Rejecting AI Planning:

Policy to Promote Innovation and Protect the Vulnerable

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is now central to global economic competition, promising to unlock new productivity growth, enable medical breakthroughs, afford national security advantages, and open new frontiers for private enterprise. Worldwide AI investment surpassed $90 billion in 2021 and continues to grow at a remarkable pace of roughly 40-50 percent annually.1 In terms of compute—the hardware and energy fueling machine learning models—leading research labs report that the computational resources for cutting-edge AI have been doubling every six to nine months, far outpacing Moore’s Law.2 Even conservative estimates project that by 2030, AI could contribute between $13 and $15 trillion to global GDP, making it the most transformative economic force of the century.3

Unsurprisingly, most AI innovation is concentrated in the United States, followed closely by China, whose government aggressively subsidizes AI development to bolster economic growth and military competitiveness. Meanwhile, Europe’s share of venture funding for AI remains below 10 percent, lagging behind America’s roughly 60–70 percent share, due in large part to a strict regulatory environment that has deterred private investment and forced some European startups to relocate to friendlier jurisdictions.4 Indeed, the EU’s sweeping “AI Act” has been criticized for creating compliance costs so prohibitive that many entrepreneurs and financiers are looking elsewhere for opportunities. This divergence underscores how heavy-handed, preemptive regulation can push innovation to jurisdictions committed to a more balanced approach.

States should reject reflexive, top-down AI planning—where technology is controlled via sweeping rules and licensing regimes—in favor of a legislative strategy that:

- Targets specific, demonstrable harms

- Nurtures private-sector innovation, and

- Leverages AI to streamline government operations.

Section I lays out the Pathology of Planning in AI: why the urge to regulate everything upfront leads to regulatory capture, stifles competition, and could cede America’s leadership in AI to geopolitical rivals. Section II details Cicero Institute’s solution, which precisely addresses real harms while nurturing AI-driven growth and leveraging AI to achieve government efficiency. By adopting this strategy, states can safeguard against genuine risks, preserve America’s global edge in AI, and modernize government itself through efficient, AI-driven services.

PROBLEM: The Pathology of Planning in AI

“The ideology of governmental efficacy—that is, the view that government is, and must be, an effective agent for getting things done. Only a legislature committed to that ideology need act to solve problems in the face of pervasive uncertainties about their dimensions and their remedies.”

—Jerry L. Mawshaw, Regulation, Logic, and Ideology5

Central Planning’s False Promise in a Dynamic Tech Sector

Emerging technologies such as AI evolve at a blistering pace, defying neat definitions and static rules. Yet governments often feel tempted to “plan” and preemptively regulate such technologies, treating them as a problems to solve rather than as tools to unleash. This pathology of planning—an overreliance on top-down control—has a troubled history. In economic theory, central planning is inherently limited by the “knowledge problem,” which posits that no central authority can aggregate and process the dispersed information needed to govern a complex, changing system efficiently.6 Long before the world could reasonably conceive of the AI revolution, Friedrich A. Hayek warned this “knowledge problem” erects “an insuperable barrier” to effective central planning.7 In the context of AI, where innovations emerge from countless experiments in labs, startups, and open-source communities, a rigid plan can quickly become an obstacle rather than a guide.

Throughout history, major technological breakthroughs have often been met with panicked, misguided regulatory responses driven by fear of the unknown. Policymakers, with the best of intentions, have attempted to dictate outcomes or control new technologies, only to stifle progress or misallocate resources inadvertently. This reactionary impulse is evident today—states and nations are rushing to draft broad AI laws in the name of precaution. Such central planning in AI governance tends to overshoot—imposing rules based on speculative worst-case scenarios rather than empirical harms. The result is often a framework that is obsolete upon arrival. Indeed, AI is “an expansive and rapidly developing category…with no consensus definition and unclear boundaries.”8 By the time a bureaucracy defines what “counts” as AI, innovators have moved on. Any law risks being outdated almost as soon as it’s enacted, a reality that underscores the futility of heavy-handed planning in this arena.

The Costs of Premature and Heavy-Handed Regulation

The current trajectory of state-level AI policy in the United States highlights the problem. In recent years, state legislators have introduced a patchwork of AI-related bills—more than 700 across 45 states by one count—many aiming to curb algorithmic bias preemptively, require detailed algorithm audits, or even outright ban certain AI applications.9 This unprecedented flurry of activity represents an “unprecedented level of policy interest in preemptively regulating a new information technology,” and it stands in stark contrast to the approach the U.S. adopted for the internet.10 A generation ago, permissionless innovation was the prevailing ethos for the early internet: lawmakers chose restraint, allowing online services to flourish with minimal ex-ante (preemptive) regulation. That light-touch approach resulted in a “robust national marketplace of digital speech and commerce” and made American innovators world leaders in the tech sphere.11 By comparison, today’s reflex to regulate AI early and often risks reversing that successful formula.12

