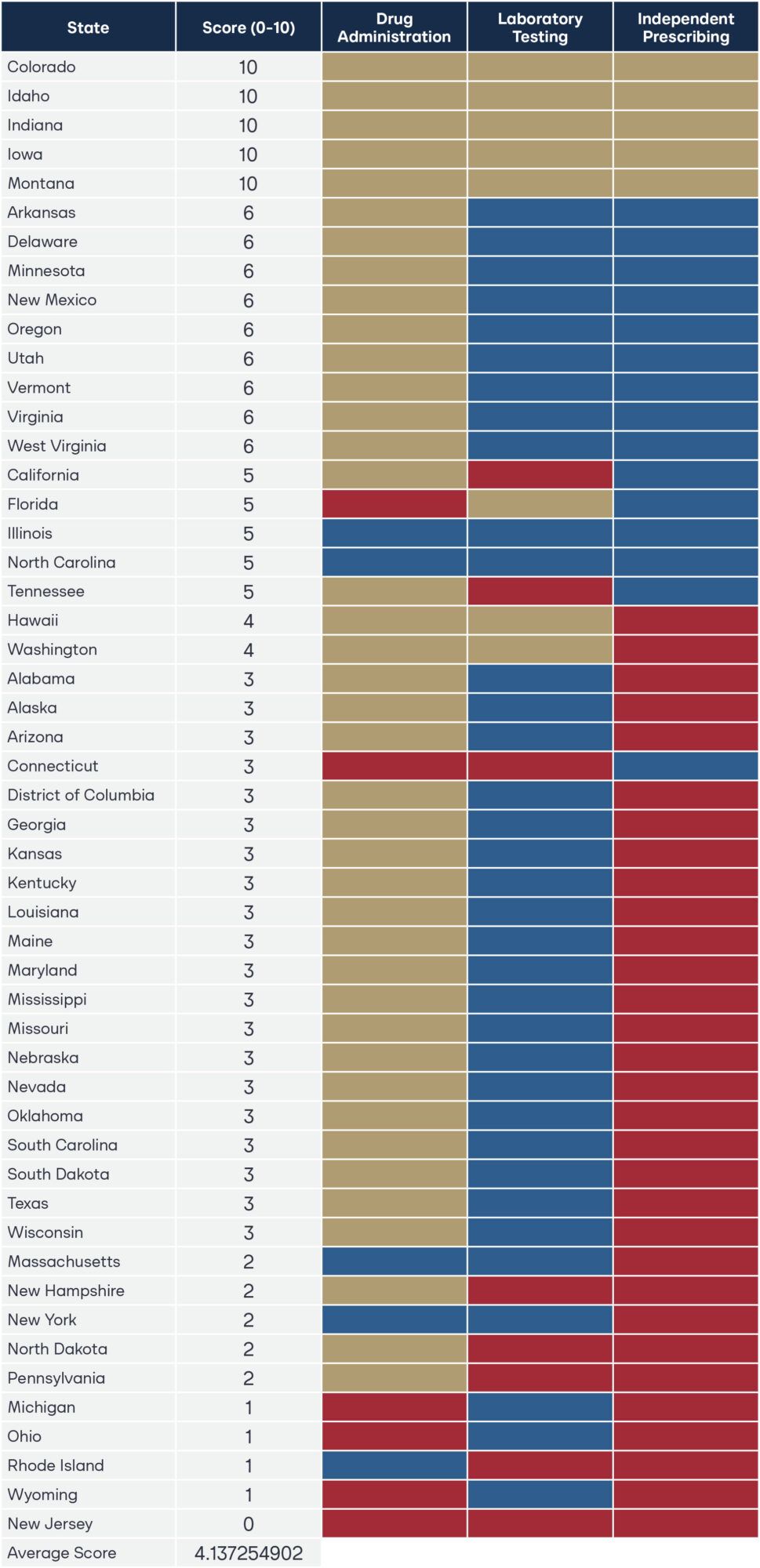

This research establishes a legislative taxonomy that scores every state on pharmacist authority in three essential clinical patient service domains: drug administration, laboratory testing, and independent prescribing. Using statutory and regulatory analysis, states were evaluated on a 10-point scale. The results reveal a national average score of just 4.1, underscoring the untapped potential of pharmacists to strengthen primary care access.

Five states—Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Montana, and Colorado—earned a perfect score, demonstrating that full pharmacist practice authority is both practical and achievable. These states provide a clear roadmap for policymakers across the country seeking to modernize laws, reduce barriers to care, and empower pharmacists to practice at the top of their education, training, and experience. The appendix details specific statutory and regulatory provisions in each state that must be addressed to achieve full pharmacist practice authority. Policymakers committed to expanding healthcare access should look to the findings of this research as a guide for targeted, high-impact reform for rural America.

Background

Physician Shortages and How Pharmacists Can Help

About one-in-three Americans do not have a primary healthcare provider, and the rest often experience long wait times before an appointment with a burnt-out physician, or simply forgo care altogether.1–2 By 2034, the United States is projected to have a shortage of up to 124,000 physicians, according to data from the Association of American Medical Colleges.3 Yet the scarcity will not be felt equally in each state. Seventy-six million Americans live in a primary care Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA), and two-thirds of all primary care HPSAs are in rural areas.4–5

Complicating the situation, as hospital systems consolidate, rural providers tend to be absorbed into larger corporate health systems, further driving healthcare resources to urban areas and exacerbating shortages in rural communities.6 The compounding challenges uniquely position pharmacists to address the physician deficit.

