Unwinding Delegation:

Taking Back Power from the Administrative State

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Adam Jones, Boise State University, for his contributions toward statistical analysis and regulation calculations.

Issue Areas

Related Content

Background

The future of innovation in the United States is at stake due to state and federal regulations that hinder economic growth and impede human flourishing. Although the Constitution assigns the legislative branch the responsibility of creating laws, this branch has increasingly delegated the task of crafting detailed and clear legislation to executive branch agencies. The rise in federal and state regulation is directly related to this broad delegation of authority. It has led to a proliferation of regulations, many of which were likely never intended by the legislatures that crafted the initial legislation.

Legislatures often pass bills expressing only a general policy concept, leaving executive branch agencies to adopt regulations that fill in many of the implementation details. Executive branch regulations have the force and effect of law and can trigger fines, business revocations, and other penalties for non-compliance. Businesses must navigate an incoherent web of 50 different state codes in addition to federal rules, creating a patchwork of compliance challenges that can cripple even the most resilient enterprises.

Critics of such delegation suggest that executive agencies may abuse ambiguity in the law or the broad authority granted decades previously to create new policies, often with limited political accountability. Many process reforms have been suggested to address this problem. These include legislative review and approval of regulations, curbing broad delegations of authority to agencies, cost-benefit analysis, and using sunset provisions to require periodic review of regulations, among other proposals. However, one of the simplest but boldest solutions is moving existing regulations into statute using a targeted process to cut existing regulatory strings while also un-delegating the associated rulemaking authority. A turning point for regulation is thus to reverse course–return the power to regulate to the legislature, a branch that is fully electorally accountable to the people.

One of the arguments proponents use in favor of executive rulemaking is that legislators must deal with a wide range of issues and, therefore, adopt the role of generalists. Executive agencies, by contrast, can hire specialists who sort through technically complex matters and have the time to review and respond to hundreds of comments submitted by interested parties as required under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). The rulemaking process can take years of work from the executive agency staff. Once they have completed this work and rules are adopted, it stands to reason that regulations may be comfortably moved to statute at a certain time.

Yet, several arguments may credibly speak to not moving existing regulations to statute. For one, regulations, like any law, may have unintended consequences, and agencies may be able to update regulations more nimbly than a legislative body. Giving some agencies the flexibility to change rules and adapt may prove essential, especially in states with part-time legislatures. Regulations, therefore, may be ideal in situations in which flexibility is needed, frequent changes are anticipated, or emergencies may arise that necessitate quick responses. Arguments for and against unwinding delegation of rulemaking to the executive branch are perhaps best described as “regulatory trade-offs.” Speed and simplicity in the rulemaking procedural process can be a double-edged sword, wielded through changes across gubernatorial administrations and changes to agency leadership.

Unwinding Delegation: Idaho Case Study

By exploring the regulatory trade-offs and administrative levers of unwinding delegation, this paper leverages publicly available data from Idaho, a state with a part-time legislature, to determine: 1) the average age of regulations; 2) the frequency of changes to regulations; and 3) how often agencies have invoked temporary rulemaking and waiver authority. Collectively, these items will shed light on the feasibility of moving regulations to statute relative to the potential concerns previously mentioned. Lastly, this manuscript will review the experience of recent Idaho bills that moved regulations to statute from the 2022 through 2024 legislative sessions, including the impact on net regulatory burden.

Average Age of Regulations

To calculate the average age of regulations in Idaho, a random sample of 10 percent of rule chapters was pulled from the 2018 administrative code and again from the 2020 administrative code.1–2 Rule chapters are a grouping of related agency rules by topic area and consist of many rule subparts. For example, a chapter of rules exists for the State Board of Accountancy entitled Idaho Accountancy Rules. It contains nearly 30 individual rules, referred to here as rule subparts, that all relate to accountant licensure. For example, one rule subpart notes that a “candidate who fails to appear for the CPA Examination forfeits all fees paid.”

The years 2018 and 2020 were selected for this study as they were the most recent years Idaho had complete history notes showing the year that the agency last updated each rule subpart. If a rule subpart had multiple components, the most recently updated year was used and applied it to the whole subpart. The age of each rule subpart was observed and calculated as the study year (2018 or 2020) minus the year the rule subpart was last updated. The average age of the overall chapter was calculated by summing the age of each of the chapter’s rule subparts and then dividing by the number of rule subparts.

