Sunset and Cost Benefit Analysis Reforms in the State Regulatory Process

Introduction

Sound regulation relies on accountability, transparency, and reviewability. These desirable features of promulgating agencies are achievable at the state level through statutory changes to Administrative Procedure Acts (APAs). Specifically, states should start by encoding cost-benefit analysis requirements and sunset provisions into their APAs. These two crucial reforms discussed here foster responsible regulatory environments that encourage civic participation, reduce burdens on taxpayers and businesses, and stimulate long-term economic growth. By implementing these revisions, state governments can promote a sound regulatory philosophy and enhance expertise and transparency over time.

Sunset provisions mandate that rules expire and require that regulations go back through the state’s regulatory process and receive sufficient scrutiny to be reinstated. This way, regulations that cite laws that have been repealed or conflict with new laws or those that are merely obsolete can be removed, and the regulatory landscape refreshed throughout the review window. Reviewability is critical to rulemaking, yet many states stop short of comprehensive review requirements and do not obligate agencies to reconsider regulations automatically. Oftentimes, when rule review is conducted in the status quo, it is through the promulgating agency, with little to no third-party oversight and no incentive to meaningfully scrutinize the impacts and efficacy of the rule(s) in question. Thus, rules should automatically expire, require full re-promulgation and equal or greater justification for renewal, and review should occur periodically.

Cost-benefit analysis (CBA) is another staple of sound policymaking that is only sometimes incorporated into rulemaking. CBA allows policymakers to compare the expected benefits of a regulation against less speculative costs to ensure that the pros outweigh the cons. Unfortunately, many state rules are often drafted, approved, and enforced with minimal or no requirement for exhaustive CBA. If a CBA is conducted, it is most often done without clearly defined metrics, a holistic analysis of impacts across different time frames, or a stipulation that benefits exceed costs. Rule makers must carefully consider the cost borne by all regulated entities and the burden on the economy as a whole. Furthermore, citizens and regulated parties should be empowered with the standing to challenge regulations solely on grounds of flawed CBAs. For example, an aggrieved plaintiff should be able to challenge a rule in court if the actual costs exceed the actual benefits. Finally, CBA requirements and the analysis itself, including all underlying data and methodology, should be rigorously defended, statistically sound, data-driven, and made available and easily accessible to the public in an online and machine-readable format.

Background

The Role of Regulation in American Government

Historically, the role of regulation in American government has been to translate the nuances of law into everyday practice, adding clarity and definition to otherwise vague legislation. A law identifies issues in policy, markets, or elsewhere, defines outcomes for the federal government and citizens, and appropriates funding for solutions. The Clean Air Act of 1970, for example, authorized “comprehensive federal and state regulations to limit emissions,” and stood up a regulatory apparatus to handle the task, comprised of four regulatory programs that defined standards for emissions, among other things.1 This Act significantly expanded the enforcement authority, scope, and size of government. In the case of similar legislation passed concurrently, the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970 was so enormous that the federal government established the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and tasked this body with promulgating and enforcing rules ostensibly related to environmental protection.

Since the ’70s, legislators have increasingly abdicated authority to agencies in the executive branch through vague statutes, and regulations have grown increasingly expansive and onerous as a result. After the legislature passes legislation to solve a problem, their responsibilities toward that problem essentially cease and are placed upon the regulatory and enforcement agencies in the executive branch. This translation of power is the single most significant source of confusion and difficulty in the regulatory process, as agencies frequently and intensely regulate in a way that hampers economic outcomes and burdens citizens. However, the legislation would be largely toothless and unguided or unmanaged without regulatory agencies. The separation of powers present in The Constitution predetermines the role of the legislature and executive. However, over time, this relationship—between legislation and regulation—has markedly changed for the worse. As legislators increasingly delegate rulemaking authority and unelected agency bureaucrats grow increasingly powerful, it becomes necessary and prudent to reform processes related to rule promulgation and continuation.

Regulatory Problems

Regulatory Proliferation

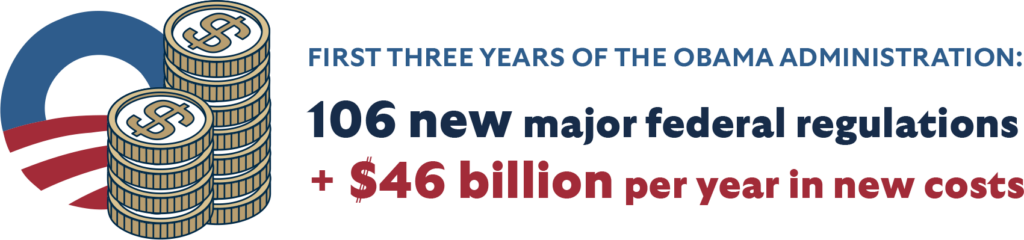

The U.S. Code of Federal Regulations has grown by more than 20 percent since 1997 and now contains 1.08 million instances of restrictive language.2 This regulatory accumulation substantially stifles the economy and has slowed growth by 0.8 percent annually since 1980.3 On the contrary, “If regulation had been held constant at levels observed in 1980, the US economy would have been about 25 percent larger than it actually was as of 2012,” translating to an increase of $4 trillion or a loss of $13,000 per capita.4 Comparatively, the federal deficit in 2012 was $1.1 trillion.5 This is devastating to the economy and the American worker, who often rely on sustained growth for economic opportunities such as better job prospects and wage growth. In the first three years of the Obama administration alone, “106 new major federal regulations added over $46 billion per year in new costs for Americans.”6 The administration added 32 new major regulations with an annual cost of nearly $10 billion and another $6.6 billion in implementation costs.7 Accumulating regulation undermines the American economy, disproportionately harming the average American worker, and results in future losses measured in trillions of dollars.