Further, patients residing in rural HPSAs disproportionately tend to be elderly, have more trouble accessing care, and need it more often. Pharmacists can fill this gap, improve the quality of life for these vulnerable patients, and possibly even extend it.7

While the shortage of physicians and primary care providers worsens, the United States healthcare system fails to leverage the 330,000 doctorate-trained (PharmD) pharmacists who are qualified and ready to provide many medical services to patients.8 Pharmacists can address primary care shortages, diagnose and manage many chronic diseases, treat minor ailments, reduce unnecessary emergency visits, and improve health outcomes. Beyond their qualifications, patients rank pharmacists as trusted healthcare providers in terms of honesty and high ethical standards.9 Weekend and evening hours make pharmacists one of the most accessible healthcare providers, with local pharmacies serving as a central healthcare pillar.

Ninety percent of Americans live within five miles of a pharmacy, with urban Americans residing on average within a two-mile radius of pharmacy services.10 By allowing pharmacists full practice authority, primary care will be delivered where it is needed most: rural America. Physician shortages can be safely and effectively alleviated by enabling pharmacists to utilize their full training and experience.

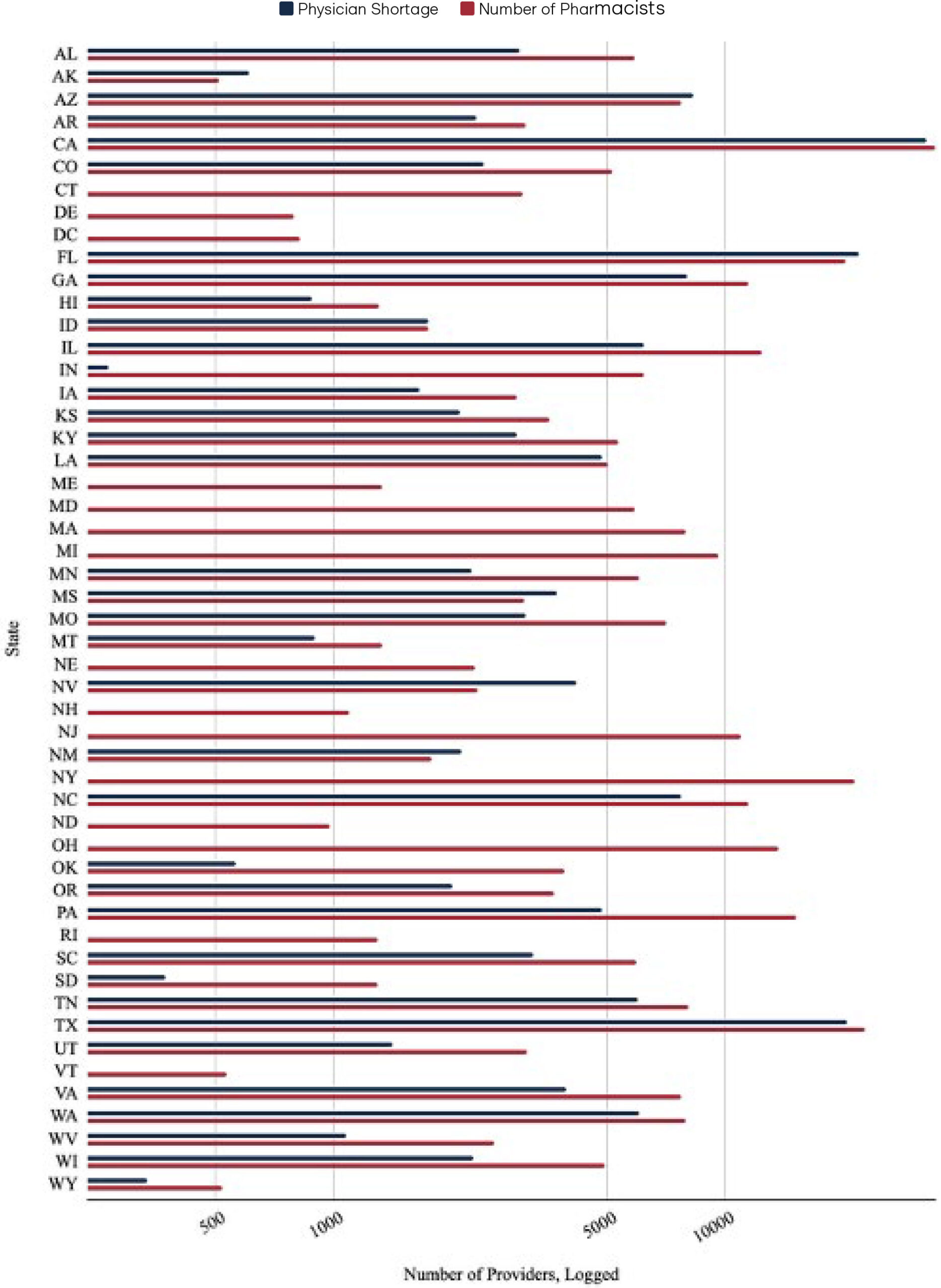

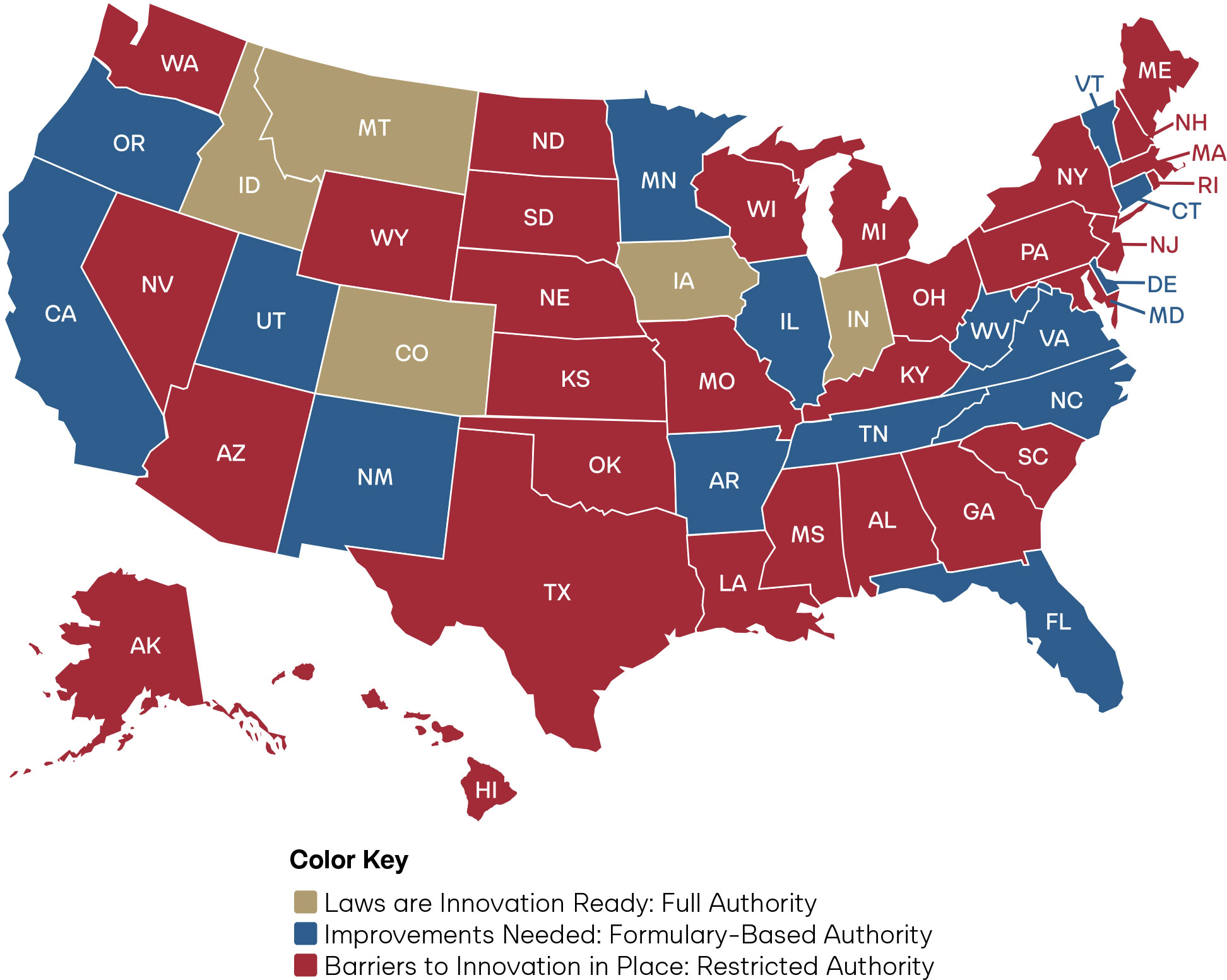

Figure 1. Projected Physician Shortages and Number of Pharmacists, By State

Figure 1 demonstrates the particular impact that pharmacist full practice authority could have on addressing upcoming physician shortages. This chart takes the projected physician shortage data from a 2020 study that estimated the shortage of physicians in each state and contrasts it with the number of pharmacists employed in each state as of May 2024, as reported by the semi-annual Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS) data by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).11–12 For ease of readability and to effectively account for significant differences in population, the x-axis was transformed using a logarithmic scale. The raw data used to create Figure 1 can be found in the appendix.

