Rejecting Housing First:

Why America’s Homelessness Strategy Failed and How to Fix It

Background

For decades, the U.S. federal government, through the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH), has dominated the country’s response to homelessness via their policy response known as Housing First. It has been an unmitigated disaster, yet in 2009, the Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing (HEARTH) Act astonishingly initiated an unprecedented expansion of Housing First.1

Unironically, academics, policy advocates, and policymakers have long hailed Housing First as a panacea, repeating the intellectually arrogant refrain, “We know how to solve homelessness.”2 Yet, America’s once-great city centers are proof that the opposite is true. The federal government and much of the public have been deceived by idealistic policy frameworks and researchers who overextended the conclusions of a handful of small, questionably designed studies. Despite its good intentions, Housing First has failed as a policy framework for addressing homelessness in America. Our country and its homeless residents are now worse off today than 10 years ago when the policies of the HEARTH Act began to transform America’s approach to homelessness.

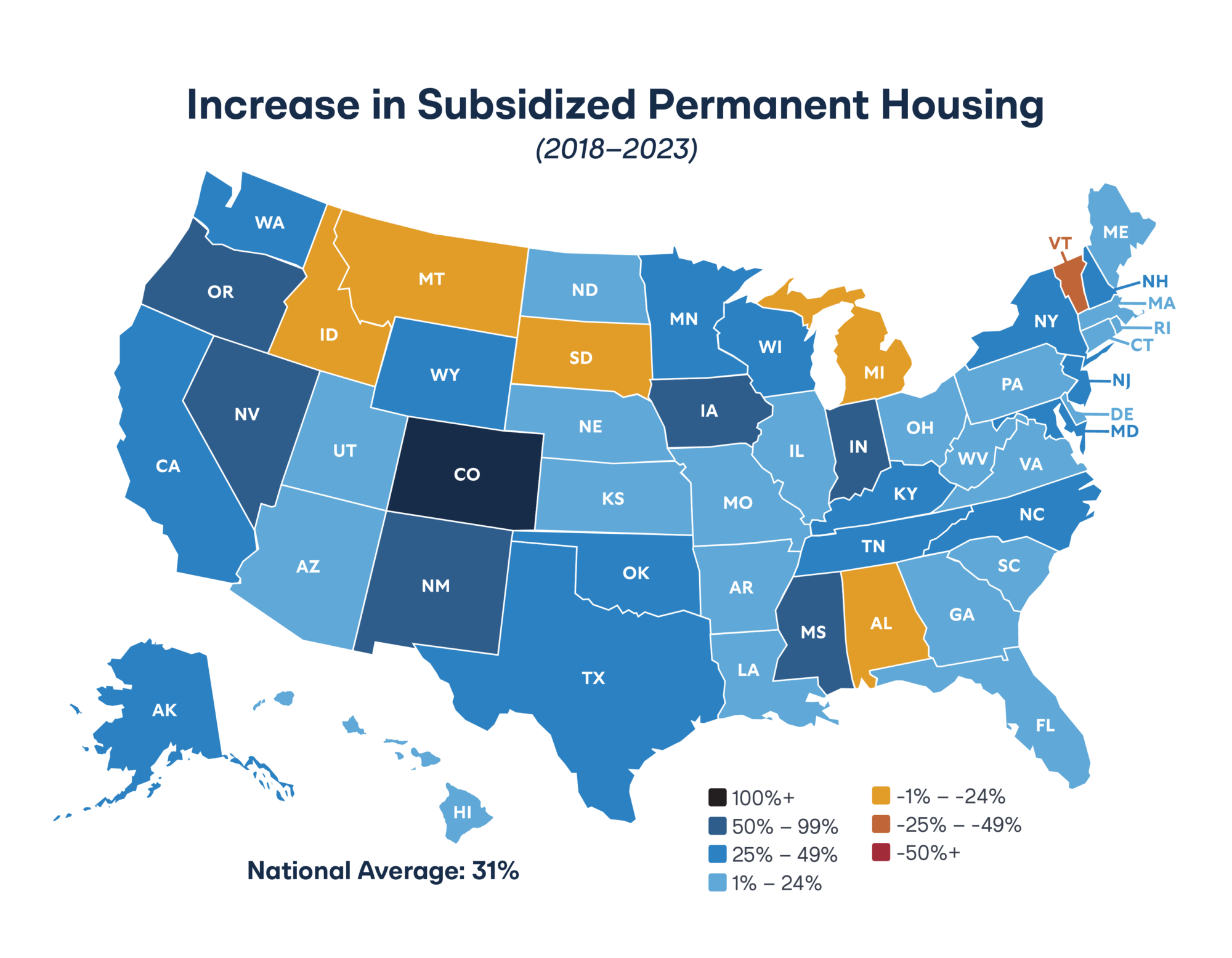

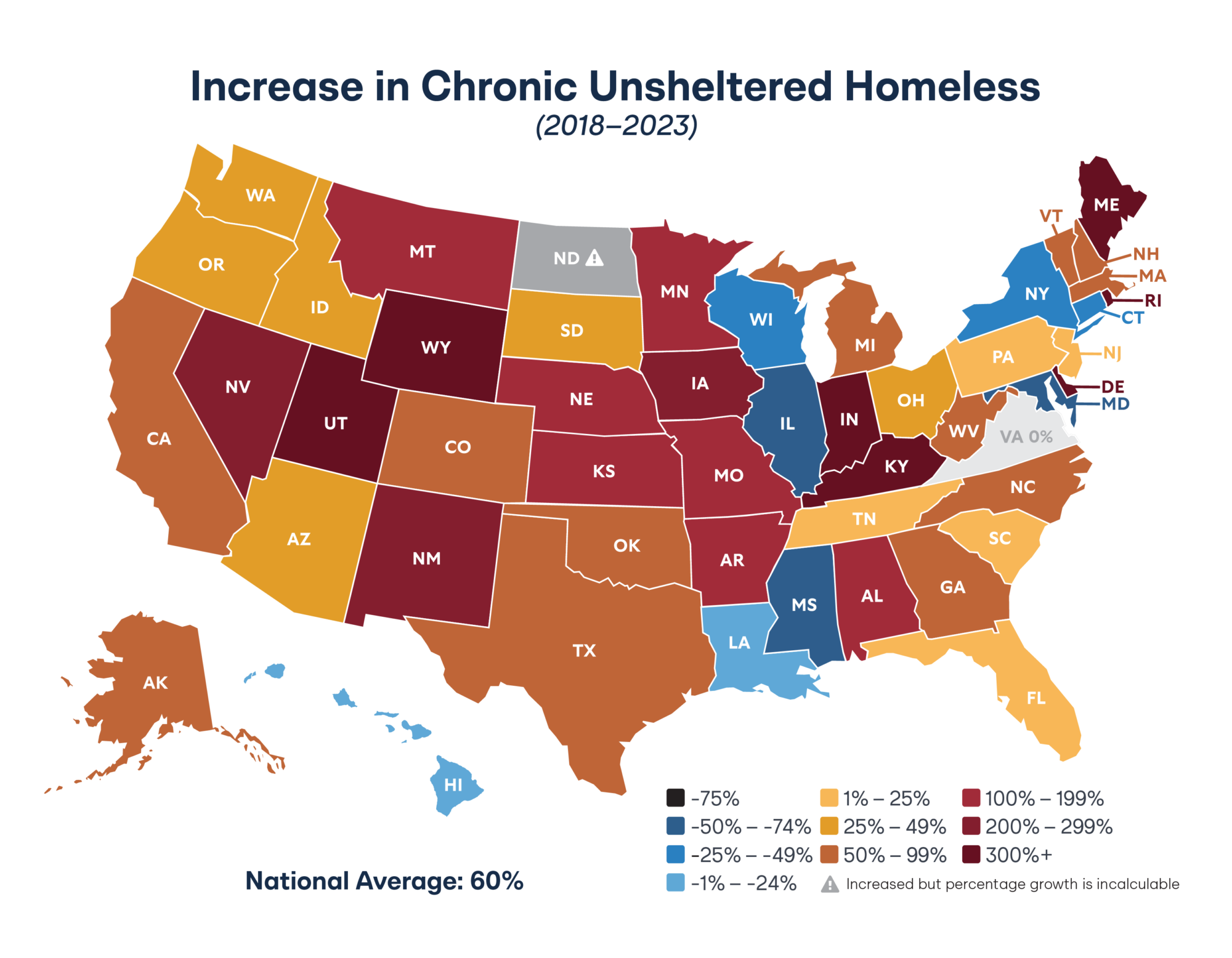

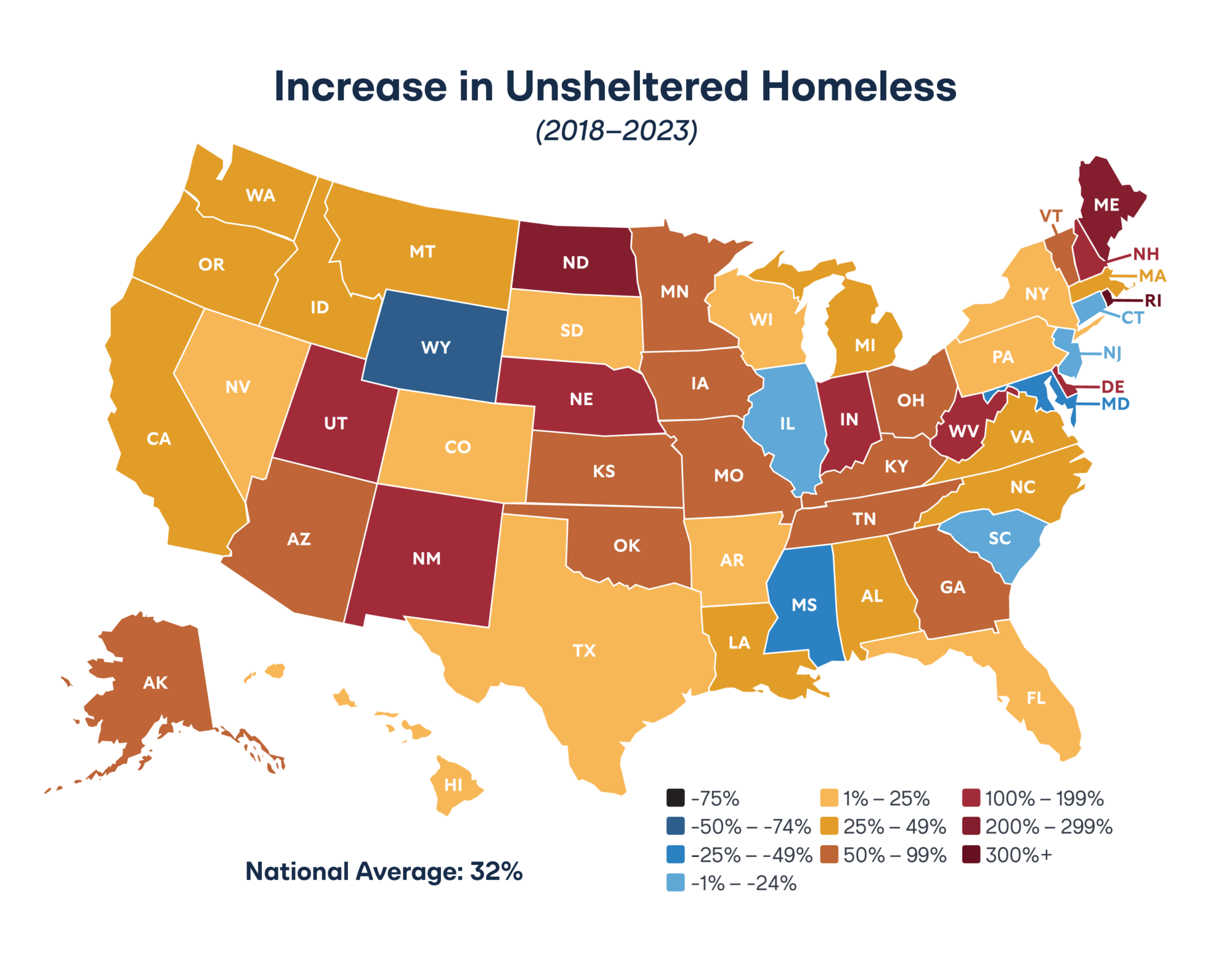

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, America has more than doubled its supply of permanent supportive housing since 2013, the hallmark intervention of Housing First.3 In addition, the U.S. has added 144,000 new units of rapid rehousing and 122,000 units of other permanent housing options for homeless Americans.4 In that time, Housing First policies have abated 120,000 units of transitional housing, which was the main intervention prior to Housing First.5 Yet, the proportion of homeless Americans who are without shelter has grown by 18 percent, rising at nearly double the rate of homelessness in general.6

Unsheltered homelessness, which refers to homeless individuals living on the street in tents and sleeping bags, has exploded nationally, rising 30 percent in 10 years.7 This cohort is extremely vulnerable and is more likely to include homeless individuals with severe mental illness or substance abuse. The proportion of homeless individuals with mental illness who are without shelter has increased by 19 percent, such that now nearly one in two of those individuals are unsheltered.8 For homeless people with substance abuse, that figure has increased by 51 percent, such that now 61 percent of them are without shelter.9 The trends in individual states are as much as two to five times higher in magnitude.

