Sex Offenders: An Overlooked but Significant Subpopulation of the Homeless

Executive Summary

The homeless population in the United States is very diverse. Over the last decade, scholars have made considerable progress in advancing our understanding of the various subpopulations and the myriad drivers of homelessness that are associated with each. But even as researchers have found a history of criminal offending in a sizeable proportion of homeless people, analyses of criminal history and homelessness remain simplistic and underdeveloped. Homeless sex offenders present a special case of interest within this subpopulation because of their unique set of social and legal barriers to housing and their risk profile, which is exacerbated by homelessness.

This study investigates the prevalence of homelessness among registered sex offenders in 41 states and, in turn, compares those findings to state-level homelessness data from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to determine the extent to which sex offenders are a prominent subpopulation of homelessness. The use of Point-in-Time Count data, which is known to undercount unsheltered homeless individuals, creates many limitations to the results, but given the PIT Count’s use by officials, it still provides useful information to policymakers. The results of this study indicate that more than 10 percent of unsheltered homeless populations are registered sex offenders in 32 states, and more than half are registered sex offenders in eight states. As a proportion of total homeless populations, only nine states had more than 10 percent registered sex offenders. Median results for homeless sex offenders were higher than those of all HUD-tracked unsheltered homeless subpopulations selected for comparison and were similarly sized to all but two of the HUD-tracked total homeless subpopulations selected for comparison. No geographic patterns were tested conclusively, but results show some evidence of higher proportions of sex offenders among unsheltered homeless in the Midwest, northern Mountain West, and Southern New England. The results of this study should inform policymaking and practice in states where sex offenses are a sizeable subpopulation, as this population has several distinctive risks and needs that may not be well addressed by conventional homelessness interventions. Moreover, this study aims to spur additional research into the connection between sex offenses and homelessness, especially in relation to public safety implications and potential drivers of the variability in homeless rates of sex offenders among states.

Introduction

The U.S. had 771,480 homeless individuals living in shelters or on the street, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) delivered to Congress at the end of 2024.1 The report showed homelessness has increased across subpopulations, with nearly every category reaching record levels.2 These increases held across geographical regions as well, with all but seven states seeing a rise in the number of homeless people.3 As America’s homelessness crisis worsens, scholars and policymakers alike have sought a better understanding of homeless people and the reasons they may have become homeless.

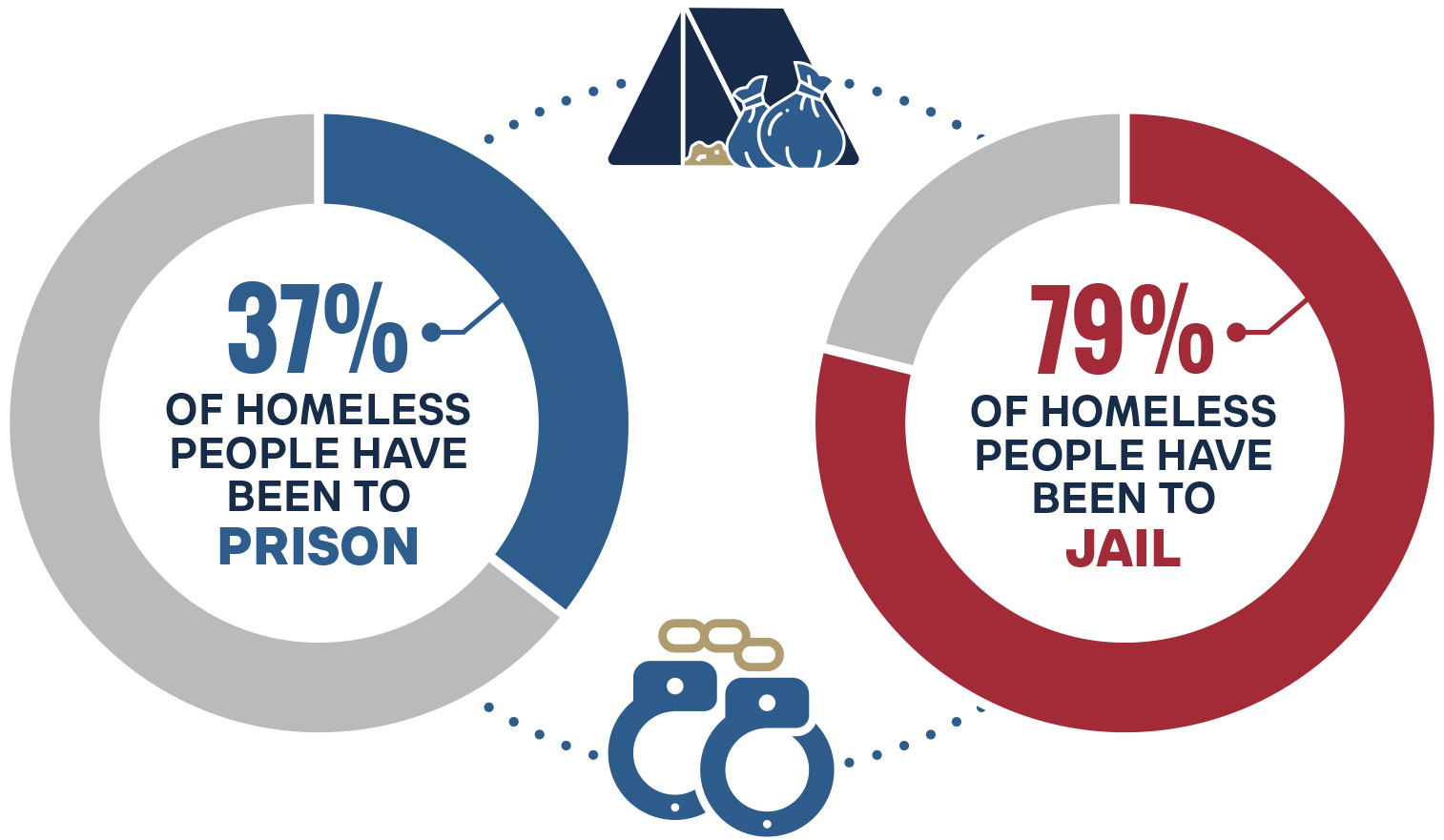

One of the largest studies of homelessness to date, Kushel et al. (2023), surveyed 3,200 homeless people in California and interviewed more than 300 to understand the backgrounds of homeless individuals better.4 The findings were remarkably diverse, indicating that homeless people come from a broad cross-section of society and end up homeless due to a variety of economic, social, legal, and personal factors.5 There was, however, a surprisingly consistent theme that the report found, but did not explore in as much depth: incarceration for criminal offenses. Kushel et al. (2023) found that 37 percent of homeless people had been to prison in their lifetime, and 79 percent had been to jail.6 One in five had entered their recent episode of homelessness following a prison or long jail sentence. But many were also victims of crime—half reported physical or sexual violence, with 15 percent experiencing sexual violence specifically.7 Yet, even in this exploration of criminal justice involvement, very little nuance was afforded to different types of criminal offenders or how that could impact their loss of housing or ability to attain new housing successfully. In particular, sex offenders, who arguably face the steepest personal, social, and legal barriers to housing and reintegration after prison, were not even mentioned in the report.8

Very few homelessness advocacy and research centers have given sex offenders attention. The research databases of the National Alliance to End Homelessness, the Homelessness Policy and Research Institute at the University of Southern California, and the Initiative on Health and Homelessness at the Harvard Chan School of Public Health do not contain a single reference to sex offenders or the restrictive policies they face in finding a place to live. The database at the Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative at the University of California at San Francisco turns up only one result from a search of the term “sex offender”—a blog post about potential sex offense prosecution for public urination.9 Though a commonly held misconception, it is extremely rare for an individual to be prosecuted and placed on a sex offender registry for public urination.10

While homelessness scholars have largely ignored the connection between sex offenders and homelessness, criminologists have not. Harris, Levenson, and Ackerman (2014) found that two to five percent of the nation’s registered sex offenders are homeless, a significantly higher rate than that of the general population, which sits below one percent.11 But even that measure masks the true relevance of sex offenders to homelessness research and policy, as it captures the proportion of sex offenders who are homeless, but not the proportion of homeless people who are sex offenders. This study seeks to address that research gap by comparing the population of homeless sex offenders in 41 states to the general homeless population to investigate the relevance of sex offenders as a subpopulation worthy of more consideration by scholars, advocates, and policymakers. The particular interventions that may be appropriate to or effective in addressing homelessness in this subpopulation are beyond the scope of this study, but some ideas for further research will be suggested.

Existing Subpopulations of Homelessness

Scholars and policymakers generally understand that the homeless population is not a monolith. HUD’s Annual Homelessness Assessment Report to the U.S. Congress divides the homeless population into broad subpopulations: individuals without families, families with children, unaccompanied youth, veterans, and the chronically homeless.12 The HUD Continuum of Care Homeless Populations and Subpopulations report includes further subcategorization based on age, race and ethnicity, gender identity, and characteristics of severe mental illness, substance abuse, HIV status, and exposure to domestic violence.13 Culhane (2019) explored the rapidly growing and uniquely challenging subpopulation of elderly homeless,14 Metraux and Culhane (2004) examined the interrelationship between the burgeoning U.S. prison population and the reemergence of homelessness in the early 2000s.15 The authors of the latter found that between 4.2 and 13.1 percent of offenders released from prison were housed in a shelter after release, a number which varied considerably based on the severity of the offense, though their study notably did not consider the specific category of sexual offenses. Still, the findings suggested that former criminal offenders may constitute a distinct subpopulation. Kushel et al. (2023) found that, two decades later, almost 80 percent of homeless individuals in California, who account for approximately half of the nation’s homeless population, had some form of criminal history that resulted in incarceration in jail or prison.16 That study also found that a combined two-thirds of homeless individuals used some type of hard narcotic, and more than 80 percent experienced some form of mental illness.17 These findings suggest that some of these characteristics may not constitute distinct subpopulations but rather represent nearly universal characteristics of the homeless population.

