Toward Pharmacist Full Practice Authority

Background and Problem

More than 30 percent of Americans don’t have a primary healthcare provider, and those who do often face long wait times to get an appointment with a physician experiencing burnout.1–2 The dire situation leaves patients the choice to either forgo care altogether or make do with higher-cost urgent care and emergency room visits. While the physician and primary care provider shortage compounds, the United States healthcare system is sidelining 330,000 doctorate-trained (PharmD) pharmacists who are qualified to provide many medical services.3

Pharmacists are poised to solve primary care shortages, diagnose and manage chronic diseases and minor ailments, decrease unnecessary emergency room visits, and deliver preventative health outcomes. Beyond the practical application of skills, pharmacists are consistently ranked by patients as trusted licensed healthcare providers for honesty and high ethical standards.4

Nearly 90 percent of Americans live within five miles of a community pharmacy, with urban Americans in a two-mile radius of pharmacy services.5 The weekend hours and evening accessibility make pharmacists one of the most accessible healthcare providers. This is especially true in rural and underserved urban communities, where the local pharmacy often serves as a central pillar of healthcare. Giving pharmacists the ability to deploy the full scope of their training and experience is a safe and effective way to alleviate the pressure of doctor shortages.

Pharmacist Education and Training as Healthcare Providers

Pharmacist education and training standards are consistent across all states requiring prospective pharmacists to graduate from a Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) program accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmaceutical Education (ACPE) and pass the North American Pharmacist Licensure Examination (NAPLEX) to demonstrate clinical competence.6 The US Department of Education recognizes ACPE as the national agency for the accreditation of professional degree programs and education standards in pharmacy.7 Pharmacists receive four years of post-graduate education that includes 1,740 hours of clinical patient care training in all practice settings. All of that is commonly preceded by the four years it typically takes to earn a bachelor’s degree. Comparatively, advanced practice registered nurses (APRN) who have been ascended to full practice authority in more than 35 states, complete a doctorate-level education with 750 hours of clinical patient training.8

The decades of ACPE standards surrounding diagnosis and prescribing were concisely articulated in the PPCP issued by the Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners (JCPP).9 The ACPE 2016 Standards adopted the PPCP establishing consistency in pharmacist education across all practice settings on differential diagnosis and prescribing consists of five steps:

- Collecting subjective and objective patient information

- Assessing the information collected and analyzing the clinical effects of the patient’s therapy

- Developing an individualized patient-centered plan that is evidence-based and cost-effective

- Implementing and documenting the care plan

- Patient follow-up to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of the care plan10

The forthcoming ACPE 2025 Standards continue the curriculum trend towards codification of independent practice for patient screening, the performance of tests and assessments, diagnosis, drug administration, evidence-based clinical decision-making, therapeutic treatment planning, and prescribing.11

The intersection between ACPE accreditation standards, the Pharmacists’ Patient Care Process (PPCP), and impeding state laws on pharmacists full practice authority is nicely summarized by Adams and Weaver: “For pharmacists to fully engage in the Pharmacists’ Patient Care Process, state laws must enable full participation. Unleashing pharmacists to fully engage in the process can improve patient care delivery and reduce total healthcare costs.”12

Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) – Standards 2025

Required Elements of the Didactic Doctor of Pharmacy Curriculum

Clinical Laboratory Data

Application of clinical laboratory data to disease state management, including screening, diagnosis, progression, and treatment evaluation.

Medication Prescribing, Preparation, Distribution, Dispensing, and Administration

Prescribing, preparing, distributing, dispensing, and administering medications including, but not limited to: injectable medications, identification and prevention of medication errors and interactions, maintaining and using patient profile systems, prescription processing technology and/or equipment including oversight of support personnel, and ensuring patient safety. Educating about appropriate medication use and administration for various disease states including substance use disorder. All students must receive training in immunizations.

Patient Assessment

Evaluation of patient function and dysfunction through the performance of tests and assessments leading to objective (e.g., physical assessment, health screening, and lab data interpretation) and subjective (patient interview) data important to the diagnosis and provision of care.

Pharmacotherapy

Evidence-based clinical decision making, therapeutic treatment planning (including diagnosing and prescribing), and medication therapy management strategy development for patients with specific diseases and conditions that complicate care and/or put patients at high risk for adverse events. Emphasis on patient safety, clinical efficacy, pharmacogenomic and pharmacoeconomic considerations, and treatment of patients across the lifespan.

Self-Care Pharmacotherapy

Therapeutic needs assessment, including the need for triage to other health professionals, drug product recommendation/selection, diagnosis, prescribing, and counseling of patients on non-prescription drug products, non-pharmacologic treatments, and health and wellness strategies, including nutraceuticals.

Empower Pharmacists to Diagnose and Prescribe

Joffe and Singer articulate a compelling history of the decades of jurisdictional success of independent pharmacist diagnosis and prescribing in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and the United States where peer-reviewed literature ensconces a robust body of evidence of patient acceptance, patient demand, and patient safety profile.13 Opposition to scope of practice reform relying on emotional anecdotes will be hard-pressed to find evidence-based literature showing inferiority or legitimate patient safety outcomes of pharmacist diagnosis and prescribing care.

Tsyuki and colleagues have published multiple randomized controlled trials [RxEeach, RxACT, RxACTION, RxING] with statistically significant results demonstrating pharmacist care to be superior to usual physician care when independently prescribing and managing for cardiovascular disease (CVD)—hypertension, hyperlipidemia, tobacco cessation, and diabetes mellitus.14,15,16,17 Dixon and colleagues published in the Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA), that the cost-effectiveness of implementing a pharmacist-prescribing intervention to improve blood pressure control in the United States at 50 percent intervention uptake was associated with $1.137 trillion in cost savings and would save an estimated 30.2 million life years over 30 years.18

Akers and colleagues demonstrate that pharmacists treating minor ailments at a community pharmacy lowers the median cost of care by $277.78 when compared to urgent care and emergency room visits, showing superiority to traditional care sites.19 Sammon and colleagues research from the Henry Ford Vattikuti Urology Institute demonstrates patients avoiding the emergency room for urinary tract infections (UTI) alone would save up to $4 billion dollars annually.20 Beahm and colleagues shows pharmacist prescribing and management of uncomplicated UTI is effective, safe, and patient satisfaction is high.21 The economic impact on UTIs is one example of the more than thirty minor ailment conditions pharmacists are trained to treat.22

Solution to Overregulating Clinical Services: Implement Standard of Care

Why can’t patients skip the doctor’s office altogether and simply rely on their pharmacist as the primary destination for minor healthcare? The answer is overregulation. For decades, physician protectionism masquerading as patient safety concerns has misled federal and state policymakers on scope of practice, creating a tangled web of pharmacy regulations preventing business innovation and patient choice.23 Some state legislatures and Boards of Pharmacy have relegated the role of doctorate-trained pharmacists to medication dispensaries, despite the profession having a history of taking care of patients dating back to 2100 B.C.24 Upon graduation, most pharmacists entering the healthcare marketplace are entering into a practice of regulatory captivity.