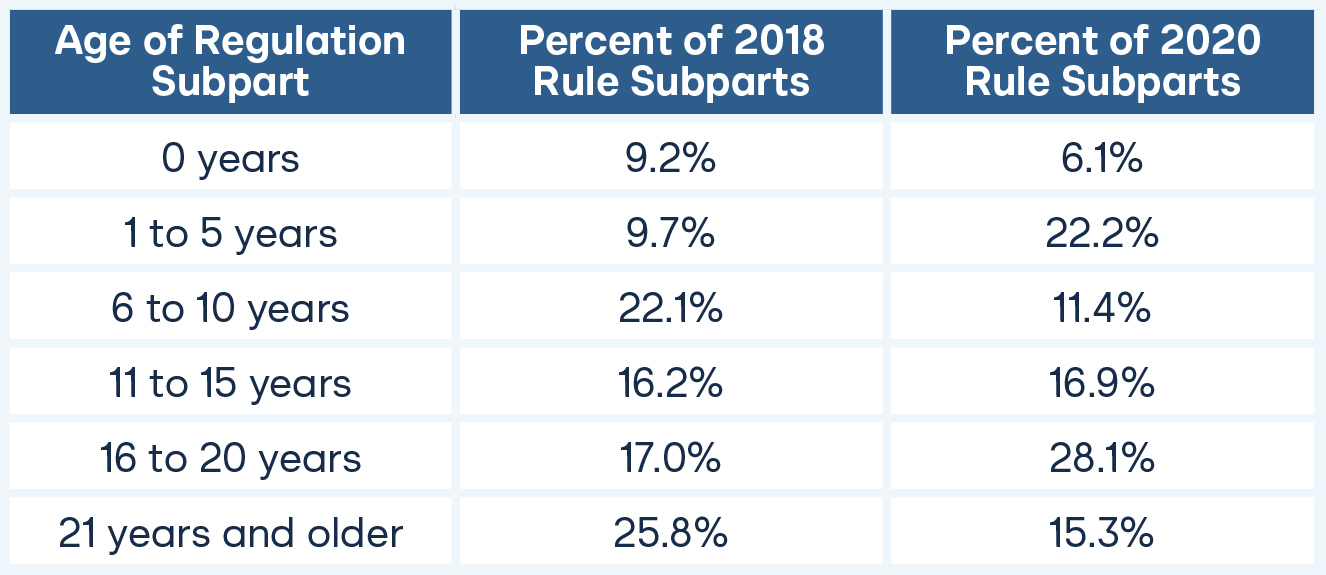

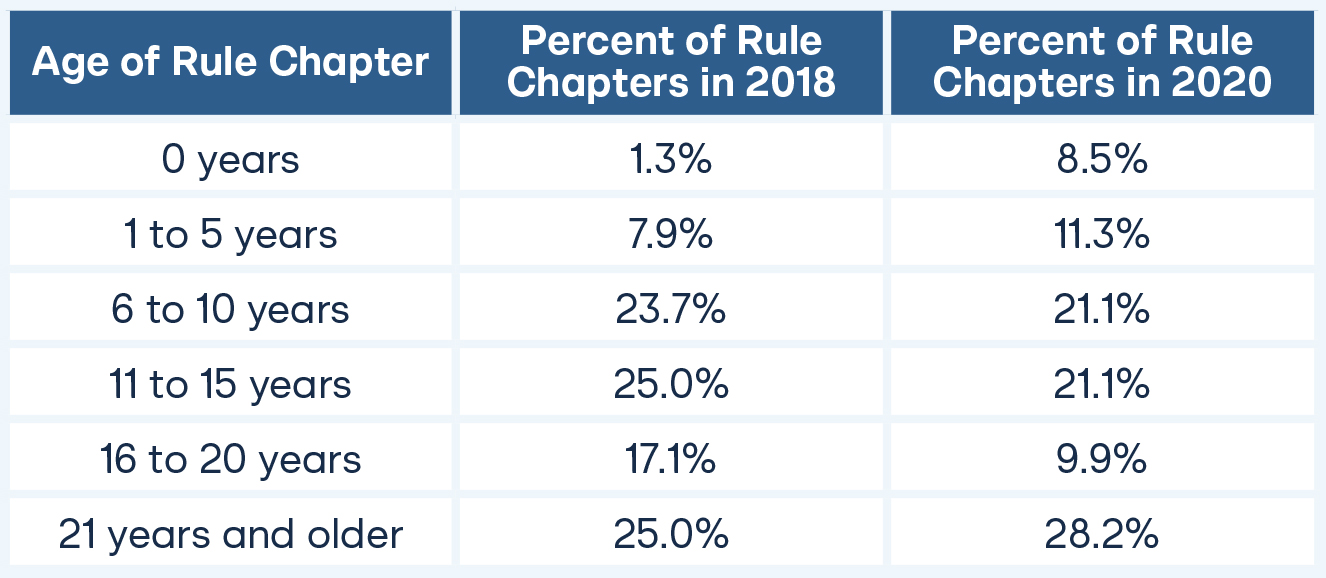

In 2018, a total of 1,762 rule subparts from 79 rule chapters at 29 agencies were included in the random sample. The average rule subpart was last updated 14 years ago. More than 80 percent of rule subparts were last updated six or more years ago (Table 1). Similarly, more than 90 percent of rule chapters had an average age of six or more years (Table 2).

The random sample methodology was repeated for 2020 because Idaho undertook a major statewide regulatory reform effort in 2019 that eliminated many rule chapters and rule subparts that agencies judged to be outdated, obsolete, or otherwise unnecessary. The state eliminated a reported 1,800 pages of regulations. It is reasonable to assume this could lower the average age of regulations, as the oldest, likely obsolete, regulations were probably eliminated.

In 2020, the random sample included a total of 1,632 rule subparts from 71 rule chapters at 20 agencies. The average rule subpart was last updated 13 years ago (range 0 to 59 years), just one year newer than the 2018 random sample despite the major regulatory reform effort in the intervening period. In addition, more than 70 percent of the rules were also updated six or more years ago as were more than 80 percent of rule chapters.