Despite Kushel et al.’s (2023) comprehensiveness, especially compared to the various HUD reports and smaller-scale studies, the authors still failed to identify sex offenders as a distinct subpopulation or even a category of interest.18 HUD does make a reference to sex offenders in the regulations for its homelessness programs, 24 CFR 578.93(b)(4), which provides programs with the discretion to exclude sex offenders if the program also includes children.19 However, homelessness scholars have almost entirely avoided the subject of sex offenders. Among policy organizations that work on both homelessness and criminal justice, the Urban Institute is one of the few that has produced reports that even mention this intersection, though even their research is from decades ago. Roman and Travis (2004) offered the most direct consideration of the subject in their study of prisoner reentry and homelessness, identifying social stigma, pressure on landlords, exclusionary criteria for shelters and housing programs, and legal residence restrictions as unique challenges for sex offenders leaving prison that may increase their likelihood of homelessness.20 The only other mentions of sex offenders and homelessness by the Urban Institute were far more limited. Theodos, Popkin, Guernsey, and Getsinger (2010) praised an innovative program for the “hard to house” but noted it excluded sex offenders.21 And Burt et al. (2010) made passing mention of exclusionary program eligibility criteria for people with criminal histories, including sex offenders. They recommended that those requirements be reduced, though the authors stopped short of calling for those changes specifically for sex offenders.22

Sex Offenders and Homelessness

The primary source of information on the intersection of sexual offending and homelessness is within criminological literature on the challenges that the population faces during re-entry, especially due to the litany of restrictions to which they are subjected upon release, which scholars suggest increase homelessness. Harris, Levenson, and Ackerman (2014) found that between two and five percent of the nation’s registered sex offenders are homeless, a finding reaffirmed by state-specific studies such as those of South Carolina (Cann and Scott 2020) and Delaware (Metraux and Modeas 2023).23,24,25 The potential reasons for such a high rate of homelessness among registered sex offenders are many, ranging from individual-level factors (e.g., cognitive functioning and childhood trauma) to community-level and social structural factors (e.g., public policy, housing affordability, and social stigmatization).

Individual-Level Causes of Sex Offender Homelessness

Research on individual-level factors influencing sex offender homelessness is relatively limited, though several studies hold homelessness as an implication of their findings. Lee, Tyler, and Wright (2010) do not explicitly mention sex offenders, but they theorize the ways in which at-risk populations become homeless due to a combination of personal vulnerabilities and experiences, which holds considerable relevance for sex offenders.26 Levenson, Willis, and Prescott (2016) found that male sex offenders were several times as likely to report high adverse childhood experiences (ACE) scores compared to the general male population.27 Liu et al.’s (2021) systematic review and meta-analysis found a high prevalence of high ACE scores among the homeless population, offering additional insight into Levenson, Willis, and Prescott’s (2016) findings.28 Similarly, findings from Joyal et al. (2013) and Stone, Dowling, and Cameron (2018) present a possible connection between the high prevalence of low cognitive functioning among sex offenders and an overrepresentation of low cognitive functioning among the homeless population.29–30 Although there are a few studies that approach the issue of individual-level factors that may drive sex offender homelessness, this area of research is critically underdeveloped.

Community-level Causes of Sex Offender Homelessness

Far more research has focused on the impact of various structural factors on sex offenders. Sex offenders are subjected to a wide variety of policies in different states, though these policies tend to fall into four categories: registration, community notification, residence restriction, and civil commitment.

Registration Policies

The first state to require sex offenders to register with law enforcement was California, which did so in 1947.31 The original intention of sex offender registries was to provide investigators with a ready-made list of possible suspects in the vicinity of a crime. However, their usefulness to the criminal justice system grew to include providing prosecutors with additional leverage in negotiating plea deals and allowing law enforcement to use charges for an offender’s failure to register or other violations as a stand-in for crimes they could not prove.32 By 1996, all states had created some form of sex offender registry.33 The U.S. Congress’s passage of the Adam Walsh Act in 2005 established a national registry to which all states were required to contribute, including offenses dating back to the 1970s.34 The Adam Walsh Act also required states to instruct law enforcement to inform the public when sex offenders were being released from prison through so-called “community notification” policies, though not every state is in full compliance with that law.35

Community Notification Policies

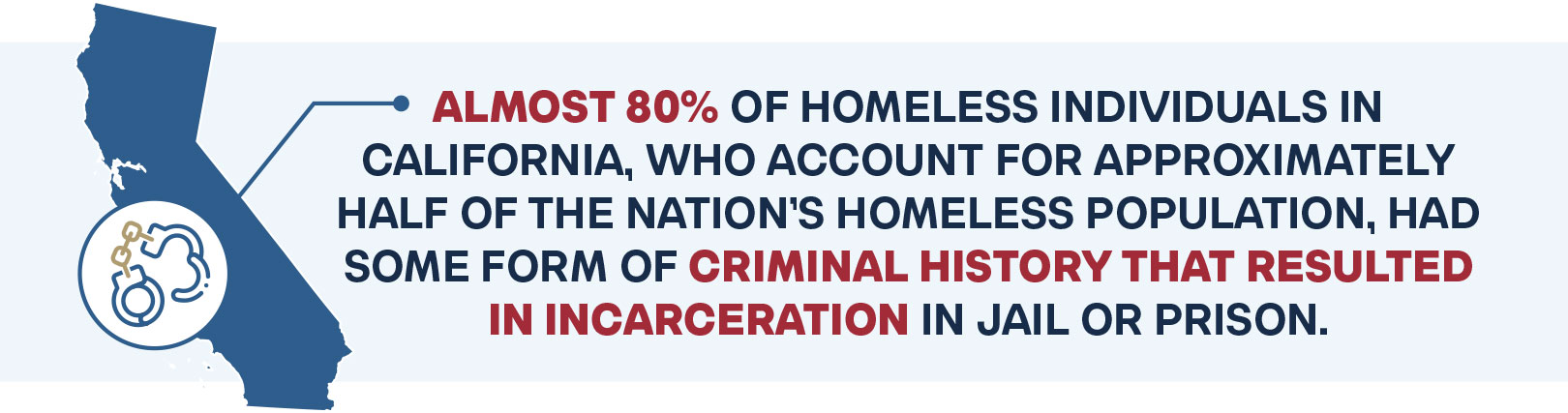

Community notification policies vary in content far more than registration policies, which are similar in purpose, though distinct in structure and governance, across states. Despite federal requirements of the Adam Walsh Act, fewer than half of the states have some form of community notification policy, and those that do differ considerably in the scope and implementation of their policies. On one end is California, which leaves notification policies up to local law enforcement agencies; on the other is Alabama, which requires law enforcement to distribute leaflets with identifying information about the released sex offender to everyone living within 1,000 feet of the offender’s residential address.36 Lasher and McGrath (2012) systematically reviewed the literature on policies related to sex offender community notification and their potential impact on employment and housing opportunities.37 A significant number of studies found an impact, though only the more active forms of community notification, such as those in Alabama, were associated with social destabilization related to employment or housing.38

Residence Restrictions

Sex offender residence restrictions, which legally prohibit sex offenders from living in certain areas commonly associated with children, under criminal penalty, are by far the most widely explored sex offender policy as it relates to homelessness. The work of J.S. Levenson has explored the ways these sex offender residence restrictions create collateral consequences for sex offenders far beyond their prison sentence or even the challenges associated with other felony offenses. Levenson and Cotter (2005) surveyed sex offenders about how they navigate the effects of a Florida law forbidding them from living within 1,000 feet of schools and daycares.39 The authors found that more than half of sex offenders found it more difficult to attain affordable housing, and just under half were unable to live with supportive family members because their residences fell within an exclusion zone.40 A similar survey in Indiana found that nearly two-thirds of sex offenders feared they might become homeless as a result of residence restrictions in that state.41 Sex offenders surveyed in a study by Mercado, Alvarez, and Levenson (2008) reported that they had to move more frequently because of residence restrictions, a finding affirmed by Rydberg et al.’s (2018) quasi-experimental study that found that sex offenders were twice as likely to move more than three times following release from prison after a statewide residence restriction went into effect.42–43 Frequent residence movement is strongly associated with homelessness.44

The two strongest studies that investigated the potential of residence restrictions to increase sex offender homelessness were Socia, Levenson, and Ackerman (2014) and Cann and Scott (2020).45–46 Socia, Levenson, and Ackerman (2014) conducted regression analyses of residence restrictions along with a number of other variables to test their relationships with the prevalence of homeless sex offenders in different counties in Florida.47 The results showed that a one-percent increase in geographic coverage by a residence restriction in a county led to a one-percent increase in the number of homeless sex offenders.48 Cann and Scott (2020) analyzed the change in the homeless rate of the South Carolina sex offender registry over more than a decade to examine the potential impact of that state’s sex offender residence restriction law.49 The authors found a significant increase in sex offender homelessness following the adoption of the law, but they could not isolate the impact from other potential explanations.50

Civil Commitment

The U.S. is unique in its policy of civilly committing some sex offenders to psychiatric institutions under distinct procedures from all other types of psychiatric commitment. This practice began in the early twentieth century as part of a movement to classify sex offenders, especially those who committed crimes against children, as “sexual psychopaths.”51 It was relatively unusual for child molesters to receive prison sentences until after the mid-twentieth century.52 Before then, child molesters most often received probation sentences, and some were committed to psychiatric institutions in connection with their offending patterns. The latter half of the twentieth century brought a dramatic shift in policy towards sex offenders, with increased reliance on long prison sentences and, for a few decades, little attention to obsolete or repealed sexual psychopath laws.53

Renewed interest in the civil commitment of sex offenders came towards the end of the twentieth century, with states adopting a new paradigm called “sexually violent predator” laws.54 These laws allow states to designate certain sex offenders as sexually violent predators, which became a special classification within the sex offender registry that has heightened community notification requirements and permits prosecutors to petition courts to civilly commit such offenders to psychiatric institutions under a lower standard than applies to the general population.55 Instead of requiring individuals to exhibit signs of severe mental illness and present an immediate danger to themselves or others as evaluated by a psychologist, sexually violent predators need only be shown to have a “mental abnormality,” a vague standard that falls outside of the Diagnostics and Statistical Manual (DSM) and essentially allows for broad confinement of offenders who would otherwise not meet commitment criteria.56 Because the presence of a mental condition justifies civil commitment, sexually violent predator laws have a pretext of treatment. Miller (2010) points out that treatment is fairly limited in these facilities, and committees have strong disincentives to participate in treatment or discuss their crimes or underlying sexual deviance.57 The result is that those committed tend to stay in psychiatric facilities for periods that may exceed their original prison sentence.58