During the past decade, federal homelessness policies have failed to stem the growing desperation among America’s homeless, and by most metrics, it appears to have only added to their suffering.

What is Housing First?

Housing First is a policy strategy that seeks to expand government-provided long-term housing benefits for homeless individuals and prioritize housing stability by removing requirements for tenants—such as sobriety, engaging with caseworkers, or participating in treatment—which Housing First proponents argue are too onerous.i While it is promoted as an evidence-based policy approach to reduce the number of people living on the streets, its application does not accomplish this important objective. Because of that, the setbacks states have experienced using Housing First to respond to specific subpopulations of homeless people are not unique. In reality, this policy most often works to expand wealth transfers through housing subsidies and create large bureaucracies to coordinate, analyze, and plan while having little impact.

i. It is worth noting that much of the opposition is tied to the prospect of increased outcomes and accountability measures that would be placed on homeless service providers under Housing First reforms.

Housing First is the federal government’s preferred response to homelessness for organizations that receive funding from HUD. The origin of Housing First dates back to state-level programs in the late 1990s, but most of the effort to scale it nationally has occurred over the last decade.10

The expansion and implementation of Housing First is executed by Continuums of Care (CoCs), which are non-governmental, unelected regional consortiums of local stakeholder entities such as service providers, affordable housing developers, government agencies, advocates, and others.11 CoCs are responsible for approving and coordinating projects within their region that receive federal funding. These federal assistance grants are made for planning activities, services, and data management systems to create different types of housing for people experiencing homelessness and subsidize these projects’ rents. CoCs solicit project applications from local providers, and the governing members of the CoC score and rank projects to award funding.

