Involuntary Civil Commitment

Introduction

Mental illness is a central driver of the homelessness crisis unfolding across the United States, especially among the chronically homeless and unsheltered populations that Americans encounter on city streets. In 2022, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development concluded that 21 percent of the total homeless population suffers from severe mental illness. A greater portion, 24 percent, of the unsheltered population struggles with severe mental illness.1

One of the largest studies of homelessness found that more than half of unsheltered homeless individuals reported serious mental health issues that contributed to their loss of housing, including depression, anxiety, hallucinations, and trouble with basic mental functions like understanding and memory.2 Despite this, few receive any treatment—only 14 percent received outpatient treatment or counseling, and 20 percent were prescribed medication for mental health issues.3 Several studies indicate that homeless individuals who are severely mentally ill are among the most vulnerable: they experience the highest likelihood of victimization (74–87%) as well as the highest likelihood of facing arrest (63–90%).4

Some of these individuals face such severe symptoms that they become dangerous or are quickly deteriorating to such a state. This depth of mental illness often keeps a person from consenting to treatment, often either because of anosognosia—a condition that impairs one’s ability to perceive his or her illness—or other impairing factors.5 To address this issue, states have created laws that allow families, law enforcement, and other interested parties to petition for an individual to be evaluated by mental health professionals and, if their condition is severe enough, involuntarily committed for treatment. Involuntary civil commitment is an essential tool to help people who are experiencing homelessness and severe mental illness receive the treatment they need to survive.

Use of Involuntary Civil Commitment

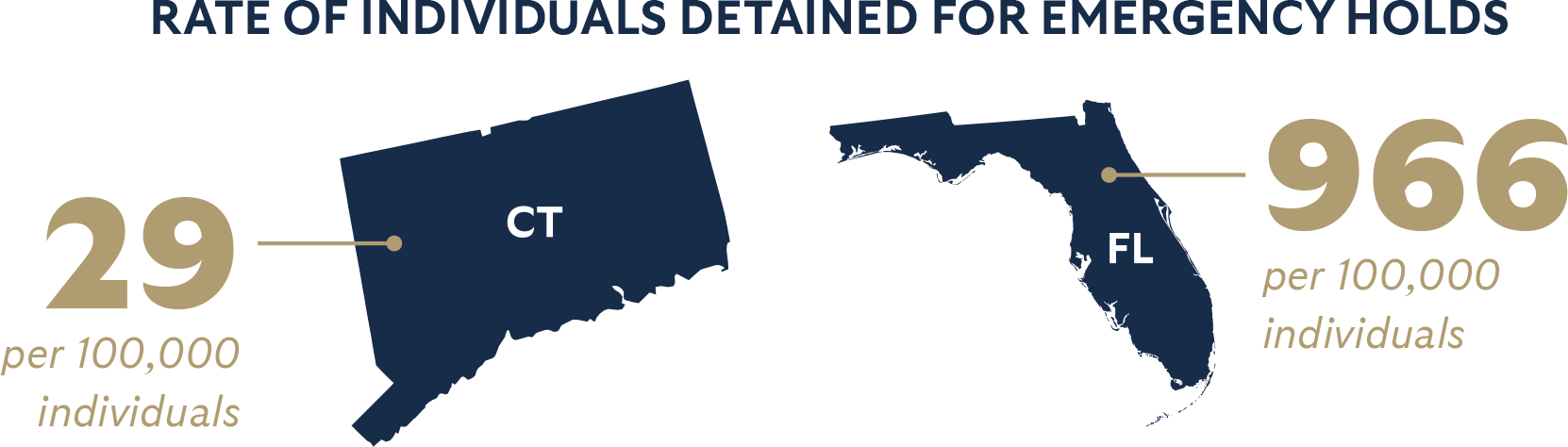

There is a wide range in the quality of involuntary commitment laws around the U.S. This is shown in how widely states range in commitment rates, from 0.23 to 43.8 per 1,000 persons with serious mental illness in Hawaii and Wisconsin, respectively.6 The national average is approximately nine in 1,000. The rate of those detained for emergency holds also varied dramatically between states, from 29 per 100,000 individuals in Connecticut to 966 per 100,000 in Florida. The national average for detentions is 357 per 100,000.7

Types of Involuntary Commitment

There are three main parts of involuntary treatment:

- Emergency Detention: A short-term emergency hold in a hospital so a medical evaluation of an individual can be performed.

- Inpatient Commitment: Court-ordered treatment in a psychiatric hospital.

- Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT): Court-ordered treatment outside of a psychiatric hospital, allowing the individual to continue living on their own with assistance.

Intake Process

The particulars of each type of commitment depend on each state’s laws, but, generally, an individual is taken to the hospital to be stabilized by a family member, law enforcement, or emergency medical services. They are then placed under involuntary detention, or “emergency hold,” during which medical professionals evaluate their health and needs. The evaluation determines whether the individual qualifies for further detention and treatment.

At this point, the individual may accept treatment voluntarily or may not qualify for further treatment. Those who do not accept treatment but qualify for involuntary commitment are held for a few hours to a few days until a court hearing. If the court rules in favor of the medical professional’s recommendation, only then is a person involuntarily committed. Otherwise, they may qualify for assisted outpatient treatment, which they can be court-ordered to participate in if the individual will not participate voluntarily.

Criteria for Involuntary Commitment

Emergency Hospitalization for Evaluation

Criteria for eligibility to be detained for evaluation should not be more restrictive than the state’s inpatient commitment standard and should allow private individuals to petition the court for an evaluation. This frees families from being forced to wait for the individual to exhibit the sort of violent behavior that tends to draw police attention.

Inpatient Commitment

There are two common standards for inpatient treatment: grave disability and need for treatment.