Heavy-handed or hasty AI regulations undermine economic growth and global AI competitiveness. AI is poised to be a major driver of productivity across industries—from healthcare and finance to manufacturing and agriculture. Overbroad rules or compliance burdens can chill investment and divert resources away from innovation. A “mother of all state regulatory patchworks” is on the horizon, which could burden startups with confusing, costly compliance requirements and “discourage entrepreneurialism and investment” in AI ventures.13 Small and mid-sized innovators, in particular, struggle to navigate a forest full of legal obstacles, leaving only well-lawyered tech giants able to navigate the thicket. This dynamic not only harms economic dynamism but also perversely entrenches incumbent firms, reducing competition. It is a classic case of regulatory capture in the making—where established players shape and survive regulation while upstarts are kept out. Even the creation of new AI oversight agencies could backfire.

As a Mercatus Center study cautions, adding a “new opaque authority with potentially extensive power” over AI would invite capture by special interests that are “antithetical to the public interest,” creating new problems while ignoring or exacerbating old ones.14 In short, an expansive AI regulatory regime may become a playground for lobbyists and lawyers rather than a safeguard for the public.

International experience validates these concerns. The European Union’s recently passed AI Act represents the most comprehensive attempt at centralized AI governance—and a cautionary tale. The EU’s “sweeping set of regulations” uses a risk-based approach that sounds reasonable in theory, but, in practice, its expansive definition of “high-risk” AI casts a wide net. The law can classify even general-purpose AI models as having “systemic risk” under vague criteria.15 While meant to protect against AI harms, this approach seals Europe’s fate as a digital laggard. The lesson is clear: overbearing AI rules can drive away the very innovators we need, undermining a country or state’s long-term economic vitality.

Regulatory Capture and Unintended Consequences

Overregulation not only stifles innovation but also breeds bureaucratic pathologies that defeat the regulation’s purpose. One of these is regulatory capture, where instead of serving the public, regulators come to serve the industry or special interests they oversee. This is a well-documented phenomenon in economic literature and a particular risk in the tech sector, where technical expertise is at a premium. Suppose a state creates, for example, an AI licensing board or an algorithm review commission. In that case, there is a real danger that such a body could be dominated by established companies or advocacy groups seeking to bend the rules in their favor. The history of telecommunications, finance, and other regulated industries shows that well-intentioned oversight bodies can be co-opted, leading to higher barriers to entry and regulations that favor the few instead of the many. In the AI context, that could mean freezing the current leaders and approaches in place and smothering the adaptive, evolutionary processes that characterize true innovation.

If states pursue sweeping regulatory frameworks rather than targeted interventions in AI, the beneficiaries will be Big Tech giants, and the losers will be consumers and innovators. When regulatory agencies wield new powers, bureaucrats become attractive targets for industry giants who have the resources and influence to access and shape regulations to their advantage. Rather than resist new compliance burdens, these incumbent firms actively lobby for unbalanced rules and enforcement, knowing that high costs bulwark their monopolies and oligopolies.