Unfortunately for these workers, federal regulations are only one piece of the problem. Small businesses must navigate these tremendous federal hurdles and endure the costs of state regulations, further stifling growth and innovation. Sunsetting is a crucial first step to reducing this mammoth regulatory burden.

Most states still need to codify a regulatory sunset, or their existing sunset procedures are limited and ineffective. One example is Utah. Although Utah’s state code calls for every regulation to expire one year after going into effect unless reauthorized by the state legislature, the reauthorization process is omnibus. It only requires the legislature to specify which rules will not be reauthorized and subsequently demands a justification for any repeals.8 This process falls short of a comprehensive review of regulations, perpetuating outdated rules.

When a rule is created without an expiration date, it is unlikely to be reviewed, resulting in a lack of accountability and unnecessary deadweight economic losses. Without a review process or automatic expiration, agencies have little incentive to address problems in their regulations, and these potentially burdensome regulations stay on the books indefinitely. Permanent regulations hamper efficiency, as old and inflexible regulations lock in practices that may otherwise become obsolete.

Several undesired results occur without a sunset provision, four of which stand out: 1) outdated rules, 2) agency overreach, 3) unaccountable rulemaking, and 4) regulatory proliferation.

First, some regulations outlive their useful life. In states without a sunset provision, these rules are unlikely to be removed; instead, they are locked in from the moment of publication. Without any mechanism to ensure review, it is doubtful that any regulation will ever adapt or be updated to meet dynamic environments across the regulatory landscape. A rule effective in 2010 will likely be costly, outdated, and ineffective in 2030, yet still enforceable. Without any incentive to create forward-thinking regulations—and with thousands of rules—agencies are unlikely to write narrow, specific regulations and will instead engage in runaway rulemaking.

Second, without sunset provisions, agencies have more freedom to create regulations that are inflexible, lack measures to account for the future, or will deliberately promulgate regulations that inaccurately predict the actual cost of compliance for regulated bodies, whether they be businesses, consumers, workers, or the overall economic environment. In regulatory climates where periodic review is nonexistent or irregular, agencies are not compelled to draft tailored, specific rules or able to stand the test of time. Without sunset provisions, agencies have little to no incentive to reconsider a rule in any context other than the one in which it passed, resulting in inflexible regulations. While a once-efficient regulation can become inefficient, worse still is regulation that is inefficient from the start. Without a sunset provision in place, regulated individuals and businesses bear costs much larger than any estimate may foresee, particularly if the regulating agency itself undertakes that estimate; worse still is the possibility of regulation that imposes a high cost of compliance without accomplishing its stated goal.

The third consequence is that regulatory bodies and their rules become unaccountable when not subjected to periodic review. While some states have experimented with a kind of sunsetting policy, the sunsetting was targeted against entire agencies, but did not consider their rulemaking processes or specific rules. This agency sunsetting can only act as a check against small and specific agencies, such as a regulator of a particular type of industry (e.g., the barbering licensing body). Once, say, the mining operation leaves town, the agency can sunset, and all is well. When this same style of sunsetting is applied to agencies as large and potent as the Department of Transportation, for example, it becomes clear that this version of sunsetting is suboptimal and historically is likely only to result in primarily small procedural recommendations. What this less-than-ideal form of sunsetting does provide, however, is evidence of a demand for oversight of executive agencies.

Finally, unless held accountable, agencies will continue to proliferate new regulations as they see fit without consideration of the long-term economic ramifications. This regulatory proliferation leads to increased regulatory bloat and unnecessary economic burdens. Administrative bureaucrats continue to proliferate regulation, which, when accumulated, results in severe economic burdens.

Lack of Accountability in Cost-Benefit Analyses

Cost-benefit analysis (CBA) is a tool used by state governments and legislators to determine the impact of a specific rule or regulation before it is passed. The CBA is usually conducted by either the agency promulgating the rule or the job is passed on to a third party chosen by the state government. The CBA looks at the impact the proposed rule would have on small businesses and individuals, what the costs would look like in the short and long terms, and if the benefit of the rule would outweigh its costs.