Some states provide financial resources to CoCs, counties, and cities to supplement federal HUD awards. Funding can be significant (potentially hundreds of millions of dollars per year) but usually does not make up a majority of the resources dedicated to homelessness projects. Policies generally encourage leveraging local resources, including private philanthropic sources, to support the creation of an intricate network of services, outreach, and housing.12

CoCs are awarded grants to serve as collaborators, conveners, and coordinators so that homelessness efforts are implemented regionally and fall in line with HUD’s policy preferences. HUD prioritizes creating permanent supportive housing combined with case management and other services as its primary objective. It is very difficult to receive awards for other innovative approaches or housing that includes resident accountability.

HUD ties significant requirements and incentives to its Notices of Funding Opportunities (NOFOs), which the CoCs mediate. For example, HUD prohibits its grant recipients from requiring their clients to engage in any service, treatment, or program as a condition of receiving housing. This means that sobriety, drug testing, employment training, and participation in life-skills programs must be entirely voluntary.

HUD funding is heavily biased in favor of the Housing First approach. Project applications that do not utilize a Housing First approach are very unlikely to receive an award based on the scoring and ranking protocols of HUD and the CoCs— even though this type of permanent supportive housing (PSH) approach is not required. As a result, Housing First has been widely adopted by states and localities in their responses to homelessness.

Housing First is based on the theory that homeless individuals are best served by being offered stable, permanent housing (usually either PSH or rapid re-housing) that the government subsidizes without any conditions that might prevent them from accepting that housing or might cause them to get evicted. Once housed, these individuals are offered services they are free to engage with or decline.

To believe that the Housing First model is the right choice, one must believe four assumptions are true:

- That it is universally applicable to all types of homeless people.

- That subsidized housing must be offered indefinitely.

- That providers must take a harm reduction approach, which means that they should not require sobriety or engagement in services or treatment as a condition of housing or as grounds for eviction.

- That government-funded projects are a cost-effective and scalable way to respond to homelessness.

Limitations of Housing First

All four of the assumptions on which Housing First rests are deeply flawed—and America’s homelessness data highlights those flaws.

Universal Applicability

Following the scaling of Housing First, America effectively reduced the number of homeless people in some subpopulations. In contrast, according to HUD data, others were affected minimally by the expansion or were worse off.13 This demonstrates a problem with Housing First—that it serves a certain percentage of the population experiencing homelessness while being less effective with other populations, particularly those for whom the approach was originally intended. That includes people who are chronically homeless, unsheltered individuals with severe mental illness or substance abuse disorders, and homeless veterans. These populations tend to need more than just housing and may not respond adequately to completely voluntary services and treatment due to their complex high-risk, high-need conditions.

Most reviews of Housing First evidence come to this conclusion. Benston (2015) found no compelling evidence that Housing First programs positively affect mental health outcomes among homeless individuals.14 Chamber et al. (2018) found insufficient evidence of a positive relationship between Housing First and long-term physical or mental health. Still, they did find a relationship between treatment-oriented homelessness programs and improvements in health and well-being.15 The National Academies of Science commissioned an extensive review of available evidence for Housing First in 2018 and found no evidence that it improves health outcomes.16

As a result of Housing First interventions that are misaligned with the needs of homeless individuals, a substantial number of individuals who accept permanent supportive housing do not remain in it. Ten percent of the homeless population living on the streets of San Francisco in 2022 reported having already received permanent supportive housing before becoming homeless again—demonstrating that it is not a stable, long-term solution.17

The misapplication of permanent subsidized housing can lead to unintended consequences in certain demographics. For example, Carr and Koppa (2020) found that housing vouchers have a causal relationship with increased arrests for violent crime among male recipients and recipients of either gender with criminal history.18 A report on permanent supportive housing found that both total crime and violent crime increased within 500 feet of permanent supportive housing units, with a greater effect in the vicinity of large facilities.19

Despite Housing First’s limitations in applicability, most homelessness policies, programs, and plans provide little, if any, flexibility for local communities to address homelessness other than by providing permanently subsidized housing.

Permanence

Some service providers concede that some individuals reach a point in permanent supportive housing where they need to “move on” to new housing types. Offering subsidized housing on an indefinite basis is extremely inefficient. Not only does it prevent a housing unit from being turned over to serve a new person or family, but it also disincentivizes people from becoming independent once stabilized. Moreover, most cases of economically driven homelessness resolve themselves without government intervention. Permanent supportive housing gets recipients caught in the same trap as other forms of welfare: it reduces incentives to move off publicly-provided assistance rather than improving self-sufficiency.

Harm Reduction

Harm reduction is a theory centered on the premise that service providers should be led by the client rather than creating conditions the client must meet to receive services. While well-intentioned, in the context of homelessness, it can be very risky and has mixed evidence of success.20 The harm reduction approach of Housing First is based on Tsemberis, Gulcur, and Nakae, a landmark randomized control trial study (2004) which found that individuals who were offered housing without conditions remained housed at much higher rates while using substances at comparable rates to those who had housing conditioned on sobriety and treatment.21 This study, however, was limited in longevity and number of participants. While it was methodologically rigorous, more recent studies have shown signs of unintended negative consequences. For example, a recent study of the PSH program in Denver found that housing stability did improve under the program. However, the program had a 50 percent higher mortality rate compared to the control group.22

The alarming expansion of severe mental illness and chronic substance abuse among homeless individuals in America warrants scrutiny of the appropriateness and effectiveness of the harm reduction approach, as well as the potential unintended consequences of such policies.

Cost-Effectiveness and Scalability

Housing First advocates frame their policies as being cost-effective compared to other models. Many studies appear to demonstrate the advantages of Housing First, but these studies are relatively small, address marginal impacts of homelessness assistance programs, and have not been shown to scale effectively—if at all. There are serious flaws in the methodologies of the research that support claims of cost savings, namely that the studies examine average costs of services rather than marginal costs, as explained in Benston (2015).23 A systematic review of Housing First research from the National Academies of Science found insufficient evidence to conclude that Housing First programs reduce healthcare costs or are otherwise cost-effective.24

Moreover, it is doubtful that government-funded construction projects are the most cost-effective way to expand low-income housing. A recent study found that, for every 100 bedrooms of market-rate housing, the migration of under-renting individuals to higher-cost housing makes between 45 and 70 bedrooms of lower-income housing available.25 In comparison, a national study of Housing First, Corinth (2017), found that an increase of 10 permanent supportive housing beds was required to reduce homelessness by one individual in America.26 This study demonstrates that permanent supportive housing is not efficacious—and it is far from cost-effective.

Other Considerations

Another curious aspect of the Housing First model lies in its proponents’ certainty of its efficacy, surmised in the National Alliance to End Homelessness’s slogan: “We know how to end homelessness.”

Advocates base their confidence on a policy shift that has homeless individuals sign a lease agreement rather than a program contract, changing both the relationship and the rules. Before adopting the current federal policy on homelessness assistance, shelter and transitional housing programs used program contracts instead of leases as the main strategy to address homelessness. These programs, called linear models, focused on measurably improving a person’s stability as a prerequisite for obtaining independent housing.27

Advocates of Housing First pointed out that if a participant exited from or completed a program, there was no guarantee of securing housing. The solutions, they posited, were to forego the programmatic elements of addressing an individual’s needs and, instead, sign that person to a lease where they would no longer be program participants but tenants. As tenants, issues such as idleness, substance use, or even mental illness would be protected by the Fair Housing Act as long as the rent was paid.28 And often, rent is paid by a third-party nonprofit or a government assistance program—disincentivizing tenant accountability.