Notably, OEWS data only captures pharmacist employment in the physical location of the primary establishment where the pharmacist works within a state.13 It does not include the number of pharmacists licensed and practicing by state; rather, it only includes employment. This means the figures represent the number of pharmacist positions in a given state, rather than the total number of individuals licensed or potentially practicing across multiple states. Consequently, while the pharmacist employment data captures the majority of pharmacists, it may not fully capture pharmacists who practice in multiple states or via telehealth. Thus, the number of practicing pharmacists in each state represented in the chart above is a conservative estimate.

Some states do not include physician shortage estimates because not all states are projected to have physician shortages. Regardless, unlocking pharmacists’ full practice authority even in states without a projected deficit is crucial. By diversifying the existing healthcare provider workforce, states that empower pharmacists can improve healthcare accessibility, increase efficiency across the healthcare system, and foster a more responsive and competitive healthcare environment.

Safety and Education

Education and training standards for pharmacists are standardized across all states. Pharmacists must graduate from an accredited Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) program and demonstrate clinical competence by passing the North American Licensure Examination (NAPLEX).14 The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), a national agency recognized by the U.S. Department of Education, ensures the educational standards of these professional degree programs.15 ACPE curriculum standards include: applying clinical laboratory data; prescribing, preparing, distributing, dispensing, and administering medications; patient assessment; and pharmacotherapy (including self-care version).16 Following four years of undergraduate, pharmacists train another 1,740 hours of clinical patient care to achieve their doctorate. This is more than twice the 750 clinical patient hours that Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs) must complete, and APRNs have full practice authority in more than 30 states.17

Pharmacists in jurisdictions across the United Kingdom, Portugal, the United Arab Emirates, New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and in some jurisdictions in the United States have successfully diagnosed and independently prescribed for decades. Peer-reviewed literature supports the patient demand, acceptance, and safety profile, and there is little evidence to suggest reduced quality or legitimate patient safety concerns.18

