Transparency and Accountability for School Spending

Three decades have passed since the enactment of the federal Elementary and Secondary Education Act in 1965 as part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “War on Poverty.”1 During that time, per-student expenditures grew by 115% in constant dollars, but it was hard to know whether educational achievement was increasing too. And so, in the 1990s, assessments such as the National Assessment of Educational Progress were deployed to measure things like fourth grade reading scores. Over the subsequent three decades, those scores improved only slightly while spending jumped an additional 50% in constant dollars.2 This expensively obtained, minuscule advance was later wiped out by COVID shutdown policies, and in 2022, fourth-grade reading scores dropped back to 1992 levels.3

In response to these spending and academic non-achievement trends, the 1990s and early 2000s saw the growth of a fundamental fault line in American politics over the following question: Is it better to put our focus on increased spending or increased efficiency in elementary and secondary education?

Despite evidence to the contrary, parents have been told for more than 50 years that more money will solve public education’s woes, from increased staffing to better curricula. Yet, little attention has been given to the actual outcomes of throwing good money after bad. And even less focus has been given to schools with greater challenges in producing academic excellence. What’s needed are solutions that prioritize smarter spending over flooding poorly performing models with more cash.

To achieve these aims, parents, reformers, and the public need and deserve more information about where the money currently goes. Implementing ambitious transparency at the state and district level is the key first step to unlocking better-informed local decision-making, especially when local officials are trained on how to understand and act upon these data.

At the state level, this should be coupled with robust oversight to investigate fraud and address misconduct to improve governance and empower parents to hold schools accountable when it comes to spending. States can ensure transparency in the implementation and execution of new spending models by requiring and facilitating transparency and ensuring the information is readily available to and understandable by the public.

Other policies can help, too. Collaboration between state education departments and private sector experts can empower school leaders to learn from what is working elsewhere. Prioritizing voluntary union membership, redirecting funds to academics, and aligning curriculum with the “science of reading” are all vital strategies for educational improvement that may work in conjunction with improved transparency.

At the macro level, we now have decades of ever more precise data showing us that how money is spent is a far better predictor of student success than overall spending—most of which has gone to increases in staffing that haven’t produced better outcomes.4 These lessons can help us enact new policies that ensure educational funds—no matter their amount—are spent wisely and, if the case is made to spend more, school board members, parents, and taxpayers are able to ask informed questions so that they can determine whether this new investment will be worthwhile.

Where has the money gone?