Importantly, civil commitment of sexually violent predators need not happen in lieu of prison. Rather, prosecutors can petition for commitment upon release from prison or even after the individual is back in the community. These laws have been the subject of significant litigation, but ultimately, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Kansas v. Hendricks (1997) that they did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment’s protections of due process or against double jeopardy.59 By 2006, more than 4,500 individuals were committed under sexually violent predator laws nationwide.60

While sexually violent predator statutes may seem less directly relevant to homelessness, it is worth considering that sex offenders who exhibit the highest degrees of mental and social dysfunction and whose crimes would be the most severely stigmatized in the community (such as those who might be classified as sexually violent predators) could be at particularly high risk of homelessness. But if those individuals are committed to psychiatric facilities indefinitely, then they are not homeless. Thus, it is possible that sexually violent predator statutes, unlike the other sex offender policies, could reduce sex offender homelessness through indefinite incapacitation. However, for those sex offenders who are eventually released from psychiatric institutions, homelessness is a very high risk.61

Existing literature on sex offenders describes many relevant individual-level and community-level risk factors for homelessness. However, it has failed as of yet to establish sex offenders as a legitimate subpopulation of homelessness worthy of attention from researchers and policymakers. Although research has established that sex offenders have higher rates of homelessness than the general public, it is not yet clear what proportion of the general homeless population is on the sex offender registry, and it is that question that this study aims to answer. This study has considerable relevance to policy because of the complexities of this population, both in terms of risk profile and the policies to which they are subjected. This study raises further questions about how those complexities may hinder the effectiveness of certain homelessness interventions but will require further research to answer.

Methodology

This study will use the basic statistical functions of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software to analyze the prevalence of sex offenders within the homeless populations of 41 states. Although there is a national sex offender registry overseen by the Sex Offender Sentencing, Monitoring, Apprehending, Registering, and Tracking (SMART) Office of the U.S. Department of Justice, that database is comprised of submissions from 50 separate sex offender registries across the country. Each state registry is separately developed and managed, leading to variability in the quality and labeling of data. While each state maintains a registry and reports data to the national registry, most states are out of compliance with the Adam Walsh Act to some degree, contributing further to the variability in structure and access among states.62 Of 50 states, nine were removed from this study’s sample for various reasons, including refusal of access (Minnesota), inability to provide homeless-specific data (Nevada, New York, Maine, Michigan, West Virginia), or no response (Mississippi, Oregon, South Carolina).

State-level datasets were collected in a variety of formats, including Excel sheets with all the state’s sex offenders, databases scraped using the DataMiner plugin, and aggregate counts with no additional context sent by registry managers in response to Freedom of Information Act requests. Each dataset was cleaned to eliminate duplicate entries, offenders who lived out of state, were in prison, deported, institutionalized, or had a verified address. The remaining sex offenders were divided into two categories: those labeled as homeless or a related term, or who had an address that described a state of homelessness (e.g., under a bridge or living in a tent), and those with no address or listed as “whereabouts unknown.” Importantly, sex offenders who listed their address as a homeless shelter or transitional housing provider are not labeled as homeless in registries, even though they would be considered homeless by HUD’s definition of homelessness for the Point-in-Time (PIT) Count.63 The decision not to include sex offenders who are not labeled as “homeless” or “address unknown” but may, in fact, be homeless as defined by HUD was necessary due to the difficulty in matching addresses and the large number of states in which no such data collection would even be possible given the structure and availability of the registry. This decision does, however, imply that this study undercounts HUD-defined homelessness on the registry, though evidence that sex offenders are excluded from most homeless shelters suggests that the underestimation may be relatively marginal.

The decision to keep the data explicitly labeled as “homeless” separate from the data labeled “no address” was informed by prior literature on the sex offender registry that attests to the ambiguity of the latter category. The primary limitation of the “no address” dataset is that it is unclear whether the individuals in this category are homeless or if they simply did not provide the required information that would allow them to be categorized otherwise.64 While it may seem intuitive to include offenders who are missing or who have absconded in this category, offenders who are out of compliance are listed separately within each registry. Cann and Scott (2020) make note of this problem and ultimately decided not to include sex offenders with no address in their sample, with the acknowledgment that this would likely mean their research undercounts homelessness and thus provides only a conservative estimate.65 The present study addresses this issue by conducting two comparisons: one between sex offenders labeled as homeless and general homeless data and the other between a combined dataset of sex offenders labeled as “homeless” and those labeled “no address,” which, in effect, creates an upper and lower bound of the proportion of the homeless population who are sex offenders.

The final major decision about the data was which general homelessness dataset to use for the comparison. HUD’s annual census, the Point-in-Time Count, provides the homeless population for each state. Even acknowledging the limitations of the Point-in-Time Counts’ rudimentary data collection methods, they remain the most consistent data on homelessness—and the most widely used. The Point-in-Time Count data is divided into two major categories: unsheltered and sheltered homeless.i State sex offender registries, however, do not specify the type of homelessness as defined by HUD. Moreover, both the sex offender registry and HUD’s Point-in-Time Count classify homelessness as binary and not a spectrum for the purposes of data collection, which in turn ignores potentially relevant but fluid categories of housing insecurity, a severe limitation raised by Socia, Levenson, and Ackerman (2014).66 While all of these categories can certainly be problematized, a few insights from other scholars informed how this study decided which categories of homelessness it deemed relevant. First, Rolfe, Tewksbury, and Schroeder (2017) investigated homeless shelters in Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, and Tennessee. They found that 71 percent of homeless shelters in those states had policies to refuse admission of sex offenders, with a nearly equal number conducting sex offender registry checks upon entrance.67 Stucky and Ottensmann (2014) excluded from their research a group of sex offenders who had listed homeless shelters as their address and were thus not labeled as homeless, which suggests that sex offenders explicitly listed as “homeless” or “transient” are likely best categorized as unsheltered homeless.68 While these two studies suggest that unsheltered homelessness is the most appropriate categorization because of the relative ambiguity, this study compares the homeless sex offender population to both the unsheltered homeless and total homeless (combined sheltered and unsheltered) populations.

For each of the 41 states examined in this paper, four proportions will be created: (1) the number of registered sex offenders listed as homeless compared to the unsheltered homeless population; (2) the number of registered sex offenders listed as “homeless” or “address unknown” compared to the unsheltered homeless population; (3) the number of registered sex offenders listed as “homeless” compared to the total homeless population; (4) the number of registered sex offenders listed as “homeless” or “address unknown” compared to the total homeless population.

i A related issue that is not as pressing for the purposes of this study is that sex offenders who were homeless but have been provided with permanent supportive housing through a HUD homelessness program are not considered homeless by HUD or by the sex offender registry. Therefore, they would not be included in this sample, though it could be an area for future research to see how successful such programs are at moving sex offenders off the street at scale.

Results

Across the 41 state sex offender registries examined, a total of 21,583 individual sex offenders were identified as homeless, and another 8,796 sex offenders were classified as “address unknown.” These figures were analyzed primarily in comparison to the unsheltered and total homeless population at the state level, but an average figure using the combined sample and the combined unsheltered and total homeless populations is also included in Figure 1.