Multiple randomized controlled trials demonstrated that pharmacist care is significantly superior to physician care when independently prescribing and managing cardiovascular diseases (CVD) like hypertension, hyperlipidemia, tobacco cessation, and diabetes.19, 20, 21, 22, 23 A Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA) article concluded that if pharmacists were to prescribe blood pressure control in the United States with a 50 percent intervention uptake, it would save $1.137 trillion and extend 30.2 million years of life over 30 years.24 Patients could save an average of $277.78 per visit compared to urgent care and emergency care visits when treated by local pharmacists for minor ailments.25 Another $4 billion alone can be saved annually in emergency visit costs for urinary tract infections (UTI).26 Research demonstrates that pharmacists can treat uncomplicated UTIs effectively, safely, and with high patient satisfaction.27 The significant economic impact of UTIs is only one of 30 minor ailments that pharmacists are trained to treat.28, 29, 30

Full Practice Authority Grounded in a Standard of Care Framework

American physicians practice under a broad framework known as the community standard of care. This standard serves as the regulatory benchmark for evaluating whether a healthcare provider has acted as a reasonable and prudent professional of similar training would in comparable circumstances. Under this framework, providers may perform any act not expressly prohibited by federal or state law, provided it is consistent with their education, training, experience, and clinical competence. By anchoring practice in professional judgment rather than rigid regulation, the standard of care promotes innovation while protecting patients and ensuring providers are not unnecessarily constrained in delivering care.

Unlike physicians, who practice under the flexible framework of the community standard of care, pharmacists are often bound by rigid, prescriptive regulations that leave little room for professional judgment. These bright-line rules frequently outnumber physician regulations in volume, by as much as 300 percent, creating a system where pharmacists are prevented from fully utilizing their education and training.31 As a result, patients are denied access to the higher level of care pharmacists are prepared to provide.

Idaho offers a clear example of reform. In 2017, the state shifted from a rule-heavy approach to a standard of care model, cutting pharmacy regulations from 125 pages down to just 15. This streamlining has empowered pharmacists to innovate in patient care, expanding their ability to diagnose, prescribe, and manage treatment while still operating within the boundaries of their education, training, and clinical competence. At the same time, Idaho preserved strong back-end accountability measures, ensuring that pharmacists remain fully accountable through professional and disciplinary oversight under the standard of care framework.32

Achieving full practice authority is not merely an expansion of duties or scope creep. Instead, it is the explicit removal of legitimate and unfounded regulatory barriers that obstruct pharmacists from realizing their full practice potential and prevent patients from the best possible therapeutic outcomes and direct primary care access.

Full practice authority empowers pharmacists with the independent authority to perform a full range of patient services, including prescribing, administering, and managing medications, without being constrained by outdated legislation or restrictive oversight.33–34 Dr. Ross Tsuyuki and colleagues define independent authority as “all proactive and comprehensive interventions that prevent or manage illness and are within an individual’s competency to perform independently.” They advocate abandoning terms like “expanded” or “enhanced” scope. Following the American Association of Nurse Practitioners’ (AANP) successful full practice authority model, nurse practitioners could implement a standard of care framework, agree on a scope of practice decision-making framework, and adopt broad definitions for the practice.35 Additionally, there are reduced or restrictive practice states that have limitations on independent authority functionality or require physician oversight through collaborative practice agreements or supervision ratios.36 Rather than creating a new regulatory method or prescriptive bright-line approach like pharmacy, the nursing profession successfully replicates physicians’ success and broadly defines the practice of nursing to allow innovation and practice to the full extent of their education, training, and experience.

Previously, there has been a continuum of innovation in states’ scope of practice, with some positive developments in patient care and other poor concessions that should be opposed.37 For example, in 1979, Washington state permitted pharmacists to initiate therapy through population-based collaborative drug therapy agreements. Following the peer-reviewed literature and patient safety outcomes supporting Washington’s approach, 35 states passed their own restrictive patient-specific collaborative practice laws.38 Most of the time, these laws are unusable and unworkable in community pharmacy environments. In 2021, Adams and Weaver argued that states must empower pharmacists to order and interpret lab tests, prescribe, adapt, and administer medications, and delegate tasks to support staff to implement the Pharmacists’ Patient Care Process fully.39

The failure to implement population-based collaborative practice across the states and the lessons learned about scope advancements from APRNs, physician assistants, psychologists, and optometrists prove the need to pursue independent practice models.40 However, a barrier to this process is the extensive regulatory burden faced by pharmacists. Among healthcare professionals, pharmacy is one of the most heavily regulated when accounting for restrictions and the overall word count of regulations.41 State and national medical associations utilize existing restrictions and collaborative practice laws as leverage against granting full practice authority for all healthcare professionals.42

Although collaborative practice agreements have long been the accepted norm, the delegated authority upon which they are based can be undelegated at any time. The only basis for the authority in the first place is the act of delegation. Full practice authority, by contrast, establishes a pharmacist’s professional autonomy based on their education, training, and experience, ensuring that the authority to provide care is a permanent and inherent right.

Under a standard of care regulatory model, pharmacists can perform any function for which they have the training, education, and experience. Unless explicitly prohibited by law, a pharmacist may proactively provide services to their full extent of clinical competence. To uphold this framework, state laws should ensure that pharmacists can have full practice authority in three core clinical areas: drug administration, laboratory testing, and independent prescribing.

Methodology

For this research, a legislative and regulatory taxonomy measures the extent of pharmacist full practice authority across the states. This is used to identify the relevant state statutes and administrative regulatory code in the areas of drug administration, laboratory testing, and independent prescribing. To measure pharmacist independent practice authority across the country, each state receives a separate score in the three core clinical areas for a maximum score of 10 points.

I. Overall scoring framework

Each state receives a total score out of 10 points, with points allocated to the three core clinical functions.