Table 1. Average Age of Regulation Subparts in 2018 and 2020

Table 2. Average Age of Rule Chapters in 2018 and 2020

Frequency of Rule Chapter Edits and Waivers

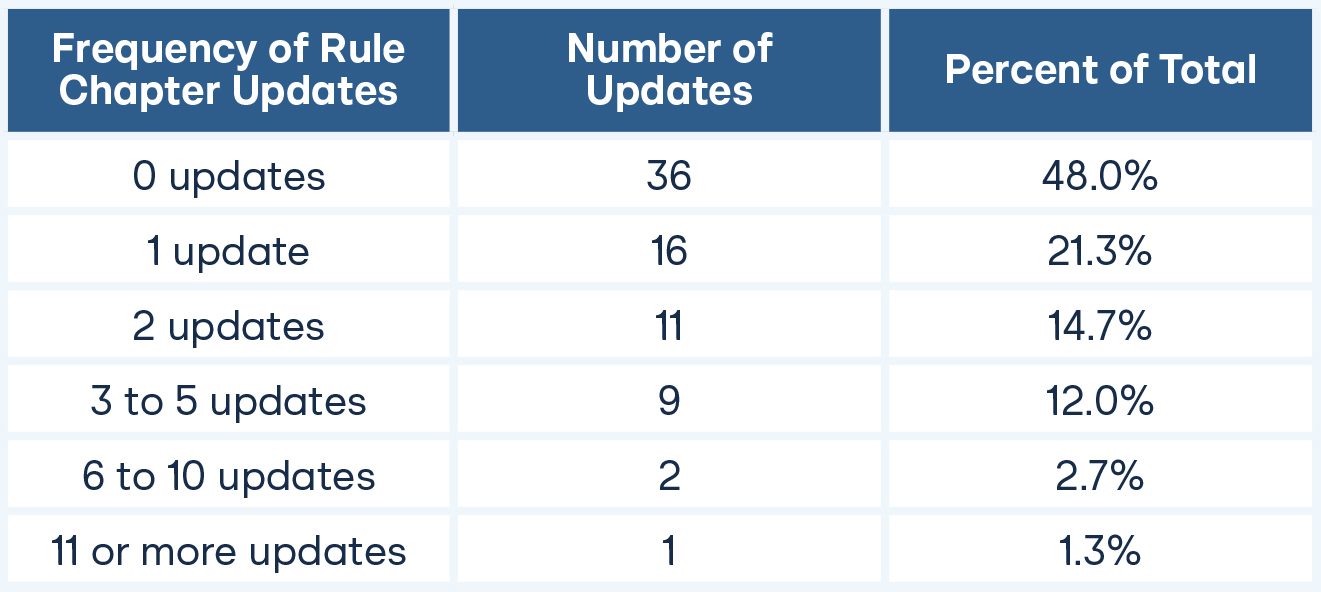

To calculate the frequency of edits to rule chapters in Idaho, a new random sample of 10 percent of rule chapters was pulled from the 2018 administrative code. The cumulative rulemaking index was then utilized for each agency to calculate the number of pending rules that were adopted for each rule chapter from 2010 through 2018. This timeframe was selected because in 2019 and each year thereafter, the frequency of rulemaking was arbitrarily increased due to sunset dates established as part of a statewide regulatory reform effort. Therefore, the nine-year study period was judged to provide the most organic frequency rate for rule chapter edits.

A total of 75 rule chapters at 27 agencies were included in the random sample. Agencies adopted an average of 1.4 total pending rule changes per chapter (range from 0 to 13) in the nine-year study period. Put another way, agencies updated their rules, on average, just once in nine years. The largest number of changes were to the motor fuels tax administrative rules. Nearly half (48 percent) of all rule chapters had zero updates in the nine-year period, and more than 80 percent had two updates or fewer (Table 3).

Table 3. Frequency of Rule Chapter Edits from 2010–2018

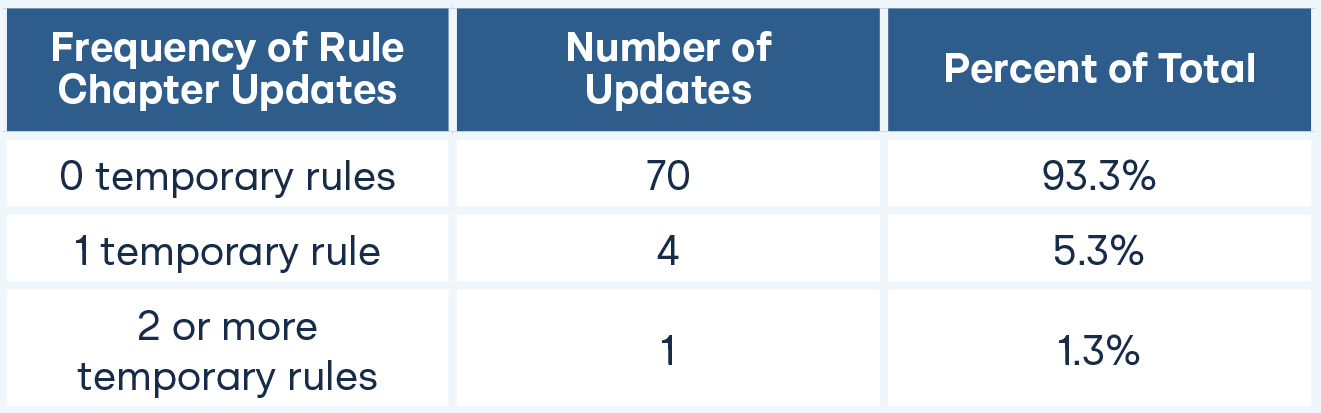

The same sample of rule chapters was used to calculate the frequency of edits and determine the frequency of temporary rulemaking. The Idaho Administrative Procedure Act (APA) allows limited temporary rulemaking if the Governor finds that a rule must take effect quickly to protect public health, safety, or welfare; to comply with a deadline; or to remove a regulatory burden that would otherwise impact individuals or businesses.3 Because temporary rules circumvent the traditional legislative review process, the volume of temporary rulemaking may serve as a proxy for the flexibility agencies need to make quick changes to regulations.

The data shows that temporary rule updates were rare. In the nine-year period covered in the study, agencies adopted an average of just 0.1 total temporary rule changes (range from 0 to 4). Most agencies (93.3 percent) did not adopt a temporary rule in nine years (Table 4).