Currently, most states across the U.S. have some sort of CBA process outlined in their APAs or state constitutions. However, most states do not outline or mandate clear standards on what constitutes a cost or a benefit and how to quantify each element.9 At the federal level, cost-benefit analyses have been honed for decades, with reasonably clear guidance set forth by consecutive administrations across party lines. Regulatory experts working at the federal level often assume this is the case for state-level rulemaking—but some states lack cost-benefit analyses entirely or have only limited requirements for analyses in rulemaking. Not having a proper CBA is an insufficient incentive for agencies to create rules that are not future-proofed and do not consider real impact measurably. Few states require agencies to look back and assess the rule’s impact. When analysis is conducted, it is often not standardized, made transparent, or available to the public. It typically lacks a requirement that the benefits of a proposed regulation outweigh the costs.

Small businesses and individuals in many states have limited say and impact in the rulemaking process, even when the rule directly impacts their business. When cost-benefit analysis is conducted, citizens frequently lack the right to challenge a rule during promulgation based on said analysis alone. When stakeholders post comments voicing concerns regarding CBA and potential adverse outcomes, agencies are often not required to amend the rule in light of the comments, resulting in stakeholder input falling on deaf ears.

States are implementing inflexible, burdensome rules that are not subject to regulatory review after they are passed, leaving old, outdated, expensive regulations in place. Yet these more controversial regulatory issues—populating the headlines—often represent a small quotient of the problem. Fundamentally, bad or non-existent cost-benefit analysis in rulemaking has longterm impacts on America’s overall economic health.

Policy Solutions

Sunset

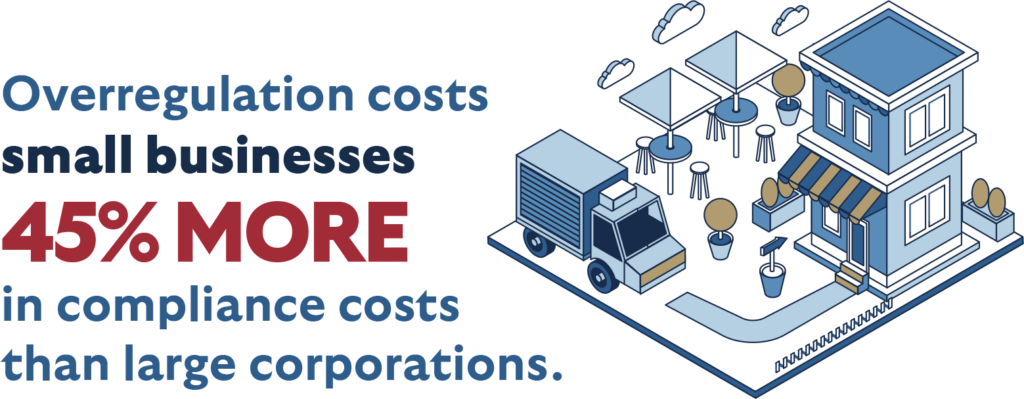

Overregulation pushes commerce into the shadow economy, stifles innovation, and costs small businesses 45 percent more in compliance costs than large corporations.10,11,12,13 The Cicero Institute aims to restore free-market incentives, correcting upstream regulatory incentive structures that disproportionately favor special interests and cause market inefficiencies. Mandatory regulatory sunsets, with a nuts-and-bolts approach to government, increase accountability and efficiency over time, steadily actualizing free market principles by creating room for businesses to operate successfully and safely.

Sunsetting effectively reduces regulatory burdens at the state level and does not need to involve a blanket revocation or cancellation of regulations currently on the books. Instead, it seeks to eliminate harmful regulations and replace outdated regulations with fresh updates powered by stringent periodic review and civic participation through the notice and comment process explicitly designed to avoid rubber-stamping old or obsolete rules. A regulatory sunset is, therefore, a structural reform that automatically nullifies harmful regulations after a predetermined time frame. The result is a process that shifts burdens, requiring agencies to justify the continuation of existing regulations. Indeed, “even well-intended, seemingly efficient, regulations can create unforeseeable outcomes, unintended consequences, or secondary effects that are only known once the regulation is in force.”14 States must have a process that forces regulations to be reviewed and subsequently refined or entirely reconsidered.

The level of scrutiny on existing regulations and the justification required to maintain a regulation can be increased through sunset review provisions. These review provisions work the same way as agency sunsets but with an increased onus of justification upon re-introduction. Sunset review provisions are various quantifiable metrics that show whether the regulation is achieving its stated goal most cost-effectively. Sunset review provisions can also include renewed opportunities for public comment, allowing affected parties to voice their suggestions or concerns with the regulation. This mandated review process will enable agencies to understand better whether their hypotheses have proven effective or ineffective. With data, such as five years’ worth of active regulatory results, an agency will be able to tweak the regulation to be more effective or choose to scrap it entirely.

Regulatory sunset reforms should include the following provisions:

Periodic expiration of rules, which must thereafter undergo the entire rulemaking process, including notice and comment again before reinstatement. This expiration should occur on five-, 10-, or 15-year timelines based on the rule’s publication date. For example, a rule created in 2030 would expire in 2035 and be reinstated only after a full re-promulgation.