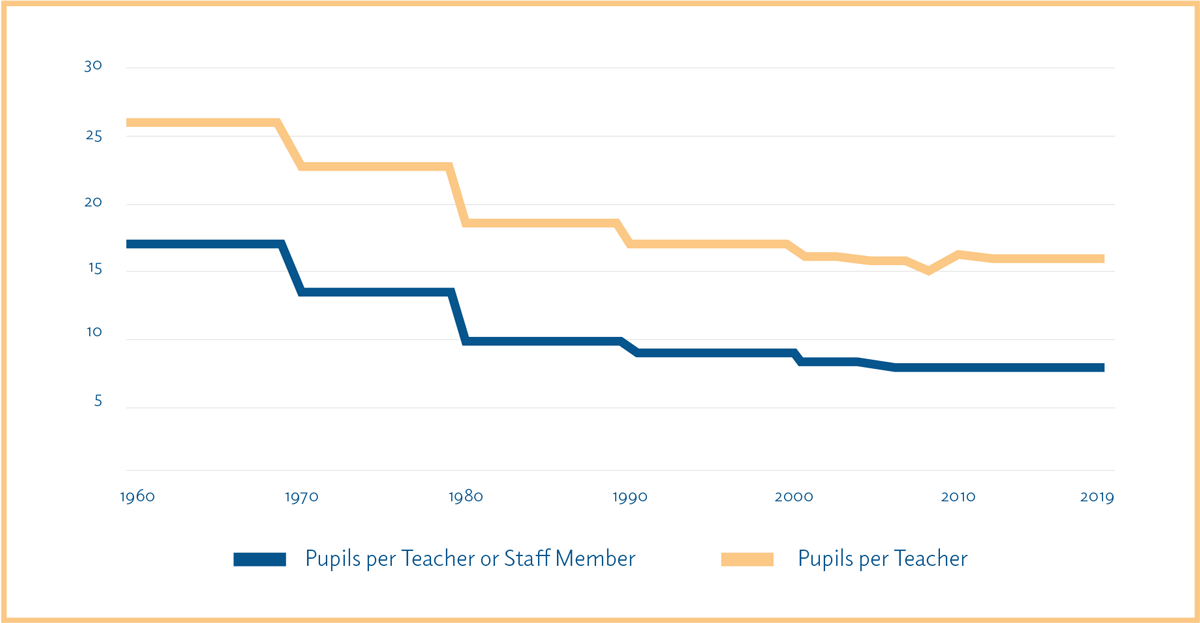

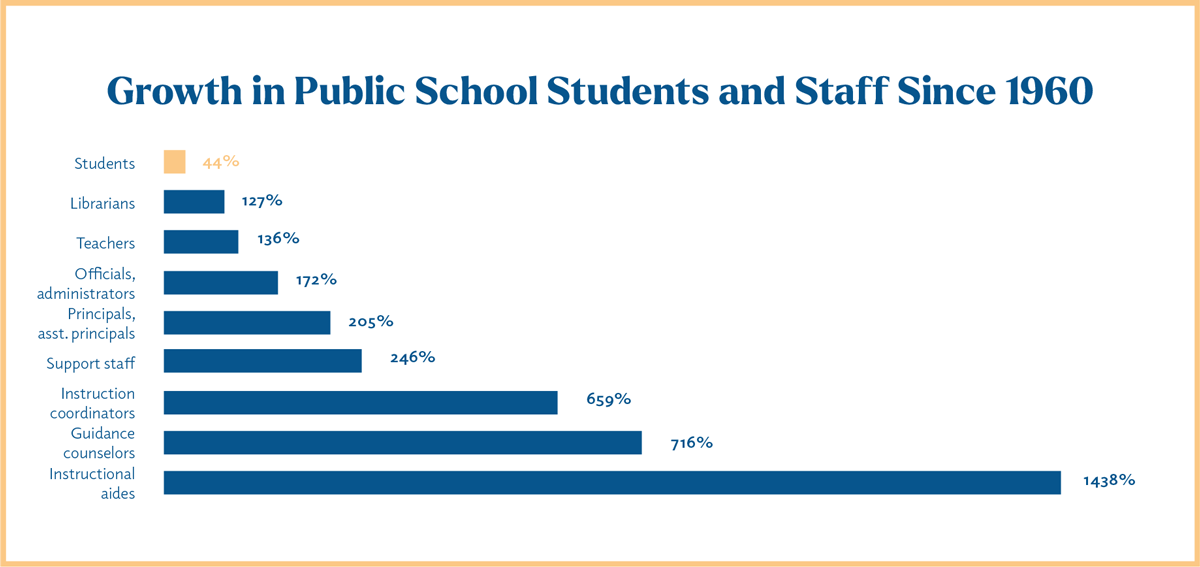

The overwhelming proportion of schools’ general funds—more than 80 percent—are spent on salaries and benefits, and so staffing growth is inextricably tied to spending growth.5 While public school enrollment has increased only 44 percent since 1960, the number of teachers has increased 136 percent, leading to a decline in student-to-teacher ratios, from about 26 students per teacher to about 16 students per teacher.6 But that is far from the whole story. During this same period, the number of other, non-teaching staff went up by a much more significant degree, leading to far more adults in schools than ever before.7

In all, about 4.6 million additional adults have been added to schools since 1960 and only about four in 10 were teachers.8 In fact, by 2010, the proportion of all public school staff who were teachers dropped to 50 percent and has continued to fall since.9 While many large urban school districts have a deserved reputation for bloated central district offices, there are actually more non-instructional staff per student in rural areas.10

Although parents often consider the possibility of more individual attention for their children, they rarely consider whether that attention will come from a better or worse teacher than if class sizes were larger. Reducing adult-to-student ratios is popular among teachers’ unions because each additional adult is still an automatic additional dues-payer in many localities. It is also popular among rank-and-file teachers because, theoretically, at least, it means more hands to do the work.

Despite research to the contrary, one survey found that 90 percent of teachers believed that smaller class sizes have a “strong” or “very strong impact on improving student achievement.”11 In fact, respected economic researchers Danielle Handel and Eric Hanushek found that “a 10 percent reduction in class size would, at the median estimate, yield less than 0.01 [standard deviation] increase in student achievement,” and concluded that funds are likely best spent elsewhere.12

A possible reason for the disconnect between well-intentioned policies and real-world results is that to reduce class sizes, new teachers must be recruited to join the ranks. New entrants to the profession may not be as strong as veterans due to experience or because the best candidates tend to get selected for open positions first. One study explored this idea further and found that academic gains could be realized by adding more students to the classrooms of the very best teachers and giving less responsibility to (or letting go) the teachers with student outcomes that didn’t meet higher standards.13

Giving additional responsibility to high performers is common sense in nearly any other profession but is seldom utilized in this way in our schools. If teachers are paid based on their total value add to students and their peers, one could imagine the very best teachers earning considerably more than even highly compensated teachers today.