- For drug administration, states may receive a maximum of 2 points.

- For laboratory testing, states may receive a maximum of 2 points.

- For independent prescribing, states may receive a maximum of 6 points.

II. Detailed scoring of the three core clinical functions.

For drug administration:

- 2 Points: Full Authority

- A pharmacist may administer any drug pursuant to a valid prescription, without restriction by drug class.

- 1 Point: Formulary-Based Authority

- A pharmacist may administer drugs from a formulary-based list, which includes more than three drug categories.

- 0 Points for Restricted Authority

- Pharmacist authority to administer drugs is restricted to immunizations, naloxone, and/or epinephrine categories only.

For laboratory testing:

- 2 Points: Full Authority

- A pharmacist may order and perform any laboratory test based on clinical judgment, including but not limited to: Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-waived, moderate, and high-complexity tests.

- 1 Point: CLIA-Waived Authority

- A pharmacist may order and perform any CLIA-waived test, without restriction to disease or condition.

- 0 Points: Restricted Authority (Narrow CLIA-Waived List)

- A pharmacist may order and perform only a specific list of CLIA-waived tests, limited by statute, rule, or protocol.

For independent prescribing:

- 6 points: Full Authority Grounded in a Standard of Care Model

- A pharmacist may diagnose and prescribe drugs or devices based on the community standard of care, without reliance on preapproved statewide protocols or formularies.

- 3 points: Formulary-Based Authority

- A pharmacist may prescribe from a formulary or statewide protocol-based list of more than five drug categories.

- 0 points: Restricted Authority

- A pharmacist may prescribe from a formulary or statewide protocol-based list of five or fewer drug categories or products, or a pharmacist may only prescribe through dependent models (e.g., collaborative practice agreements, standing orders, and physician protocols)

Data Exclusion

This survey deliberately excludes authority granted under Collaborative Practice Agreements, standing orders, or prescriber-dependent protocols. These models do not represent independent authority and are inherently dependent on the authorization of another licensed practitioner. While they may expand a pharmacist’s practical scope in specific cases, they are not included in the scoring because they do not reflect autonomous, statewide pharmacist practice rights. Where the Board of Pharmacy authorizes statewide orders and does not require a prescriber’s signature, they may be scored differently and have been evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

The analysis assumes the authority to order and perform CLIA-waived testing is permitted under federal law in the absence of an explicit state-level prohibition. However, it does not score or interpret potential federal limitations or conditions under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) program, nor does it account for U.S. Federal Drug Administration (FDA) or U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) guidance that may indirectly affect pharmacist practice. This is a state-based analysis; it does not override or interpret federal law applicability beyond recognizing the default permissive federal framework for CLIA-waived testing. The authors note the complexity of analyzing silence under the law, and recognize clinical laboratory oversight is often not a regulatory mechanism governed by the state Board of Pharmacy law and rule.

This analysis does not assess restrictions imposed by penal codes, criminal statutes, or other non-pharmacy-specific legal frameworks that may limit pharmacist authority to dispense, prescribe, or administer certain drug categories. For example, drugs such as mifepristone, misoprostol, methotrexate, puberty blockers, and cross-sex hormones may be subject to additional legal constraints outside the scope of the Board of Pharmacy statutes and regulations reviewed in this survey. These drug-specific limitations, while relevant, fall beyond the boundaries of this research’s focus on core pharmacy practice authority.

Additionally, the survey excludes any expanded authority granted under advanced pharmacist licensure designations, such as Advanced Practice Pharmacist (APP) or Clinical Pharmacist Practitioner (CPP) models. These designations were not considered in the scoring due to their low adoption and uptake rates, the substantial additional training and procedural barriers required for licensure, and their minimal impact on practicing pharmacist authority when compared to states that authorize any pharmacist to diagnose and prescribe independently. This approach aligns with previous research indicating that such advanced licensure pathways have limited practical utility in expanding pharmacist practice authority at scale.