Few professionals experience heavy-handed government micromanagement and overregulation the way pharmacists do, evidenced by the hundreds of pages of pharmacy practice regulations.25–26 Surprisingly, this regulatory burden does not stem from political ideology. Texas and California each have more than 850 pages of enforceable statutes and rules governing the pharmacy practice.27–28 To the surprise of no free-market economist, the continued growth in regulation of the drug supply chain and pharmacy practice correlates to market consolidation and resource competition. Look no further than the total market share for pharmacies, wholesalers, and pharmacy benefit managers for examples.

Regulatory strings prevent pharmacists from practicing at the top of their education, training, and experience. It is long past due for the profession of pharmacy to move to a standard of care regulatory model and for states to pursue pharmacist full practice authority.

A benchmark analysis of Idaho’s healthcare regulations between 1996 and 2017 found significantly more pharmacy regulations compared with nursing and medical professions.29 Notably, pharmacy regulations contained substantially more restrictive words, with 97.5 percent and 105.8 percent higher word counts than nursing and medical regulations, respectively. Furthermore, the analysis showed pharmacy regulations were amended more frequently, underscoring a continuous need to ask governmental permission to adopt advances in educational practices, technological innovations, and evolving professional standards. The difference in Idaho’s pharmacy regulatory burden demonstrated a divergence in how other professions were regulated, showing medicine and nursing were traditionally regulated through standard of care. The states with scope of practice and provider reimbursement law that prioritize and reflect physicians as the “quarterback” of the healthcare team—and the only provider who is authorized to independently practice—are part of the problem of overregulating pharmacists.30 This is a stark difference from states that prioritize implementation of a standard of care and independent full practice authority for providers delivering patient care.

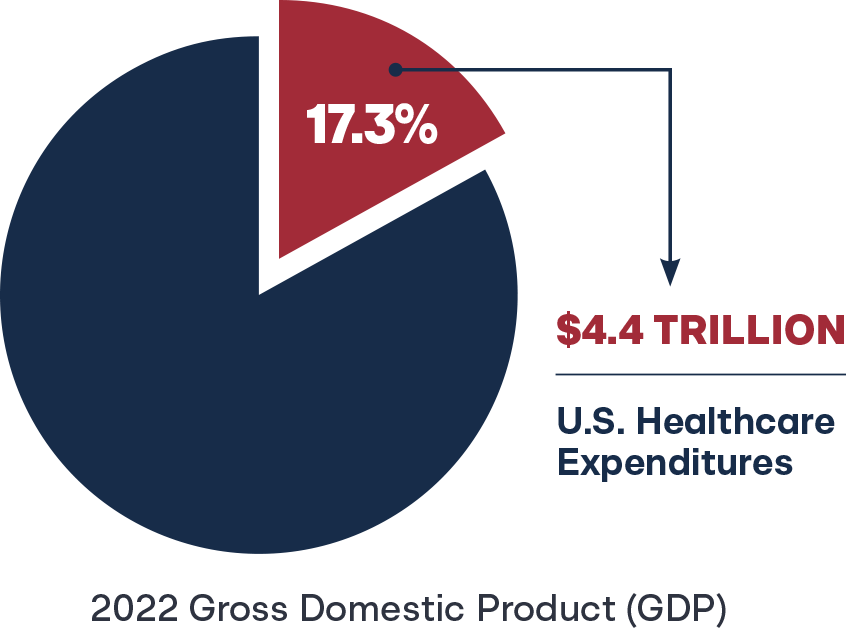

In 2022, U.S. healthcare expenditures reached $4.4 trillion, accounting for 17.3 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP), with per capita spending averaging $13,493.31 State budget officers continue to grasp at policy solutions to contain Medicaid costs, a phenomenon described as Medicaid Pac-Man, eating up precious finite dollars that could otherwise be invested in education, public safety, or infrastructure.32 Many states do not formally recognize pharmacists as reimbursable providers, and those that do often limit the recognition to narrow scope of practice allowances.33 In fairness to the insurance payor marketplace, why would they build a provider reimbursement system for services that are legally prohibited? Better yet, how can businesses and researchers test new—legally prohibited—pharmacist services and their impact on society? Simply put, overregulation of pharmacists’ scope of practice and professional autonomy leaves untapped healthcare expertise and cost-containment resources to waste across the entire healthcare system. Transitioning to standard of care and pharmacist full practice authority are potential solutions.

Defining Standard of Care

The term “standard of care” in the medical context refers to a healthcare provider acting as a reasonable and prudent provider with similar qualifications in similar circumstances and settings. Standard of care is the regulatory benchmark to measure the actions of healthcare providers and ensure they are performing their duties to prevent patient harm. If a physician, pharmacist, physician assistant, or nurse fails to meet the standard of care for their practice, the licensing board and even the courts will find the provider negligent and guilty of unprofessional conduct or malpractice for failing to meet an adequate community standard of care. The concept of standard of care in medicine and nursing was formalized in the 1980s and has continually refined over time as courts adjudicate cases.34 Since the 1980s, specialty accrediting organizations and medical practice associations have refined medical standards. New medical research and greater involvement by third-party payers like insurance companies also sped up these refinements to the standard of care.

The paramount benefit of standard of care is that standards do not come from top-down government elitist and “expert” regulators, but rather from bottom-up external market forces. A standard of care regulatory approach also follows another economic principle, perhaps best described as “permissionless innovation.”35 Providers may perform any act not directly prohibited by federal or state law by default.36 New scope of practice allowances, novel patient services, and technological advancements do not require government permission but are inherently authorized for a healthcare professional if acting according to the community standard of care.

