Homelessness in Missouri: An Evolving Crisis

In Missouri, the previous decade has brought new challenges for communities struggling with homelessness. While today total homelessness is marginally lower than 10 years ago, homelessness has been getting worse in Missouri since 2018, rising 22.8 percent over five years.1 Moreover, the number of unsheltered homeless—the most vulnerable subgroup of the homeless population—has grown by 38.7 percent since 2013 and 77.7 percent since 2018.2 And today, fewer homeless Missourians have access to shelter than a decade ago: one in four homeless people were without shelter in 2013, but today that figure is now more than one in three.3

Missouri’s approach to homelessness policy is not working, and Missouri needs new solutions. But in order to address this crisis appropriately, it is imperative that policymakers are aware of the major trends in both the homeless population and in its capacity to respond.

Composition of Missouri’s Homeless Population

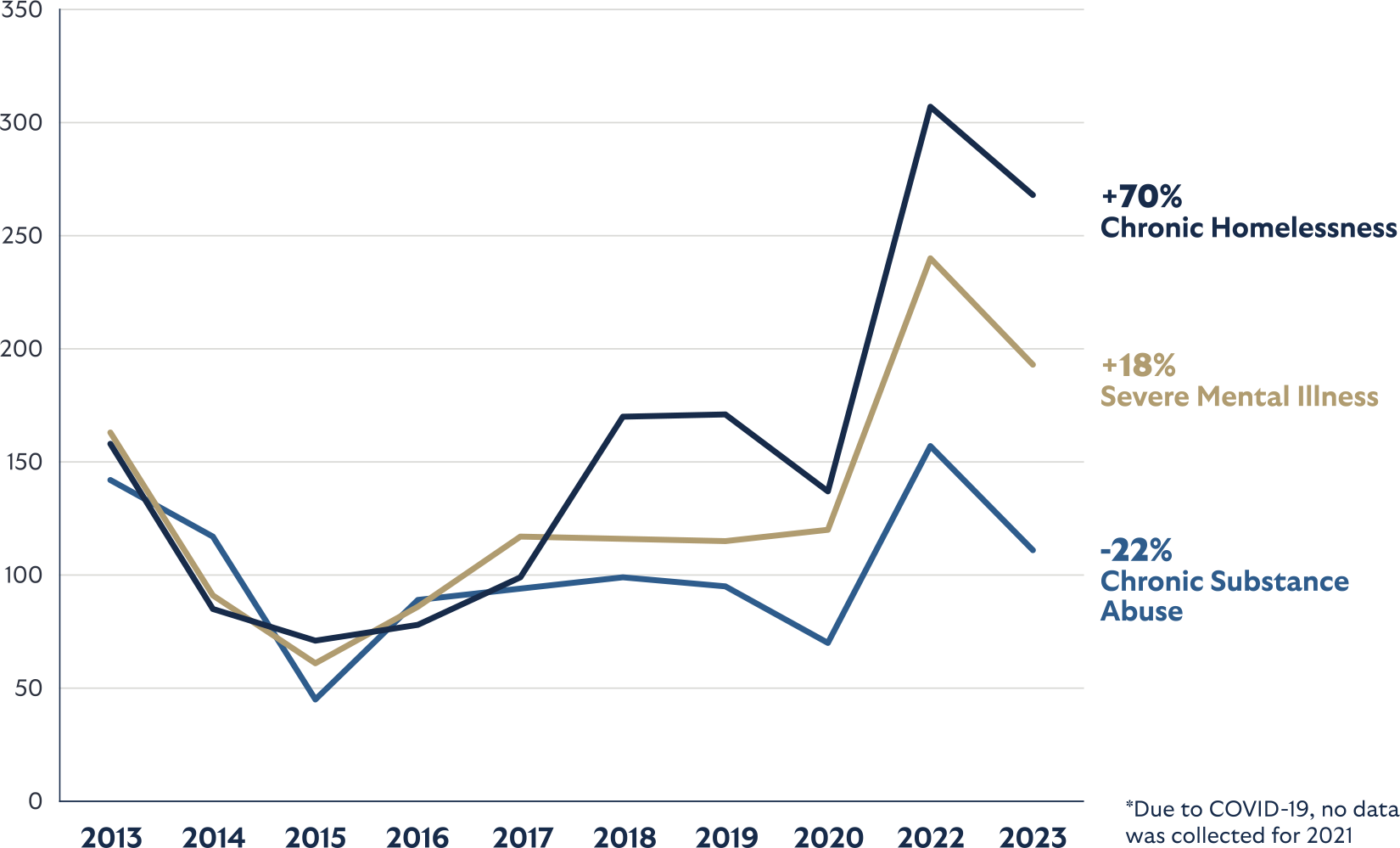

The alarming growth of unsheltered homelessness in Missouri dwarfs the changes in homelessness overall. There are many factors to consider in analyzing this trend, but among the most compelling are chronic substance abuse levels, the prevalence of severe mental illness, and categorization as “chronically homeless,” which is defined as a homeless individual with a disability who has been homeless for at least one year, or on four separate occasions in the last three years, including those whose homelessness was interrupted by periods of stays in hospitals, mental health institutions, or correctional institutions. These categories capture the highest need subset of an already vulnerable population, and the way that their measures have changed offers insight into the limitations of current policies and obligations for future policies.