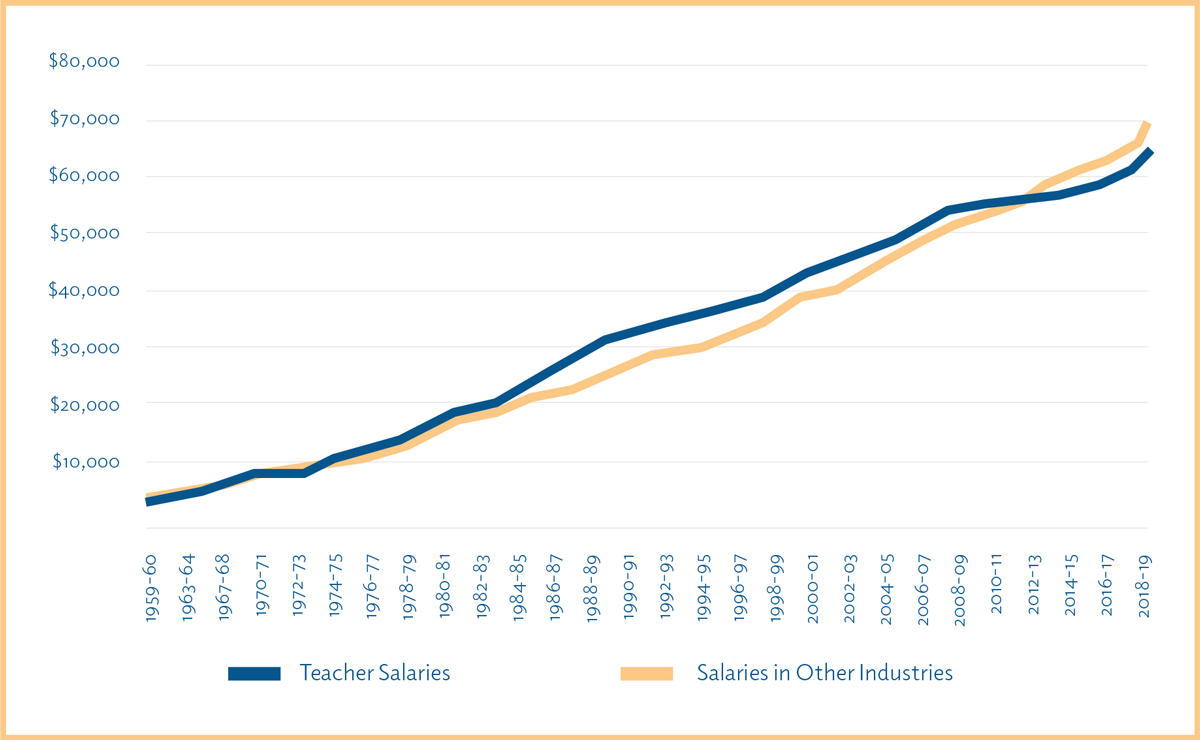

The other major challenge is that, when school systems add many more adults to each school and keep class sizes low, it is more difficult to pay them all substantially more. This is the case despite significant overall increases in school spending. As a result, teacher pay in real terms has been remarkably flat for decades, and they make less today than they were nearly 40 years ago (in real terms). This contributes to the well-publicized difficulties many schools are having in recruiting new teachers. While teachers have generally made a bit more than workers in other industries historically, the two groups hit parity in 2012-13, and teacher incomes have continued to fall further behind ever since.14

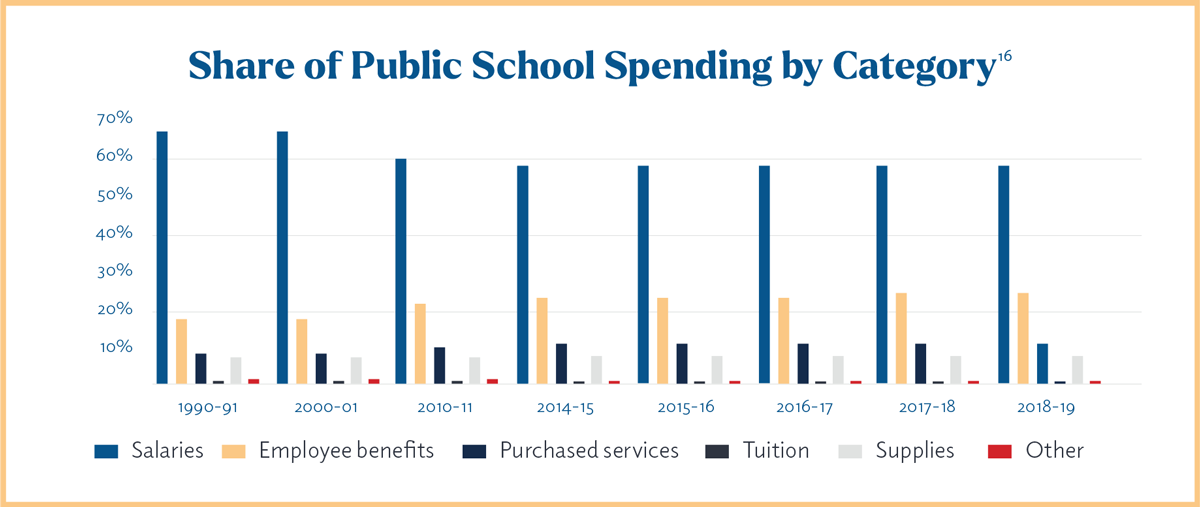

One important caveat, however, is that total compensation is often not accounted for. In fact, a surprisingly large proportion of funds are going to teachers and staff in the form of benefits (17% in 1990-91 vs. 24% in 2018-19) rather than salary (66% in 1990-91 vs. 55% in 2018-19). According to a Reason Foundation study, “Between 2002 and 2020 total education spending on employee benefits (such as pensions and healthcare) in the U.S. nearly doubled from $90 billion to $164 billion a year.”15

One option is to simply support parents in choosing the school that most efficiently and effectively allocates resources to best serve their children. For some families this could be added special needs programs while others desire stronger STEM or arts programs.