Comprehensive sunset review provisions should also include: (a) a renewed cost-benefit analysis, calling upon data from the regulation’s time in effect; (b) an opportunity for accountability through a public comment process, usually consisting of a 30-day window in which affected parties make known their concerns or suggestions for the regulation; and (c) a comprehensive review of whether or not the regulation has been effective in achieving its stated goal until that point, an analysis of if the regulation can be refined or simplified, and; (d) if the goal can be accomplished in a manner other than regulation, such as a tax.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

Implementing new CBA rules and creating a standardized way to measure the costs and benefits of a proposed rule can help reduce the unnecessary regulatory burden on small businesses. A good CBA should include clear, concise, and easy-to-understand data-driven analysis and a standardized measure of costs and benefits. The data should be converted into a monetized cost-and-benefit model when possible.

States across the U.S. implement these policies differently, but no one state uses all. For example, the Texas APA defines a cost and benefit as clearly outlined.15 The Washington State Institute for Public Policy, the organization that conducts Washington’s CBAs, publishes a monetized model for each of their CBAs, including benefits or costs to taxpayers and the state government.16

States should have a periodic review in place and implement a second CBA as part of that periodic review, drawing comparisons to the original. From this exercise, the state agency may determine whether the original analysis is accurate and amend, refresh, or promulgate a new rule that addresses this discrepancy. Cost-benefit analysis can be effective when implemented with or without periodic review. However, having a CBA at promulgation and again down the road enables agencies to draw lessons from their past performance.

Monetization & Quantitative v. Qualitative Analysis

Monetization, as used here, refers to the quantitative assessment of costs and benefits in dollar value. It is presented in opposition to qualitative costs of benefits, which might refer to non-dollar values. In state-level regulatory analysis, it can be problematic to assume qualitative values where monetized values can be determined or utilized. Converting all costs and benefits to dollar values allows for the true cost of regulation to the stakeholder to be assessed accurately. Monetization is common practice in regulatory promulgation, but there are often no requirements for the monetized values to be exclusively used or highly prioritized over qualitative data. Agencies should be limited in their ability to derive qualitative benefits, which they might claim outweigh monetized costs. This means agencies must assess if they can prove that a monetized benefit is quantitative and can be monetized without becoming problematic. Stakeholders need reliable analysis that shows them the costs of a regulation and its benefits in dollar values, which match their businesses’ functionality as a balance sheet. Still, this process should include some guardrails that prevent wobbly conversions of qualitative benefits into monetized values.

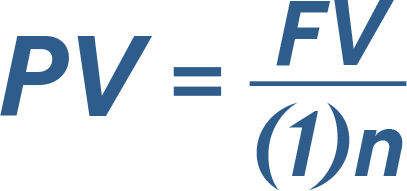

Additionally, qualitative benefits are at risk of overinflation and are ambiguous and tenuous. Costs can be monetized using present values. If a regulation is proposed that would require all food trucks in Austin, Texas, to have a six-foot awning for sun protection, the agency would need to identify the cost to retrofit a food truck with the awning, then multiply that cost by the number of registered food trucks in the city. This is known as a quantitative assessment and can easily be monetized by using dollar values for the present cost. To calculate the present cost, the agency would utilize the following formula, where all costs equal dollar values as follows:

Here, PV represents the present value, FV is the future value, and n is the number of years from the present.17 For the example used above, agencies could calculate separately the cost to retrofit all trucks currently registered as one cost analysis and then conduct a separate study to assess the cost over time, which would represent the added cost of compliance for new food trucks. This calculation does not include discount rates or account for inflation.

Discount Rates

A dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow. This is known as the time value of money. In regulatory economic analysis, the discount rate represents the time value of costs or benefits. This is typically represented as a percentage, meant to adjust the analysis to loosely track risk-free market investment interest rates and gauge the rate of return on capital and consumption.

Consumption Rate & Capital Rate

On consumption versus investment rates of interest, research from The Mercatus Center states, “the consumption rate of interest is used to discount resources that are consumed, and the investment rate of interest applies to resources that are invested,” marking a distinction between financial assets and real resources outside of capital such as fuel or grain.18 Cash is discounted due to the time value of current investments, which will always exceed future investments. If the government takes money from a business today through taxation or regulation, the cost is more than the exact value charged due to the opportunity cost of that business not investing the money elsewhere, where the marginal rate of return to capital can be assumed. While an investment rate applies to capital returns–often considered compounding owing to reinvestment potential–the consumption rate is used to gauge costs and benefits to a household or consumer as a unit of consumption. Generally, these two rates are used separately to arrive at two distinct cost and benefit conclusions during analysis to show how a regulation might affect different groups and assets.

When considering compounding interest rates on costs or benefits, it remains critical to parse those exact costs or benefits and apply compounding principles only where appropriate. Analysts should strictly avoid attempting to project compounding interest to rates that do not tangibly compound at the marginal rate of return to capital. If, for example, a policy is proposed that reduces asthma rates in children at a specific cost per child, the benefits of not having asthma would be both tangible and intangible. For one, the children would be happier, and their families would as well. Still, the burden those children would have financially on the healthcare system, especially if they receive care under the Affordable Care Act or their care is otherwise subsidized, would be eased. This benefit, should it be $10 per child, should not be subject to compounding at the marginal rate of return to capital. Cost-benefit analysis in this example would conclude that it is only beneficial financially if the reduced burden on the healthcare system exceeds the cost to taxpayers. Yet we still might all agree that the policy is worth pursuing to help children and improve the quality of life of Americans. This mismatch between financial costs and benefits and those that cannot be directly tied to dollar amounts creates tension in the cost-benefit analysis process.