Table 4. Frequency of Temporary Rule

- During the 2020 Legislative session, Idaho amended the APA to allow individuals to petition for a waiver of a regulation if it met one of three scenarios:

- The rule is unreasonable and would impose undue hardship or burden on the petitioner.

The petitioner proposes an alternative that will afford substantially equal protection of health, safety, and welfare intended by the rule. - The waiver will test an innovative practice or model that will generate meaningful evidence for the agency in consideration of a rule change.4

Waivers, like temporary rules, may serve as a proxy for needed regulatory flexibility. Across all agencies, just 13 rule waivers were requested, and seven were granted in the nearly four-year period. Most (86 percent) of the granted waivers were concentrated in one agency (Division of Occupational and Professional Licenses).5

Rule Chapters Moved to Statute

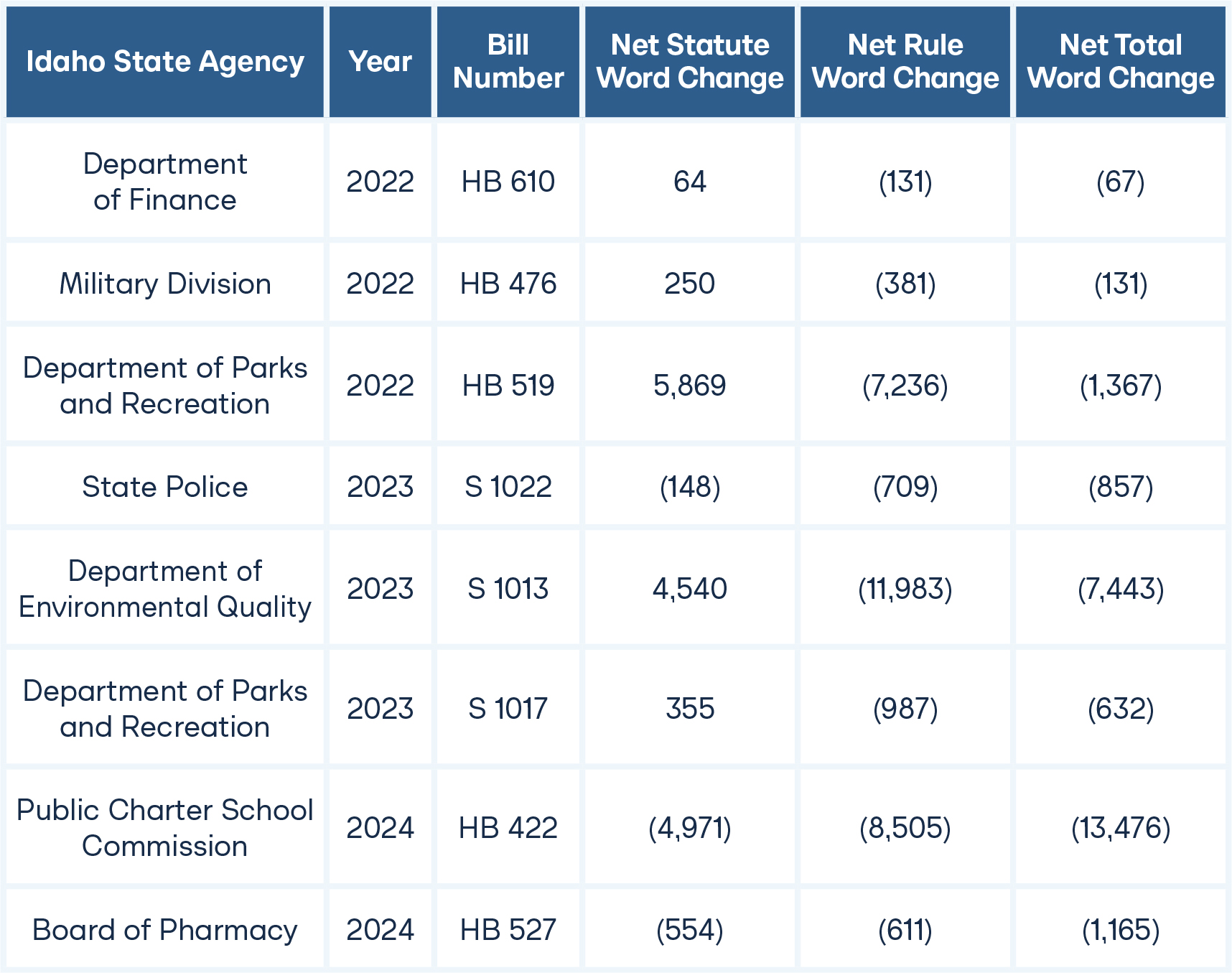

Since 2022, eight bills from seven executive branch agencies were introduced that sought to move existing regulations to statute. All eight passed overwhelmingly, with a collective vote tally of 915 ayes, six nays, and 24 absent or excused, reflecting a 96.8 percent approval rate. Collectively moving these eight chapters to statute added 5,405 words to statute and eliminated 30,543 words from regulation, for a net reduction of 25,138 words (Table 5). Assuming 500 words to a page, these actions eliminated more than 50 total pages of regulation.6

Table 5. Rule Chapters Moved to Statute from 2022–2024

Necessary Agency Flexibility or Venue for Regulatory Capture?

After agencies adopt regulations and they remain in place over time, two of the most credible arguments against moving them to statute are the need for agency flexibility with the regulation moving forward and the need for frequent regulatory changes. Consider the opposite hypothesis, what if “agency flexibility” is simply a catchy phrase to shift the balance of regulatory capture towards a more favorable venue outside the legislative process? Data in Idaho generally debunks the argument that “agency flexibility” is needed as regulations changed infrequently, and authority granted to agencies for flexibility (e.g., waivers and temporary rulemaking) was rarely invoked. Idaho rule subparts had an average age of 12 to 13 years, and most (>80 percent) rule chapters had an average age of six or more years. As such, the longer the average lifespan of a regulation, the less necessary it is to delegate rulemaking authority to executive agencies.