Results

Figure 2: Overall Scores of Pharmacist Full Practice Authority Across the States

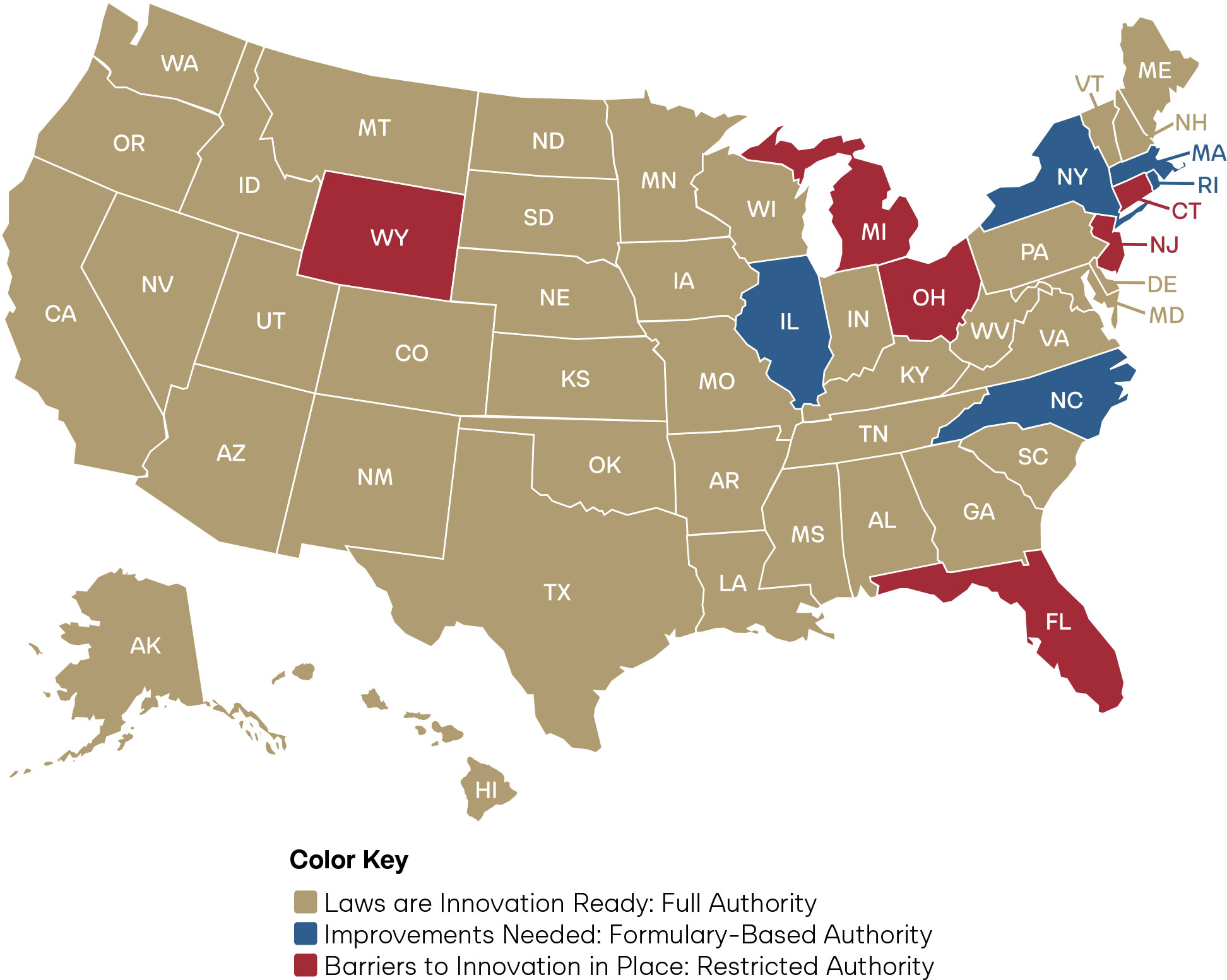

Figure 3: State Scores on Pharmacist Full Practice Authority for Drug Administration

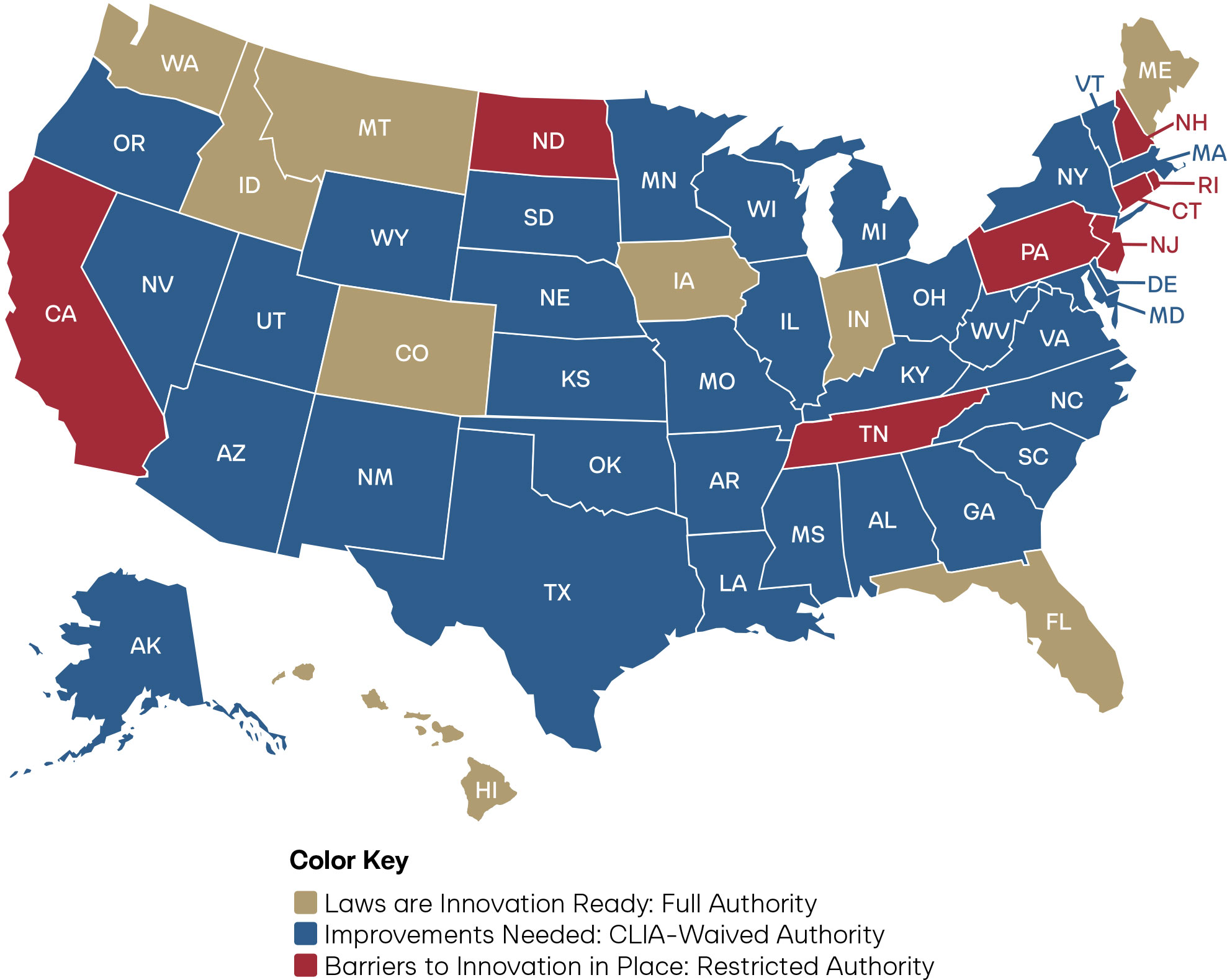

Figure 4: State Scores on Pharmacist Full Practice Authority for Laboratory Testing

Figure 5: State Scores on Pharmacist Full Practice Authority for Independent Prescribing

Analysis

This section analyzes the research results from the legislative taxonomy of full practice authority for pharmacists across the United States.