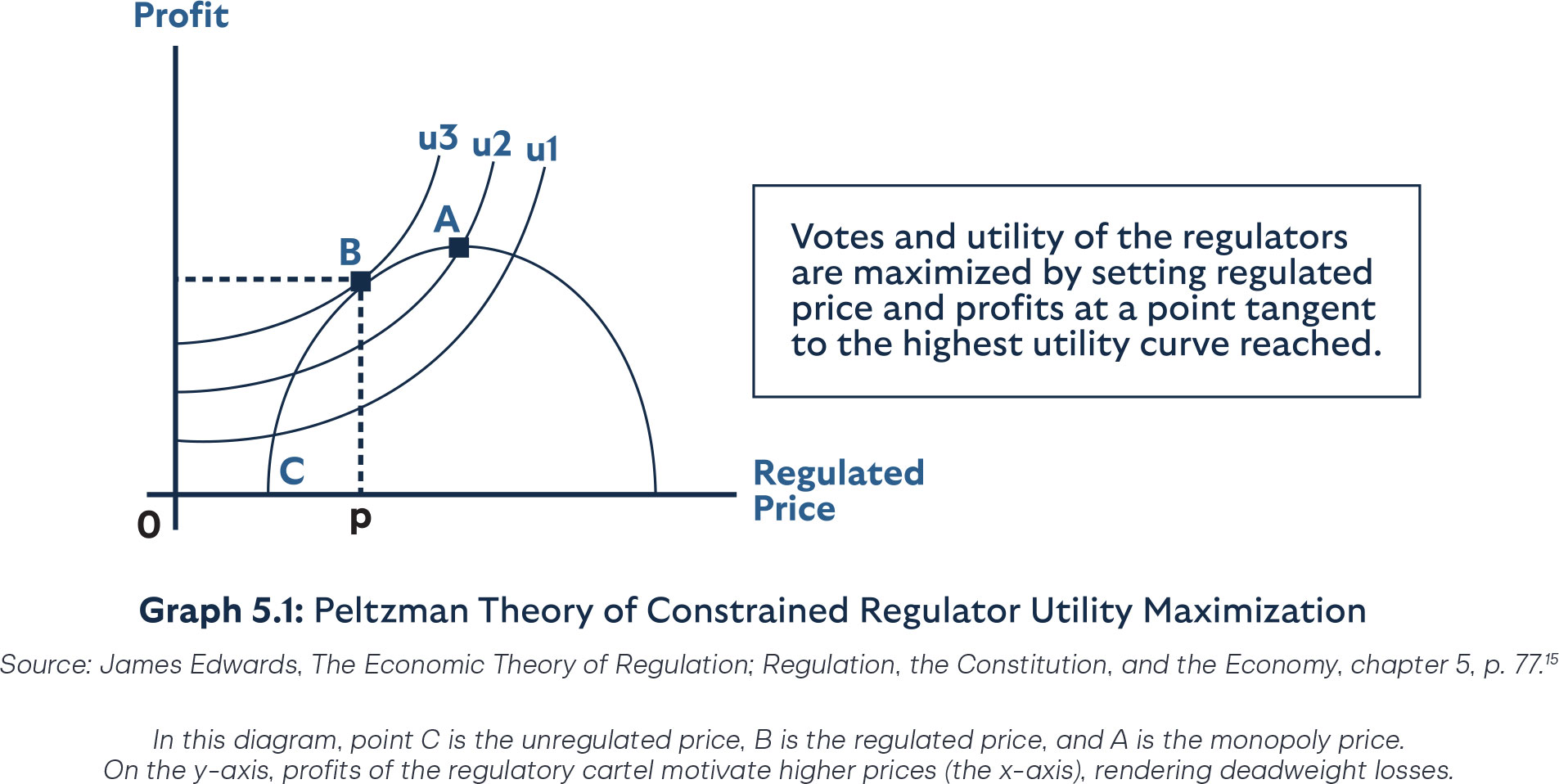

Consumers stand to lose the most, enjoying less choice and facing higher prices in a captured market. UChicago Economist Sam Pelzman famously pointed out that profits of this “regulatory cartel”—rent-seeking interest groups and career-or political-minded regulators—come at the expense of market equilibrium (Graph 1). In short, while regular citizens and disruptive founders have access to their elected lawmakers, only the most entrenched interests have access to overpowered regulators, weaponizing expansive and legally uncontested rulemaking to distort price signals and fortify market failures. As capture yields deadweight losses, suboptimal market conditions then invite a feedback loop that yields even more regulation.

Moreover, the complexity and opacity of AI systems provide convenient cover for bureaucratic overreach. Regulators might demand algorithmic “transparency” or audits, yet as researchers point out, requiring innovators to get “constant permission from a number of different regulators” at each stage of algorithm development would “ultimately backfire…by slowing innovation.”16 It creates a false sense of security—a belief that government overseers can fully understand and control AI—while, in reality, outsourcing trust to “faraway bureaucrats” introduces a new opacity.17 The public may know even less about how decisions are made if everything goes on behind closed regulatory doors. This “transparency paradox,” as the Mercatus scholars term it, means that calls for algorithmic accountability could paradoxically result in a regime that is less transparent and less accountable than the status quo.18 And once entrenched, such a regime would be difficult to reform—as the “harder-to-reverse methods of capture” in administrative law attest.19

Threats to U.S. Technological Leadership

As mounting national debt poses a growing threat to America’s security and economic stability, the stakes for AI innovation extend beyond market competition. The United States’ position as a global leader in AI is neither guaranteed by birthright nor immortal—it stems from a long cultivated environment that rewards bold thinking and calculated risk. If that environment shifts toward an overly burdensome regulatory framework, it will invite adversarial nations, notably China, to seize global leadership. Beijing is actively channeling vast resources into AI, but for ends often at odds with American values. To maintain our technological edge and unlock AI’s potential for boosting productivity—thereby helping to address our debt-driven national security challenges—America must avoid self-inflicted damage through poor policy choices. Concretely, this means ensuring that top talent, investment, and companies can thrive on American soil under rules that encourage innovation rather than suppress it. Any regulatory overreach—say, making AI deployment unworkable in healthcare or finance—will inevitably prompt entrepreneurs to seek friendlier jurisdictions, granting rivals the upper hand.