Therefore, the organization’s confidence in proclaiming “we know how to end homelessness” does not come from its success in addressing the challenges of the indigent so much as in pulling off an accounting gimmick. If someone has a lease, regardless of their ability to maintain it, they cannot be counted as “homeless.”

These significant flaws in the Housing First model call into question HUD and CoC’s singular focus on expanding it. State governments are uniquely positioned to invest their resources in approaches that fill in the gaps left by Housing First and begin to pressure their service providers to move in a new direction.

State-Level Solutions to Better Address Homelessness

The federal government’s preoccupation with Housing First is unlikely to change quickly. This reality leaves states with the onus to move their communities in a different direction using the funding and policy levers available to their legislatures and executives. State-level changes can do little to change the policy priorities of CoCs. Still, they can create pressure in certain areas and leverage federal funds to foster state-level innovation in their approaches to homelessness.

The policy solutions recommended in this report fall into six broad categories: data and performance measures, addressing street homelessness, expanding and improving short-term housing, creating accountability for long-term housing, responding to crime, and disrupting the prison-to-homelessness pipeline.

1. Data and Performance Measures

The primary method of collecting data on homelessness is HUD’s Point In Time (PIT) count.29 This count, which is intended to be an estimate of the number of people experiencing homelessness in the service area of the CoC, is required by HUD for CoCs to receive grants. However, due to the methodological limitations of PIT, HUD does not use this data for accountability. Municipalities and states are allowed to conduct their own data collection and homelessness census programs that would provide better data—and, therefore, a better idea of how local programs are performing—but few do.

To track data, HUD requires communities to invest scarce resources in its costly, complex, and marginally effective Homelessness Management Information System (HMIS).30

The data that the CoC is required to collect is meant to be uploaded to HUD so that HUD can compile its Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) for Congress.31 The AHAR compiles demographic statistics of who is experiencing homelessness and data at the CoC-and state-level. It is very difficult to determine whether homelessness is increasing or decreasing by the AHAR. It is even more challenging to determine whether local efforts are successful in reducing the number of people living on the streets—or if they are achieving success at all.

HUD’s focus on process measures instead of outcomes data makes it difficult to determine the effectiveness of interventions at scale. Because CoCs are focused on internal data collection, this data can have little bearing on what is actually happening on the ground in terms of drivers of homelessness, the effectiveness of one program over another, changes in the population, or the impact of creating affordable housing in reducing the numbers of individuals experiencing homelessness.

Since HUD characterizes homelessness as primarily an issue of affordable housing, their data collection pays little attention to the expense or impacts of homeless encampments, environmental destruction from people living in public spaces such as parks or on sidewalks, and municipal costs to address vandalism, safety concerns, and quality of life changes. In this way, municipalities pay for the negative consequences of the homelessness assistance program.

Policy Proposal No. 1: Performance Audit & State/Local Data Collection

States should conduct program evaluations and performance audits of organizations that receive government funds to serve homeless populations. These audits will offer state policymakers an overview of what is currently being spent and from what sources; what data are collected in relation to those programs; what outcomes these programs have achieved; and identify gaps in services, data collection, and performance evaluations. This is an essential starting point for effective state-level policymaking to address the shortcomings of the federal approach, and states already have a model example in Georgia, which has led the effort by instituting audits of state-funded homelessness programs.32

Using the information from performance audits, policymakers can develop state-level data collection that is tailored to the needs of their communities and the metrics that are important indicators of success. While HMIS is costly, rigid, and overburdened by regulatory guidance and privacy requirements, a host of data-collection companies can help local governments better understand what is happening in their communities. Start-up vendors like Nomadik AI offer a more rigorous and helpful approach to collecting data and tracking the public health and public safety risks of homeless encampments in real-time.33 Improved data collection is an essential step towards accountability and transparency in homelessness policy.

2. Addressing Street Homelessness

Street or unsheltered homelessness is a distinct category of homelessness made up of people who are not sleeping in shelter spaces but in tents, cars, RVs, and makeshift shelters. These unsheltered homeless individuals face significant challenges compared to sheltered homeless individuals. And over the last five years, their challenges have gotten much worse.

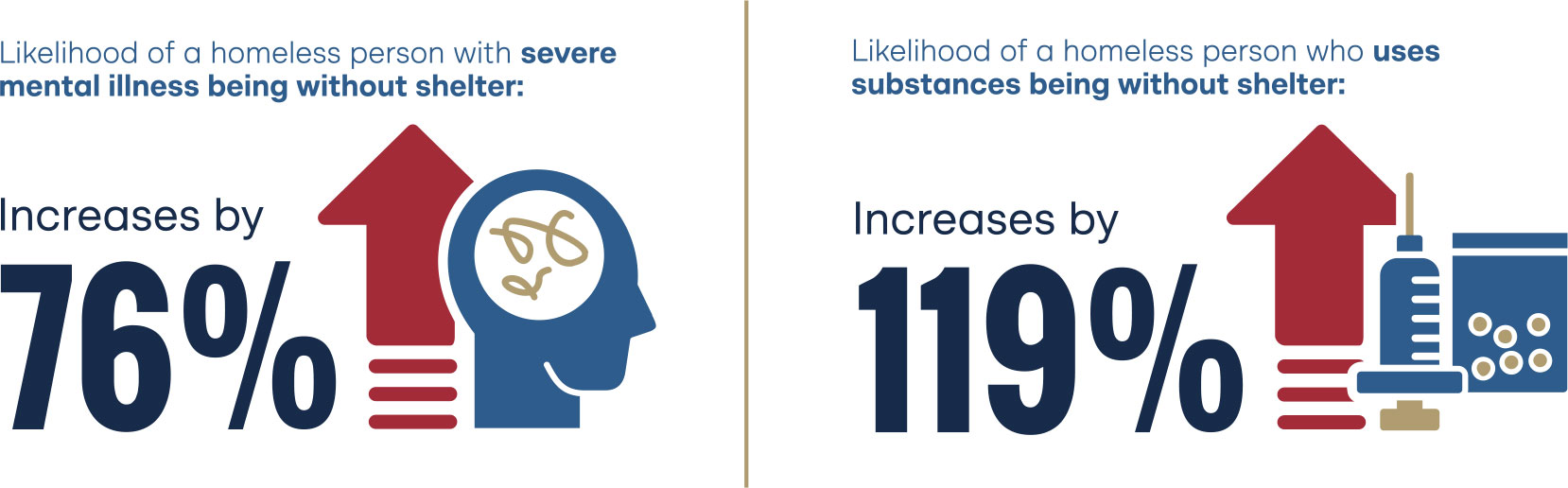

Since 2018, the likelihood of a homeless person with severe mental illness being without shelter has grown by 76 percent; among homeless people who use substances, the proportion without shelter has increased by 119 percent.34