Overall

For pharmacists to practice at the full extent of their training, they must have independent authority across all three core clinical functions: drug administration, laboratory testing, and prescribing. These functions are interdependent, and true full practice authority cannot exist without all three operating in tandem. For example, the ability to perform laboratory testing for a urinary tract infection is of limited value if the pharmacist cannot also prescribe the necessary antibiotic. Likewise, a pharmacist who can prescribe for hypertension but lacks the authority to order laboratory tests to monitor renal function is unable to deliver safe, comprehensive chronic disease management.

As Figure 2 reflects, only five states have true full practice authority for pharmacists: Idaho, Iowa, Indiana, Montana, and Colorado. States desiring to further full practice authority in the states should refer to the figure below for guidance on which laws should be modernized.

Figure 6: State Policy Agenda for Pharmacist Full Practice Authority and Overall Scores

Drug Administration

Drug administration is the process of delivering a medication directly to a patient to achieve its therapeutic effect. As part of the Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) curriculum, pharmacists receive extensive training in administering medications across multiple routes, including injections, inhaled therapies, intranasal treatments, and topical, ocular, and otic applications.

Pharmacists are prepared to manage a broad range of drug categories within this scope. These include preventive therapies such as vaccines and travel-related medications; acute treatments like antibiotics or tuberculosis skin testing; and chronic disease management through long-acting antipsychotics or medications for substance use disorder, among others. This training equips pharmacists to provide safe, effective, and accessible care in diverse clinical settings.43 The vast majority of states allow pharmacists to prescribe any drug pursuant to a valid prescription, without restriction by drug class. Five states limit pharmacist drug administration authority to a formulary of three or more categories of drugs. Only Connecticut, Florida, Michigan, New Jersey, Ohio, and Wyoming restrict pharmacist drug administration to immunizations, naloxone, and/or epinephrine.

Of the core clinical patient care functions, pharmacist independence is seen most widely in drug administration. Still, to increase healthcare access, states should ensure pharmacists can administer all categories of drugs within their education, training, and experience.

Furthermore, a state should not restrict where drug administration can occur. For example, limiting pharmacist drug administration to hospitals, specific clinics, or only the licensed pharmacy space would be unduly restrictive. Many patients, especially those in rural or underserved urban areas, rely on community pharmacies as the most accessible healthcare providers. Allowing flexibility in where drug administration occurs will help pharmacists reach patients where they are.44 Expanded convenience coupled with full practice authority in drug administration will lead to increased medication adherence, immunizations, and access to time-sensitive medications.45, 46, 47

Laboratory Testing

In pharmacy practice, laboratory testing refers to the authority to order, perform, and interpret diagnostic tests that directly inform patient care.

As required by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education, the Doctor of Pharmacy curriculum requires application of clinical laboratory training in educational programs.48 Through the PharmD program, pharmacists receive extensive training that prepares them for ordering, performing, and interpreting laboratory testing.49 Despite society’s investment in the education of this branch of the healthcare workforce, just eight states allow pharmacists to order and perform any laboratory test, including CLIA-waived, moderate, and high-complexity tests, based on clinical judgment. Innovative states that have adopted an explicit standard of care regulatory framework, such as Alaska, Idaho, Iowa, and Washington State, also extend laboratory testing to the authority to order and interpret diagnostic imaging. States that are unclear on imaging authority can immediately solve the issue by adopting an explicit standard of care framework.

Additionally, 34 states and the District of Columbia limit pharmacists to Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-waived tests. CLIA-waived tests are laboratory tests designated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) as simple to perform, carrying minimal risk of error, and safe enough for use outside traditional laboratory settings, including at home. Common examples include pregnancy tests, rapid influenza assays, and blood glucose monitors. Constraining pharmacists to CLIA-waived tests severely limits their ability to provide all types of testing that they are trained to perform. California, Connecticut, New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Tennessee restrict pharmacists to a narrow list of tests they are allowed to perform.

Independent Prescribing

Independent prescribing means the authority of pharmacists to prescribe medications without direct supervision, delegation, or a collaborative practice agreement from an overseeing healthcare provider. Under a standard of care framework, the authority to prescribe drugs stems from state pharmacist licensure, practice act authority, and professional competency.