Nor is this merely a contest of economic power. AI will embody the principles of the societies that refine and deploy it, and if the United States allows rigid rules to strangle development, it risks forfeiting leadership in setting global norms. By remaining an epicenter of AI progress, America can shape these technologies in accordance with openness, transparency, and respect for personal liberties—thereby outmaneuvering authoritarian models. As Heritage Foundation analysts note, the world needs guardrails for AI that are “imbued with American values like openness,” rather than leaving the field to authoritarian “AI-for-control” regimes.20

Thus, from both an economic and strategic standpoint, the U.S. must be wary of policies that respond to AI with the knee-jerk impulse to police and control at the expense of progress. We cannot cling to the illusion of control through burdensome regulations without jeopardizing our innovation ecosystem, global standing, and foundational values.

Government Inefficiency and the Innovation Gap

Ironically, while many governments rush to regulate AI, they often neglect opportunities to leverage AI for their own efficiency and public service improvements. The pathology of planning is evident not only in overregulation but also in the public sector’s sluggish adoption of innovation. Many state agencies operate with outdated systems and processes, missing out on AI tools that could enhance government efficiency and accountability. For example, AI applications can help agencies process data faster, reduce fraud in benefit programs, handle routine inquiries via chatbots, and assist human decision-makers with insights. Yet bureaucratic inertia and fear of the unknown frequently hold back these advances.

In some cases, overly stringent rules or a lack of clear guidance prevent agencies from experimenting with AI that could improve their operations. One problem is the absence of a coherent strategy: agencies may not even be aware of all the AI tools in use across the government. No single office or official is tasked with identifying redundant efforts, unmet needs, or best practices for AI deployment in state services. This internal lack of coordination is a policy failure in its own right—a form of planning without vision. Just as central economic planning fails for lack of real-time knowledge, government modernization fails when agencies operate in silos.

The problem is two-fold: on one hand, heavy-handed AI regulation threatens to hamstring innovation, invite regulatory capture, and undermine economic growth. On the other hand, the public sector’s inefficiency and failure to embrace innovation leave potential gains on the table. The pathology of planning manifests as an impulse to control what is new and a paralysis in updating what is old. Both trends jeopardize the promise of AI to enhance prosperity and public welfare. Americans require a course correction that addresses legitimate concerns without succumbing to the false allure of centralized control.

SOLUTION: A Balanced Legislative Blueprint to Spur Innovation and Protect the Public

Having diagnosed the pathology of planning in AI—overregulation that stifles innovation, bureaucratic capture, and missed opportunities for government modernization—states require a nuanced legislative strategy that targets real harms while nurturing AI-driven growth and agency efficiency. The AI Innovation and Child Protection Act presented here achieves precisely that. By (1) streamlining government operations, (2) restraining new AI-specific regulations without express legislative approval, and (3) criminalizing genuinely harmful AI uses, the Act addresses both the innovation imperative and the urgent need for concrete safeguards—particularly around child sexual abuse materials and self-harm promotion. Below is a line-by-line explanation of how each section solves the core problems outlined in Section II.

Government Efficiency and Modernization

Why It Matters

States often miss the chance to modernize their agencies, bogged down by archaic processes and risk aversion. This section directs an active pivot:

- Agencies must incorporate AI to cut costs and slash red tape.

- They cannot complicate private-sector AI adoption by introducing extra licensing boards or “pilot fees”—incentivizing them to be facilitators, not obstructionists.

- They must rely on existing staff and resources as a check against ballooning bureaucracy.

This arrangement addresses the innovation gap in the public sector, ensuring that AI-based reform is championed by the governor’s office rather than entangled in new layers of oversight. The slashing of unnecessary AI barriers parallels success stories like Idaho’s regulatory reset.21–22

Virginia, in particular, leads in the piloting of AI among government agencies as well as establishing clear governance and procurement procedures for state government deployment. By compelling agencies to actively prune outdated rules, section four fosters a clear, innovation-friendly climate.

Regulatory Limitations

Why It Matters

A Core Fix to the Problem of Top-Down AI Planning

Rather than allowing agencies spontaneously to overregulate under ambiguous mandates, our model restricts new AI rules unless the legislature has explicitly identified a real, specific harm. By demanding that “benefits clearly outweigh impacts,” the Act effectively sets up a cost-benefit test akin to robust economic scrutiny. Simultaneously, it blocks regulatory capture by requiring that rules “do not create barriers to market entry or advantage incumbents.”

Additionally, any “emergency rule” must be ratified quickly, preventing indefinite placeholders from slipping into permanence. This principle comports with many successful state reforms, where deregulatory sunsets force a reevaluation of each rule’s necessity. Consequently, our model erects a strong bulwark against reactionary or captured rulemaking, ensuring that market competition and innovation remain paramount.