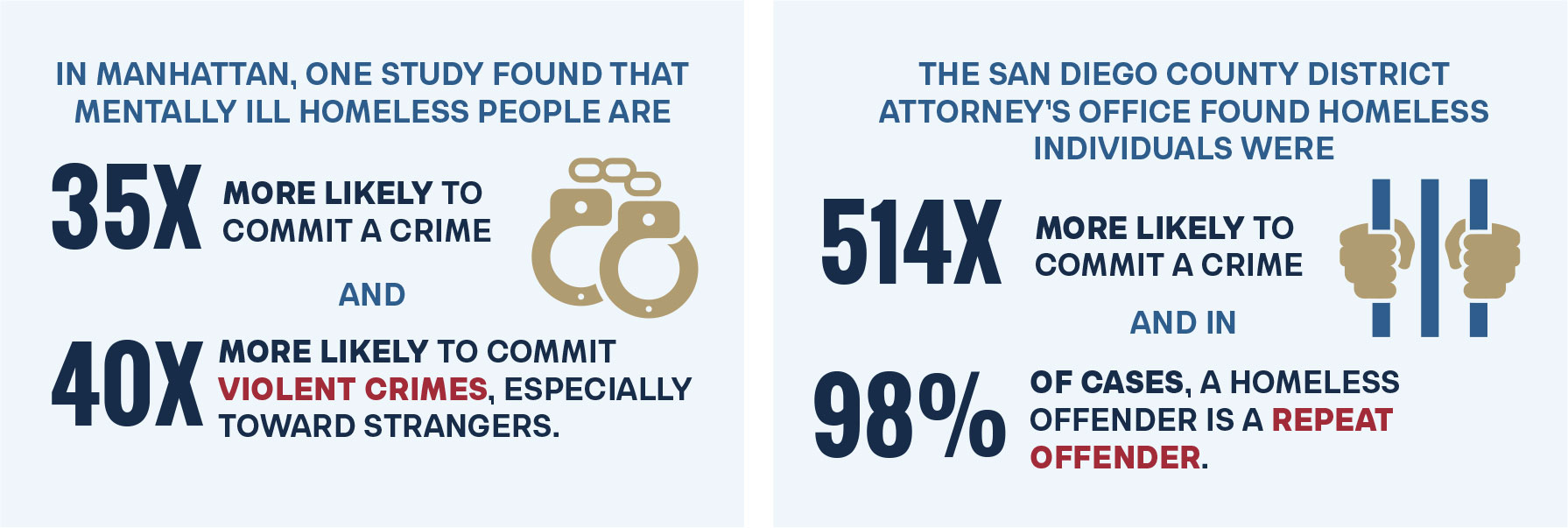

The conditions unsheltered individuals are exposed to are dangerous for themselves and the community more broadly. The prevalence of crime, mental health and substance abuse disorders, and incarceration among the homeless population is staggering. In Manhattan, one study found that mentally ill homeless people are 35 times more likely to commit a crime and 40 times more likely to commit violent crimes, especially toward strangers.35 The San Diego County District Attorney’s office found homeless individuals were 514 times more likely to commit a crime than the average citizen, and in 98% of cases, a homeless offender is a repeat offender.36

Homeless individuals are at a higher risk of communicable diseases due to the circumstances of their living conditions. The National Institute of Health (NIH) found that unsheltered homeless individuals have a nearly three-fold increase in mortality compared to their sheltered counterparts due to a variety of factors, including drug-induced poisonings and infections.37-38 Diseases like shigella and tuberculosis spread rampantly among individuals who live in close quarters without sanitation or waste management. Despite making up less than 0.2 percent of the population, homeless individuals account for five percent of incidents of tuberculosis.39

Allowing street camping is an unacceptable dereliction of care for the most vulnerable of homeless subpopulations, especially in states like Nebraska, which have enough shelter space for all homeless people.40 From obstinance towards authority to habitual fondness for camping, to substance abuse or having pets, chronically unsheltered homeless people sometimes refuse available shelter for a variety of reasons. This population is commonly referred to as “shelter resistant” and whatever their reasons for shelter refusal, they do not override communities’ public health and safety interests when it comes to dismantling street encampments.

Policy Proposal No. 2: Prohibit Unauthorized Street Camping

Banning street camping is an effective way to close dangerous homeless encampments and divert vulnerable homeless individuals to the resources they need to rebuild their lives—and there is precedent for its success. Austin, Texas, saw its unsheltered downtown area homeless population drop by one-third following the reinstatement of its camping ban in 2021.41

State legislatures can take action to prohibit street camping and dismantle dangerous homeless encampments. First, states should ban unauthorized camping on state land by instituting a low-level criminal offense such as a minimally classed misdemeanor. Second, states should create courses of action for litigation or writs of mandamus against municipalities that refuse to clear encampments or those that subvert the state by removing local ordinances against street camping. These lawsuits could be brought either by state attorneys general or residents. Third, states should withhold certain types of funding related to homelessness for municipalities that are out of compliance with state or local law.

The prohibition of street camping recognizes the fundamental danger of unsheltered homelessness, but it should not be focused on punishing homeless individuals. On the contrary, it empowers law enforcement as a last-resort intervention for shelter-resistant individuals who may be of especially high risk and need when homeless outreach teams fail to persuade them to engage with services. Most of these laws require that officers provide warnings before issuing a citation or making an arrest. Moreover, removing criminal laws against street camping can actually lead law enforcement to rely on higher-level offenses like trespassing or public endangerment to clear encampments instead. Camping bans are a straightforward way to move people into services with accountability and compassion.

Policy Proposal No. 3: Create Designated Camping Sites

States should consider creating grants to create designated camping areas in municipalities with the highest levels of homelessness.

Designated camping sites can offer affordable, fast-to-build, and safe alternatives to street camping—especially when communities do not have enough temporary shelter space available or when a high proportion of the unsheltered homeless population is shelter-resistant. Designated camping areas can include security to keep residents safe and sanitary stations that offer potable water, showers, toilets, soap, and other necessary amenities. And by centralizing the unsheltered homeless population in specific areas, medical and mental health providers, as well as outreach teams, can more easily offer services and create an on-ramp to shelter and housing. Several cities around the country have successfully implemented this innovative model.

Portland, Oregon, has authorized a designated camping area called “Safe Rest Villages” that has served 345 people since opening, 33 percent of whom were—or are—chronically homeless. Seventy people have exited the camp to transitional housing, and camp services have helped obtain 169 identifying documents (identification cards, birth certificates, etc.) for residents.42

Denver, Colorado, currently has three designated camping areas called “Safe Outdoor Spaces” (SOS), which housed 242 people and helped 47 transition into stable housing in 2022. Despite overall crime in Denver increasing by 14 percent in 2021, crime in the areas near designated SOS spaces decreased by nearly three percent. Police say no resident has been charged with a crime while living in any SOS site.43

Austin, Texas, implemented the first designated encampment in Texas on land provided by the state in 2019. Currently, there are 80 homes with services provided by The Other Ones Foundation (TOOF) on a 10-year lease. TOOF states it helped 170 residents find housing in 2022.44

Seattle, Washington, has three designated encampments available for homeless individuals. A 2017 evaluation found that they did not increase crime in the areas and that surrounding communities responded favorably to the sites.45

Designated camping facilities provide a safe space alternative to street camping that creates an on-ramp to higher tiers of shelter, housing, and services or treatment.

Policy Proposal No. 4: Support Street Medicine

The severe public and individual health risks correlated with unauthorized street camping and unsheltered homelessness warrant healthcare interventions in addition to shelter and law enforcement. Many homeless individuals, whether unsheltered, in an emergency shelter, or in a designated encampment, struggle to access healthcare due to the communications, scheduling, and transportation barriers involved. One alternative mode of care is street medicine, which brings healthcare providers to patients instead of requiring patients to visit a traditional office.