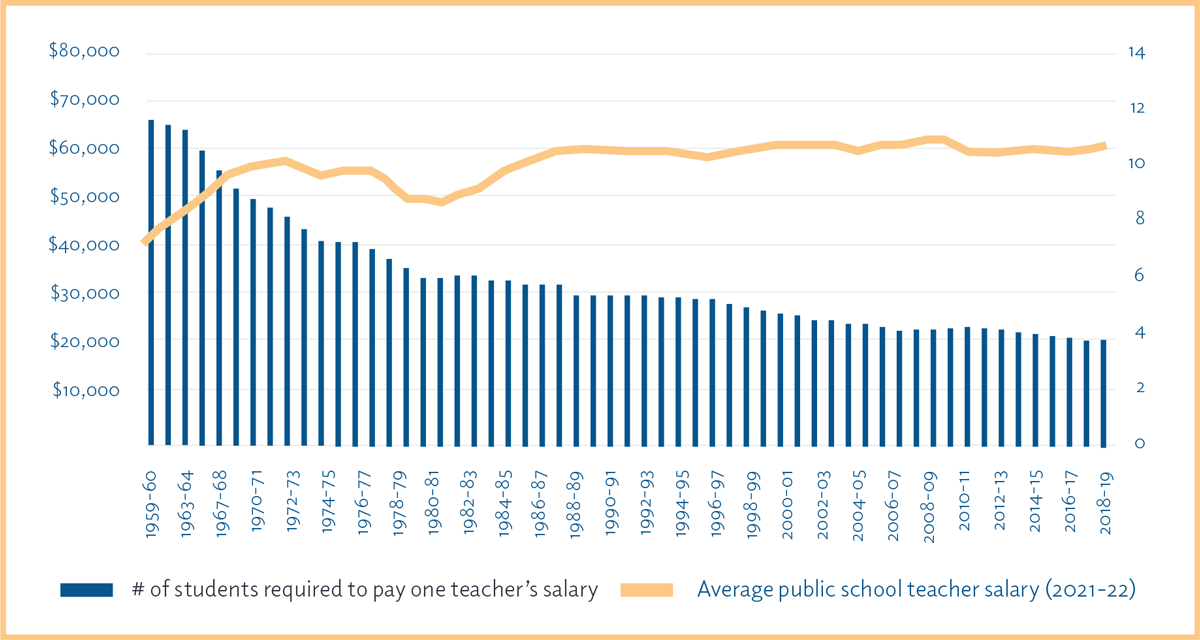

Inefficiency and ineffectiveness in government-operated schools simply cannot be ignored, even where school choice is prevalent. The reality is that the same system, which is not working for many public-school children is also not working particularly well for teachers either. As the chart below shows, a classroom teacher today is capturing far less of the funds than his or her students bring with them.

School districts often balk at increasing salaries in union negotiations since the increases would strain budgets immediately. Instead, they get trapped by demands for more benefits, including keeping up with the rising cost of health insurance and bigger pensions. Pension benefits can be an attractive way for school leaders to give a bit in negotiations because the effect of being more generous will be someone else’s problem decades into the future. The fact that decades of funding increases have been pumped into paying non-teaching staff and covering the hidden cost of benefits for current and legacy employees have left veteran teachers with the same number of students and papers to grade as they did when they started teaching but without being better off financially despite many years on the job. In any other profession, workers would quit and move to a new company. But what is a public schoolteacher to do? Quitting and moving to another school would not solve their problem.

Do we know how to spend smarter?

If the way we have been spending our educational dollars has failed to translate into gains in educational achievement, we might wonder whether a different approach might work. Naturally, of course, all the discussion so far has been about national averages. There are differences in how states and local schools spend and differences in their educational achievement, which in many cases have moved dramatically up or down over the decades. There are lessons to be learned from these examples, and it would be a mistake to assume that there are no levers to pull simply because the national picture looks basically like a wash. Unfortunately, many of the most common suggestions to promote improvement come up empty.

The Handel and Hanushek research mentioned previously not only looked at class size but also explored many other recipes for budget-driven academic excellence. They found some positive effects from increased capital expenditures but not enough clear insights to draw conclusions, except that funds should be spent wisely there, too. Nicer facilities can be helpful in many ways, but they do not necessarily translate into better student achievement, as some have hypothesized. By contrast, there is hope that performance pay for teachers could drive improvement, but we are still not exactly sure how to design such systems and so more room for innovation is needed.17

In all, the pair conclude, “simply adding more resources without addressing how and where the resources will be used provides little assurance that student achievement will improve. Little progress has been made leveraging the results to uncover when more spending will have significant impacts and when it will not.”18 If we know that spending matters somewhat and spending on the “right” things matter a lot, but we do not have significant clarity on what those “right” things are, what are policymakers to do?