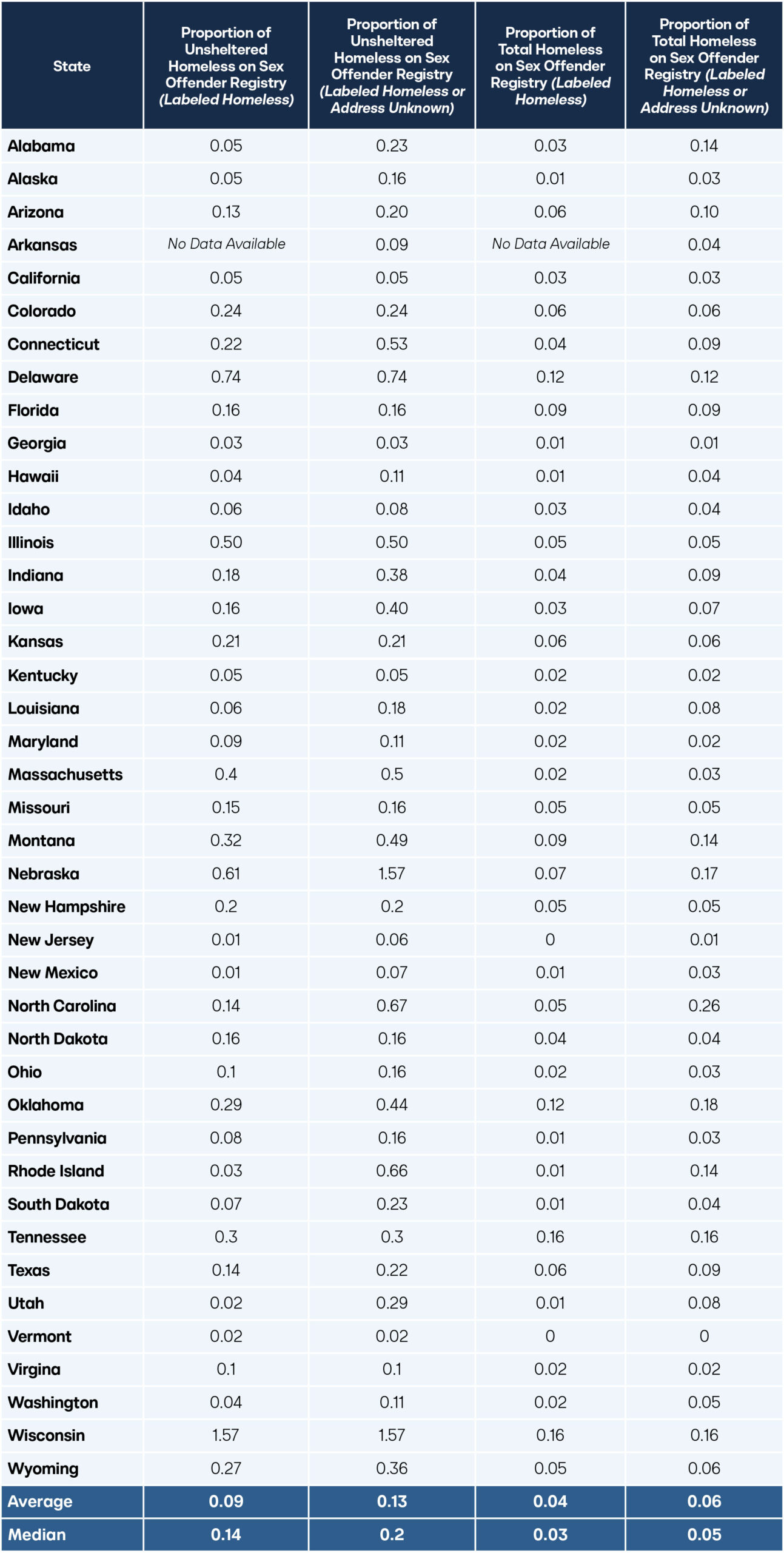

Each of the four measures comparing registered sex offenders and homelessness among the 41 states analyzed has wide variability. Figure 1 shows the results for all states in the sample (N = 41) across all four measures, and then the results for each measure are reported in more detail individually. Results were categorized as small (0.00-0.10), medium (0.10-0.20), large (0.200.50), and exceptionally large (0.50).

Figure 1: Results of Registered Sex Offenders and Homeless Point-in-Time Count Comparison by State

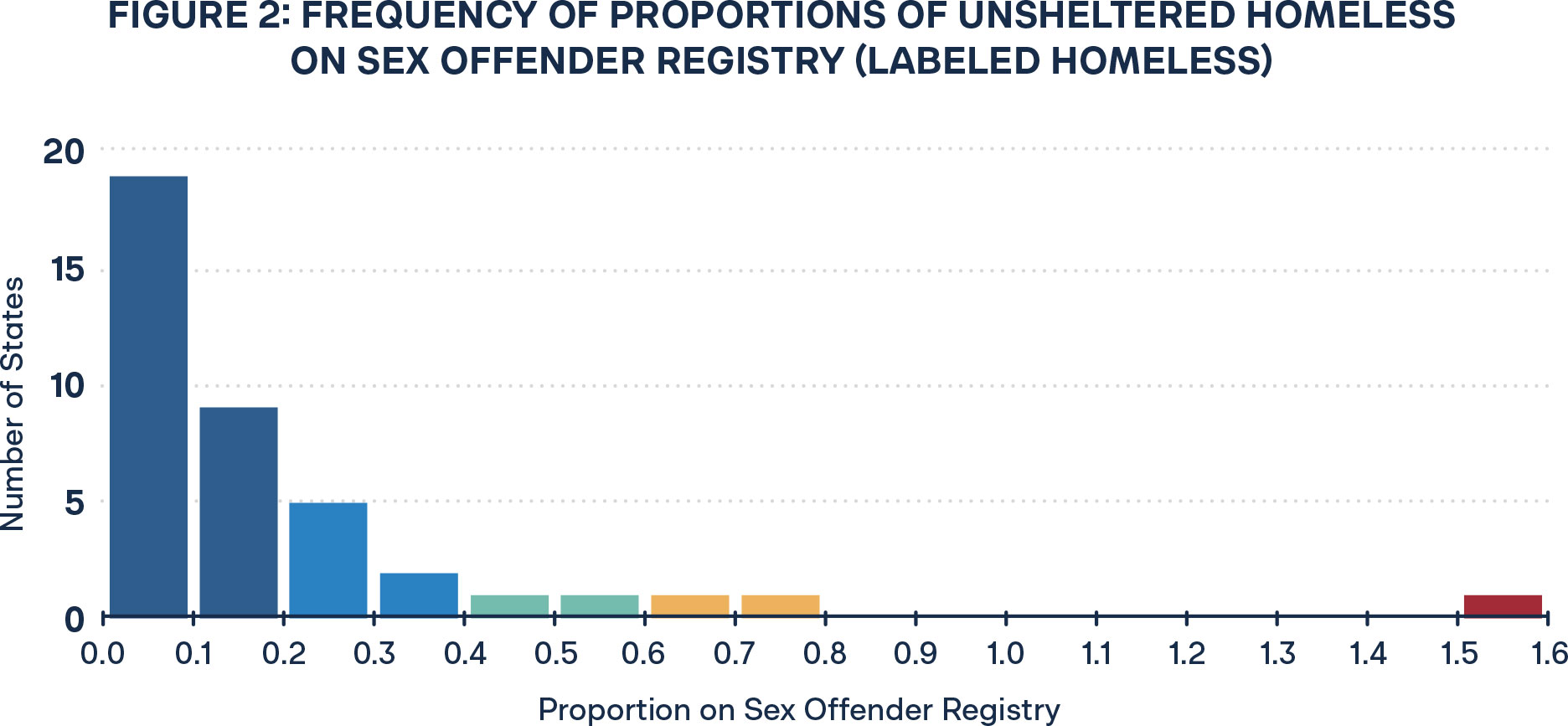

The number of states with similar proportions of unsheltered homeless populations on the sex offender registry listed as homeless is reported in Figure 2. The proportions ranged from 0.1 in New Jersey and New Mexico to 0.74 in Delaware, with the true maximum value of 1.57 in Wisconsin noted as an exceptional outlier.ii Arkansas was not included in this portion of the analysis because its registry could only provide sex offenders whose addresses were unknown and not explicitly labeled homeless. Nearly half of the sample (N = 19) had proportions between 0.01 and 0.10, indicating a small subpopulation of sex offenders within the unsheltered homeless population. Nine states’ proportions fell between 0.10 and 0.20, indicating a medium-sized subpopulation. Eight states had proportions between 0.20 and 0.5, indicating a large subpopulation, while one-fifth (N = 4) had proportions above 0.50, indicating an exceptionally large subpopulation of sex offenders within the unsheltered homeless population. The four states with proportions above 0.50 were Illinois (0.50), Nebraska (0.61), Delaware (0.74), and Wisconsin (1.57). The average result across the whole sample, weighted for population, was 0.09.

iiWisconsin’s 1.57 value implies that there are more registered sex offenders listed as homeless than there are unsheltered homeless people in the state. A few possible explanations are that the Point-in-Time Count used to measure unsheltered homelessness undercounts the actual value, which is consistent with the literature on the Point-in-Time Count (Shinn, Yu, Zoltowski, and Wu 2024). Another possibility is that some unknown proportion of Wisconsin’s registered sex offenders listed as homeless are sheltered, though there were several entries in the registry not labeled as homeless that listed shelters as their address, so it is unclear the extent to which this is the primary issue with Wisconsin’s data.