Street medicine is still fairly limited in the United States and is typically funded with grants that often lack stability and reliability.46 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recently included street medicine as a covered service with Place of Service Code 27 (“outreach site or street” billing code).47 States can now implement this change through a state plan amendment or bulletin to providers. This change can promote medical care through street medicine for those who have difficulty accessing care while homeless.

Street medicine is an important tool for determining the level of acuity in unsheltered individuals. For those identified as high-acuity (their condition is severe and imminently dangerous), street medicine staff can be instrumental in providing a clinical foundation for court-ordered treatment, assisted outpatient treatment, and the administration of long-acting antipsychotics to stabilize health.

Policy Proposal No. 5: Train “First Contact” Personnel to Estimate Behavioral Health Acuity

Outreach workers, shelter operators, housing navigators, street medicine professionals, law enforcement personnel, and others who regularly engage with people experiencing homelessness should have the training to estimate mental and behavioral acuity. Far too often, individuals with high behavioral health acuity are left untreated and unsheltered because first-contact personnel are ill-informed on the urgency of the issue and the resources available.

Individuals struggling with mental illness or substance use disorder could be referred to behavioral health and addiction recovery services as a part of the behavioral health continuum of care. This potentially life-saving referral can only be accomplished if outreach workers consider the behavioral health needs of these individuals beyond their need for housing.

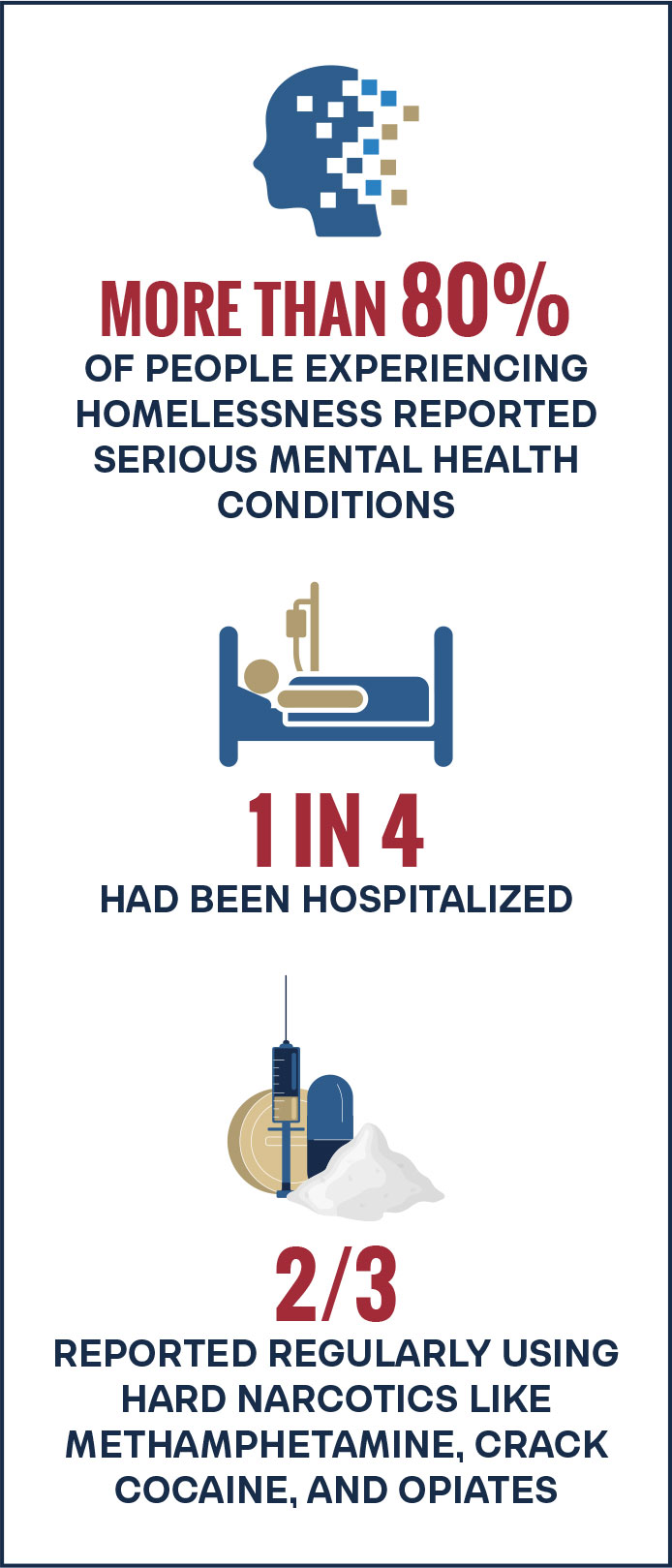

A study found that more than 80 percent of people experiencing homelessness reported serious mental health conditions, for which one in four had been hospitalized. Two-thirds reported regularly using hard narcotics like methamphetamine, crack cocaine, and opiates, fewer than half of which reported ever receiving treatment. A mere four percent cited high housing costs as the primary reason they became homeless.48

Training first-contact personnel to recognize and estimate the behavioral health acuity of people experiencing homelessness will ensure and enhance the ability of those individuals to receive the appropriate services from the appropriate providers in the continuum of care. In the case of law enforcement personnel, training can also help reduce the unnecessary involvement of some homeless individuals in the criminal justice system while still upholding public safety.

Policy Proposal No. 6: Direct Mental Health Funding towards Homelessness

Behavioral health needs have a significant impact on the trajectory of homeless individuals. Community mental health centers and other organizations that offer services to individuals with intensive behavioral health needs, and who are at a high risk of becoming homeless, need the resources and latitude to intervene before that occurs.

As such, states should marshal mental health resources to address the needs of homeless and at-risk individuals. Most recently, Florida and Georgia have successfully redirected funding for Housing First projects towards treatment and treatment-oriented services and shelter as part of their homelessness reforms.49

The primary sources of funding in state departments of Health and Human Services (HHS) that can be used to address homelessness are Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) grants. Several SAMHSA grants are available to states, including the Community Mental Health Block Grant and the Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant. States have considerable latitude in how they use these grants as long as the uses are consistent with the purpose of the grant program’s broad terms and conditions.

State HHS departments should review current grant-funded programs to measure effectiveness and opportunities to reconfigure funding models to incentivize outcomes that better address the needs of a growing high-risk homeless population.50

Policy Proposal No. 7: Expand Shelter and Transitional Capacity in High-Need Areas

It is difficult to determine the true alignment of capacity with the demand of the homeless population due to geographic distribution within that region and seasonal variability. Still, states should undertake an assessment of these needs and consider making investments in the necessary areas.

Policy Proposal No. 8: Improve Involuntary Commitment Procedures

Some homeless individuals who suffer from severe mental illness (SMI) pose a very high risk to themselves and the communities in which they live. Involuntary civil commitment is an essential tool that can help get individuals the they desperately need but might refuse due to the complexity of their conditions. Involuntary treatment, when used prudently, is shown to reduce incidents of crime, homicide, and suicide, and improve long-term outcomes for individuals struggling with mental illness.51

Involuntary civil commitment can include inpatient and assisted outpatient treatment, depending on resources and the individual’s needs. In conjunction with street medicine, assisted outpatient treatment can provide much-needed care to individuals who are not yet consistently involved in treatment, services, or shelter.