Criminal Law

Why It Matters

This clarifies that existing penal codes still hold criminals accountable, even if AI is involved. If an individual orchestrates fraud, identity theft, or harassment via an AI tool, traditional statutes remain in play. That approach obviates the need for a separate “AI penal code,” alleviating concerns that new legislation might complicate existing enforcement or let criminals claim “the AI did it.” By reinforcing that AI is merely another instrument, our model strengthens public safety without redundant legal expansions—mirroring successes in states that rely on existing laws to cover emerging crimes.

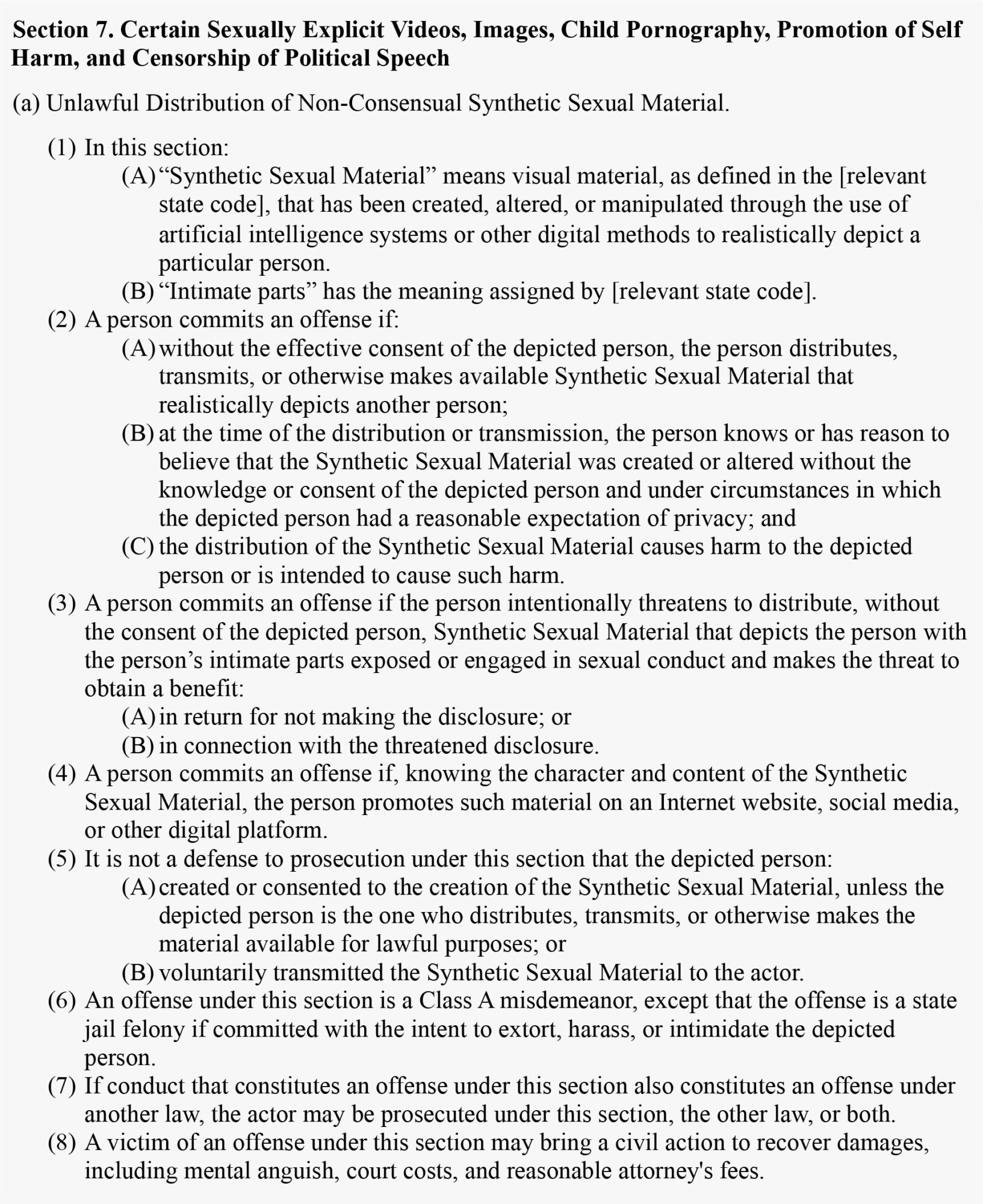

Certain Sexually Explicit Videos, Images

Why It Matters

Deepfake revenge porn is a real, expanding threat, especially with modern generative models producing lifelike sexual images from minimal data. This clause criminalizes AI-based sexual violations, ensuring offenders cannot hide behind claims of “fictional content.” By giving victims a civil cause of action, it also empowers them to seek damages promptly.