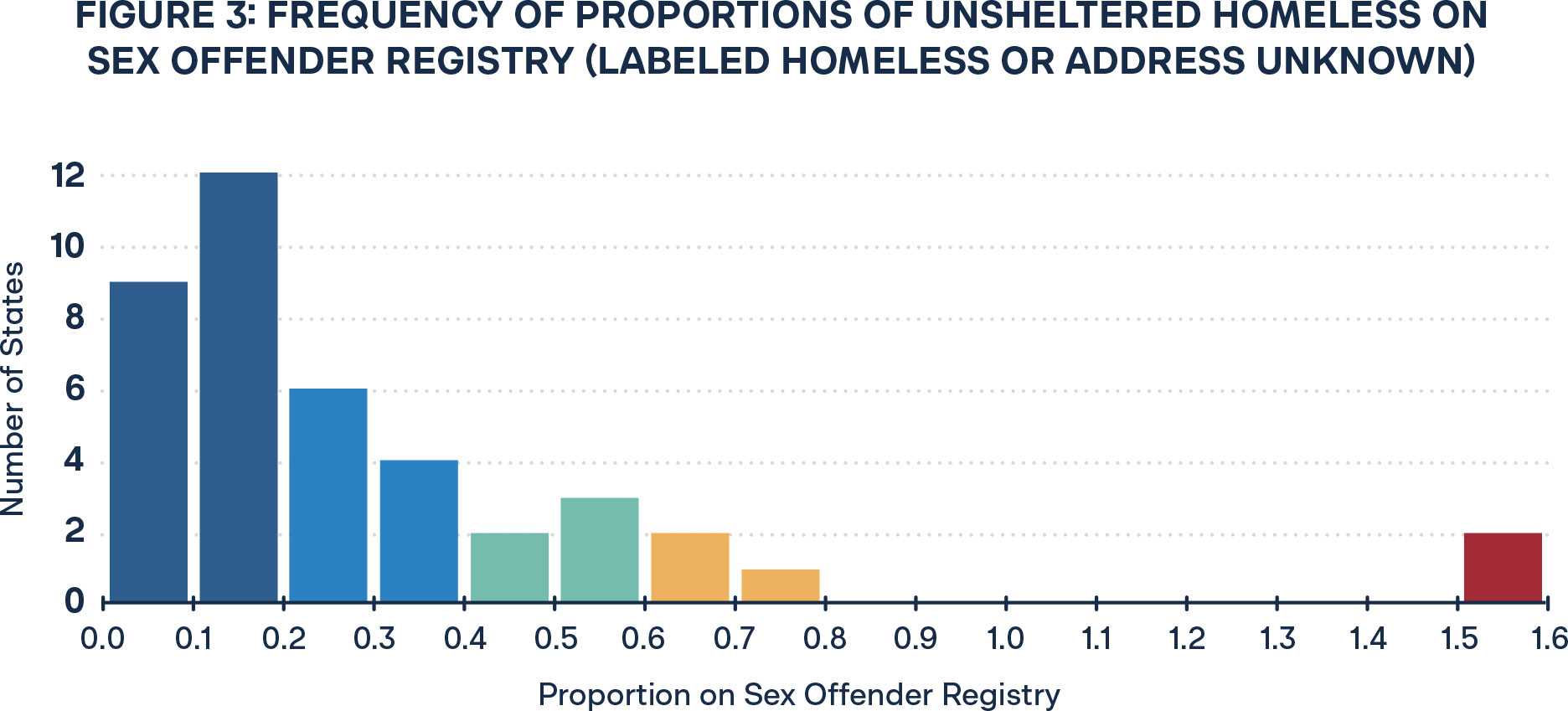

The number of states with similar proportions of unsheltered homeless on each state’s sex offender registry listed as “homeless” or “address unknown” is reported in Figure 3. The proportions ranged from 0.2 in Vermont to 0.74 in Delaware, with outliers in Nebraska and Wisconsin, both at 1.57. Nebraska’s and Wisconsin’s outlier results exceeded the total unsheltered homeless populations of those states, which again possibly indicates an undercount of unsheltered homeless people or a misclassification of some number of homeless sex offenders as unsheltered.69 Arkansas was included in this portion of the analysis due to the broadened category that includes both sex offenders labeled as “homeless” and those labeled as “address unknown.” Just under a quarter of the sample (N = 9) had proportions between 0.01 and 0.1, indicating a small subpopulation of sex offenders within the unsheltered homeless population. Compared to the results in Figure 2, a much larger number of states fell into the medium and large subpopulation groupings with the broadened criteria for what is considered homeless. More than a quarter of the sample (N = 12) fell into each of the medium (0.10-0.20) and large (0.20-0.50) subpopulation categories, and nearly one-fifth of the sample (N = 8) exceeded 0.50. The eight states with registered sex offenders labeled as “homeless” or “address unknown” making up more than half of their unsheltered homeless population were: Connecticut (0.53), Delaware (0.74), Illinois (0.50), Massachusetts (0.50), North Carolina (0.67), Nebraska (1.57) Rhode Island (0.66), and Wisconsin (1.57). The average size of the subpopulation across the whole sample was 0.13.

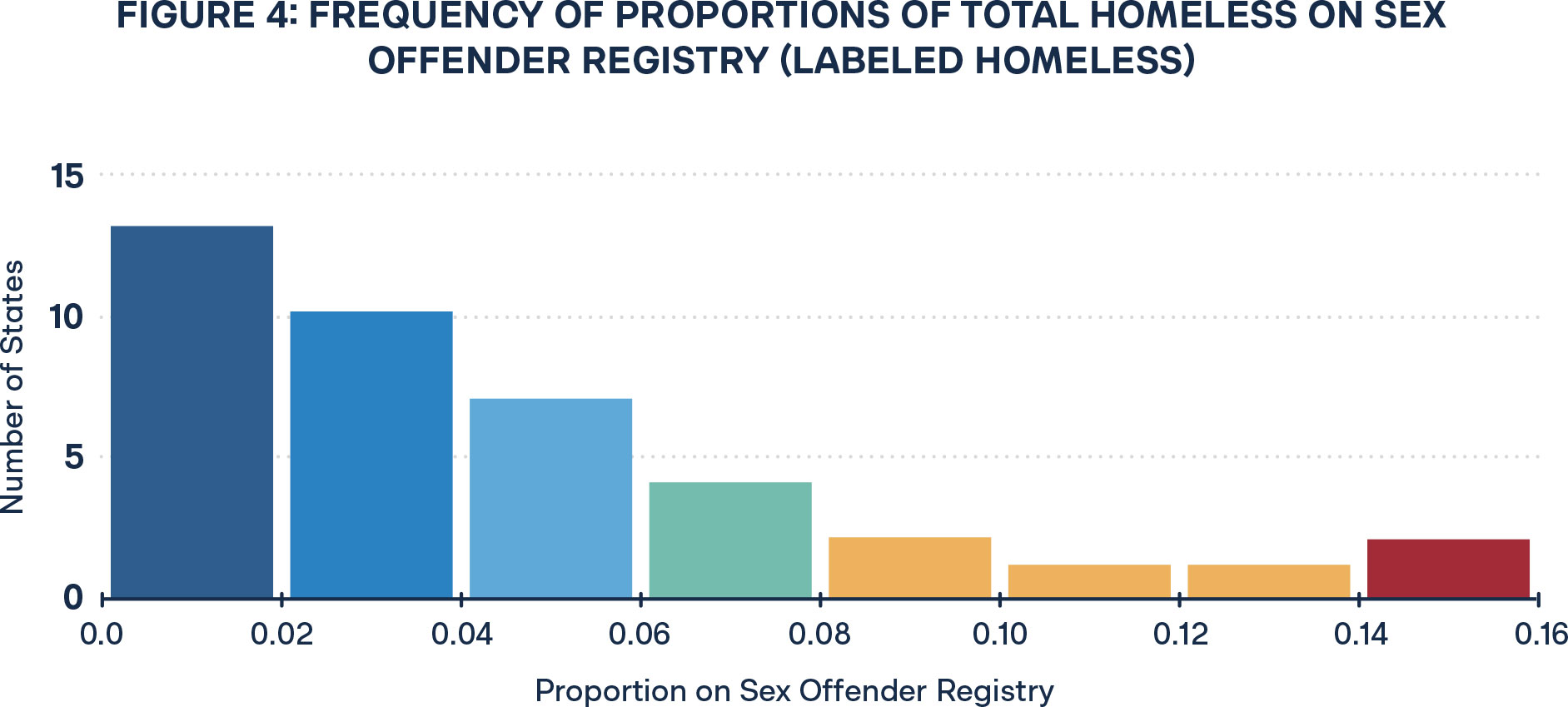

The number of states with similar proportions of total homeless on each state sex offender registry listed as homeless is reported in Figure 4. The proportions ranged from 0.00 in New Jersey and Vermont to 0.16 in Tennessee and Wisconsin. Nebraska’s and Wisconsin’s outlier results of the comparisons that were limited to unsheltered homelessness appeared much closer to the results from other states when compared to total homelessness but were both still in the fourth quartile of results. Arkansas was again not included in this portion of the analysis because its registry could only provide sex offenders whose addresses were unknown and not explicitly labeled “homeless.” Almost one-third of the sample (N = 13) had proportions between 0.00 and 0.02, and more than half (N = 23) were between 0.02 and 0.10. Only four states in the sample had proportions of their total homeless population on the sex offender registry in excess of 0.10: Delaware (0.12), Oklahoma (0.12), Tennessee (0.16), and Wisconsin (0.16). The average result across the sample was 0.04.

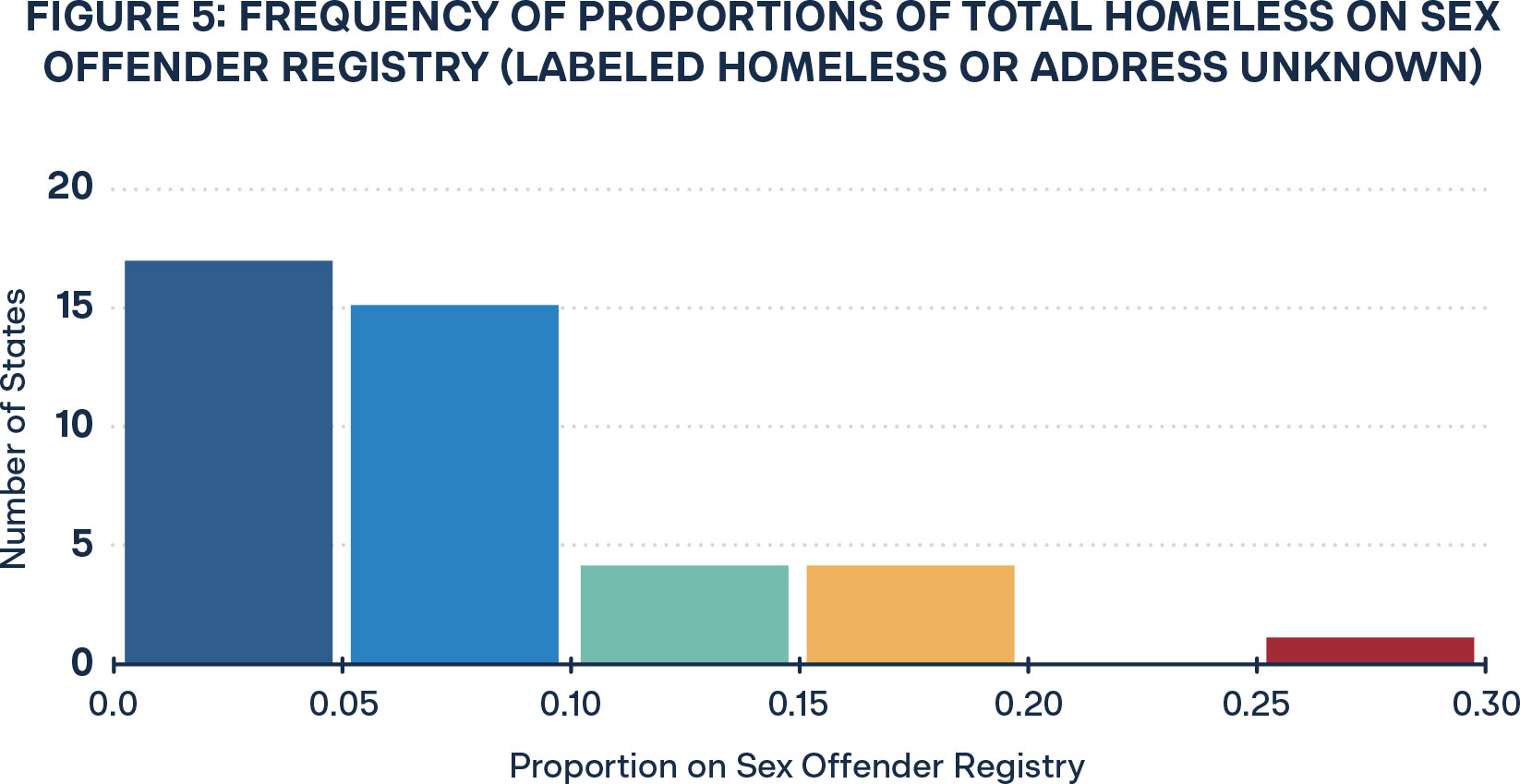

The number of states with similar proportions of total homeless populations on each state’s sex offender registry listed as “homeless” or “address unknown” is reported in Figure 5. The proportions ranged from 0.00 in Vermont to 0.26 in North Carolina. Even when the criteria for inclusion were broadened to include sex offenders labeled “address unknown” in addition to those labeled as “homeless,” only four states changed to a proportion above 0.10. Just over three-quarters of the sample (N = 32) was between 0.00 and 0.10, and an equal portion (N = 4) was between 0.10 and 0.15 as was between 0.15 and 0.20. The nine states above 0.10 were Alabama (0.14), Delaware (0.12), Montana (0.14), North Carolina (0.26), Nebraska (0.17), Oklahoma (0.18), Rhode Island (0.14), Tennessee (0.16), and Wisconsin (0.16). The average result across the sample was 0.06.