Unwinding Delegation with Part-time Legislature

To what extent is Idaho representative of other state administrative codes? Idaho has a part-time legislature that meets for 75 to 90 days annually. Thus, it is reasonable to expect that Idaho regulations would change frequently as there is only a short window for statutory changes each year. This did not prove to be the case. Nearly half of all rule chapters had zero updates in the nine-year period, and most agencies (>90 percent) did not adopt a temporary rule in this same time period. Idaho does, however, require legislative review of regulations, which may serve as a deterrent to frequent changes that could skew them to be older and less updated than those in other states. Yet, Baugus and colleagues report that 43 other states have some form of legislative review of regulations, so this potential deterrent effect alone is unlikely to drive significant differences in Idaho’s administrative code relative to other states.7

From the data collected on the eight bills that moved rule to statute in Idaho, it is easy to deduce that many regulations are not controversial. Such regulations had remained on the books for years, even with a petition process where interested stakeholders can press for reconsideration of any rule. Further, when moved to statute, such regulations demonstrated a high approval rate (97 percent) from legislators, with most of the eight bills passing unanimously. What, then, are the potential benefits of moving regulations to statute?

Benefits of Unwinding Delegation

1. Stable Regulatory Environment

Moving regulations to statute may enhance the stability of the regulatory environment and create more certainty for the community being regulated. While Idaho’s regulations were generally updated infrequently throughout the study period, statutes are arguably more stable and durable than regulations. Statutes are less susceptible to changes across gubernatorial administrations and changes to agency leadership. More granularly, changes in legal counsel and regulatory board members can catapult new interpretations of historically stable delegation authority, generating new regulatory burdens never intended by the legislature. Further, when statutes are changed, they are updated by elected officials within the traditional legislative process, which generally means multiple opportunities for stakeholders to engage across legislative chambers, legislative committees, and upon presentment to the governor for final action. Thus, moving completed regulations to statutes can ward off sporadic agency action and ensure updates are done through the legislative process.

2. Reduce Overall Regulatory Volume

Moving regulations into statute can create efficiencies that reduce overall regulatory volume. For example, it is not uncommon to find duplicative definitions in both statute and rule, and regulated entities often must do side-by-side comparisons to see if there are minor definition changes that may impact their approach to business. Clear volume inefficiencies were found in the eight examples of rules moving to statute in Idaho. In fact, only a fraction of the word count was added to statute (5.4k words out of 30.5k words in rule), meaning 82 percent of total rule word count was eliminated during the migration. Lower overall word count can improve readability and make it easier for the regulated community to sort through. Lower word count also reduces legal costs to businesses and other regulated entities for help navigating the legal landscape.

3. Catalyst for Broader Policy Reform

Migration of rules to statute can be a catalyst for broader policy reform. Three of the eight referenced Idaho bills resulted in a net cut to statute even when rules were grafted into code, suggesting other changes were made during the process. One example comes from The Idaho Public Charter School Commission. Only a subset of charter school regulations were deemed necessary and moved to statute. Simultaneously, the commission used the opportunity to address other policy matters in the bill, such as lengthening the duration of licensure for high-performing schools from five to 12 years, allowing fast-track re-application of schools that met the terms of their performance certificate, and allowing charter school operators with multiple schools to serve as a singular local education agency so they may more effectively leverage resources across schools.8 These changes lightened the regulatory burden for charter schools in Idaho while also lowering the overall regulatory volume, promising “innovation and school choice,” as one news outlet put it.9

In 2023, Idaho streamlined telehealth regulations by consolidating telehealth rules from separate healthcare boards into one consolidated statute that governs all licensed healthcare professionals providing virtual care. The legislature used this opportunity to remove the technology modalities to establish a patient-provider relationship, create a consistent standard of care accountability across professions, and create broad licensure exemptions for out-of-state providers servicing Idaho patients in emergencies and continuation of care scenarios, among other things.10 In doing so, the legislature un-wound the previous rulemaking authority of governing licensing boards over virtual care to prevent relapse or new regulatory burdens additions as innovative models are introduced to the market.

4. Lower Cost of Government from Publishing Rules

Moving rules to statutes may lower the cost of government by reducing inter-agency billing for publishing rules. Some states, like Idaho, charge agencies for the publication of administrative rules. For example, Idaho charges agencies up to $61 per page for new regulations or amendments to regulations published in the administrative bulletin to cover the costs of publication and for the newspaper ads required under the Idaho APA to notify the regulated community of potential changes. Further, Idaho charges up to $56 per page annually for each page of regulations republished in the Idaho Administrative Code. Idaho billed agencies $324,800 in 2023 alone for the annual publication of Idaho administrative code. No such charges are assessed to Idaho agencies for corresponding statutes or statutory changes.