Standard of care is different from the traditional Board of Pharmacy bright-line regulation approach of a clearly defined and objective legal standard that leaves little room for varying interpretation. Board of Pharmacy regulation has historically produced predictable and consistent results in its application by relying on specific, measurable factors that can decisively resolve legal issues.

Some government executives, particularly pharmacy inspectors, prefer it because it is easy to create a compliance “gotcha” checklist. However, bright-line regulation is a rigid application that often leads to unfair or inappropriate outcomes because it is hard to account for the complexities of individual cases. How does that impact innovation and patient choice? The profession is now entrenched across the states in a “Mother May I” form of practice, needing permission and updates to statutes and rules to perform any new patient care service or use any new technology. The best possible outcome cannot occur under the Boards of Pharmacy bright-line process to regulate licensees to the lowest common denominator. The sheer amount of regulation on the books would be impossible to surmount.

Eid and colleagues compared the total word count in statute and rule for immunization clinical services across all states for the professions of pharmacy, medicine, and nursing. Pharmacy was found to be 283 percent higher (57,425 words) than medicine (14,997 words) and 1,333 percent higher than nursing (4,006 words).37 The research highlighted the words “vaccine” and “immunization” were not even found in most states for the medicine and nursing profession, due to standard of care.

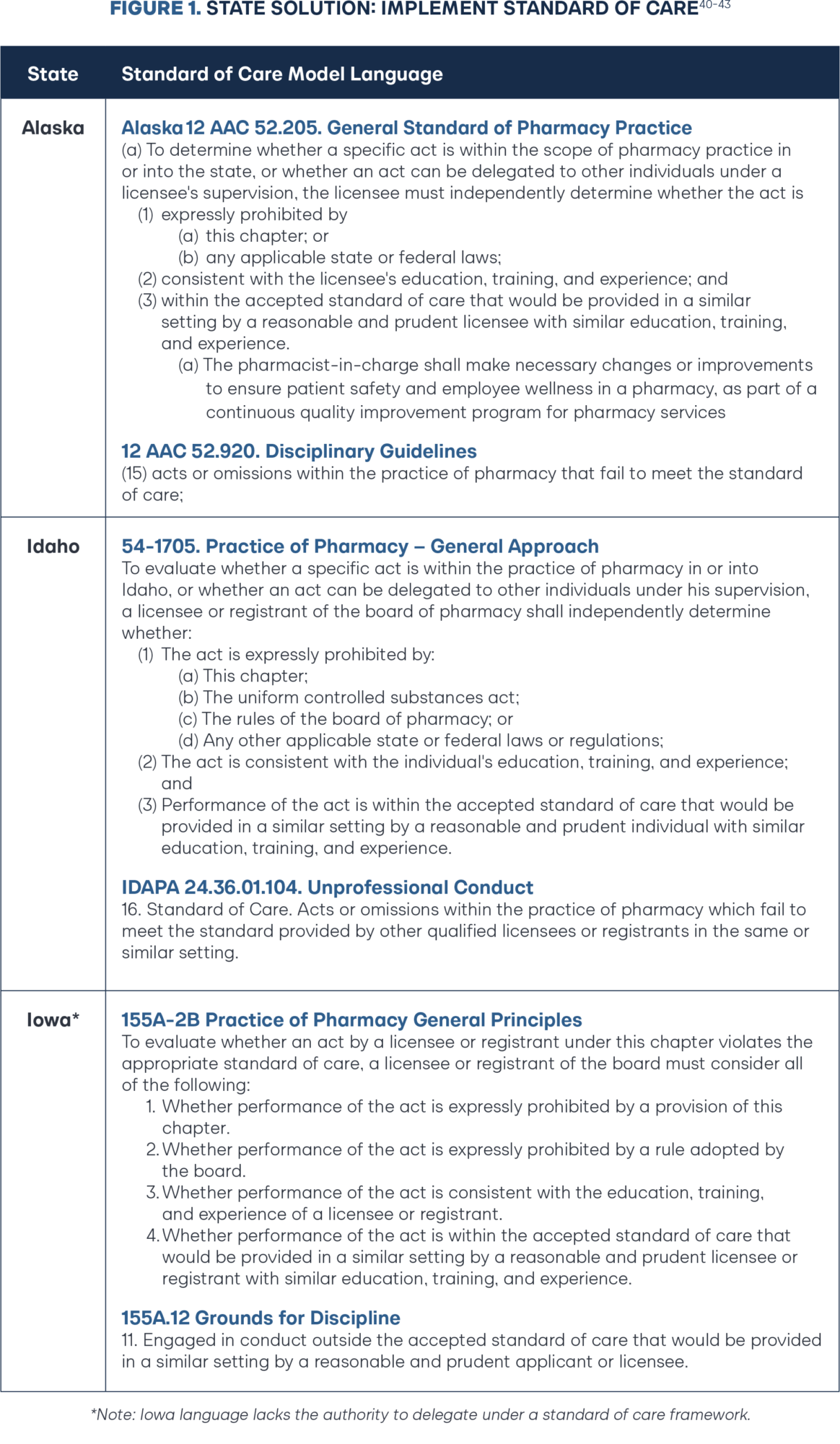

In 2017, Idaho was the first state to transition pharmacy regulation to standard of care (Figure 1).38 The decision created a cascading impact on the Board of Pharmacy. The Board reduced the regulatory volume from 125 pages to 25 pages of regulation in the last five years. More importantly, the transition included a 47.9 percent cut in the regulations governing professional practice standards and a 68.4 percent cut in the regulations governing technology. In other words, pharmacists are now authorized to innovate and given a broader scope of practice by default so long as they act within their education, training, and experience.

The Idaho Board of Pharmacy offers two questions to help licensees successfully navigate this change in approach from prescriptive, bright-line regulations to professional judgment:

- If someone asks why I made this decision, can I justify it as being consistent with good patient care and with law?

- Would this decision withstand a test of reasonableness (i.e., would another prudent pharmacist make the same decision in this situation)?39

In 2018, the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP) created a task force to develop pharmacy regulations based on standard of care.44 The task force report included the following recommendations to the profession and boards of pharmacy:

- Review the state practice act and eliminate any unnecessary regulations to recognize evolving pharmacy practice.

- Consider standard of care as a regulatory alternative for clinical care services.

- Develop a standard of care definition to include in the NABP Model Act.