Analysis & Implications

Sex offenders appear to be a relevant and sizeable subpopulation of the homeless population in many states. When focusing specifically on the unsheltered population, which the literature and structure of the sex offender registries suggest is the most appropriate label for those listed as “homeless” or “address unknown” in the registry, the size of the subpopulation is alarming. There appears to be wider variability in the size of the subpopulation when limited to unsheltered homelessness (with far more states exceeding 0.10 and even 0.20) than when compared with the total homeless population. As a proportion of total homelessness, the majority of states fall below 0.10. These findings have implications for several areas of homelessness research and policy, including geographic variation in homelessness, comparisons to existing subpopulations in the factors that cause homelessness, homelessness interventions and services, and public safety.

Geographic Variation

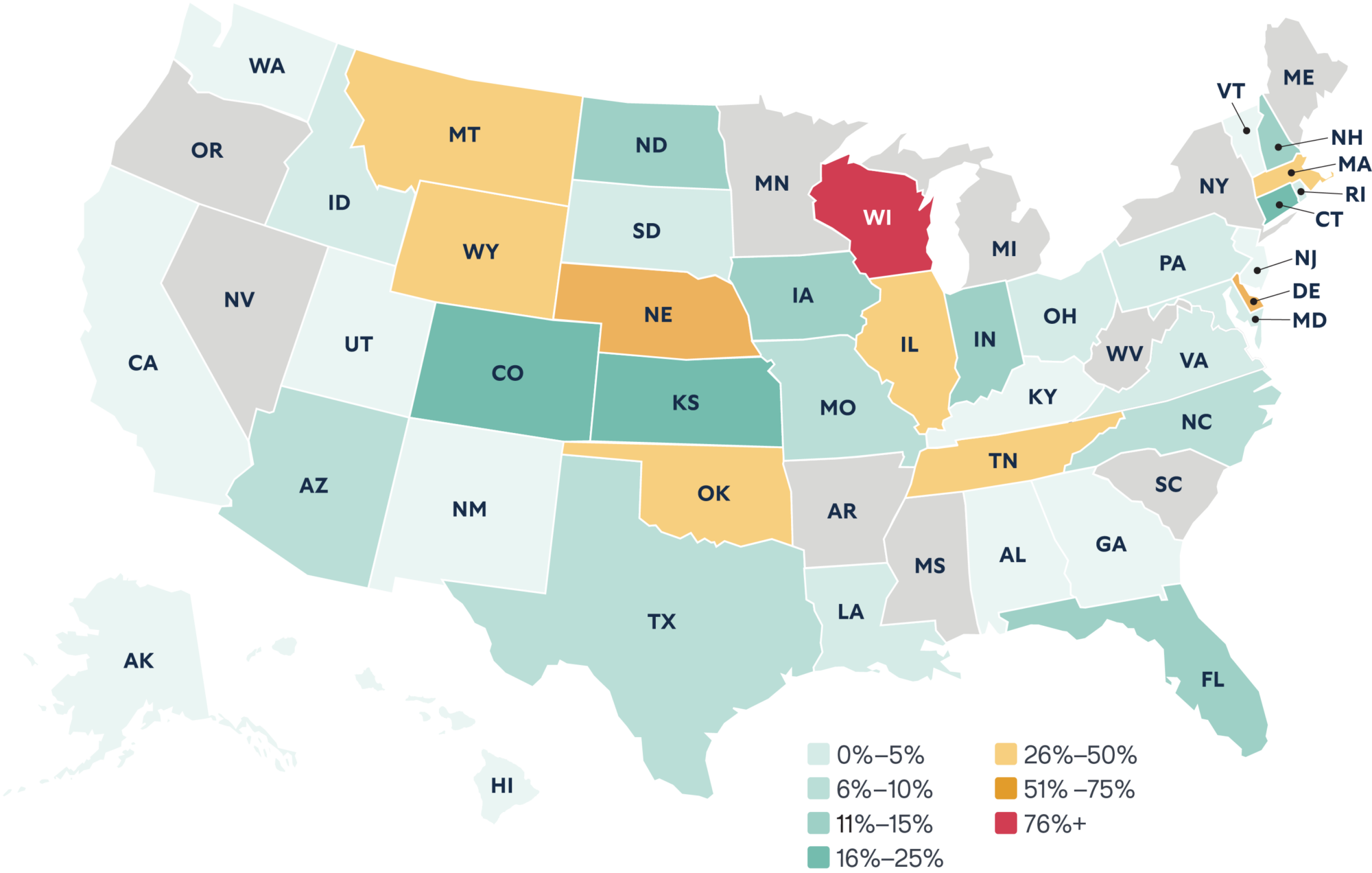

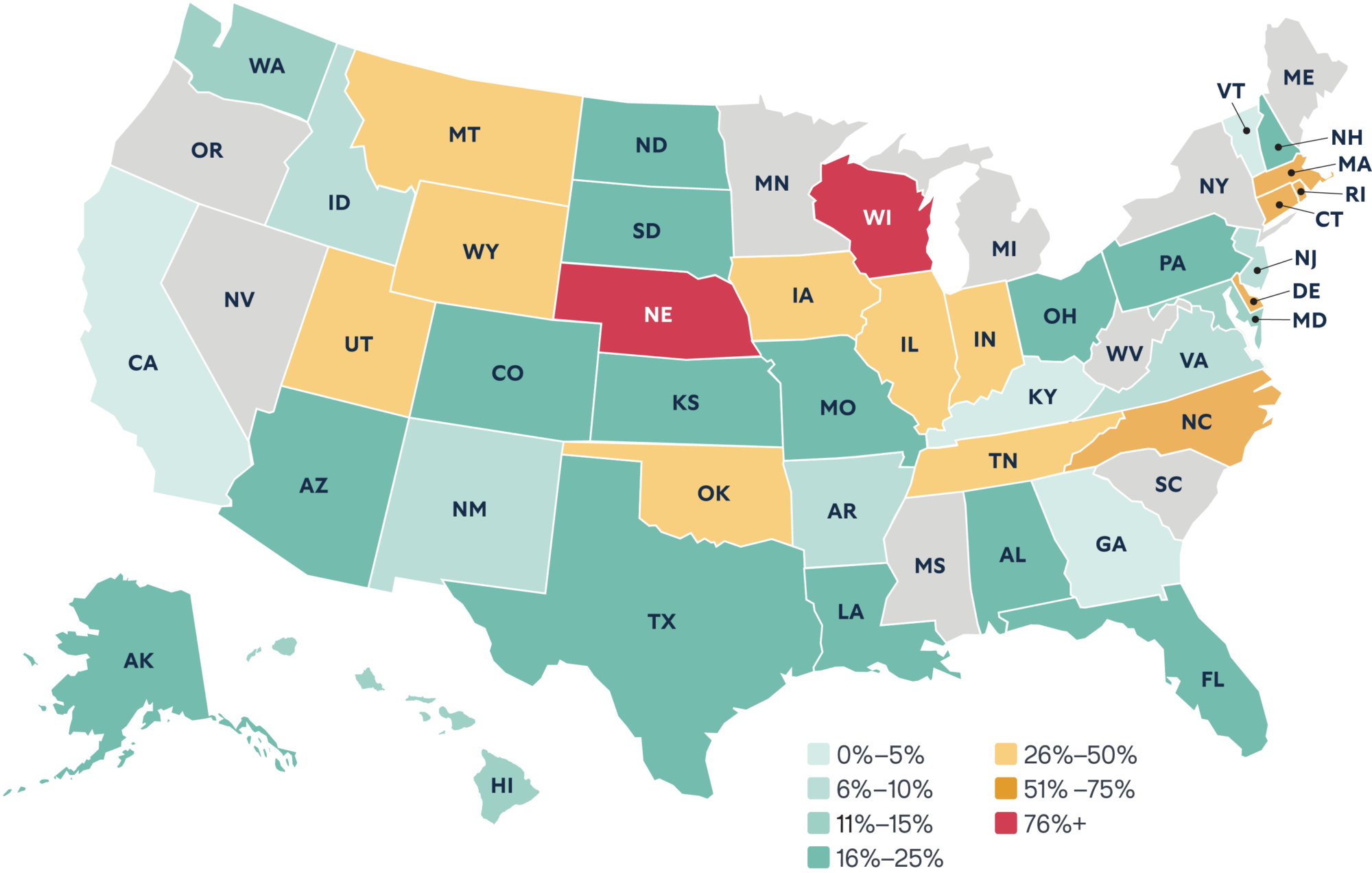

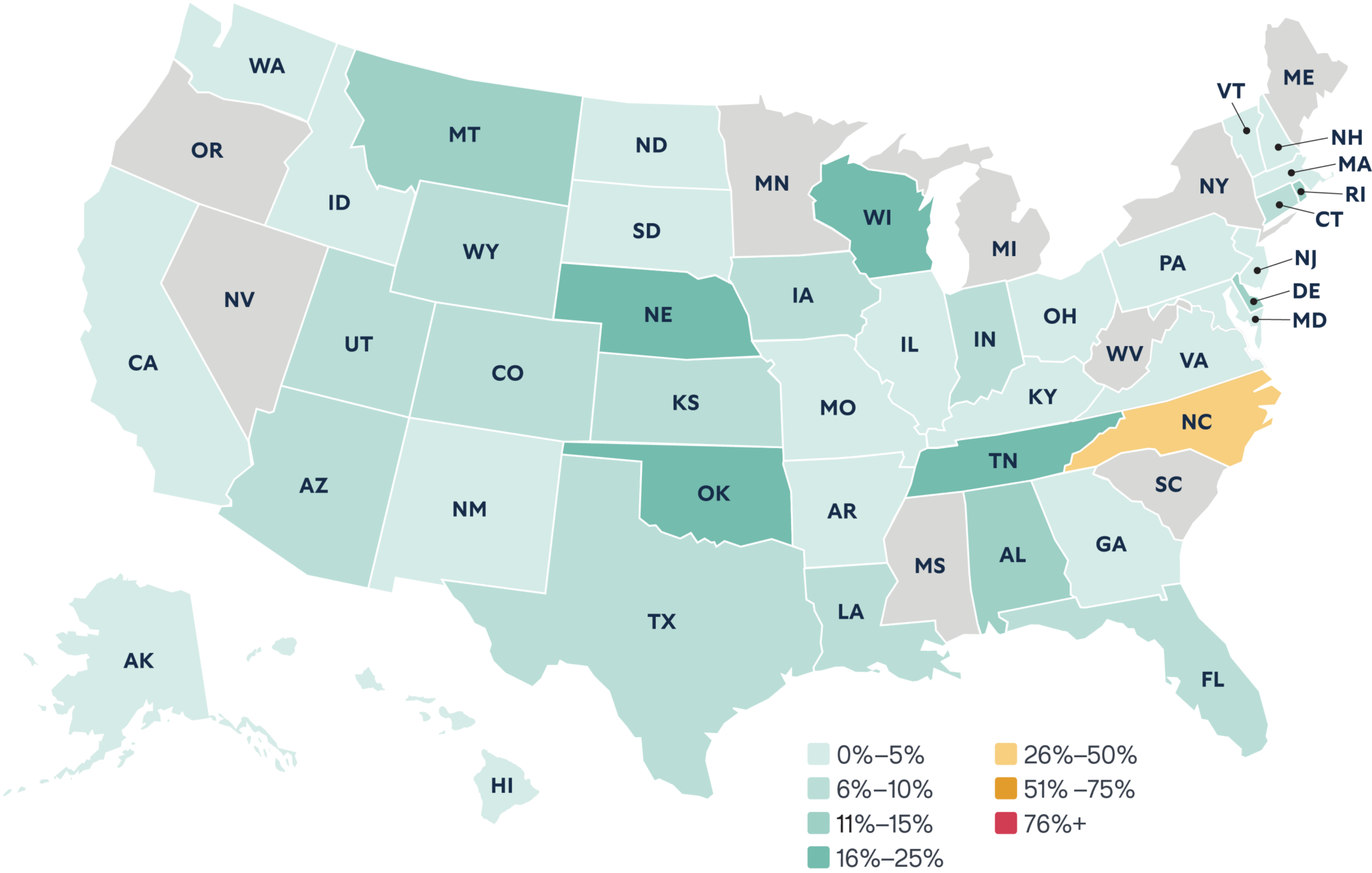

Given that the sample is based on state-level jurisdictions, the results of each of the four analyses are presented below in national maps (Figures 6-9). These figures offer a cursory view of potential geographic variations that could be further explored in future studies to determine potential causes of the significant variation in the results among states.

Figure 6: Map of States by Proportion of Unsheltered Homeless Population on Sex Offender Registry (Labeled Homeless)

Figure 7: Map of States by Proportion of Unsheltered Homeless Population on Sex Offender Registry (Labeled “Homeless” or “Address Unknown”)

Figure 8: Map of States by Proportion of Total Homeless Population on Sex Offender Registry (Labeled “Homeless”)

Figure 9: Map of States by Proportion of Total Homeless Population on Sex Offender Registry (Labeled “Homeless” or “Address Unknown”)

The precise geographic patterns are hard to discern due to the missing nine states from the sample. Figures 6 and 7 indicate possible geographic patterns of higher proportions of unsheltered homeless on the sex offender registry in the Midwest, the northern portion of the Mountain West, and southern New England. However, those geographic patterns do not hold strongly when compared to the total homeless population in Figures 8 and 9. The Southeast appears to have a potential cluster of higher proportions of total homeless on the sex offender registry in Figure 9, though the absence of data from South Carolina and Mississippi significantly limits the geographic analysis.