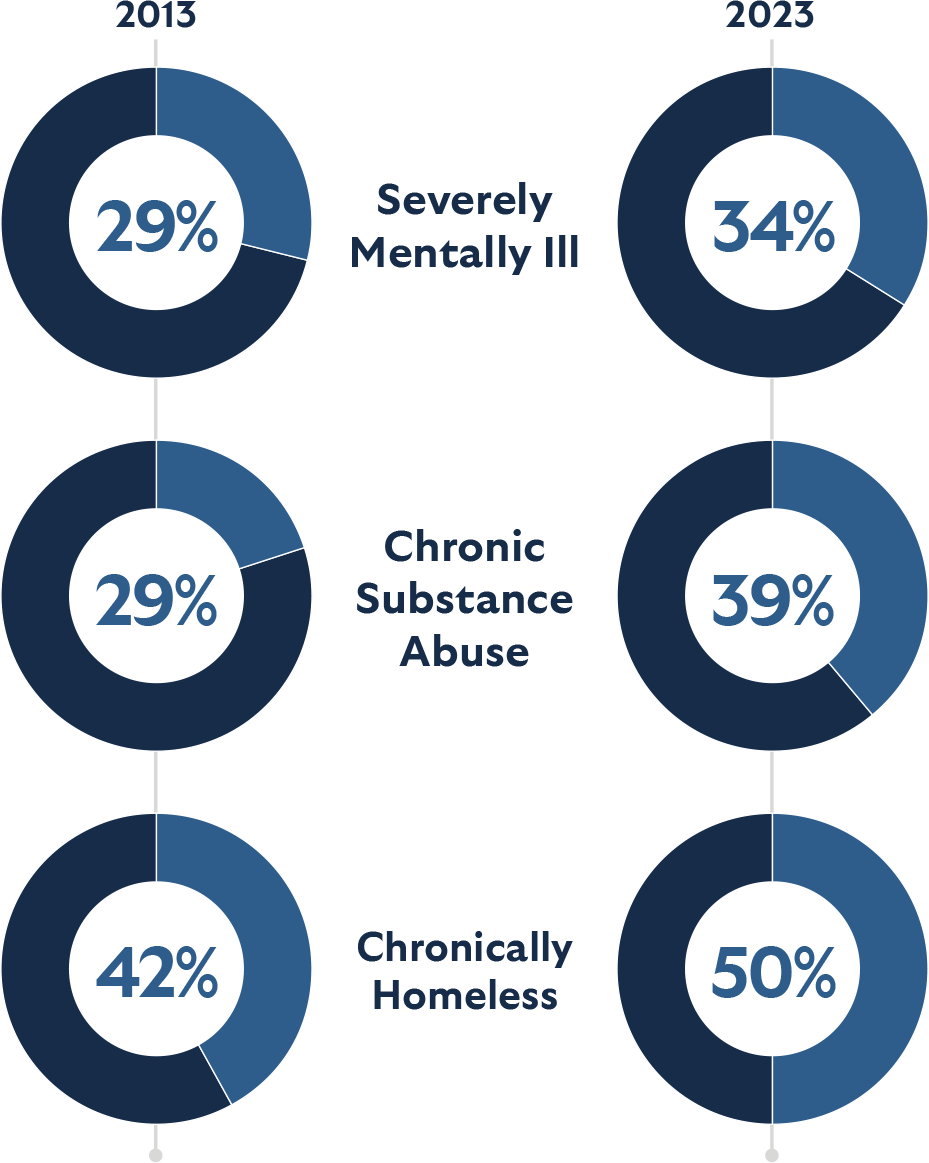

Today, more unsheltered homeless Missourians fall into the categories of chronic substance abuse, severe mental illness, and chronic homelessness than in 2013 or 2018.4 But there are also more homeless people with each of these challenges who are without shelter, which implies that a growing number of homeless individuals who would have been sheltered in the past are falling through the cracks of existing services and ending up on the street. Figure 1 shows the changes in the proportion of homeless individuals who have a severe mental illness, struggle with chronic substance abuse, or are chronically homeless and without shelter in Missouri over the past decade.5

A greater share of homeless people with severe mental illness are without shelter today than 10 years ago, which calls into question the effectiveness and capacity of existing services to meet the needs of severely mentally ill homeless individuals. The situation for homeless people with chronic substance abuse is far worse, with the proportion of that subpopulation without shelter nearly doubling since 2013. And chronically homeless individuals are also worse off today than 10 years ago, with a 19 percent increase in the proportion of that subpopulation that is without shelter. These trends indicate the increasing needs of the homeless population and reveal some of the limitations of the current approach to homelessness policy.