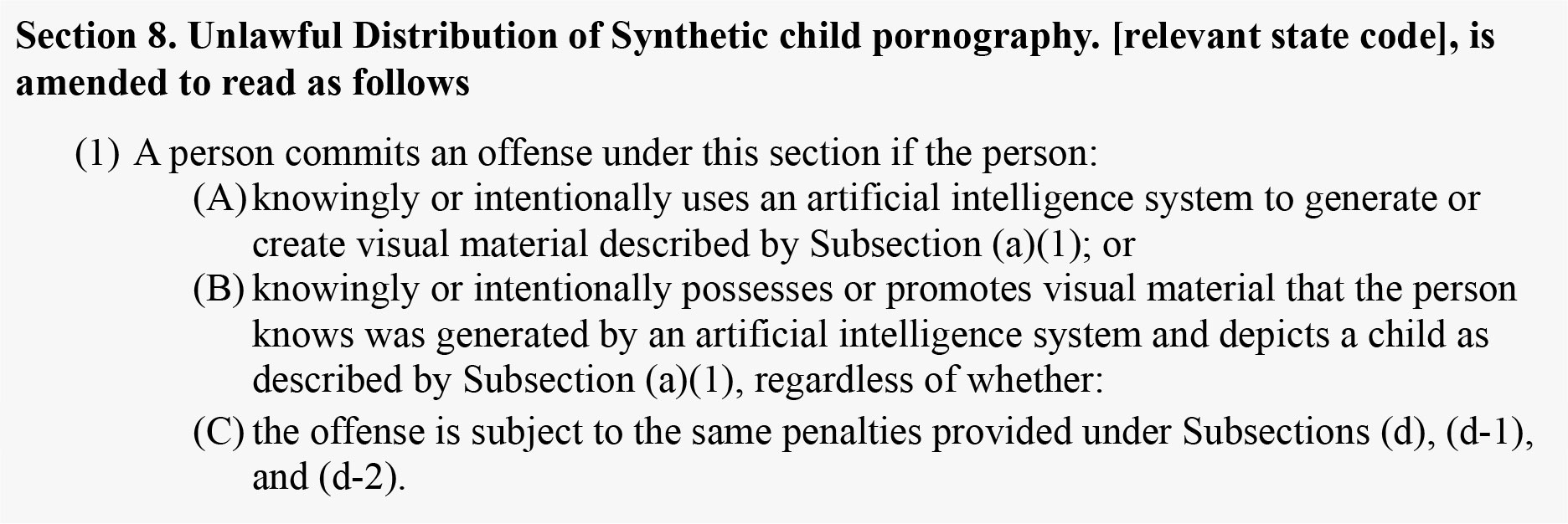

Child Pornography

Why It Matters

Standard child pornography laws often presume an actual human minor’s involvement, potentially leaving loopholes for AI-generated images. This section explicitly outlaws synthetic child sexual imagery. The stiff penalties effectively close that loophole, protecting minors (real or hypothetical) and stopping predators who exploit new AI tools.