The 65% Solution

In the early 2000s, a group called First Class Education proposed that states require 65 percent of funds be spent “in the classroom,” which they defined as things such as classroom teachers and instructional supplies, but not administrators or food service.19 This seemed like common sense, and the plan quickly received the support of many, mostly conservative governors and state legislators, as well as commentators such as George Will, who praised the idea because it would ensure that more funds were spent on “teachers and pupils, not bureaucracy.”20

The solution generated skepticism, unsurprisingly, from education establishment groups but also from conservative reformers like the American Enterprise Institute’s Rick Hess, who recognized that the idea “focuses attention on dubious input measures and is an invitation to creative accounting. Most troubling, though, is the manner in which it embraces heavy-handed, autocratic management—under the guise of ‘decentralization’ — and endorses one-size-fits-all guidelines.”21 Others noted that “the salaries of athletic coaches and uniforms count as in-the-classroom instruction, but the salaries of librarians and guidance counselors do not.”22 Even George Will conceded, “there is scant evidence that increasing financial inputs will, by itself, increase a school’s cognitive outputs.”23

Still, many states explored the idea in the early 2000s. Florida Governor Jeb Bush pushed a constitutional amendment in Florida,24—Texas Governor Rick Perry, Minnesota Governor Tim Pawlenty, and other state leaders at the time supported it too.25 Due to a variety of factors, including political pushback, difficulty coming up with a uniform measure of “classroom” spending, the fact that ballot initiatives would have been required in some states, and the wide opportunity for gaming the system, these plans each fizzled. While at first glance, simple metrics can seem like an easy way to hold the system accountable, reformers have found that driving improvement instead requires a multi-faceted approach.

Considerations for Policymakers

One way to determine if it is possible for schools to spend more efficiently is to see whether similarly situated schools and students achieve similar outcomes with different levels of funding. In fact, many school choice programs have illuminated this very question. Voucher schools, for example, often cost less than their public-school counterparts (sometimes due to political compromises) and generally get better results.26-27 Evaluations of charter schools have also validated their cost effectiveness.28

While school choice programs—and the market forces they employ—are likely the most effective solution yet devised for getting more educational improvement per dollar, other solutions are needed too. Most students still attend traditional public schools. This demands that state policymakers consider a comprehensive approach made up of a variety of policy solutions.

- First, do no harm. Schools that are getting results on objective measures of student progress, especially schools with high proportions of students starting out with deficits, should be left alone if not rewarded. They should maintain maximum flexibility to innovate and respond to critical needs. Some states, like Indiana, have created a formal system of waivers to remove hindrances as local schools try to innovate to improve educational outcomes.29

- Promote transparency. School boards, superintendents, and principals, not state bureaucrats, are best positioned to ensure each dollar is used wisely. This is especially critical as schools approach their September 2024 deadline for spending nearly $200 billion in one-time COVID relief funds. So far, many have had challenges finding any use for these funds, much less a productive one.30 It is a concerning sign that many public school leaders are referring to a “fiscal cliff,” implying that they view the absence of these funds as a “cut” rather than their allocation as a boon, especially when they are struggling to find ways to spend the additional funding in the first place.

Much of these funds have still not been spent, and an untold amount will be spent unwisely and on things wholly unrelated to pandemic response or learning loss recovery.31 While states and districts have been hindered by the reality that most of their budget goes to staff and a closing window on one-time funds could result in layoffs, they must ensure any reduction in staff (or other spending) is done based on data-driven analyses of what works rather than other factors like staff seniority, program popularity, or gut feelings.

These leaders can make more informed decisions by ensuring uniform spending data collection and reporting it in a way that is easy for parents, school board members, and others to put to good use. As education finance guru Marguerite Roza has noted, “the unit of the district [is] too large and clunky to provide useful comparisons,” and so information is needed that looks at each school building.32 Michigan, for example, provides granular details about local school spending through a public portal.33 At OhioCheckbook.com, users can see payments at the transaction level, detailing everything from each time the school orders milk to major bus repairs.34

While states should generally stay out of decision-making at this level, they can require the transparency necessary to empower better local decision-making. States could further promote transparency by setting and enforcing standardized accounting practices so that spending decisions could be better compared and understood by state officials and the public. They also must not be shy about demanding—and utilizing—the power to investigate fraud and intervene when poor decision-making reaches the level of misconduct.

- Ensure existing staff are used wisely. School districts must also make the best possible use of existing staff before further expanding employment. They should not be expected to come up with these staffing models alone, though. State departments of education should highlight proven examples whenever possible.

For example, they might explore how to better employ reading and other specialists to tackle deficits most efficiently before they become larger issues. Teacher career ladders that follow the research should also be explored. With more adults in the classroom than ever before, not all classroom teachers need to be doing the same thing they always have. The very best teachers should be freed from as much drudgery as possible so that they can focus on making as many of their students—and fellow teachers—better.

All of this, however, assumes that local school officials are empowered to make such decisions and are accountable when they do not. Union politics consistently corrupts this bargain with taxpayers and voters. In their evaluation of school spending, Handel and Hanushek noted that, “It appears very likely that restrictions from unionized bargaining and contracts interact significantly with resource decisions.”35

If local school leaders cannot make decisions about who to hire and fire or how to utilize staff most effectively, and school board races are dominated by union money, there is little hope for that school to improve on its own. States must ensure that union membership is voluntary only and that local officials are empowered to run day-to-day operations without seeking the union’s permission.