In 2022, the American Pharmacist Association House of Delegates adopted the Standard of Care Regulatory Model for State Pharmacy Practice Acts model policy, requesting state boards of pharmacy and legislative bodies to regulate pharmacy practice using a standard of care regulatory model similar to other health professions’ regulatory models.45 This change allowed pharmacists to practice at the level consistent with their individual education, training, experience, and practice setting. The NABP recommendations and American Pharmacists Association (APhA) model policy combat the bureaucratic inertia and overregulation from Boards of Pharmacy, with an overdue call to action to pivot to standard of care, deregulate, and get out of the way of pharmacists to provide a higher level of care. Notably, the NABP Model Pharmacy Act has since been updated to include a definition of standard of care defined as, “the degree of care a prudent and reasonable licensee or registrant with similar education, training, and experience will exercise under similar circumstances.”46

In 2023, the Alaska Board of Pharmacy transitioned to a standard of care model through negotiated administrative rulemaking. The change has already spurred a spring-cleaning of administrative rules, including expanding pharmacist scope of practice and continuation of therapy, and more recently becoming the fourth state to remove the Multistate Pharmacy Jurisprudence Examination (MPJE) as a prerequisite of pharmacist licensure.47 In 2024, the Iowa General Assembly passed and Governor Kim Reynolds signed HF 555 adopting a standard of care regulatory approach for pharmacy practice. Coupled with a zero-based regulation executive order, the Iowa Board of Pharmacy is poised to remove 13 chapters, 141 rules, and 36,000 words from the books.48–49

A New Model For States

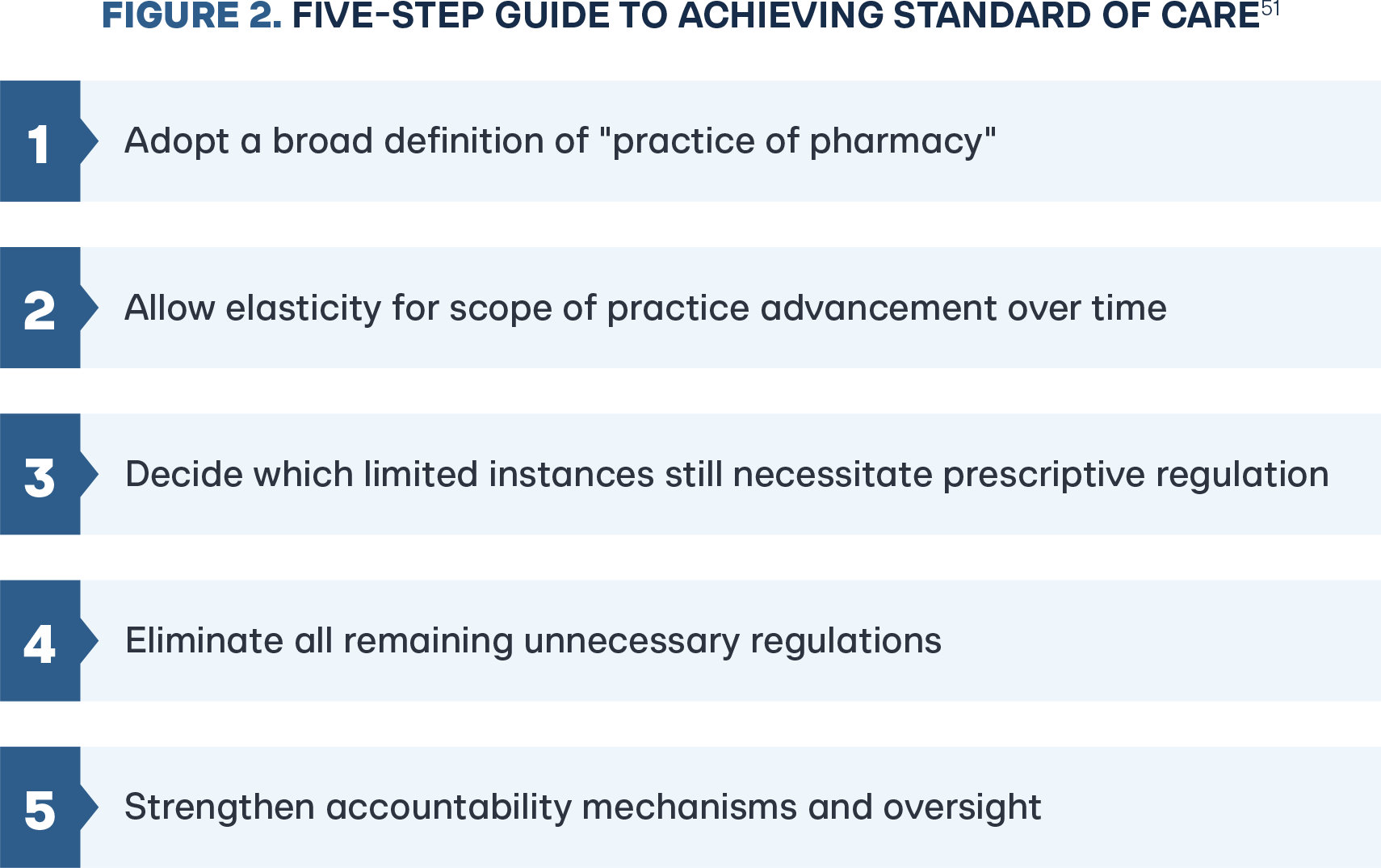

Adams and colleagues delineate a five-step guide for state policymakers and pharmacy advocates to achieve a standard of care regulatory model based on the experience and lessons learned in Idaho (Figure 2).50 Of note, by transitioning to standard of care, both Alaska and Iowa integrated elasticity for pharmacist scope of practice over time, as well as ensconced the appropriate accountability mechanisms (Figure 1). As Iowa progresses toward pharmacist full practice authority, a future update to their standard of care statute should include extending the framework to delegation of services to pharmacy technicians and unlicensed personnel. Step one to freeing pharmacists from decades of regulatory capture is adopting explicit standard of care language.

Defining Full Practice Authority

Adopting a standard of care regulatory model allows the pharmacy profession to rethink how to define traditional norms regarding pharmacist scope of practice. Ross and colleagues eloquently made a call to action for the profession to stop referring to new pharmacy practice services as “expanded, enhanced, or expanded scope of practice,” and outlined a pathway towards full scope that includes performance of prescribing, deprescribing, drug administration, prescription adaptation, laboratory test, and disease management.52–53 At the core of achieving full practice authority is the underpinning of independent authority and evidence-based practice unhindered by outdated legislation and regulatory restrictions.