Policy Considerations

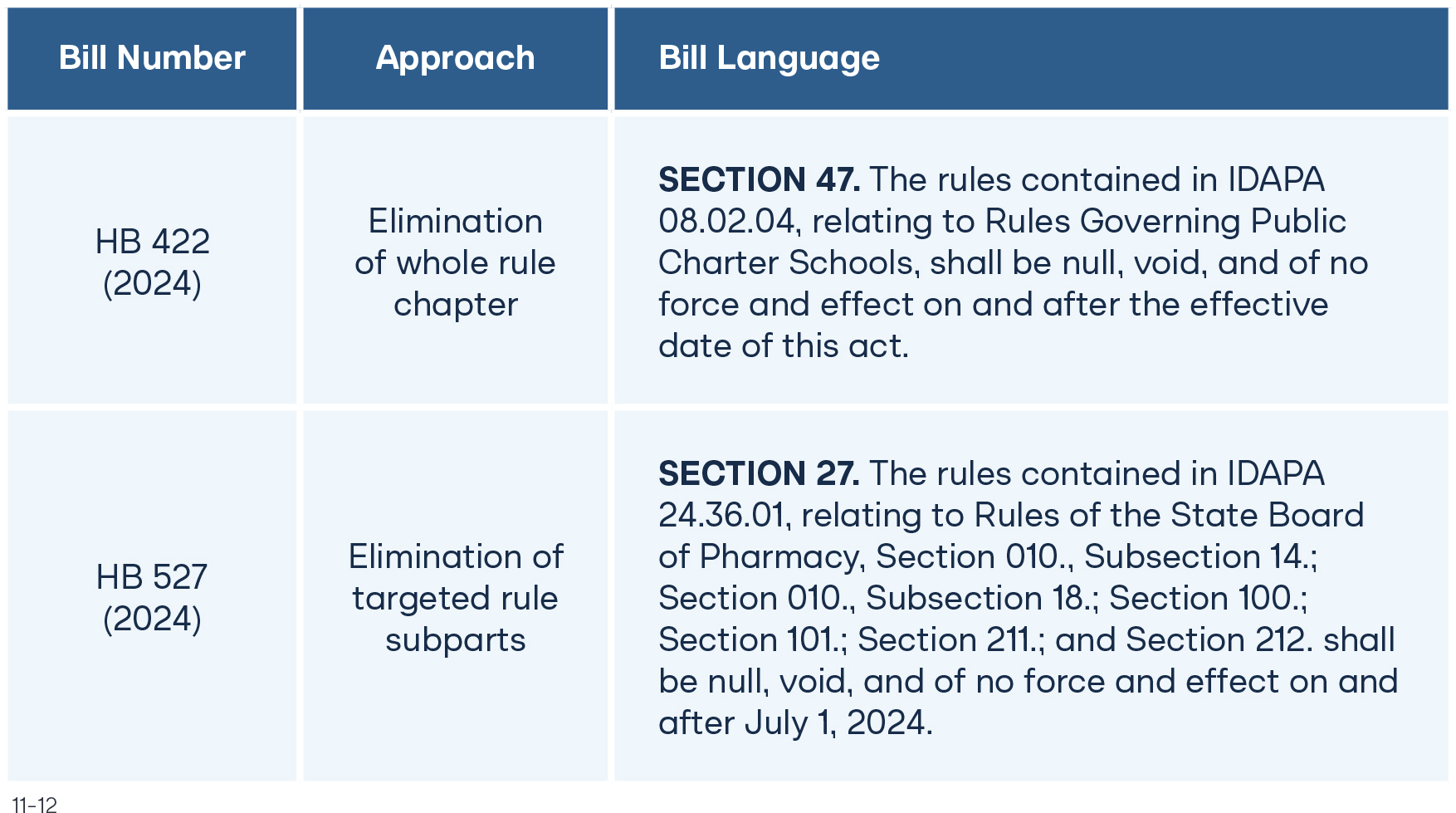

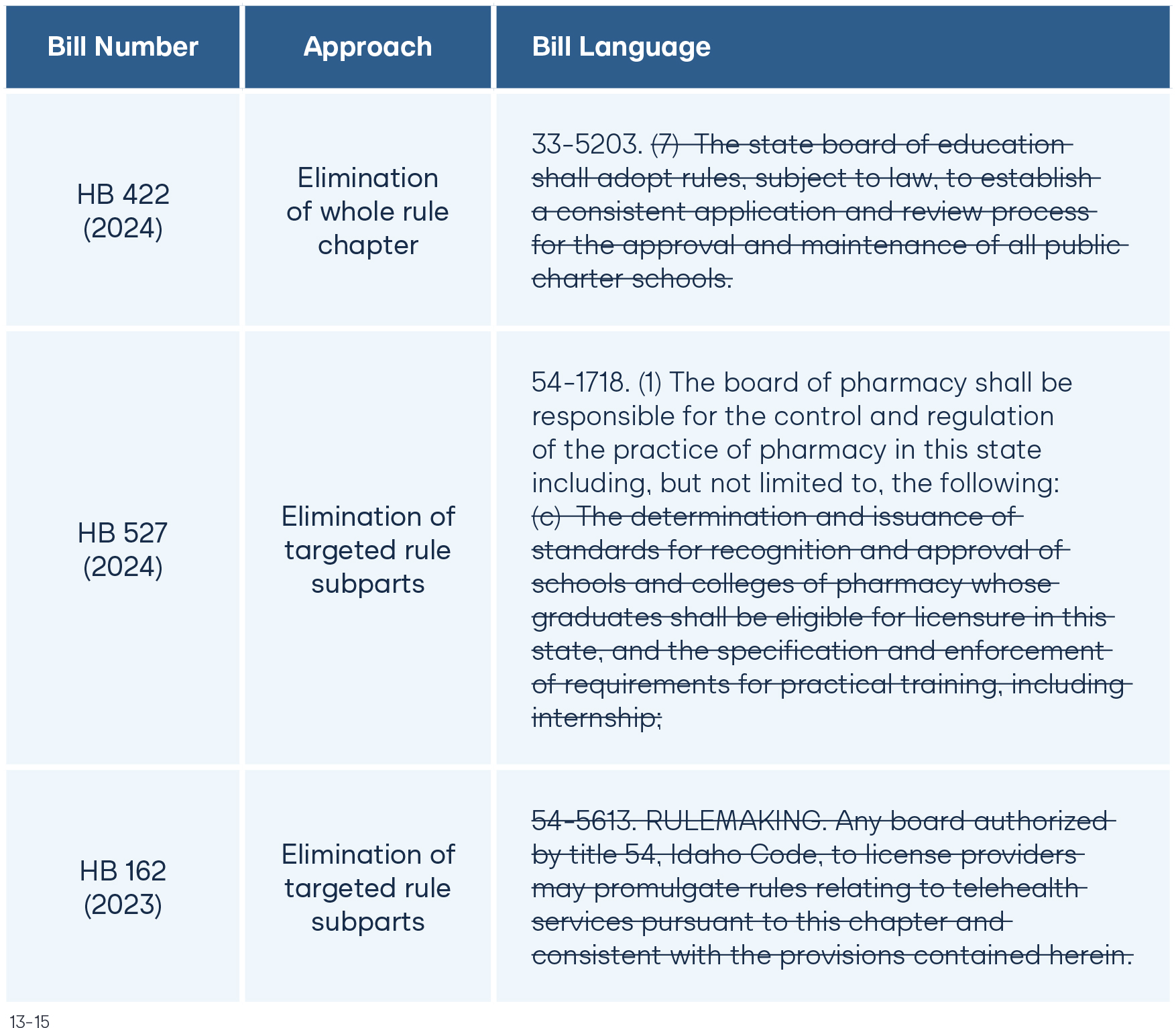

Given these aforementioned benefits, there are several policy considerations to examine. Moving statutes to regulations can be either organic and agency-led, or it can be part of a broader state regulatory strategy formally directed by the legislature. Idaho’s efforts started organically and evolved to the latter. Initially, agencies worked with legislators to move the necessary statutes to rules, and once the legislation passed, a separate rulemaking action was taken to eliminate the corresponding regulation. With more experience, this process was refined and both bills carried in the 2024 legislative session eliminated the agency regulations simultaneously with the statutory changes. Legislation can either eliminate a whole rule chapter or targeted rule subparts (Table 6).

Table 6. Legislative Approach to Elimination

Eliminate Both Regulations and Delegation Authority through Legislation

Both 2024 bills unwound delegations of rulemaking authority (Table 7) either in whole or in part. For example, the bill on charter schools confers no rulemaking authority to the Idaho Public Charter School Commission but does eliminate the rulemaking authority for State Board of Education related to charter school applications. Therefore, any changes to Idaho’s charter school laws moving forward must be done by statute, therefore ensuring that executive agencies will not re-bureaucratize charter schools moving forward.