- Remove non-teaching positions that do not contribute to a school’s mission. With the explosive growth in public school staff, there are naturally going to be positions at some schools that do not contribute to what a school is supposed to be doing, namely, educating students. Some of this is outright waste, including family members of school leaders hired as consultants, warehousing of teachers that cannot be fired at the district central office, and other examples of corruption that have become far too commonplace.

There are other examples, too, though, of positions that are just not worth the total cost of compensation. Spending on political rather than academic priorities must be curbed. While transparency is an essential starting point, staff members mostly or entirely devoted to political goals or abstract or non-academic missions that cannot be measured must be prohibited, including by state lawmakers, if needed.

The Heritage Foundation examined 554 districts with enrollment above 22.5 million—representing roughly 44 percent of all public-school students—and found that 39 percent employed a chief diversity officer.36 This number was 82 percent in Illinois but only 16 percent in Texas. This number has likely continued to grow since publication in 2021, even in the face of parental backlash, and there should thus be greater scrutiny as to whether these often highly paid officials are working toward measurable goals that benefit students.

- Empower local leaders to make better decisions. Local officials cannot act on good data, however, if they do not know how to interpret it. There are more than 82,000 local school board members in the United States.37 Many of them lack budgetary experience beyond their family’s budget and have not previously managed large, complex organizations. They may lack knowledge of which curriculum to purchase and how much flexibility state law or the union contract provides.

States should mandate training for all local school board members, principals, and superintendents on how to understand, interrogate, and improve a district’s finances. These leaders also require a better understanding of student outcomes, including what “good” test scores look like and how those test scores might be influenced by demographics and other factors. They should be required to take training on these topics too that is as research-based.

Regardless of whether a given school’s students are highly advantaged or not, local leaders must learn to determine whether students know significantly more at the end of the year than at the beginning. Evaluating success depends heavily on being able to measure it. Many states still test their students once per year and only receive results weeks or months later when they provide little useful information to parents, teachers, and administrators. To make matters worse, cut scores on these tests remain depressingly low. All states should enact policies that make it less cumbersome for schools, less stressful for students, and more useful for parents and teachers.

This is most crucial for reading. While some may balk at any kind of assessment for children in early grades, reading is the most fundamental academic skill and should be treated as such. That means instantaneous and evidence-based interventions when a child is struggling to read. Research here is far more solid than in most other areas of education. Where gaps and failure persist, there must be swift and certain intervention from district leaders to replace or retrain educators, many of whom may have received very poor training, tools, and strategies from their teacher preparation program. One study found that “only 25% of programs adequately cover all five core components of scientifically based reading instruction.”38

District leaders must also be given the tools they need to shop for curriculum and professional development that is proven to work, especially in early reading skills, where the stakes are highest, and the research base is most solid. A growing number of states are now requiring that curriculum and professional development be tied to the “science of reading.” They intervene assertively and hold students back a year when necessary. These states have seen outstanding results and other states should work to understand why and emulate their success.39

- Promote commonsense mechanisms to reach economies of scale. The median school district in America has well under 1,000 students.40 Smaller and more rural schools need flexibility to share resources, but many states make that difficult. State law should clearly empower any district to work with any other to jointly contract for services and hire administrators. Districts that overspend on administration could potentially be mandated by states to join and participate in these contracting consortia, while avoiding more politically fraught consolidations. These steps can move more functions to the county or regional level to cut down on duplicative contracts, administrators, capital expenditures, and more.

A Fordham Institute report found that sharing administrators could save Ohio’s smallest school districts up to $40 million per year. One example they highlighted was especially promising. The Rittman and Orrville districts “share an assistant superintendent, treasurer, director of operations, special education director, EMIS coordinator, and a transportation support team. The districts also share the time of a French teacher and special services for emotionally disturbed and multi-handicapped students.” In one year, the arrangement has produced a savings of about “$270,000—$170,000 for Orrville and $100,000 for Rittman.”41

- Parental empowerment is the ultimate form of local control. States should avoid giving bureaucrats the ability to run an entire state’s schools from the capital and instead vest control in local districts. However, the extent to which districts determine outcomes should be limited in scope. Ultimately, parents should have the final say in what or how their children are taught. And sometimes, this means exercising school choice options.

School choice is often criticized as a political mechanism of the Right, but it is vital when it comes to holding local school districts accountable—and giving parents an escape route when they have had enough. This is especially true for parents lacking the financial means to move to a better district or pay for private school. University of Arkansas researcher Patrick Wolf studied the issue and found that “more education freedom is significantly associated with increased NAEP (National Assessment of Educational Progress) scores and gains, supporting the claim that choice and competition improve system-wide achievement.”42

States should enact parental choice policies that allow families a different option, especially if their assigned public schools are not serving them effectively. But choice—at least among public district and charter options—should be the default as in some localities like Washington, DC. And parents should be given micro-level choices too. It is overly simplistic to declare an entire district or school a “success” or a “failure.”