Policy Proposal No. 9: Utilize Homeless Diversion Programs to Mandate Shelter and Treatment

For homeless individuals who end up in the criminal justice system for lower-level, non-violent offenses and would be better served by a treatment-centered approach, states should create diversion programs. These programs, which would be specifically for homeless individuals, can leverage the accountability mechanisms of the criminal justice system to offer individuals a level of care that is more regimented than entirely voluntary programs, but less invasive than involuntary programs. Participant interventions could be tailored to the individuals and include services such as outpatient drug or mental health treatment or might involve compliance with camping bans and utilizing available shelter space instead of sleeping on the street. After a set duration of intervention, the individual would exit the criminal justice system without a conviction on his or her record. If the individual fails to comply with the terms of the plan, then the prosecutor and judge could pursue accountability through traditional legal means.

3. Expanding and Improving Short-term Housing Policy

Proposal No. 10: Rebuild Transitional Housing Capacity

America has lost approximately 60 percent of its transitional housing units between 2013 and 2023.52 Transitional housing is an essential component of the continuum of services for homeless people who need additional support and accountability and may not be successful with greater autonomy. The federal restrictions on permanent supportive housing care standards are too lenient and, for some individuals, emergency shelter imposes too many restrictions. Transitional housing provides a necessary steppingstone to independent housing, yet most states lack this capacity. The federal prioritization of Housing First contributed to this gap, and in response, states should prioritize investments in transitional housing instead of permanent housing-based interventions that lack accountability.

Policy Proposal No. 11: Create Accountability for Transitional Housing and Rapid Re-Housing through Outcome-based Funding

Simply funding new housing-related programs is insufficient to ensure a well-functioning response to homelessness. Financial incentives are a powerful motivator, and too often the financial incentives of organizations that serve struggling populations are incentivized to perpetuate the problem, Outcomes-based funding models have shown considerable success in the homelessness and criminal justice spaces.53

In 2016, HUD partnered with the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) to offer a number of transitional housing outcome-based “pay for success” programs, allocating $8.68 million in grants with six-year implementation and evaluation periods.54 Pilot locations under current evaluation included Anchorage, Alaska; Pima County, Arizona; Los Angeles, California; Prince George’s County, Maryland; Lane County, Oregon; Rhode Island; and Austin, Texas.55

An additional project with a similar model was conducted in Salt Lake County, Utah, and evaluated with a rigorous randomized control trial. Utah’s REACH program was remarkably similar, although it focused on individuals transitioning out of the criminal justice system rather than out of homelessness. It was implemented and evaluated in tandem with a program focused on homelessness, and while full reports are forthcoming, both have had strong outcomes.56 These models should be expanded to include any state funds going to transitional housing or rapid rehousing programs, and reporting should include metrics not only related to housing attainment and retention but also related to treatment engagement.

4. Creating Accountability for Long-term Housing

Policy Proposal No. 12: Create Accountability for Long-term Subsidized Housing Programs through Outcome-based Funding

Permanent supportive housing will continue to be the federal government’s priority for the foreseeable future. Given that state funds often get ensnared in federally funded projects, they should try to leverage what little control they have, to promote treatment. States cannot require federally funded programs to engage participants with treatment or other priorities because the state would be in conflict with HUD’s guidance, but they can—and should—prioritize state-matching funds to CoC projects that include outcome-based funding models. These funding models reward a variety of key metrics, including engagement with treatment, which can help states encourage a treatment-oriented model even within the confines of HUD’s guidance.

5. Responding to Crime

The public disorder associated with homelessness sometimes follows individuals from the street into areas where they receive shelter, services, and other support. Moving people off the street and into shelters is an effective way to reduce public camping—which is the riskiest mode of homelessness in terms of both public health and public safety—and some of the crimes associated with it.57 But there is much that needs to be done to ensure a safe transition from the street into a more stable environment. A study from the RAND Corporation and the University of Pennsylvania found that homeless shelters increased property crime by 56 percent within 100 meters of the shelter while reducing criminal trespass by only 34 percent.58 The study also found that the impact on crime was limited to the immediate vicinity of the shelter, with effects dissipating over two to three blocks of the shelter. Another report on permanent supportive housing for homeless people found that both total crime and violent crime increased within 500 feet of permanent supportive housing units, with a greater effect in the vicinity of large facilities.59 These findings are consistent with more extensive reviews of available studies that found permanent supportive housing does not reduce criminal activity among people who are homeless.

Moreover, there is substantial evidence that permanent supportive housing has no discernable positive impact on illicit drug outcomes for homeless people.60-61 In addition to the public safety risks posed by street homelessness and crime, there are substantial public health risks to homeless people themselves with regard to drug use. The harm reduction approaches of homeless outreach teams and Housing First programs underestimate the lethality of even a single dose of certain drugs. The latest available data shows 108,000 Americans died of a drug-involved overdose in 2022.62 More than twice as many people died of overdoses from synthetic, non-prescription opioids—namely fentanyl—than from stimulants like cocaine and methamphetamine. Of deaths resulting from cocaine or methamphetamine overdose, a sizable majority also involved opioids.63