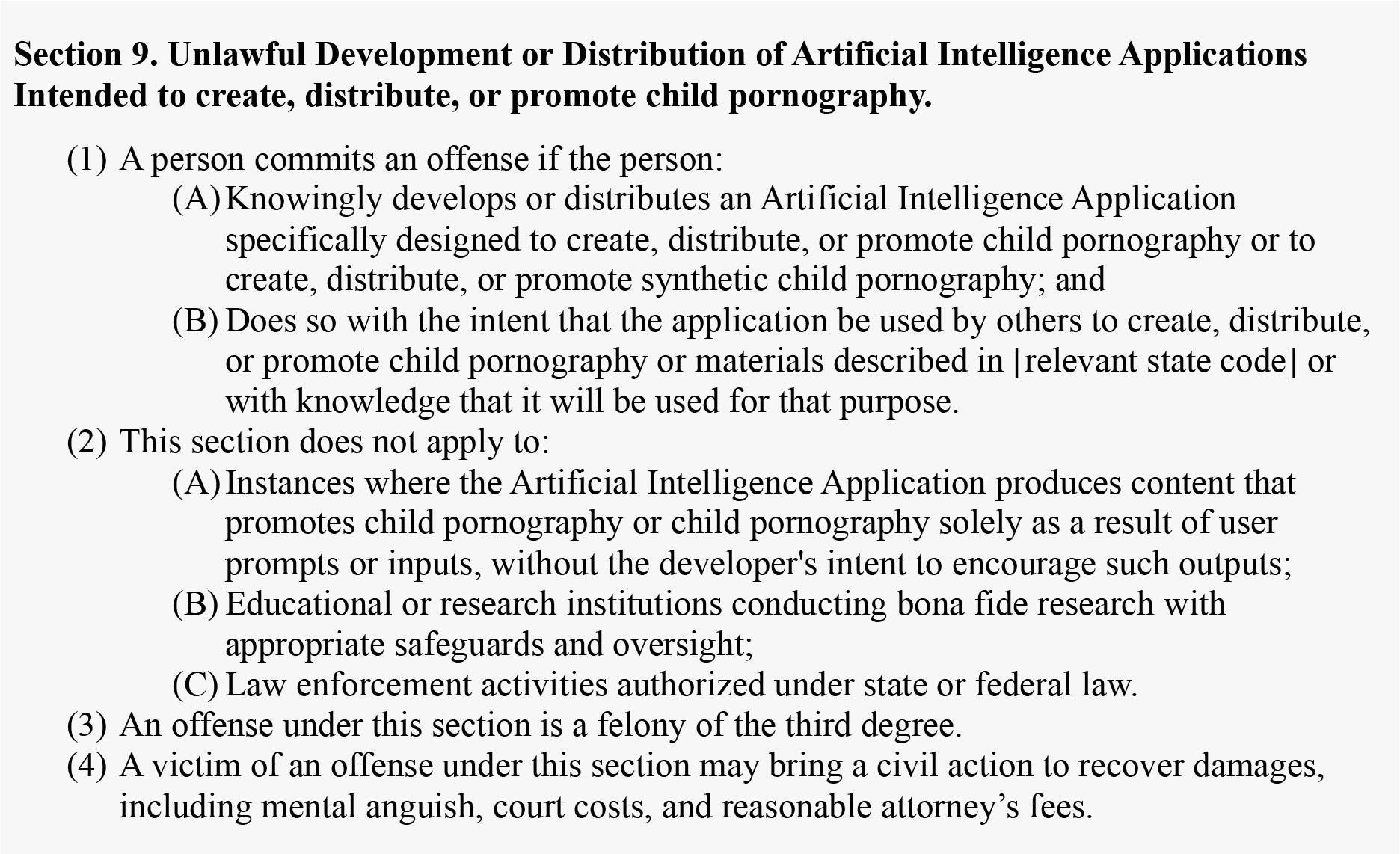

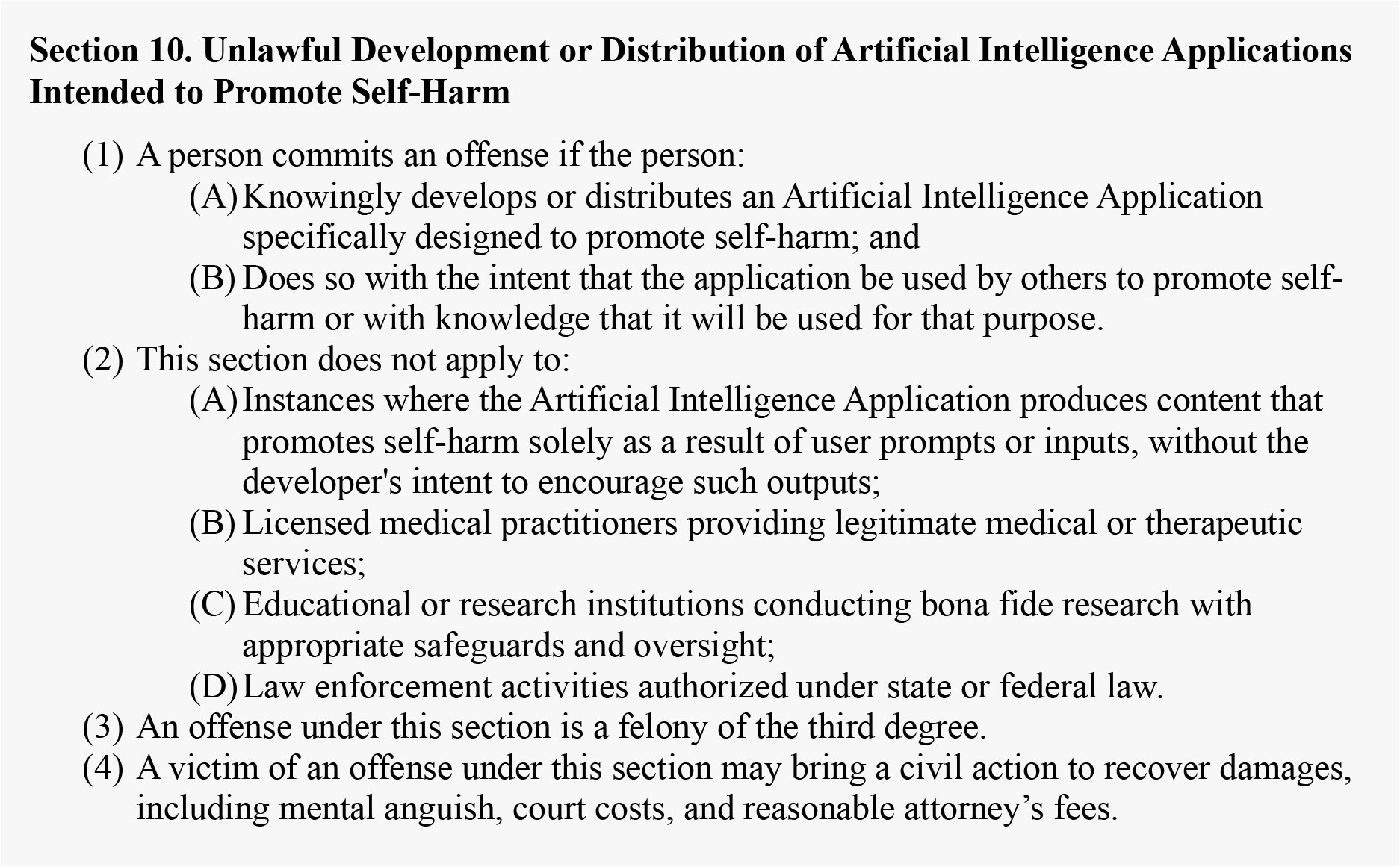

Child Pornography Continued and Promotion of Self Harm

Why It Matters

Sections (c) and (d) clamp down on the supply side of malicious AI apps. By extending liability to those who intentionally build and distribute tools enabling child pornography or self-harm promotion, the Act deters would-be creators of harmful software. At the same time, legitimate mental health uses are exempted, preserving therapeutic AI that actually prevents self-harm.

Censorship of Political Speech

Why It Matters

Finally, AI-based content moderation can silence views or stoke biases in online discussions. This subsection bans viewpoint-based discrimination when AI is used, simultaneously carving out exceptions for illegal or violent materials. For a democracy reliant on open debate, this ensures robust speech remains protected, preventing unaccountable machine-learning systems from de-ranking or demonetizing certain political perspectives. By imposing civil penalties, Section 7(e) enforces meaningful compliance without crippling a platform’s capacity to remove truly unlawful content.

Liability Protection for AI Application Developers

Why it Matters

Lawsuits arising from third-party actions may stifle innovation and limit the AI tools that are put into the market. It is not reasonable to expect developers to predict every scenario for which end users may use an AI tool, especially those that serve a broad or general purpose, such as LLMs. Most recognize that cars and kitchen knives have great utilitarian purposes, but in the hands of the wrong user, can be weapons deployed to inflict damage. Similarly, there are a multitude of ways an AI application, tool, or system could be used for illegal or illicit activities resulting in harm. America’s product liability framework is well developed elsewhere—for physician tools, cars, knives, etc.—actions by a third party using tools for illegal activities will not result in liability to the creator of that tool. The same reasoning applies in AI. States can make clear that AI app developers should be provided the same protection, with limited exceptions, such as if that tool was developed with the primary purpose of being used for illegal or illicit activity.