- The “Grave Disability” standard is met when a person poses a physical threat to themselves through inability (other than for reasons of indigence) to provide for the basic necessities of human survival, just as surely as if they were actively trying to harm themselves.8

- The “Need-For-Treatment” standard is met when a person experiences a deterioration of mental health, psychiatric damage, and loss of ability to function independently—all of which typically follow when severe mental illness goes untreated. Typically, a need for treatment standard requires a finding that a person’s mental illness prevents him or her from seeking help on a voluntary basis and, if not treated, will cause the individual severe suffering and harm his or her health. Need-for-treatment laws make commitment available to the person who suffers greatly from severe mental illness, even if the individual manages to meet their own basic survival needs and exhibits no violent or suicidal tendencies.

One important component of inpatient commitment criteria is who is legally allowed to petition the court for someone to receive treatment. Private individuals—rather than professionals—are often in a better position to know someone’s baseline of behavior and functioning, psychiatric history, triggers, signs, and symptoms of deterioration or crisis, which provides key context for the judge alongside the required professional evaluation. States should broaden who can petition for commitment to any concerned adult familiar with the individual of concern (which includes social workers), or at least broaden it from professionals to include family or household members.

Other important factors include the duration of treatment. States should allow the initial period of inpatient commitment to exceed 30 days to properly stabilize an individual and create a comprehensive plan for their care.

Assisted Outpatient Treatment

The criteria for someone to be committed to assisted outpatient treatment is distinct from inpatient commitment criteria because it is for individuals who do not qualify for involuntary civil commitment. Assisted outpatient treatment addresses the needs of those who may not be demonstrably dangerous but have a clear need for treatment and have a documented history of failing to adhere to treatment.

Most states authorize assisted outpatient treatment, but three states—Connecticut, Maryland, and Massachusetts—do not.

The criteria for assisted outpatient treatment varies, but the strongest frameworks include the following:

- Accountability for individuals who refuse to adhere to the requirements of AOT.

- Allow family members and others familiar with the individual to petition the court for AOT.

- Empower courts to order AOT for greater than six-month durations.

Capacity

Many states need to add more psychiatric beds so that there is enough capacity to accommodate the levels of need in the population, especially among homeless individuals. The United States has, on average, fewer than 12 psychiatric beds per 100,000 people—fewer than at any point since the 1850s. Approximately half of these beds are in prisons and other correctional facilities. Peer nations have significantly greater mental health resources, with Germany providing 128 beds per 100,000 people and the European Union providing, on average, 73 beds per 100,000 people. Experts estimate that the U.S. should aim for approximately 50 beds per 100,000 people and robust outpatient resources.

In addition to adding psychiatric bed capacity, states should build out a full continuum of mental health care to better address the specific needs of a diverse and complex population.

A multi-pronged plan to increase capacity includes:

- Adding capacity of inpatient psychiatric beds based on state-specific data (prevalence of severe mental illness). These beds could be in public or private institutions.

- Expand community-based services that support and integrate patients who are stable medically but not socially back into the community. This could include housing assistance, case management, and peer support. Medicaid can play a significant role in reimbursement through 1915(i) State Plan Amendments as well as state-based vouchers.

- Expand smaller treatment providers, both in the areas of severe mental illness and addiction treatment.

Results on Effectiveness

Involuntary treatment methods, including involuntary civil commitment, have been found to significantly reduce homicides, improve long-term outcomes, and reduce crime. In 2011, a state-level study on commitment standards and homicide rates found a significant reduction of homicides in areas with broader involuntary civil commitment criteria, with 1.42 fewer homicides per 100,000 people.9

Another study found that longer hospital stays significantly improve outcomes as far as the likelihood of being re-hospitalized, encouraging legislation that allows for longer hospital stays for those who need longer time in treatment.10

The lack of resources necessary to proceed with involuntary commitment is also keeping individuals from receiving the care that they need. In particular, reduced access to psychiatric inpatient beds was associated with a 24 percent increase in homicide rates. Another study concluded that as state hospital bed capacity decreased, the number of mentally ill homeless individuals increased, as well as crime and arrests associated with homelessness.

For individuals who do not quite need involuntary civil commitment but have demonstrated difficulty engaging with treatment voluntarily, Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT) is an effective way to provide people the help they need. A Duke study identified that those who underwent sustained periods of intensive outpatient commitment beyond that of the initial court order had approximately 57% fewer readmissions and 20 fewer hospital days than control subjects.11 The US Department of Justice defines AOT as best practice.12

Other studies on the experience outcomes of participants in AOT reveal broadly positive results. Additionally, AOT avoids resource constraints that have long plagued mental health systems, such as the lack of beds, and has been found to be cost-effective.

These studies indicate that involuntary care interventions offer individuals the treatment they so desperately need to help them recover. This has not been found to be the case for Housing First approaches to those struggling with mental illness. Stergiopoulos and colleagues (2015) found that Housing First participants did not have any difference in outcome on measures of severity of mental health symptoms, self-rated mental health status, community integration, or degree of recovery compared to the control group.13 Another study found that 12 percent of Denver permanent supportive housing program participants died over three years, compared to eight percent in the control group who did not enter the program.14

Conclusion

Protecting individual liberty with due process is integral to the proper use of involuntary civil commitment. Still, our laws must be efficient and effective enough to accommodate homeless individuals with complicated needs. Moreover, many states do not have adequate capacity in their mental health systems to address the demand for treatment in their communities. Policymakers should invest in building a continuum of treatment capacity in state mental health systems. Involuntary civil commitment laws provide an essential pathway to treatment for the most vulnerable people in our communities.

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about our fight for policies at the state level that restore liberty through transparency and accountability in American governance.