“Full-scope pharmacist services include all proactive and comprehensive interventions that prevent or manage illness and are within an individual’s competency to perform independently.”

—Dr. Ross Tsyuki

Chair of the Department of Pharmacology, University of Alberta54

Before creating a new defining standard, the pharmacy profession should consider learning from the jurisdictional challenges and historical success of advanced practice registered nurses’ (APRNs) pursuit of full practice authority. The American Nurses Association (ANA) states, that full practice authority is generally defined as an APRN’s ability to utilize knowledge, skills, and judgment to practice to the full extent of his or her education and training. Notably, this definition is inherently standard of care and does not create a specific list of permitted authorities.55 The American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) defines full practice authority as the authorization of nurse practitioners (NPs) to evaluate patients, diagnose, order and interpret diagnostic tests and initiate and manage treatments—including prescribing medications—under the exclusive licensure authority of the state board of nursing.56

In the establishment of independent full practice authority, state boards of nursing: (1) implemented standard of care; (2) agreed on a scope of nursing practice decision-making framework; and (3) adopted broad definitions to the practice of nursing and practice of advanced practice registered nurses.57 In addition, any state with limitations to independent authority functionality or requiring physician oversight through restrictive collaborative practice agreements or supervision ratios are deemed reduced practice or restrictive practice states.58 Rather than reinventing a new regulatory method or implementing a prescriptive bright-line approach as pharmacy, the profession of nursing mirrored the successes of physicians and the broad definition of the practice of medicine to allow new innovation and practice at the top of each clinicians education, training, and experience.

Toward Collaborative Practice, Not Collaborative Practice Agreements

Previous pharmacy research variations in state advancement on scope of practice can be best described on a continuum of innovation, indicating not all changes in state scope of practice laws are good for patient care, and that some advancements are simply poor concessions that should outrightly be opposed.59 In 1979 for example, Washington state became the first state to permit pharmacists to enter population-based collaborative drug therapy agreements to initiate therapy. With decades of peer-reviewed literature and patient safety outcomes supporting the Washington state approach, more than 35 states followed by passing restrictive patient-specific collaborative practice laws.60 More often than not these laws are unusable and impractical in community pharmacy settings. In 2021, Adams and Weaver noted that to fully engage in the Pharmacists’ Patient Care Process, states must allow an aggressive continuum toward pharmacists’ authorization to (1) order and interpret laboratory tests; (2) prescribe medications; (3) adapt medications; (4) administer medications; and (5) effectively delegate tasks to support staff.61

The failed timeline of implementing population-based collaborative practice across the states, medical boards threatening litigation in states where authority has existed for decades, and the lessons learned from APRNs, physician assistants, psychologists, and optometrists on scope advancements indicate that moving forward states should only pursue independent practice models.62 State and national medical associations openly use existing collaborative practice laws as a fulcrum to oppose full practice authority for every healthcare professional.63

Dependence on collaborative practice agreements is dependent on a delegated authority. A legal authority founded on delegation can be undelegated at any time. Rescinding authority pulls the rug out from under from patients and innovation in practice. While collaborative practice agreements may have been the starting point for the past four decades, a new prescription calls for pharmacists to abandon efforts to appease medical opposition with poor concessions that impede patient access to pharmacist services. As such, this research aims to prescribe a continuum of full practice authority for the states, indicating critical regulatory barriers to remove, and pivot toward full practice authority.

Pharmacist Full Practice Authority: Diagnosis and Prescribing

The pathway for states achieving independent authority to diagnose and prescribe has historically been that of one-off legislative authority for a specific drug or disease state category.64 As states have successfully implemented limited independent prescribing categories for common drug categories such as immunizations, smoking cessation, naloxone, epinephrine, tuberculin purified protein derivative, and hormonal contraceptives, among others—states have experimented with broad governance models such as: (1) medical-veto model sharing authority between boards of pharmacy and boards of medicine; (2) interdisciplinary committee of appointed healthcare providers; (3) board of pharmacy formulary list; and (4) standard of care diagnosis and prescribing model.65 The literature detailing uptake, patient outcomes, and experiences from Florida (1985) and New Mexico (1993)—and more recent models implemented in Colorado (2017), Oregon (2017), and Idaho (2017)—indicate that a pharmacist-determined diagnosis and prescribing model based on standard of care is the gold standard for states to pursue.66,67,68,69,70,71

Perhaps this is best demonstrated by states that experimented with a model but within a short timeframe upgraded to standard of care. Montana, California, North Carolina, and New Mexico initially pursued advanced practice pharmacist (APP) designations, but research demonstrates these APP designations have low pharmacist uptake and unnecessary barriers to entry such as limited collaborative practice agreement scope and additional licensure thresholds.72