Preemption and Severability

Why It Matters

Minimizing patchwork regulation is essential. States that allow localities to adopt contradictory AI ordinances confuse agencies and startups. By preempting local rules on AI, the Act creates a stable statewide environment, akin to how many states handle ride-sharing or telehealth. The severability clause ensures that if a court strikes one part, the rest remains intact—thereby preventing legal challenges from unraveling the entire framework.

Conclusion: Fostering Innovation While Guarding Against Regulatory Pitfalls

The AI Innovation and Child Protection Act presented herein stands as a coherent, action-oriented framework for state policymakers grappling with both the promise and the perils of AI. Its hallmark is precision—encouraging economic dynamism and modernization in section four, limiting overregulation via section five, leveraging existing criminal laws in section six, and surgically outlawing malicious AI uses in section seven. By expanding the public sector’s own AI adoption, it converts state government from an inhibitor to a champion of innovation, all while blocking the destructive potential of so-called “deepfake” sexual content, AI-facilitated child pornography, and self-harm applications.

In direct response to the pathology of central planning, this Act shields entrepreneurs from capricious rules, empowers agencies to adopt AI responsibly, and protects citizens from malicious AI-based threats. In short, it carefully targets specific, demonstrable harms without stifling the free development of AI. For states aiming to retain their economic leadership, ensure public safety, and preserve American competitiveness in AI, the AI Innovation and Child Protection Act serves as a practical, flexible solution—one that unlocks AI’s vast potential while addressing legitimate fears.

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about our fight for policies at the state level that restore liberty through transparency and accountability in American governance.