Even great schools can usually only hope to meet the needs of most students most of the time. However, they may not offer an alternative to a course that is not working for an individual child, and they cannot be expected to offer every foreign language, computer science, or career-focused course any parent may desire. In fact, attempts to meet even quite justified one-off needs like this can quickly contribute to a school’s overall inability to cost-effectively meet most of the needs of most children.

That is why parents should also be given course-level choice so that they can opt out of an offering they dislike or opt into something their school does not offer. Many states have passed such policies as a way to expand course offerings while relieving pressure on district leaders, serving gifted children, and preparing students for college or work prior to graduation.43

Conclusion

These solutions can improve outcomes for children while boosting value to taxpayers, but only when adopted with fidelity by strong local leadership. Policies that seem like a remedy in one district or region may fail in others. Despite the political risks of intervention, however, state leaders should not view these realities as an excuse for an entirely hands-off approach. No matter the strategy, when it persistently fails children, states have a responsibility to intervene with a combination of incentives and accountability measures to encourage or, if needed, require changes.

While states employed tough rhetoric over the years to pass comprehensive accountability laws, most ultimately lacked the political courage to employ the toughest sanctions. Instead, states brought in consultants and shuffled around staff because it was too difficult to fire low performers.

A persistent lack of results and poor use of funds often demand new leadership with a fresh approach. States could consider requiring local districts with poor academics and high spending on administration to obtain state permission to further expand non-academic staff. Not all states will be comfortable with this level of state oversight, however, and not all states have the necessary capacity at their state departments of education to properly oversee these staffing needs.

Parental empowerment can also serve as an effective state-level intervention. Students in low-performing, low-efficiency districts could be offered enrollment in a neighboring district or charter school or given a voucher or education savings account with their share of state funds. The remaining public schools could be managed by outside charter school operators as in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. States could also band together to create a larger market for these services and the benefits scale could bring to the overall system.

For conventional districts, states could also guide or direct the district’s major spending and staffing decisions, lease unused facilities to schools with growing enrollment, and manage pension and other obligations, particularly if the district becomes financially unstable due to large numbers of exiting students.

Ultimately, there is no clear recipe for turning financial inputs into student outcomes. What we do know is that to be successful, states will have to empower local schools and hold them accountable for results, while ensuring that true local control rests ultimately with families. Each local district cannot be expected to find and implement best practices alone and may need state support to improve, including through better and more actionable academic and financial data, the ability to utilize economies of scale, and direct guidance to ensure that failed academic approaches are weeded out.

State leaders will need to eschew quick fixes or overly simplistic measures and embrace flexible accountability that will sometimes require local autonomy and other times demand a firm hand. Financial levers are a vital and often ignored aspect of the success of our schools, however, policymakers must approach them with care and an understanding that neither budget levels nor their allocations necessarily equate to academic destiny.

References

- “Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965.” Ballotpedia. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://ballotpedia.org/Elementary_and_Secondary_Education_Act_of_1965.

- “Digest of Education Statistics, 2022.” National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Home Page, a part of the U.S. Department of Education. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d22/tables/dt22_236.55.asp.

- “NAEP Report Card: Reading.” The Nation’s Report Card. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/reading/nation/scores/?grade.

- The big bet on adding staff to improve schools is breaking the bank. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://edunomicslab.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/roza_webreadypdf_revised.pdf.

- “Digest of Education Statistics, 2021.” National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) , a part of the U.S. Department of Education. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d21/tables/dt21_236.20.asp.

- “Digest of Education Statistics, 2021.” National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) , a part of the U.S. Department of Education. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d21/tables/dt21_213.10.asp.

- “Digest of Education Statistics, 2021,” National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Home Page, a part of the U.S. Department of Education, accessed December 5, 2023, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d21/tables/dt21_213.10.asp.

- “Digest of Education Statistics, 2021,” National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Home Page, a part of the U.S. Department of Education, accessed December 5, 2023, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d21/tables/dt21_213.10.asp.

- “Digest of Education Statistics, 2021,” National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Home Page, a part of the U.S. Department of Education, accessed December 5, 2023, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d21/tables/dt21_213.10.asp.

- Farkas, Steve, Nathan Levenson, and Dara Zeehandelaar Shaw. “The Hidden Half: School Employees Who Don’t Teach.” The Thomas B. Fordham Institute. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/research/hidden-half-school-employees-who-dont-teach.

- Primary sources 2011 – scholastic. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.scholastic.com/primarysources/pdfs/Gates_FullDraftR11TOVIEW.pdf.

- The impact of COVID-19 on small business owners: National bureau … – NBER. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27309/w27309.pdf.

- Richmond, Matt, and Victoria McDougald. “Right-Sizing the Classroom: Making the Most of Great Teachers.” The Thomas B. Fordham Institute, December 8, 2014. https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/research/right-sizing-classroom-making-most-great-teachers.

- “Digest of Education Statistics, 2022.” National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Home Page, a part of the U.S. Department of Education. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d22/tables/dt22_211.50.asp.

- Smith, Aaron Garth. “K-12 Education Spending Spotlight: An in-Depth Look at School Finance Data and Trends.” Reason Foundation, January 12, 2023. https://reason.org/commentary/k-12-education-spending-spotlight/.