Subpopulations

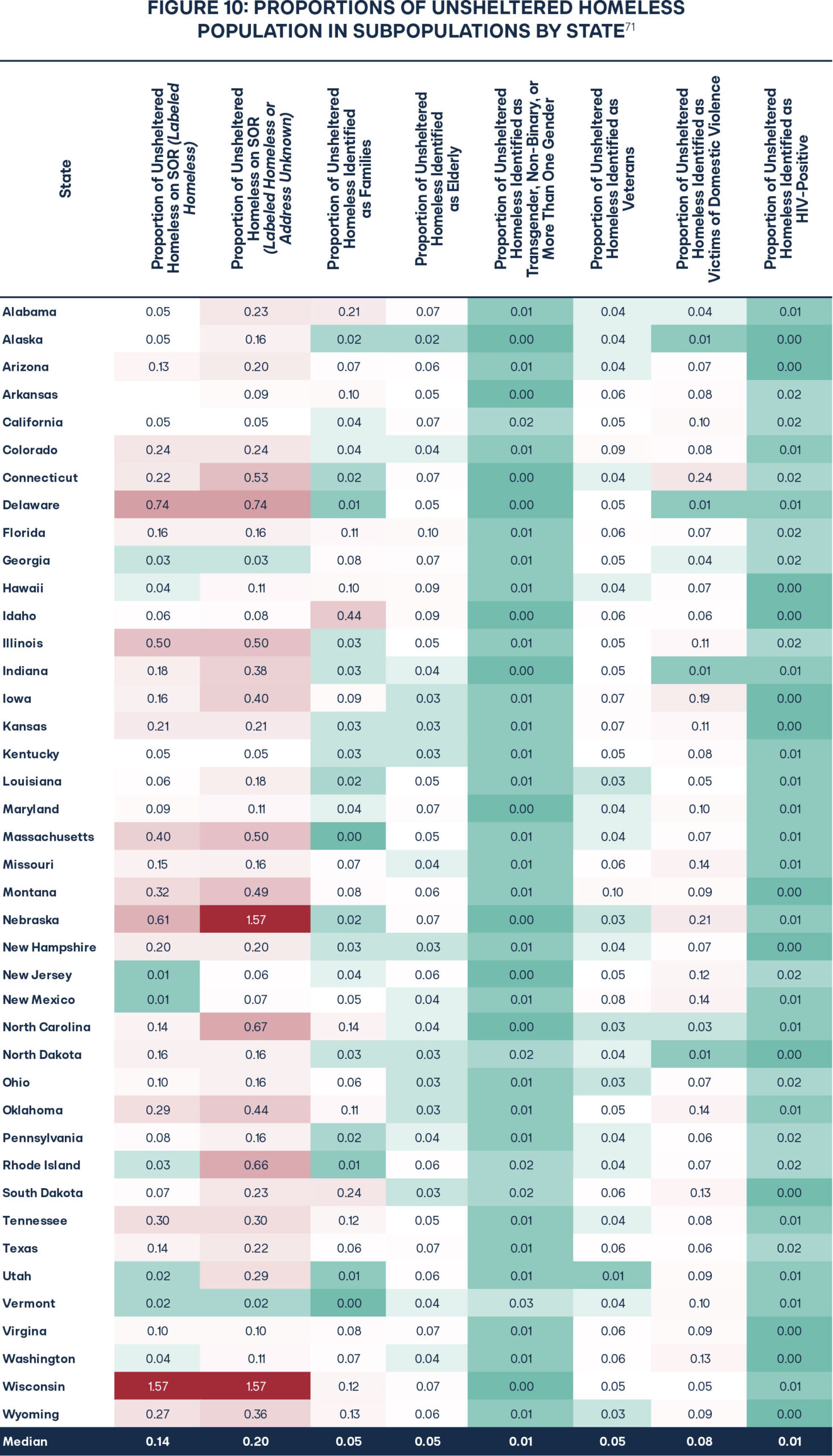

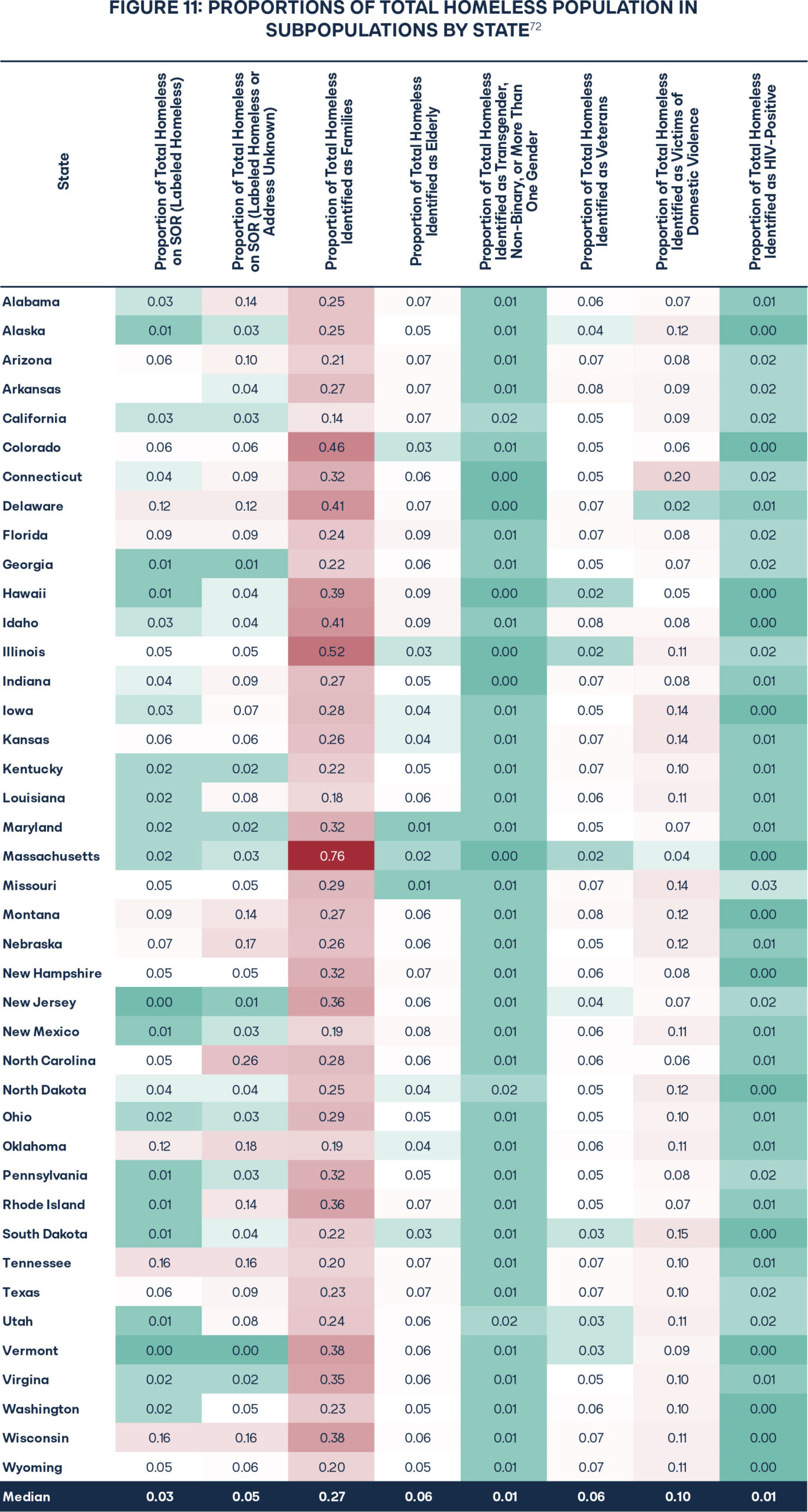

HUD tracks several different subpopulations of homeless individuals across race, gender, family status, veteran affiliation, exposure to domestic violence, behavioral health, and HIV status.70 HUD reports state and national statistics of how many homeless people fall into these categories based on the Point-in-Time Count, providing an opportunity to contextualize the size of the homeless sex offender subpopulation with HUD-tracked subpopulations. Most of the subpopulations for race and gender, with the notable exceptions of those identifying as Native American, Asian, Middle Eastern, Native Hawaiian, or as some variant of genderqueer, were far larger than the sex offender subpopulation as well as most other subpopulations unrelated to race and gender and are therefore not included in the comparison in Figures 10 and 11. Figure 10 compares the two measures of the sex offender subpopulation within unsheltered homelessness with the following HUD-tracked unsheltered subpopulations: families, veterans, transgender, non-binary or more than one gender, victims of domestic violence, HIV-positive, and elderly (over 64). Figure 11 compares the two measures of the sex offender subpopulation within the total homeless population with those same HUD-track subpopulations of the total homeless population.

Comparisons of the median proportions of each subpopulation of the unsheltered homeless population show that sex offenders are far larger than any of the selected HUD-tracked subpopulations. Notably, this pattern held for both sex offenders explicitly labeled as “homeless” (median = 0.14) and the measure that included sex offenders labeled as either “homeless” or “address unknown” (median = 0.20). The smallest subpopulations included in the comparison were unsheltered homeless people identified as having HIV/AIDS (median = 0.01) and as non-binary, transgender, or more than one gender (median = 0.01). Victims of domestic violence were the largest unsheltered subpopulation across states of those tracked by HUD (median = 0.08), and families, elderly, and veterans (medians = 0.05) were each only a fraction of the size of the sex offender subpopulation measures. These comparisons confirm that sex offenders are a significant subpopulation of unsheltered homelessness and warrant greater attention from HUD and researchers.

The sizes of the two measures of the sex offender subpopulation relative to several HUD-tracked subpopulations were much smaller when compared with the total homeless population. Only the proportions of homeless people identified as having HIV/AIDS (median = 0.01) and as non-binary, transgender, or more than one gender (median = 0.01) were smaller than the proportions of sex offenders labeled as “homeless” (median = 0.03) and labeled as “homeless” or “address unknown” (median = 0.05). Veterans and elderly homeless subpopulations (medians = 0.06) were comparably sized to the largest estimate of sex offenders but double the size of the smaller estimate. Families (median = 0.27) and victims of domestic violence (median = 0.10) made up far larger proportions of the total homeless population than either measure of sex offenders. Even though sex offenders seem to be one of the smaller subpopulations of total homelessness, the fact that they are still larger than several HUD-tracked subpopulations further affirms their relevance as a subpopulation.

Causes of Homelessness

The prevalence of registered sex offenders in the homeless population suggests additional complexity in our understanding of the drivers of homelessness. Sex offender residence restrictions and community notification policies have not been considered as part of the mainstream discourse on drivers of homelessness. Still, these findings suggest that they may be relevant. The impact of sex offender policies on homelessness, however, is not as easily theorized as it may seem. While many studies have suggested a connection between residence restrictions and homelessness, some studies offer evidence that the connection may be weaker than previously thought. Huebner et al. (2014) found no impact of the laws restricting where a sex offender resides on where sex offenders actually lived in Michigan and Missouri.73 Berenson and Appelbaum’s (2011) geospatial study found that while more than three-quarters of residences were prohibited by residence restrictions in two counties in New York, nearly all sex offenders simply lived in restricted locations.74 Gruebsic, Murray, and Mack (2008) contradicted another leading theory that argued that areas outside of sex offender restriction zones are less affordable or accessible and thus further disadvantage sex offenders at risk of homelessness.75 The prevalence of homeless sex offenders, combined with the conflicting evidence about the extent to which sex offender policies may be a major driver of homelessness, warrants more research by a broader array of scholars than just criminologists.

It is worth noting, however, that even if strong evidence emerges that sex offender policies drive homelessness, Rydberg, Dum, and Socia (2018) found that support for such policies remains very high within the public, regardless of the strength of evidence suggesting their ineffectiveness or harmful effects.76 As Federman (2021) notes, it is the public, not criminologists, who rightfully decide the direction of public policy in our system of government.77

Interventions and Services