Prescriptive authority for pharmacists opens a pathway where patients can go to one location and see one provider to obtain a prescription and receive the needed medications. Simplifying the process of acquiring needed drugs increases access points throughout the nation, especially for individuals located in rural and underserved communities.50, 51, 52, 53

Of the three clinical patient care functions, independent prescribing is the cornerstone of pharmacist full practice authority, but paradoxically remains the most constrained nationwide. Only Colorado, Idaho, Iowa, and Montana can diagnose and prescribe based on a broad standard of care model. Indiana is unique in that its prescribing authority is anchored in the pharmacist’s independent authority to perform medication therapy management, which is defined in statute as “selecting, initiating, modifying, or administering medication therapy.” Fifteen states allow pharmacists to prescribe from a formulary or a statewide protocol for more than five categories of drugs. The vast majority of states require pharmacists to prescribe through a dependent model, such as a collaborative practice agreement, or for fewer than five drug categories.54

Conclusion

Restrictive statutes, prescriptive lists, and outdated laws prevent pharmacists from achieving full practice authority in the core clinical functions of drug administration, laboratory testing, and independent prescribing. Anchoring pharmacist full practice authority in a standard of care model grants states the ability to align laws with every pharmacist’s full capability, synchronize with progress in medical innovation, and ultimately reduce legislative burden. Given the projected physician shortages, the average state score of 4.1, the wide variance in scores across the states, and regional disparities highlighted in the maps, there is a compelling case for the urgent need for states to adopt an explicit standard of care regulatory framework allowing independent pharmacist full practice authority.

Appendix: Supporting Data, Regulatory Analysis, and Safety Evidence

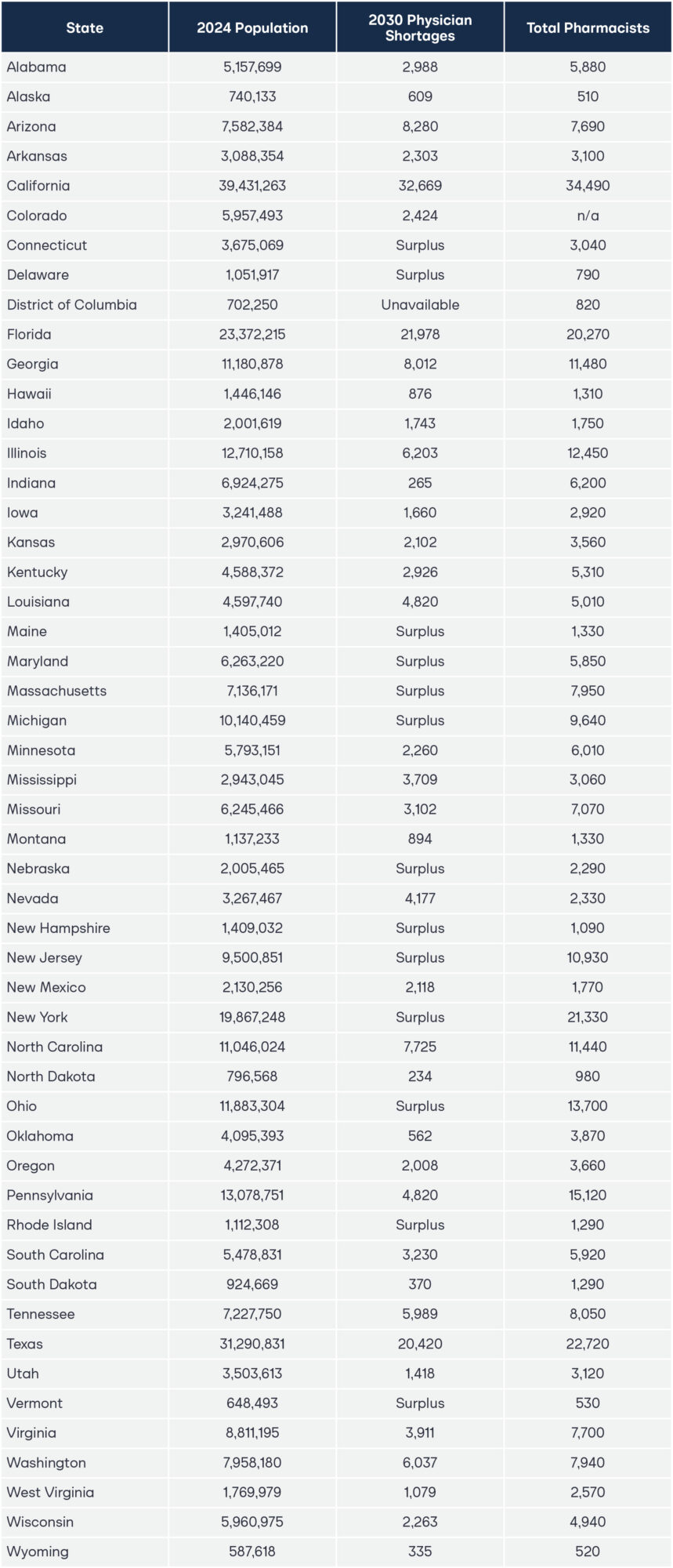

Appendix 1: State-Level Healthcare Workforce Data: Physician Shortage (2035) and Pharmacist Employment (2022)

Appendix 2: State-by-State Scoring Sheet Analysis of Pharmacist Full Practice Authority

The complete data set, including raw data of the state-by-state analysis tied to legislative statutes and administrative code, and additional metrics, is available via the online Google Sheet at: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1F2jPLI4pOAfYLL8rUhvzEiybfxsxl-I05MjDbqQTz-I/edit?usp=sharing

Appendix 3: Definitions of Drug Categories

A drug category is defined as a group of prescription medications that share a common clinical purpose, therapeutic intent, or regulatory treatment under pharmacy law or protocol. For scoring purposes, a drug category must:

- Represent a distinct area of therapeutic intervention (e.g., hormonal contraception, opioid antagonists, antiviral treatment), and

- Be authorized by law or rule in a manner that reflects independent initiation, distinct patient use case, or separate regulatory treatment.

- Pharmacist authorities to prescribe supportive or adjunctive treatments that are inextricably linked to a primary clinical function (e.g., epinephrine for immunization emergencies) are considered part of the same category as the primary therapy.

- However, treatments that differ in timing, indication, or public health purpose—such as HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) versus Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)—are scored as separate drug categories, even if pharmacologically similar.