The pharmacy legislation, however, removed just a targeted rulemaking grant of authority to the Board of Pharmacy. Specifically, the bill removed the board’s authority to determine standards of colleges of pharmacy as well as requirements for internships, and these are now specified in statute. As such, changes moving forward will be at the behest of the elected legislature. To the extent that national accreditation standards for colleges of pharmacy change, these are unlikely to be speedy efforts that necessitate temporary rulemaking. Therefore, they can be comfortably managed in statute, even in a part-time legislature, with appropriate agency foresight.

Table 7. Legislative Approach to Unwinding

Implement Mandatory Sunset or Mandatory Sunset Report

To further formalize the migration of rules to statute, the Idaho legislature passed House Bill 563, which has since been enacted into law. As part of the rolling eight-year review process that the legislature conducts on each regulation, it added that agencies must now report to the legislature “whether the substantive content in the rule chapter is still necessary.” If the agency determines the rule is still necessary, the agency must “report whether the [rule] would be more appropriately integrated into Idaho Code as opposed to remaining as a separate administrative rule.” Notably, the legislature put forth three considerations for agencies in making this determination:

This affirms that the legislature acknowledges some rules are indeed necessary, but it does then make agencies determine if the necessary rules should remain as agency rules or if they should be moved to statute. Thus, this legislation will systematize the efforts for more Idaho agencies to move rules to statute by incorporating it as part of the review process. If Idaho’s early experience proves to be the case, this will continue to reduce overall regulatory volume while having other benefits for the regulated community.