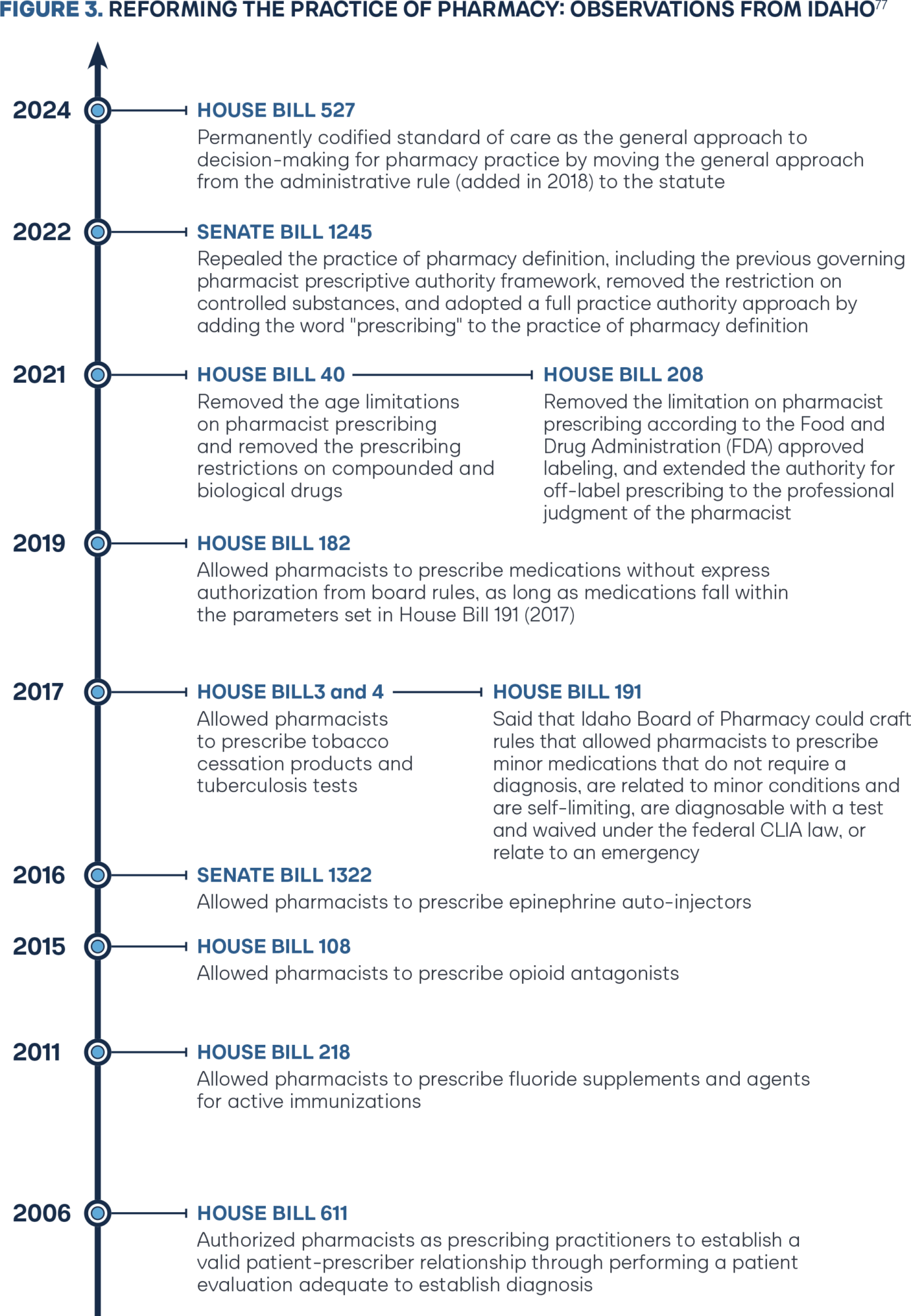

Montana has since abandoned the APP designation of “pharmacist clinician” and California updated the authority for APP pharmacists from collaborative practice authority to independent authority. In 2021 and 2023 respectively, Colorado SB 21-094 and Montana SB 112 upgraded to a pharmacist-determined standard of care for diagnosis and prescribing.73–74 Previous research from Broughel and colleagues well documents the pathway Idaho paved from 2011 until 2019 in implementing a pharmacist-determined diagnosis and prescribing model through numerous legislative and regulatory board efforts (Figure 3).75 In 2024 Tennessee SB 869 followed the Idaho 2017 approach, accomplishing a strong starting framework list of one-off drug categories pharmacists may prescribe under a standard of care framework.76

The momentum in Tennessee accomplishes many of the independent prescribing advancements of California, Oregon, Vermont, Virginia, and Utah without the restrictive mandatory protocol criteria adopted by the Board of Pharmacy through regulations. The starting point for states pursuing independent diagnosis and prescribing should begin with the basis of Idaho, Colorado, and Montana.

The core elements of the original Idaho (2017 & 2019) legislation and companion legislation in Colorado (2021) and Montana (2023) have been enshrined in the following model policy for pharmacist prescribing authority:78

Section 1. Short Title

This Act shall be known and may be cited as the Pharmacist Prescribing Authority Act.

Section 2. Purpose

The purpose of this Act is to authorize pharmacists to practice the full extent of their education and training to prescribe medications to patients.

Section 3. Practice of Pharmacy

Practice of Pharmacy means:

The prescribing of drugs, drug categories, and devices that are limited to conditions that:

(i) Do not require a new diagnosis;

(ii) Are minor and generally self-limiting;

(iii) Have a test that is used to guide diagnosis or clinical decision-making and are waived under the federal Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988; or

(iv) In the professional judgment of the pharmacist, are patient emergencies.

Idaho, Colorado, and Montana were the first states to explicitly permit broad authority for a pharmacist to independently diagnose (1) minor or generally self-limiting (minor ailments); and (2) conditions guided by the results of a laboratory test. A robust body of evidence of patient acceptance, patient demand, and patient safety profile for minor ailments and chronic diseases in Canada, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Australia supported these actions.79 States have a longer history of pharmacists performing diagnoses based on the results of laboratory tests for influenza and group B streptococcus, as well as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) pre-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and HIV postexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), being the most common.80

In July 2022, pharmacist independent authority to diagnose patients based on laboratory testing was catapulted on the national scale when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) revised its emergency use authorization for Paxlovid, allowing pharmacists in all states to prescribe the drug for patients who test positive for COVID-19.81 While the FDA approach was over-regulated and inconsistent with the standard of care permissions they created for other health professionals, the change spurred action across multiple states to introduce legislation to make the allowance permanent. Tennessee SB 869 (2024) is a recent example, now permitting a pharmacist to independently prescribe antivirals for influenza and COVID-19 that are waived under the federal clinical laboratory improvement amendments of 1988.82

With Zalupski and colleagues recently reporting that 51 percent (29,011) of U.S. pharmacies hold a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) waiver, authorizing the performance of diagnostic laboratory testing—pharmacist diagnosis in primary care settings is gaining momentum.83 Many state pharmacy scope of practice restrictions preempted in 2020 during COVID-19 by the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) declaration under the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act (PREP Act) are set to expire at the end of 2024, creating urgency for permanent patient access solutions.84

“If waiving these regulations was deemed necessary to improve public health and welfare during the declared emergency, there is a rebuttable presumption that the regulations are unnecessary or counterproductive outside of the declared emergency.”