Monetization is an essential tool designed to compare the analysis to a balance sheet and show the actual cost or benefit of a regulation to a business. In the previous asthma example, presenting the benefits of reducing asthma as a value of dollars saved by the healthcare system would be savings conveyed directly to the taxpayer. Time, such as labor, can be represented in wages. Some costs and benefits may be complex and difficult to monetize. Suppose the government wishes to increase food security through farming advancements. In that case, they may set a standard, in the form of a regulation, for things such as grain silo storage, materials, and maintenance. These increased materials would come with a market-determined dollar cost, as would the labor required for installation—which may be more intensive in hours or skill—both would be dollar-value costs to the farmer.

Benefits that could be easily monetized include increased storage life of grain and increased silo lifespan, represented as dollar values. A complexity would involve the risk factor of the silo integrity, expressed as a percentage of likelihood, rising as the silo hull ages. If the agency has been tracking data related to the costs and benefits of regulation or proposed regulation for some time, they might include in their analysis the previous amount of silo breakage under the current regulation. The agency could claim their analysis that a reduction, represented by a percentage, in issues with the silo, which cause grain loss and construction costs, would benefit farmers and consumers while boosting tax revenues on the extra grain. If the benefits are significant, such as the near elimination of grain loss, the agency could claim this benefit outweighs the cost and include a subsidy for materials to qualifying farms, including that potential cost in their analysis. In this example and otherwise, cost-benefit analysis is critical to aiding, informing, and guiding agency decisions, allowing them to stand behind regulations they promulgate confidently and enabling the public to understand and challenge regulation more effectively and with increased competence.

Current and Proposed Discount Rates

Federal cost-benefit analysis determines rates used by the White House Circular A-4, which states a three percent consumption rate and a seven percent capital rate. Both benchmarks were decided in the 2003 Circular A-4 by tying the rates to free market, risk-neutral returns. The seven percent figure, or capital rate, represents the capital returns in the stock market. The three percent figure, or consumption rate–sometimes referred to by economists as the consumer rate–means the return received by consumers, a number calculated in 2003 by averaging the three-decade yield on 10-year Treasury securities and accounting for inflation.19–20

Lower rates more accurately determine costs in the future and show more benefits up front, with the reverse being true for higher rates.21 Many scholars have called for rate changes inversely based on calculations they have made to justify a specific policy position; the rate would need to be lowered or raised, for example. The Circular A-4 explicitly sets rates to prevent this, but rates still need to be revised. They serve a specific function in federal cost-benefit analysis, but no document governing discounting exists in a typical state regulatory environment. Therefore, states will be tempted to adopt either another state’s discount policy or the federal guidelines in their analysis.

Short Term Discount Rate Avoidance

Federal regulation often involves intergenerational timelines for analysis that reach deep into the future. The further a regulation reaches the future, the more critical a proper discount rate becomes in determining costs and benefits. For state-level cost-benefit analysis, states should carefully consider the use of discount rates entirely. In a healthy regulatory environment, regulations will either expire or undergo review periodically and frequently, and cost benefits will be conducted at promulgation and again during review. Under these circumstances, discount rates should be avoided entirely. Rather than fixing discount rates to capital and consumption market returns–where the far-reaching impacts of regulation are estimated and modeled to the best of the agency’s ability, and then the regulation is put on the books and left untouched in perpetuity–agencies should forgo discount rates entirely in favor of estimating immediate and short-term costs and benefits and reviewing those analyses frequently, such as every five years. This prevents agencies from justifying burdensome costs now by promising benefits that might be decades away—or even intergenerational. By forgoing discount rates entirely, state agencies can focus on the costs to consumers in the immediate present and the next few years and adjust regulation more frequently, resulting in better regulation that reflects the current economic realities—whatever they may be.

Policy

Cost-benefit analysis should address the following:

- Require stringent cost-benefit analysis for all rulemaking.

- With few exceptions, every rule drafted and proposed should undergo a stringent cost-benefit analysis. Any agency claiming that regulation will benefit the economy or citizenry must defend its claim with transparent and robust analysis. Analyses should be data-driven and standardized across all regulations.

- Require bureaucrats to carefully consider the cost to regulated entities and the burden on the economy in all sectors or industries the regulation touches.

- Agencies should identify the stakeholders affected by a proposed regulation and assess the costs and benefits to each to determine any issues with disproportionate costs to stakeholders. A regulation that benefits a larger corporation may stifle competition at the small business level, where innovation often occurs. A farm bill that might help large farms could have unforeseen externalities such as costs to small farmer co-opts or otherwise.

- Require that costs do not exceed benefits.

- Regulation should be beneficial to Americans and not costly. Any costs incurred should be justified for safety or necessity but generally minimized where possible. Comprehensive CBA should be used to identify issues with regulations regarding their balance of cost and benefits, not simply serve as a calculation.