Figure 1: Unsheltered Homeless 2013–2023

Capacity of Missouri’s Shelters and Housing Assistance

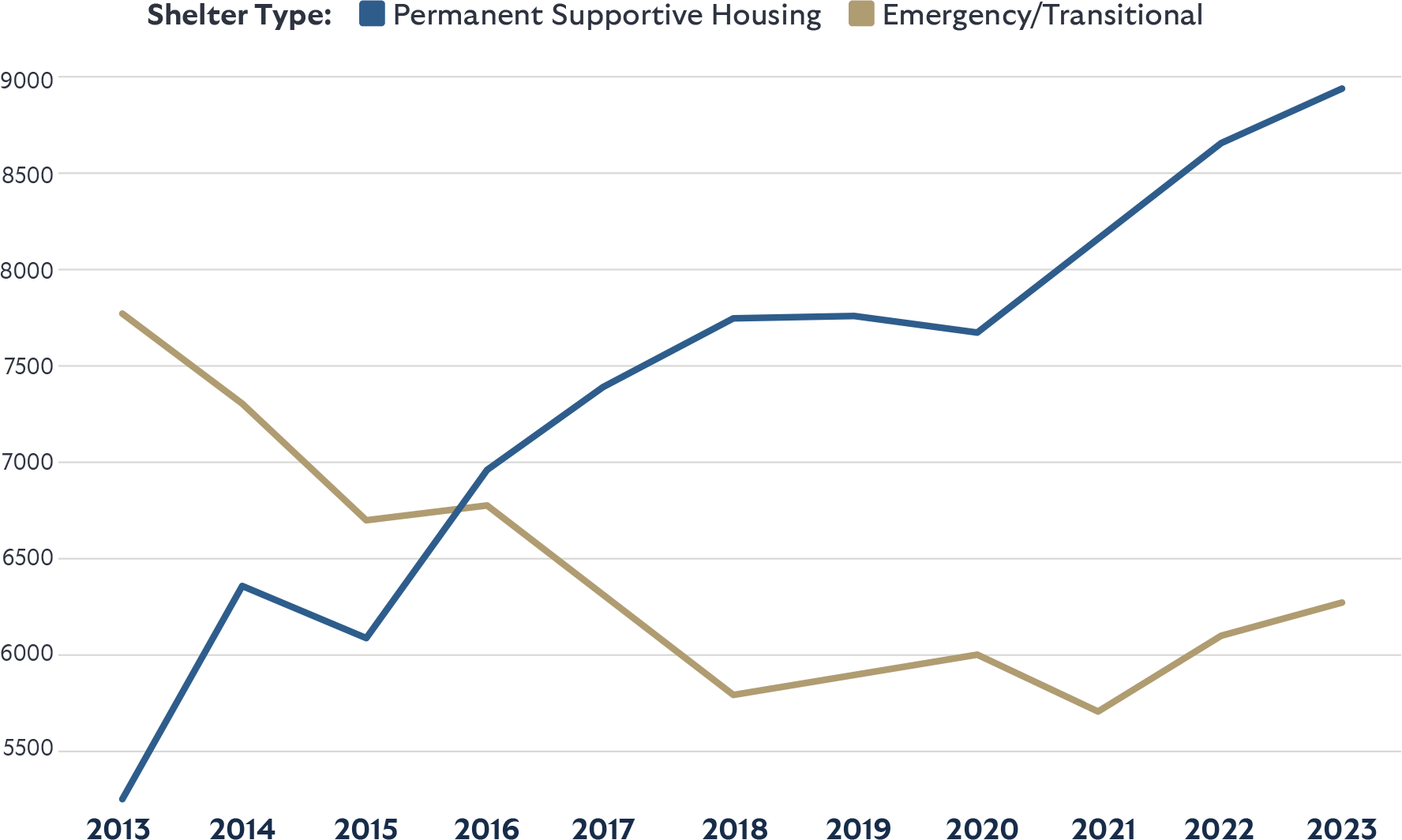

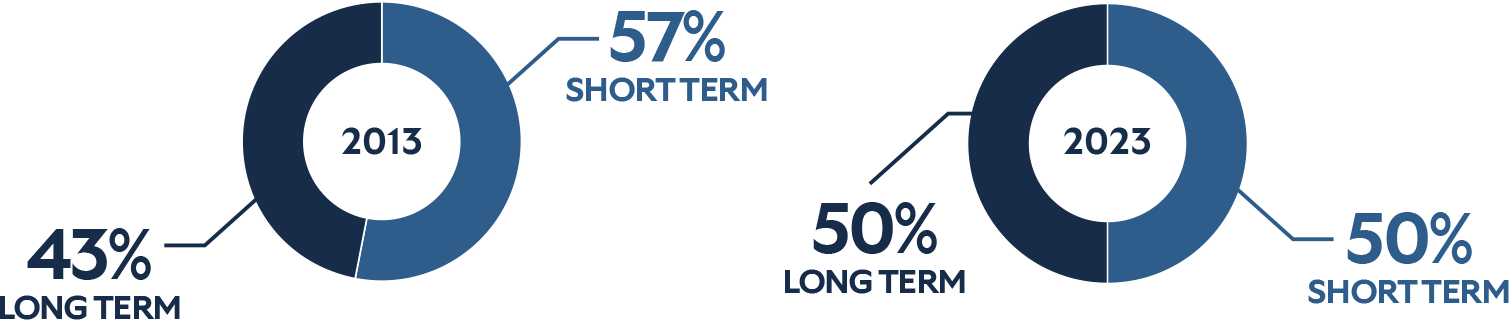

As homelessness in Missouri has grown larger and more complex, Missouri’s capacity to respond to the crisis has shifted away from short-term shelter and transitional housing and towards long-term options like permanent supportive housing. Permanent supportive housing (PSH) consists of individual, long-term apartments that do not require treatment or sobriety for tenants.6 Figure 2 shows that over the last decade, PSH increased by 71 percent, according to data from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.7 Transitional Housing (TH) and Emergency Shelters, which provide immediate assistance and beds to those living on the street, decreased by 19 percent (pictured below). Transitional homes alone decreased by 41 percent during that same time.8

These changes correlate with the growth of street homelessness. While causal studies on this topic are limited, these data offer basic insight into whether or not Missouri’s current approach to homelessness is working.