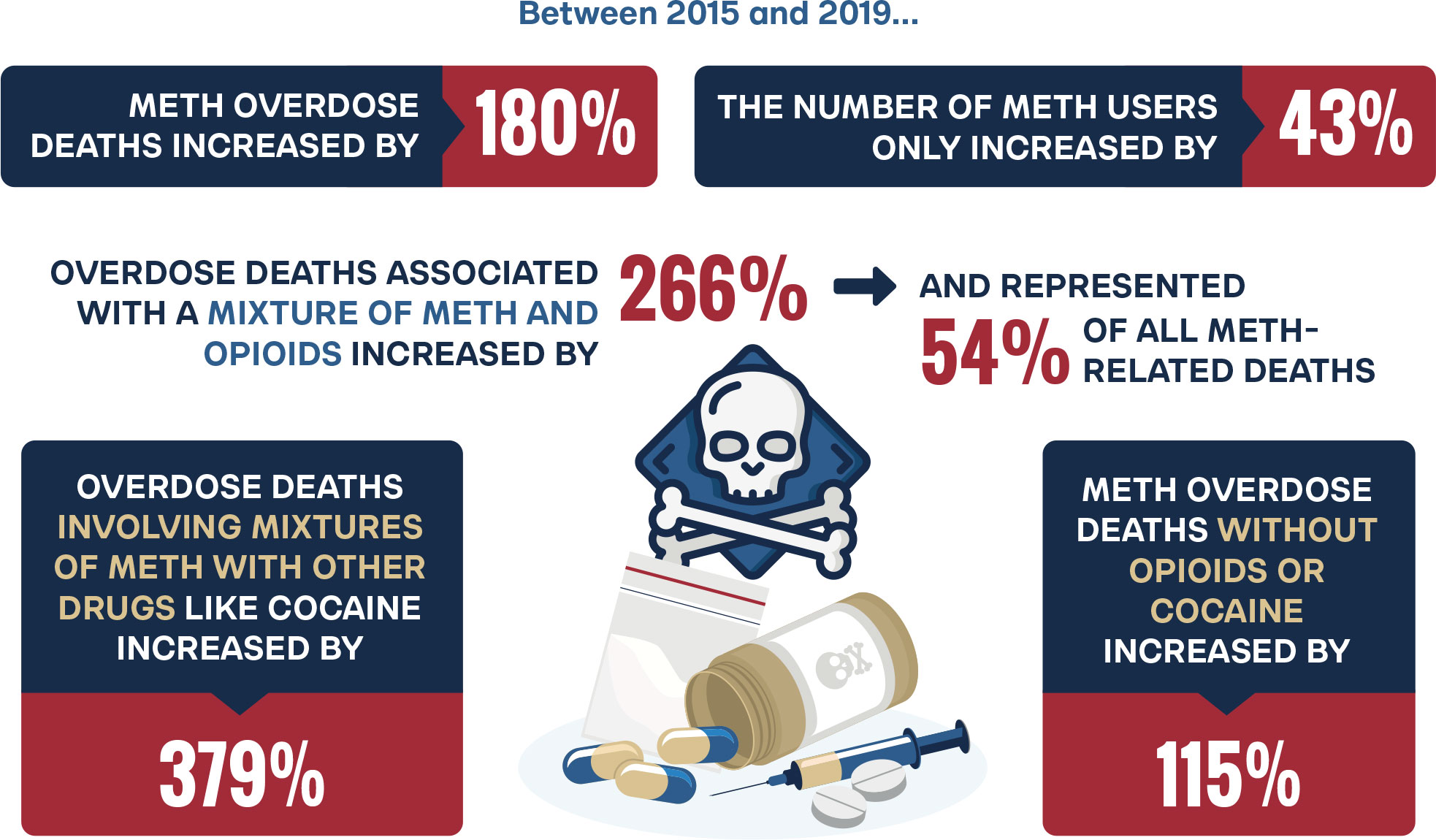

Drug use has become more dangerous than it was in the past, in large part because of the prevalence of potent opioids like fentanyl and similar substances. In the case of methamphetamine, overdose deaths increased by 180 percent between 2015 and 2019, while the number of users over that same period increased by only 43 percent.64 When overdose deaths are sorted by both drug type and the presence of other substances, a clearer picture emerges. The number of overdose deaths associated with a mixture of methamphetamine and opioids increased by 266 percent between 2015 and 2019 and represented 54 percent of all methamphetamine-related deaths.65 Overdoses involving mixtures of methamphetamine with other potent drugs like cocaine also saw considerable growth—379 percent—but represented a much smaller proportion of total deaths at only 11 percent.66 In comparison, the number of deaths associated with methamphetamine overdose without opioids or cocaine increased by 115 percent over the same period.

Another factor that contributes to the deadliness of drug use is environmental—such as whether someone uses drugs while alone, as is often the case in a permanent supportive housing unit without treatment or supervision. Studies have found a high proportion of drug-related deaths occurred when a person used drugs when they are alone.67

Given the high rates of crime and drug use involving people who are homeless, shelters and other housing and support services must do more to improve these outcomes. This is the only way to successfully uphold order in their facilities and public safety in the vicinity.

Policy Proposal No. 13: Create Drug-Free Homeless Service Zones

Drugs exacerbate the challenges facing the homeless by exposing them to criminal predation, attracting criminal activity and disorder that further destabilizes their environment, and enabling criminal behavior among them. Drug dealers who target homeless people take advantage of their vulnerability due to extreme economic distress and serious mental health conditions, eroding public safety. It is imperative that policymakers curb the prevalence of illegal drug markets near areas that serve the homeless so struggling individuals can have a better chance at success.

Throughout the 1980s, all 50 states created drug-free zones to counteract the encroachment of drug dealing and use into concentrated areas of children, such as those near schools, daycares, and school bus stops. Many states required these areas to have signs that read “Drug Free Zone,” warning of enhanced punishments if the signs were ignored. Studies found evidence that these policies were effective in significantly reducing drug crimes near schools.68–69 Other studies note that the primary limiting factor of these policies is keeping the zone size small enough to effectively deter drug dealing from the immediate vicinity of the property.70 These findings are consistent with elements of other place-based crime studies, including those focused on homeless shelters.

Policymakers should create drug-free zones around homeless service areas that offer housing, shelter, or other assistance to homeless individuals. These policies should focus on deterring the encroachment of the illegal drug market into the vicinity of homeless services but also hold facilities responsible for creating a safe and secure environment for their clients. Drug-free homeless service zone laws enhance criminal penalties for selling, possessing, or transferring narcotics within 300 to 500 feet of a facility—the radius range that studies found was most susceptible to criminal activity around a homeless shelter or supportive housing facility.

The second component of the law includes financial penalties for homeless service providers who permit (either in policy or practice) the possession, sale, transfer, or use of illegal drugs among their clients. It is increasingly common for homeless service providers to permit drug use in their facilities and de-emphasize treatment as part of a “harm reduction” approach to housing. Because of this predatory dynamic, drug-free homeless service zones should penalize service providers that enable drug crime and usage for failing to maintain a safe environment for their clients. Providers who turn a blind eye to a dangerous environment for the vulnerable population they serve should be held accountable. Fining facilities would create a powerful incentive for service operators to prioritize treatment and other interventions rather than enabling dangerous behaviors like drug use.

The connections among drugs, crime, sex trafficking, homelessness, and facilities that provide services to the homeless are alarming. Many service providers, encouraged by federal agencies, have neglected the risks posed by drug use and crime to homeless individuals—particularly women and children—and the community. Policymakers need to do more to intervene appropriately in this growing crisis by holding both criminals and service providers to account for contributing to the problem. Creating drug-free zones is a proven model that can help save lives, reduce crime, and restore life on America’s streets.

In addition to legal sanctions, states and localities should revoke the operating licenses of shelters and providers that repeatedly violate the standards set by drug free homeless service zones or obstruct law enforcement in conducting necessary searches to ensure those standards.

6. Disrupting the Prison-to-Homelessness Pipeline

Roughly half of people in homeless shelters have been to prison, with one in five having left within the last three years.71 The University of California at San Francisco reported in June 2023 that nearly one in three homeless people in California had been to prison or served a long-term jail sentence in the six months before becoming homeless.72

People who have recently been released from prison have a higher risk of becoming homeless than any other group in America.73 Within the first two years of release, approximately 11.4 percent of those exiting prison use a homeless shelter, with the greatest portion experiencing homelessness within their first 30 days post-incarceration.74 Prisons provide minimal support and transitional services to ex-inmates, and those that do offer help have little incentive to deliver these services effectively to improve outcomes for their “clients.” It is no surprise, then, that more than one-quarter of the formerly incarcerated experience “a trajectory of persistent desperation and struggle, [with] frequent periods of homelessness and housing instability.”75

Policy Proposal No. 14: Create Accountability for Re-entry Housing Outcomes from Prison

The pay-for-success models discussed earlier can be applied to re-entry housing for individuals leaving prison. Rewarding organizations that support better outcomes for people leaving prison while holding organizations accountable for bad outcomes can disrupt both cycles of crime and the pipeline from prison to homelessness. Stabilizing former offenders at extremely high risk of homelessness should be a top prevention strategy for states. Pennsylvania successfully implemented outcome-based contracts for their community corrections providers in 2015, seeing substantial reductions in recidivism following the implementation of new contracts.76

Conclusion

States must reassert their autonomy over the homelessness policies in their own state and local communities. After decades of ceding responsibility to the federal government, most communities are significantly worse off. Most notably, unsheltered homelessness and the changing composition of needs among that population are presenting unique challenges for which HUD policies are ill-equipped. States should reject Housing First and chart a new course that is aligned with their values and evidence from the failures of the last 10 years.