- Empower citizens to challenge the proposed regulation solely because the actual costs exceed the actual benefits.

- Citizens should have the right to challenge a proposed regulation because the costs outweigh the benefits to them or others as stakeholders. This challenge right would force agencies to hear and adjust rules accordingly.

- Ensure public access to data that supports the CBA so the public can scrutinize a regulation.

- Analysis should be transparent, machine-readable, readily available, and easily accessible to the public. Data, methods, techniques, and other materials should be published on an agency website that does not require login or credentials to view. The complete and comprehensive analysis should exist there, unabridged, for the public to view and download for their own use.

- Mitigate the use of discount rates in longer-term analysis.

- Discount rates are often problematic and result in inaccurate economic forecasting and modeling. They should be limited to a smaller time frame, such as five or 10 years.

Outcomes

Economic Benefits

Regulations are, at their core, restrictions the government places on businesses and the economy writ large. Removing these restrictions responsibly, and in some cases replacing them with improved restrictions, has demonstrable benefits. Over time, as regulations accumulate, so does their life support system, which is the administrative state. The result is an increase in budget and staffing for regulatory agencies, growing year by year with the budget. Since 1960, federal agency regulatory budgets have increased 14 times at the federal level, with staffing closely following at close to six times.22

The compliance costs are not solely for the regulated to bear; the government must also assume the enforcement and administration costs. Burdensome regulations add on costs for a new home or car, but they also cost money themselves to enforce and administrate. While we might accept adding staff to a regulatory agency to conduct a comprehensive review or cost and impact analysis, adding staff every year to create and enforce more regulations is not productive. The taxpayer pays this cost, manifesting itself in increased prices and growing tax burdens.

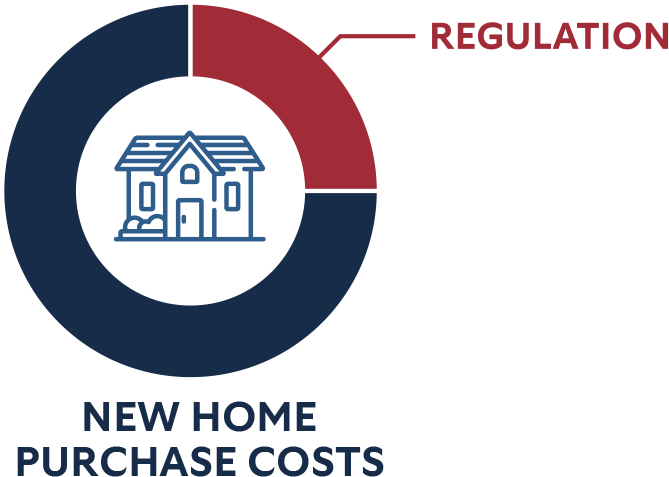

When the prices of goods and services increase because of regulation, it becomes increasingly difficult to maintain the same quality of life, and Americans suffer. An increase in costs represents a decrease in opportunity for Americans. For example, costs associated with regulation comprise close to 25 percent of a new home purchase, or around $95,000.23 The more expensive the house, the more regulatory costs the buyer can expect. Regulatory costs associated with single-family real estate doubled under the Obama administration and have marginally increased since 2016. Unfortunately, the same is true for automobiles, with regulatory costs reaching close to $7,500 for a new vehicle.24

Housing and automobile regulations contribute to increased safety but also higher prices, and when combined with state-level regulations that vary highly and are not subject to proper cost-benefit analysis or periodic review, the result is a growing wealth gap. The number of Americans who can no longer afford a house or car is, in fact, growing, and regulation—something over which the state has complete control—can either contribute to or help alleviate that critical issue. Regulatory agencies and their proponents often point to a regulation’s proposed or perceived benefits, but few attempt to cover the opportunity cost of that regulation—what we lose by regulating. Instead of dealing with a compliance burden, companies and smaller businesses would be able to invest personnel and capital assets into more profitable operations. These resources may also be directed towards new and exciting innovations, making products more efficient and cost-effective. The least-regulated sectors of the economy are often the emergent ones, as the administrative state has yet to choke them out. This is evident in the proliferation of several key markets in the recent past, such as social media, early dot com success stories like Amazon or Google, or television before them.

Innovation is difficult to model or anticipate, but we know that when regulatory burdens are minimized or responsible regulation thrives, and so does innovation. New ideas and products help push our economy forward and provide growth in new directions. Often, regulatory guard rails meant to protect consumers end up limiting producers to the extent that innovation is stifled, as the only profitable product becomes the one the regulators approve of. Shifting state regulations towards fewer regulations, leaving only those who have been thoroughly analyzed and whose benefits generally outweigh costs, can help alleviate burdens and get our economy up to full speed.

Civic Benefits

Better regulation backed by better data and methods, including review, helps foster responsible governance and creates a better dynamic for citizens. Rather than maintaining an adversarial relationship between an agency and regulated entities or the citizenry, good regulation from an agency that works with the citizenry fosters a good government, and everyone benefits. Many regulations can be beneficial and have long-term benefits. Still, citizens should always have the right to participate fully in the regulatory process, guiding agencies to regulations that benefit rather than harm them. Sunset provisions and cost-benefit analysis requirements provide this service to the worker by creating sound rather than burdensome regulations. The economic benefit of reduced costs also translates to a civic benefit in that the money saved can be reinvested into businesses and the community.