—Idaho Governor, Brad Little85

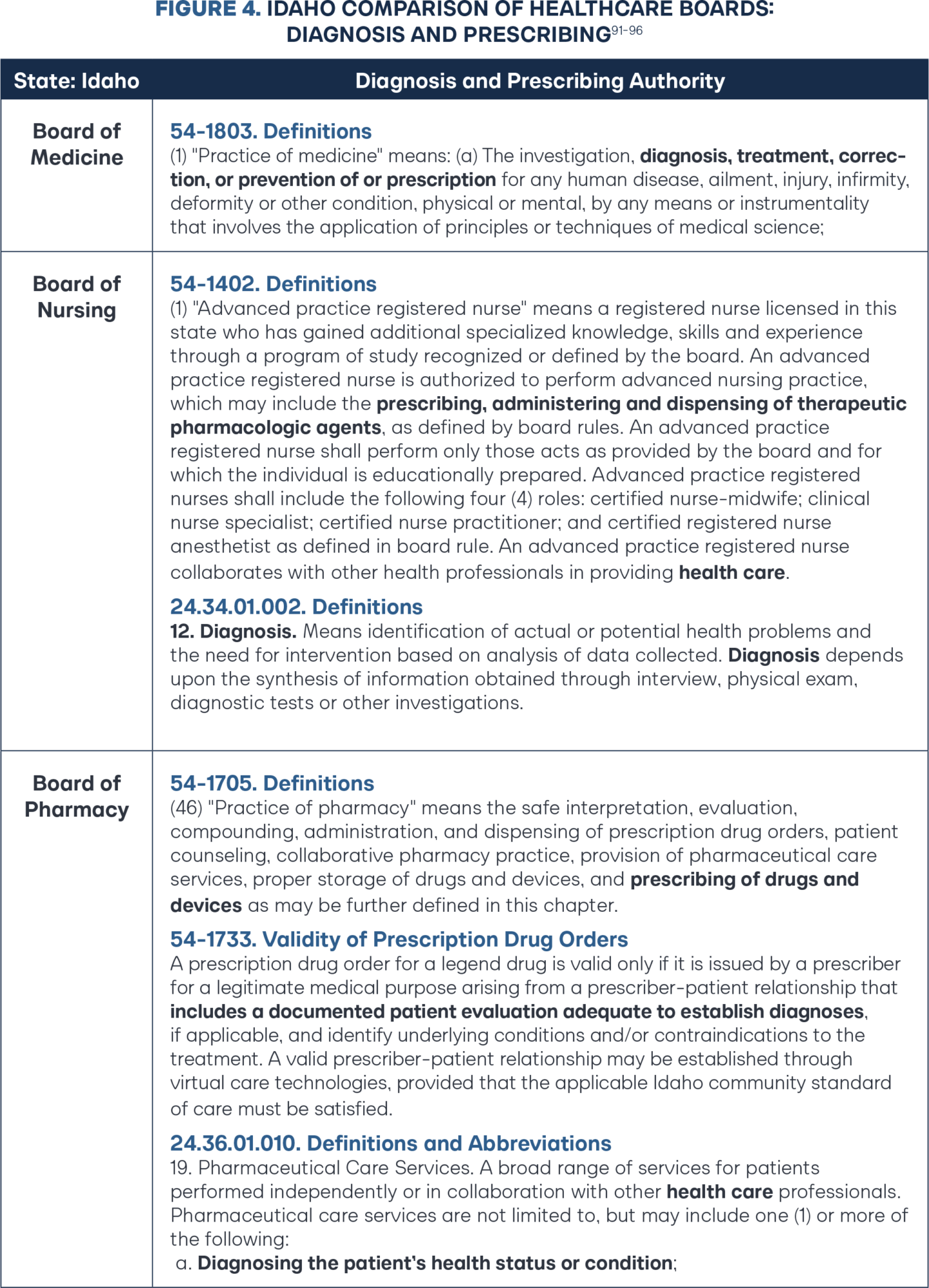

Since the initial HB 191 (2017) diagnostic and prescribing authority framework, the Idaho Legislature has taken multiple definitive steps to move Idaho pharmacy law to better reflect the independent authority found within the practice of medicine and the practice of advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs). In 2021, Idaho HB 40 removed all remaining age limitations and removed the prescribing restrictions on compounded and biological drugs.86 In the same year, Idaho HB 208 removed the restriction of only prescribing according to federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labeling, again extending the professional judgment to pharmacists.87 In 2022, Idaho SB 1245 repealed the practice of pharmacy definition, including the previous governing prescriptive authority framework, and replaced the definition with one word: prescribing (Figure 4).88 In 2024, Idaho HB 527 spurred updates to the definition of pharmaceutical care services to more explicitly authorize independent diagnosis, amending language from “performing or obtaining necessary assessments of the patient’s health status” to new language stating, “diagnosing the patient’s health status or condition.”89 The changes dovetail nicely with governing statute authority that has been in place since 2006 that includes pharmacists as a “prescriber” and requires a valid prescription to include “a documented patient evaluation adequate to establish diagnoses.”90