- “Digest of Education Statistics, 2021.” National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) , a part of the U.S. Department of Education. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d21/tables/dt21_236.20.asp.

- The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and policy responses on … – NBER. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28930/w28930.pdf.

- The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and policy responses on … – NBER. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28930/w28930.pdf.

- Bracey, Gerald W. “A Policy Maker’s Guide to ‘the 65% Solution’ Proposals.” National Education Policy Center, January 1, 2006. https://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/a-policy-makers-guide-the-65-solution-proposals.

- Will, George F. “Improving the State of Education by 65 Percent.” Tampa Bay Times, December 11, 2019. https://www.tampabay.com/archive/2005/04/10/improving-the-state-of-education-by-65-percent/.

- “The 65 Percent Solution.” The Washington Times, February 21, 2006. https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2006/feb/21/20060221-091158-1703r/.

- Bracey, Gerald W. “A Policy Maker’s Guide to ‘the 65% Solution’ Proposals.” National Education Policy Center, January 1, 2006. https://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/a-policy-makers-guide-the-65-solution-proposals.

- Will, George F. “Improving the State of Education by 65 Percent.” Tampa Bay Times, December 11, 2019. https://www.tampabay.com/archive/2005/04/10/improving-the-state-of-education-by-65-percent/.

- Petersburg, St. “‘65% Solution’ Aims to Dissolve Class-Size Rule.” Gainesville Sun, December 29, 2005. https://www.gainesville.com/story/news/2005/12/29/65-solution-aims-to-dissolve-class-size-rule/31470449007/.

- “The Academic Effects of Private School Choice: Summary of Final Year Results from Experimental Studies.” School Choice Demonstration Project. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://scdp.uark.edu/the-academic-effects-of-private-school-choice-summary-of-final-year-results-from-experimental-studies/.

- “The Academic Effects of Private School Choice: Summary of Final Year Results from Experimental Studies.” School Choice Demonstration Project. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://scdp.uark.edu/the-academic-effects-of-private-school-choice-summary-of-final-year-results-from-experimental-studies/.

- “New Analysis Finds Choice Schools More Cost-Effective than Public School Peers.” School Choice Wisconsin, August 30, 2023. https://schoolchoicewi.org/new-analysis-finds-choice-schools-more-cost-effective-than-public-school-peers/.

- “Making It Count: The Productivity of Public Charter Schools in Seven U.S. Cities.” School Choice Demonstration Project. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://scdp.uark.edu/making-it-count-the-productivity-of-public-charter-schools-in-seven-u-s-cities/.

- In.gov | the official website of the State of Indiana. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.in.gov/sboe/files/IN-Flex-Guide-12182020.pdf.

- “Billions in School Covid-Relief Funds Remain Unspent.” The Wall Street Journal, May 18, 2022. https://www.wsj.com/articles/school-districts-are-struggling-to-spend-emergency-covid-19-funds-11652866201.

- “Esser Expenditure Dashboard.” Edunomics Lab, November 28, 2023. https://edunomicslab.org/esser-spending/.

- “Funds by function.” MI School Data. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.mischooldata.org/funds-by-function/.

- “School Districts.” Ohio Checkbook – Local Schools List. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://checkbook.ohio.gov/Local/SchoolsList.aspx.

- “School Districts.” Ohio Checkbook – Local Schools List. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://checkbook.ohio.gov/Local/SchoolsList.aspx.

- The impact of covid-19 on small business owners: National bureau … – NBER. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27309/w27309.pdf.

- Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on K-12 education: A systematic … – eric. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1308731.pdf.

- “New Data Finds Major Gaps in Science of Reading Education for Future Elementary Teachers.” National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ). Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.nctq.org/publications/New-Data-Finds-Major-Gaps-in-Science-of-Reading-Education-for-Future-Elementary-Teachers.

- “New Data Finds Major Gaps in Science of Reading Education for Future Elementary Teachers.” National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ). Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.nctq.org/publications/New-Data-Finds-Major-Gaps-in-Science-of-Reading-Education-for-Future-Elementary-Teachers.

- Lurye, Sharon. “‘Mississippi Miracle’: Kids’ Reading Scores Have Soared in Deep South States.” AP News, October 11, 2023. https://apnews.com/article/reading-scores-phonics-mississippi-alabama-louisiana-5bdd5d6ff719b23faa37db2fb95d5004.

- Elementary and secondary information system. Accessed December 5, 2023. http://nces.ed.gov/ccd/elsi/.

- Lafferty, Mike. “Collaboration Could Save Small Districts Big Bucks.” The Thomas B. Fordham Institute. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/commentary/collaboration-could-save-small-districts-big-bucks.

- “Education Freedom and Student Achievement: Is more school …” Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15582159.2023.2183450.

- Emerson, Adam, Priscilla Wohlstetter, and David Figlio. “Expanding the Education Universe: A Fifty-State Strategy forCourse Choice.” The Thomas B. Fordham Institute, August 1, 2014. https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/research/expanding-education-universe-fifty-state-strategy-course-choice.

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about our fight for policies at the state level that restore liberty through transparency and accountability in American governance.