Sunset

The sunset schedule can be seen as a periodic review of existing regulations: because the rule will automatically expire, agencies are incentivized to write more refined regulations, increasing flexibility in the regulatory environment. This process will be abetted by the tangible data gained during the period of active regulation. A regulatory sunset also creates accountability through public participation in government, allowing the public to be involved in the renewal process and resulting in old, outdated, and inefficient regulations dying off.

Regulatory sunsets and sunset review provisions would also benefit the business environment at all levels. Having an over-regulated business sector stifles entrepreneurship by raising the barrier of entry, therefore benefiting large enterprises that can bear the increased cost of a regulatory burden more than a new small business.25 Decreased competition is destructive for the entire industry—as it is often emergent—and small enterprises that experiment with innovations and methods for increased efficiency. A sunset review provision would measure whether the regulation created an unnecessary cost for businesses and if consumers are paying an excessive direct or indirect cost.

Another benefit of regulatory sunset provisions is political accountability. If a political actor or agent within the executive branch institutes a regulatory policy, until there is a comprehensive study to determine whether it has been effective, they can take credit for the regulation on the assumption that it has succeeded in achieving its goals. Additionally, agencies can do the same, drafting regulations continually without any requirement to go back and review those regulations for efficacy. A regular sunsetting period will hold agencies and other regulators accountable by determining their regulation’s accuracy and success rate, especially with sunset review provisions, which can produce factual results after some time in effect.

Counter Arguments

A counterargument to regulatory sunset provisions is that the re-approval process diverts energy and resources away from active governance and towards constantly re-justifying existing regulation. This argument is reductive and ignores the savings incurred by reviewing and eliminating outdated or burdensome regulations. Studies have found, for example, that Texas’s regulatory sunset provisions saved the state $27 for every $1 spent on review; in Minnesota, it was as high as $42 saved for every $1.00.26 When regulations are rubber-stamped in renewal rather than being comprehensively reviewed and updated or eliminated, it results in old and outdated rules that can impose costs on an ever-changing economy. Regulations need to be current and reflect the demands of the economy as they exist today—not as they existed decades ago—and review requirements should exist to address this problem and ensure up-to-date, lean, and effective regulation.

Another counterargument to regulatory sunset is that it allows for regulatory capture. Critics claim that the blanket elimination of regulation enables bad actors to step in and affect the promulgation of new rules in their favor. This argument fails in two ways. First, the underlying issues, or strengths, must be addressed in the promulgation process. With proper cost-benefit analysis requirements, sunset provisions that enable periodic review, and healthy regulatory planning from the governor’s office, it seems less likely that the regulation created to replace an expiring one would be captured. In a system without these regulatory reforms, regulatory capture will occur regardless of sunset provisions. The immediate goal of the sunset provision is to compel agencies to review and revise outdated regulations to create leaner and more efficient regulatory environments. Doing so decisively reduces capture.

Cost-benefit analysis

Sound cost-benefit analysis has three primary benefits. First, it helps avoid costly regulation by identifying it through analysis. This reduces the burden on taxpayers and businesses through the resulting better regulation, but it also allows agencies to learn from the analysis. When agencies promulgate regulations without due diligence, they miss the opportunity to take stock at promulgation and again later during the review, missing the chance to build institutional knowledge about how their regulatory philosophy translates to the consumer.

Second, agencies can further justify those regulatory philosophies through sound analysis rather than stating proposed benefits without supporting their claims. Citizens need to be able to challenge regulations and be heard during promulgation. Better yet, agencies challenge themselves by interrogating their regulatory philosophy and leveraging data-backed analysis to make better decisions. As time passes, agencies will develop lessons learned, which they can use to promulgate increasingly sound regulation. When challenged by citizens or governments, agencies can confidently rely on their analysis and point to where their philosophy is supported rather than being forced to defend their rulemaking in a vacuum.

Third, transparent and data-driven cost-benefit analysis enables civic participation and engagement through input directly tied to that analysis. When citizens can challenge a rule during promulgation based on the cost-benefit analysis alone, it allows an additional avenue of civic engagement. Increased civic engagement results in better government, reaffirming the core principles of our Republic. Agencies should encourage this and be excited about working with stakeholders to draft regulations that benefit everyone, not just rules that support the agency’s mission.

Counter Arguments

Similar to sunset provisions, critics are quick to claim that required or increasingly stringent cost-benefit analysis will balloon agency costs, requiring more time and personnel than they can afford. Agency heads may counter by claiming those new requirements must come with a larger budget for staffing and training. This counterargument fails in several ways. First, it fails to consider the financial benefits translated to the consumer through fewer burdensome regulations, leading to economic growth and increased tax receipts. Second, and more importantly, agencies should always introduce sound, data-based research and analysis into their decision-making processes. Current agency full-time employees promulgating rules without sound analysis should be redirected to cost-benefit tasks, slowing the agency down and resulting in fewer—but better—regulations. Emergency exceptions exist to accommodate those regulatory needs that arise and may require a faster response from the agency. Those regulations would be subject to review after some time, at which point they would receive their own cost-benefit analysis.