As Theodos, Popkin, Guernsey, and Getsinger (2010) and Burt et al. (2010) note in their analyses of homelessness interventions, sex offenders are often excluded from traditional services, shelters, and housing.78–79 The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, however, gives programs broad discretion in whether to include sex offenders in their homelessness programs.80 It is important that programs take care to ensure that their participants are adequately protected from potential criminal activity and violence. It is also imperative that programs attract homeless individuals by making them comfortable, even if that is at the expense of sex offenders. Thus, eligibility requirements for many programs probably should not change even if risk is not a foremost consideration—client comfort alone is enough reason to keep sex offenders excluded. However, excluding sex offenders from existing programs warrants the creation of tailored homelessness programs for sex offenders, which is politically unpopular. This would likely have to be done through the criminal justice system, even at the risk of additional stigmatization, to ensure adequate oversight and specialization among staff. Similarly, because sex offenders are excluded from so many shelters, it is critical that outreach workers are made aware of their high prevalence on the street and adjust their practices and offers for services accordingly.

It is possible that the findings of Rolfe, Tewksbury, and Schroeder (2017) and others that a high proportion of homeless shelters exclude homeless people as a matter of policy are only part of the issue.81 Facilities’ geographic locations could also fall within residence restriction zones, categorically excluding sex offenders, even if the program or shelter intends to permit them. This complexity highlights the need for greater consideration of sex offenders when planning projects and discussing homelessness policy, as even when there is political will to include sex offenders in a project, there are additional barriers to successfully integrating them.

Public Safety

Policymakers must also consider the public safety implications of congregating sex offenders in homeless encampments in parks, near schools, or on city streets. The importance of enforcing laws against unregulated street camping becomes even more apparent in light of the high proportions of sex offenders among the unsheltered population. Moreover, the evidence indicating extremely high rates of current criminal offending within the unsheltered population builds further urgency for a more proactive approach in moving people out of encampments and into shelters.82 Given the restrictions on admitting sex offenders to shelters, states and localities should consider developing plans to allow sex offenders to camp in a structured, secure environment or rely on criminal justice sanctions to ensure that this population is off the street. Another related option would be for states to make wider use of sexually violent predator statutes to civilly commit sex offenders who also exhibit behavioral health issues to psychiatric facilities.

Limitations and Further Research

This study relied on administrative data sets that varied considerably in structure, content, and labels. Sex offender registry data could not be independently verified beyond its status as official government data. In many states, not all sex offenders are included in public databases, potentially skewing the dataset in any number of different ways. The Point-in-Time Count data used to create the comparison datasets for general homeless populations are notoriously flawed methodologically. They could undercount, overcount, or simply miscount homeless populations, especially the unsheltered. This limitation almost certainly impacted this study, given the illogical outliers in Nebraska’s and Wisconsin’s results compared to unsheltered homeless populations.

This study did not investigate potential causes of variability among states, though future studies from the Cicero Institute will test several hypotheses based on its findings and the literature referenced herein. Moreover, the statistical analyses used in this study were basic and descriptive, in line with the goals of the study to identify sex offenders as a potentially significant subpopulation of homelessness. Far more research is warranted into the drivers of sex offender homelessness, causes of variability among states, and the impact of different proportions of sex offenders on program success, outreach, camping enforcement, and public safety concerns. All of these areas are of interest to future research by the Cicero Institute.

Conclusion

Sex offenders are a relevant subpopulation of homelessness that merits far more consideration by scholars and policymakers than they have been afforded. It is undeniable that sex offenders are an inconvenient and difficult population to discuss politically, and similarly difficult to work with in the community. But the alarmingly high numbers of homeless sex offenders across the country demand reconsideration of existing policies that may be ineffective when considering this information. There must be an urgency to develop innovative programs and policies to more assertively address the humanitarian and public safety crisis unfolding on the streets of America’s cities.

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about our fight for policies at the state level that restore liberty through transparency and accountability in American governance.