Figure 2: Missouri Housing Composition 2013–2023

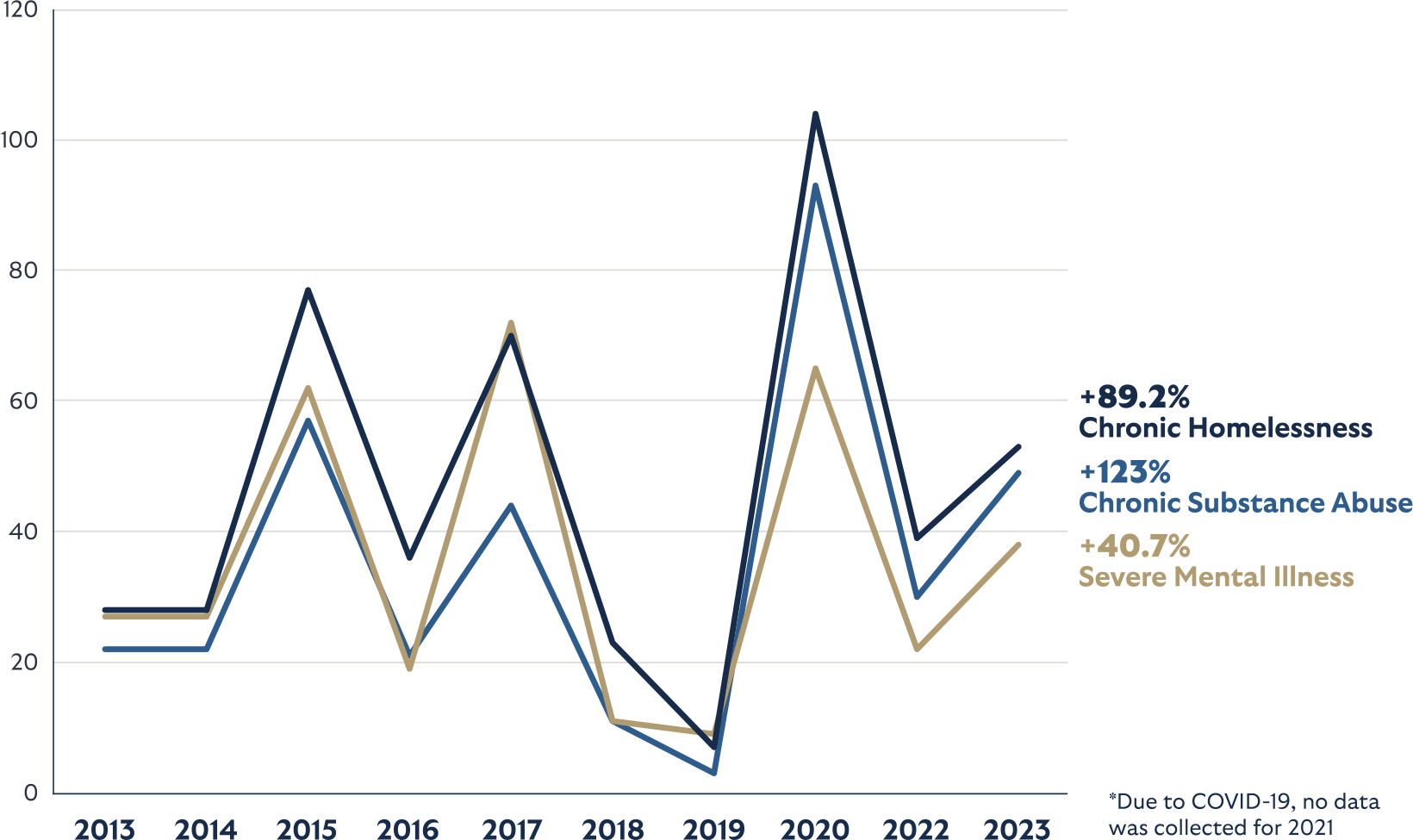

Homelessness in St. Louis

St. Louis’s homeless population has grown by about 40 percent since 2018.9 The composition of its homeless population has followed a similar trajectory as the rest of the state, though with much higher increases in severe mental illness, chronic substance abuse, and chronic homelessness, especially among the unsheltered homeless population. Figure 3 shows the trend in the number of unsheltered homeless in St. Louis that fall into each of those categories, all of which increased considerably since 2013.10 Figure 3 also includes the change in the proportion of Missouri’s response capacity that is long-term permanent supportive housing compared to short-term transitional housing.11 St. Louis is far more reliant on PSH today than in 2013.