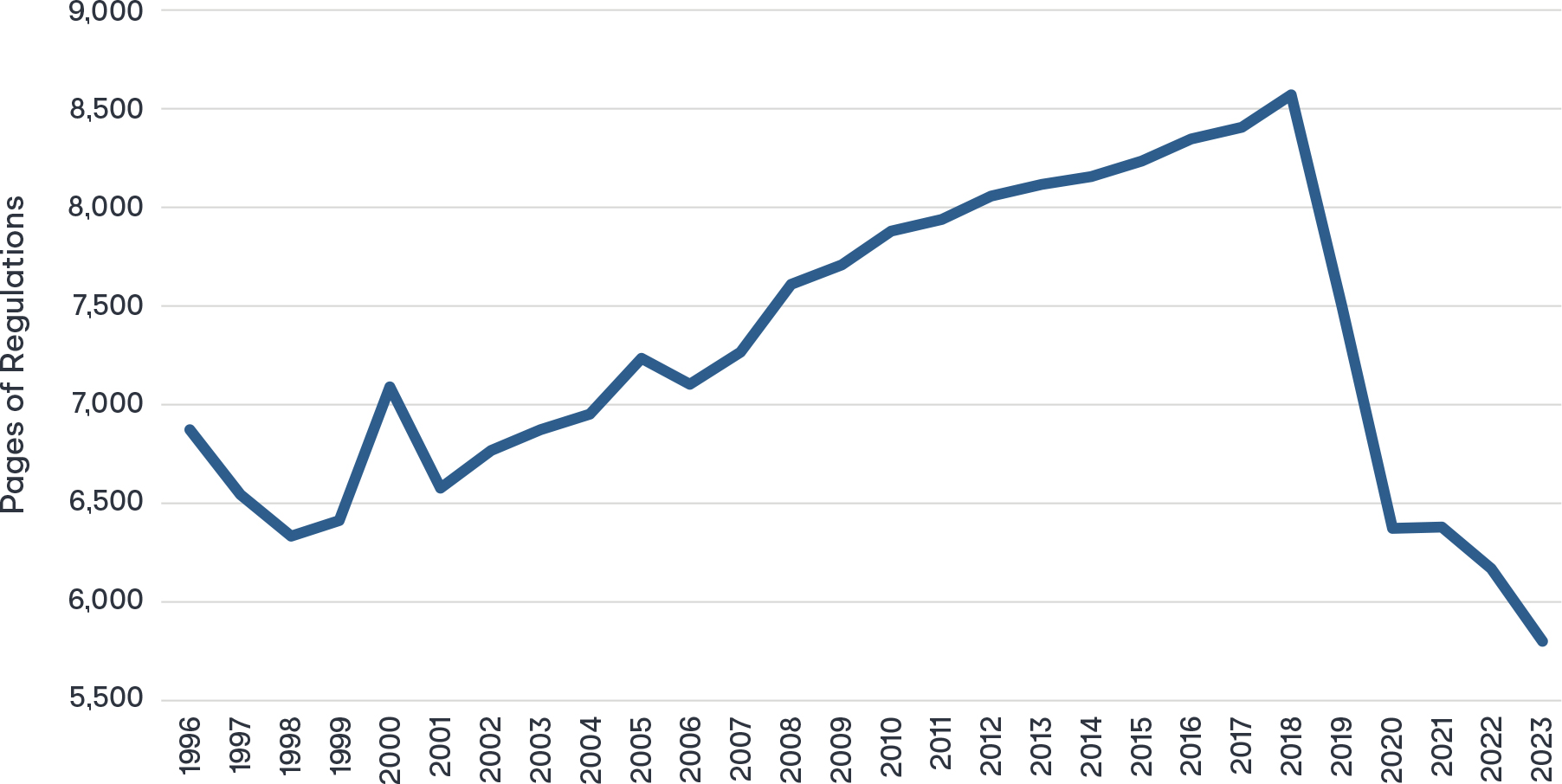

Zero-Based Regulation: An Executive-Branch-Led Mandatory Sunset

While state legislatures continue to rebalance the executive branch administrative code through mandatory sunset, let’s not forget an important tool in regulatory reform–executive-branch-led sunset and red-tape reduction efforts through gubernatorial executive orders (Figure 1).16 In January 2020, Idaho issued Executive Order 2020-10: Zero-Based Regulation (ZBR) requiring a five-year scheduled sunset for each agency rule chapter to be repealed.17 To promulgate a rule, the agency was required to perform a prospective analysis of the rule chapter to determine whether the benefits the rule intended to achieve are being realized, whether those benefits justify the costs of the rule, and whether there are less restrictive alternatives to accomplish the benefits. The agency analysis was guided by the legislative intent articulated in the statute or act giving the agency the authority to promulgate the rule. This analysis of Idaho’s administrative code average age provides insight into states considering an optimum timeframe of mandatory sunset and suggests a five to eight-year timeframe is likely to be reasonable and optimal. Idaho rule subparts had an average age of 12 to 13 years, and most (>80 percent) rule chapters had an average age of six or more years.

Optimistic deregulators will doubtlessly articulate a valid objection to moving regulations to statute–what prevents an agency with a high affinity for rulemaking adoption (particularly those without formal legislative review) from simply ensconcing unnecessary regulatory capture into statute without a thoughtful analysis and review? In this data subset of seven executive branch agencies, the Idaho experience of implementing zero-based regulation and subsequently unwinding delegation moving regulations to statute resulted in eliminating 30,543 words from regulation and adding 5,405 words to statute, for a net reduction of 25,138 words.

Figure 1. Number of Pages of Regulation in Idaho Administrative Code (1996-2023)

While future research will provide Idaho state-level impact on an exact net regulatory reduction of ZBR, the ongoing efforts in Idaho suggest a 30-50 percent net reduction across all agencies. This is even after the state achieved a 75 percent net regulatory reduction “cut or simplification” in the 2019 Red Tape Reduction Act executive order.18 A prerequisite to unwinding delegation should also include an optimization process of executive-branch-led spring cleaning of sorts, taking out the regulatory trash. Zero-based regulation is one such example of cutting many regulatory strings before moving regulations to statute.

Conclusion

Instead of crafting detailed and clear legislation, state legislatures have delegated broad rulemaking authority to the unelected executive branch. The turning point on regulations will be when the legislative branch turns off the spigot of bills that delegate new authority to the executive. However, dismantling the administrative state must also include a strategic plan to untangle 50-100 years of regulations on the books. One particular mechanism of unwinding delegation could assuage concerns about the broad delegation of authority to regulatory agencies: well-established and change-infrequently, regulations that are suitable candidates to move to statute. Doing so provides the benefits of enhancing the stability of the regulatory environment, creating efficiencies that reduce overall regulatory volume, serving as a catalyst for broader policy reform, and saving on the overall cost of government. Further, it allows the legislature then to unwind delegations of regulatory authority either in whole or in part. Efforts to unwind delegation and move rules to statute can be agency-led or part of an overall regulatory reform strategy for a state–as recent legislation in Idaho has formalized.