Implementation Strategies

Executive v. Legislative Solutions

When implementing regulatory reform, policymakers and experts have two general avenues to approach issues. The first is to generate a bill encompassing one or several reforms and likely targeting a large swath of regulatory reform. The resulting legislation will codify that reform into statute, amending the APA and instructing further regulatory efforts through the authority of the state congress. The second approach is to reform regulation through executive order, which has widely varying outcomes based on the intent of the executive office, their regulatory planning goals, and the state’s political environment.

In his 2021 paper titled “The Impossibility of Legislative Regulatory Reform and the Futility of Executive Regulatory Reform,” Stuart Shapiro examined federal regulatory reforms focusing on the executive. He found that most executive reforms have been ineffective apart from those of the Clinton and Trump Administrations.27 Even if the executive effectively reforms regulation, doing so through executive order does not provide a long-term solution. This concept is echoed at the state level as state regulatory reforms from the executive will face similar issues in the long term. Additionally, states that rely on the executive entirely for regulatory process risk accountability in review. Despite this, executive reform remains an option when legislative reform is not tenable.

While these executive reforms are at risk of elimination when a new or adversarial executive assumes office years later, they still offer targeted, potent reform options for states to implement. Shapiro was commenting on federal regulatory reforms, but executive reform has proven effective at the state level. Executive reform is most robust when coupled with an independent review agency under close watch from the Governor’s office. Such agencies exist in Virginia, Arizona, Montana, and other states in which the governor’s office directs specific regulatory reviews covering analysis, promulgation, and even sunsetting or periodic review. Executive reforms can be impactful in states where the Executive is on the same page as the Legislature. Still, they may also be an option where discourse exists between branches or chambers.

Sunset

Idaho

Idaho has had great success in regulatory reform using sunset provisions. In a single year, Idaho eliminated or simplified 75 percent of the 72,000 pages of rules and restrictions they had in effect.28–29 To prevent the same regulatory bloat from returning, Governor Brad Little instituted a five-year regulatory sunset provision requiring state agencies to review 20 percent of their regulations annually. If, after review, the agency wishes to maintain a rule, the sunset review provisions require the agency to conduct a “retrospective… critical and comprehensive review,” which does not “simply reauthorize their existing rule chapter.” Instead, the agency must “determine whether the benefits the rule intended to achieve are being realized, whether those benefits justify the costs of the rule, and whether there are less-restrictive alternatives to accomplish the benefits.”30

Cost Benefit Analysis

All U.S. states have varying models for how they conduct, use, and implement CBA into their rulemaking process.31 Some states are willing to invest more resources in their CBA process; however, their efforts are often misguided due to a lack of accountability.

Washington

Washington has an in-house institute, the Washington State Institute for Public Policy (WSIPP), which conducts CBA for the legislators and agencies.32 This is a state-funded organization that conducts CBA on rules that are being promulgated and looks back at regulations that have been passed. The WSIPP conducts studies as directed by the legislative body of Washington State. The CBA looks at the current and future costs of a rule and the immediate and long-term benefits in both quantitative (monetized) and qualitative terms. The WSIPP has a website where the public can look at the reports and data from any of the CBAs they have conducted. However, legislators or agencies in Washington are not required to change a rule draft if the long-term or short-term costs are higher than the benefits of a specific rule.33 Even when state governments try to implement a good CBA process, there continues to be a lack of accountability and use of the information.

Virginia

Under Governor Glenn Youngkin, the State of Virginia has implemented executive regulatory reform to great effect. Executive Order 19 established an Office of Regulatory Management, tasked with reviewing regulations, sunsetting bad regulations and implementing a standardized cost-benefit analysis regime. The office issued a handbook on regulatory analysis and cost-benefit analysis to allow agencies to standardize the process as they did. The EO also calls for agencies to submit two less-costly alternative regulations. For each regulation proposed or under review, the office looks at all analyses and alternatives and decides which rule to implement. As detailed on pages 9 and 10, Virginia’s standardized cost-benefit analysis model works well and allows agencies to limit economists on staff—a labor requirement that can be demanding for smaller agencies. Additionally, the EO called for a 25 percent reduction in overall regulation, which they have far exceeded.

Conclusion

Good regulation relies on accountability, transparency, and reviewability—desirable traits for promulgating agencies. States should seek to implement regulatory reforms through the cost-benefit analysis requirements and sunset provisions discussed here. In doing so, they will foster responsible regulatory environments that encourage civic participation, reduce burdens on taxpayers and businesses alike, and stimulate economic growth while enhancing their regulatory philosophy and agency expertise transparently and soundly. States with some component of sunset or cost-benefit reforms can seek to implement all or part of these reforms to complement their existing systems. Better regulation backed by better data and methods, subject to review, helps foster responsible governance and creates a better dynamic for citizens.

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about our fight for policies at the state level that restore liberty through transparency and accountability in American governance.