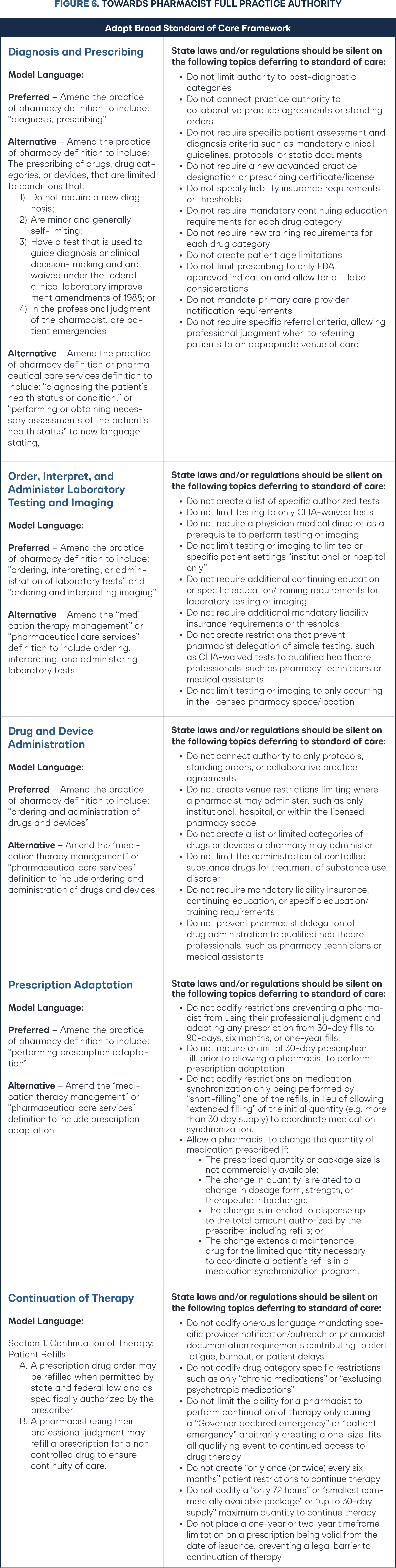

Bridging Clinical Services Gap: Full Practice Authority and Standard of Care

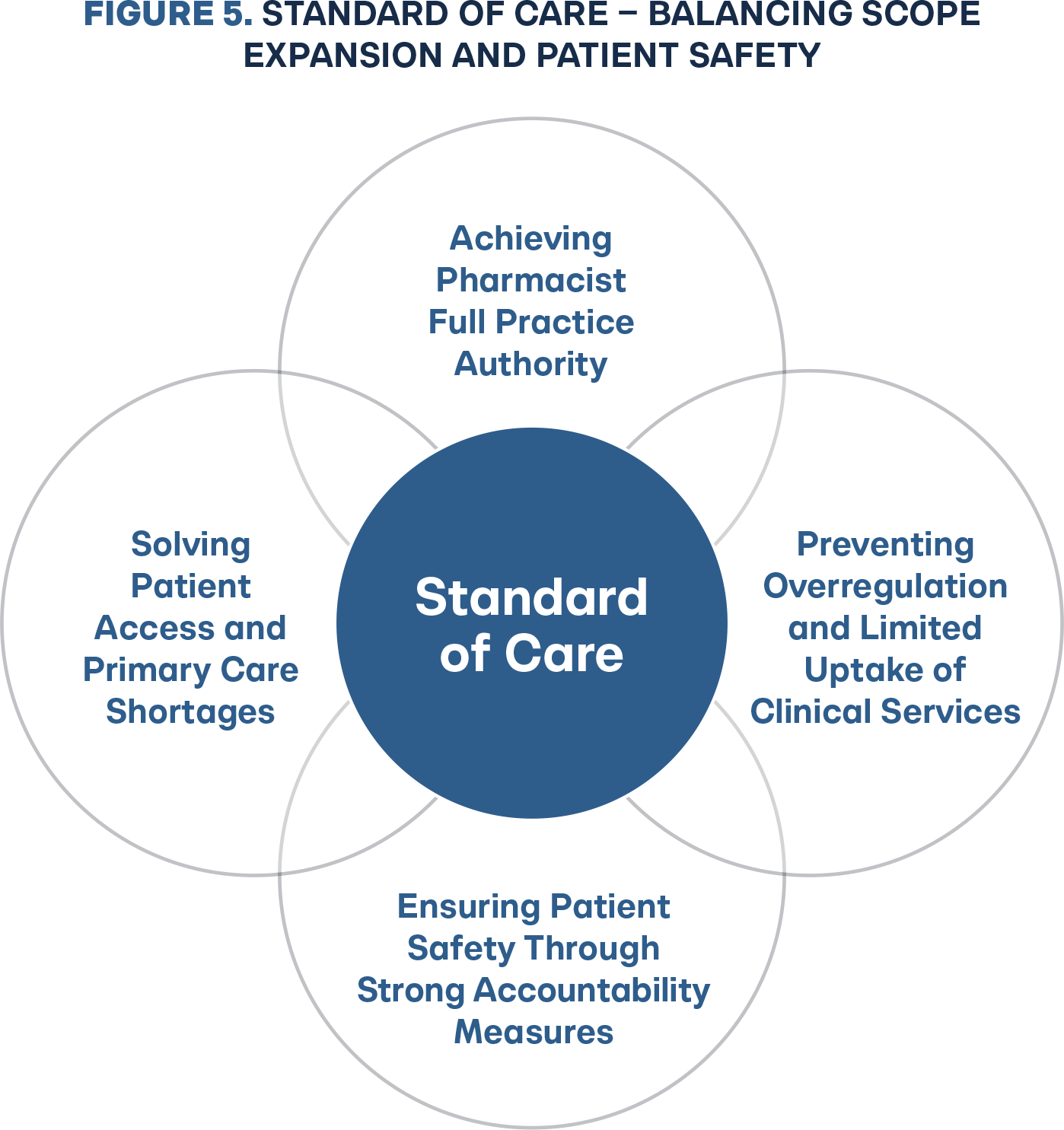

Implementing full practice authority under a standard of care regulatory framework means rejecting the state experimentation with three to 15 page mandatory protocols for each independent prescribing drug category. These protocols and patient algorithms are static in time and not clinically dynamic with changes in guidelines, requiring state rulemaking for updates. Before standard of care, it stands to reason state Boards of Pharmacy would consider building all the patient inclusion and clinical guidelines into the rule. Adopting a standard of care framework equips the legislature and Board of Pharmacy with the necessary accountability tools to create a balance between patient access and patient safety (Figure 5). Legislators and pharmacy stakeholders who have accomplished independent prescribing through one-off drug category protocols and broad governance models should celebrate the foundational success, but embrace the change to the pharmacist-determined diagnosis and prescribing model based on standard of care (Figure 6). There is a wide margin of error from legislative bill introduction to a governor’s signature to the final board rule that determines whether a new practice authority will be operationally usable by business, let alone optimal. States should generally solely rely on the statute authority framework and reject all board rulemaking, deferring to standard of care.

Conclusion

Pharmacist full practice authority is a proven safe and evidence-based solution to solving the primary care shortage crisis. Pharmacists are highly trusted, doctorate-trained healthcare providers able to diagnose and manage chronic diseases and minor ailments, decrease unnecessary emergency room visits, and deliver preventative health outcomes.

Governors should direct executive agency Boards of Pharmacy to prioritize regulatory rewrites to unravel the overregulation of pharmacy clinical services and transition to a standard of care model, maintaining strong back-end accountability mechanisms while championing business innovation and patient choice.

Legislators and policymakers should update their state “practice of pharmacy” definitions, following the success of Idaho, Colorado, and Montana, rejecting the anecdotal physician protectionism masquerading as patient safety concerns and embracing independent pharmacist diagnosis and prescribing based on the community standard of care. Legislative and regulatory strings prevent pharmacists from practicing at the top of their education, training, and experience. It is long past due for the pharmacy profession to move to a standard of care regulatory model and for states to pursue pharmacist full practice authority.