Figure 3: St. Louis City Unsheltered Homeless 2013–2023

Long-term permanent supportive housing vs. short-term transitional housing

Additional data from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development show that homeless individuals in St. Louis with severe mental illness and/or chronic substance abuse are far more likely to be without shelter today than 10 years ago.12 The proportion of homeless people who have severe mental illness and are without shelter increased by 80 percent since 2013; for those with chronic substance abuse, the proportion more than tripled.13 Effective solutions to unsheltered homelessness must address the higher needs of these individuals.

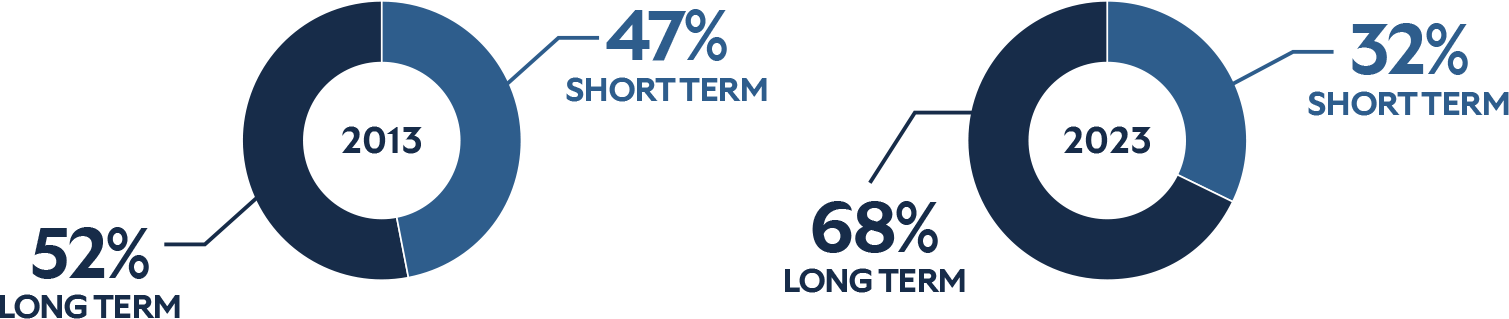

Homelessness in Kansas City

Kansas City has seen a modest increase in homelessness since 2013 and about a 20 percent increase compared to five years ago.14 The city’s statistics for unsheltered homelessness, however, are far more concerning. Since 2013, unsheltered homelessness increased 56 percent; since 2018, 168 percent.15

Figure 4 shows how the composition of the unsheltered homeless population in Kansas City has changed between 2013 and 2023 in terms of severe mental illness, chronic substance abuse, and chronic homelessness.16 Figure 4 also reveals that Kansas City followed a similar path as St. Louis and the state more broadly in scaling back the role of transitional housing in its response to homelessness.17

Figure 4: Kansas City Unsheltered Homeless 2013–2023

Long-term permanent supportive housing vs. short-term transitional housing

These numbers capture part of the problem, but additional data from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development offer more insights. Today, the likelihood of a homeless person with a severe mental illness or chronic substance abuse disorder being without shelter is 128 percent and 137 percent higher, respectively, than in 2013.18

Conclusion

Homelessness is a complex social problem that requires a multifaceted policy approach that addresses the full range and scale of the issue. Data from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development does not offer causal conclusions into the changes in Missouri’s homelessness crisis, but the trends and correlations in those data do offer policymakers and the public insight into the evolving needs of its most vulnerable population. The most effective interventions will make use of available data and target key factors with specificity.

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about our fight for policies at the state level that restore liberty through transparency and accountability in American governance.