Homelessness Diversion Programs: Mandating Treatment while Reducing Incarceration

New Solutions to Homelessness

People in the criminal justice system account for an estimated one-third of the homeless population, particularly the chronically homeless and unsheltered populations.1 In fact, formerly incarcerated people are ten times as likely to be homeless compared with members of the general public.2 Many people in this population struggle with debilitating mental illness and addiction that hinder their ability to attain and maintain housing and employment and desist from crime. Yet policymakers and non-governmental organizations typically isolate each of these factors rather than considering how they relate. Communities can address this oversight by creating criminal justice programs that divert homeless offenders of a certain risk level from jail or prison and into treatment for the underlying causes of both their criminal involvement and homelessness.

The creation or expansion of diversion programs for homeless offenders address an important gap in existing policies. Many of the NGOs that are supposed to offer services to assist the homeless have stopped requiring individuals who use their services to accept treatment for mental health or substance abuse disorders.3 This so-called ‘harm reduction’ approach appears to neglect many of underlying needs for care of the homeless population, which has, in turn, led to a recent swing of public discourse toward more assertive policies to address homelessness. Policies in this latter category include the use of the criminal justice system and involuntary civil commitment, a legal process that involuntarily compels those with significant needs for care into psychiatric treatment. Policymakers, however, have struggled to meet the public’s demands. Even where these policies have been adopted they have remained underutilized. Involuntary civil commitment continues to be used sparingly in many parts of the country, especially among homeless people.4 New solutions are in order.

One promising solution is to expand the existing and well-evidenced framework of criminal justice programs that divert individuals away from homelessness, as some jurisdictions have already done. Over the last few decades, district attorneys and judges have experimented with programs that divert people who are charged or convicted of crimes from traditional carceral sentences to alternative sanctions, like drug treatment. They have found considerable success, especially among target populations, because these alternatives address criminogenic factors. While current approaches are typically limited to mental health, substance abuse, or shelter, the diversion framework can be tailored to address the dynamic causes of homelessness. The strength of this approach is threefold:

- It creates a process by which law enforcement can compel criminally involved homeless individuals to receive treatment and other necessary services without relying solely on traditional criminal justice sanctions.

- It applies to a similar but broader set of individuals as those covered by involuntary civil commitment laws—which only applies to the most severe mental health cases—and thus has greater scope and usefulness.

- It effectively holds homeless individuals accountable for their crimes and their refusal to take advantage of mandatory treatment and services if they fail to complete the program by imposing traditional criminal justice sanctions as a last resort.

The Prison to Homelessness Pipeline

The prevalence of crime, mental health and substance abuse disorders, and incarceration among the homeless population is staggering. In Manhattan, one study found that mentally ill homeless people are 35 times more likely to commit a crime and 40 times more likely to commit violent crimes, especially toward strangers.5 The San Diego County District Attorney’s office found homeless individuals were 514 times more likely to commit a crime than the average citizen, and in 98% of cases, a homeless offender is a repeat offender.6

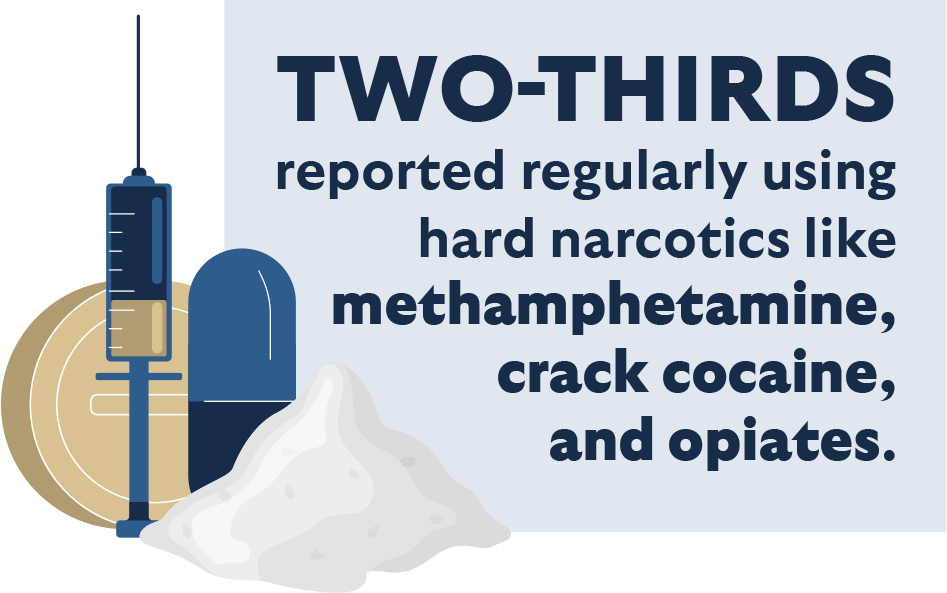

Roughly half of people in homeless shelters have been to prison, with one in five having left within the last three years.7 The University of California at San Francisco reported in June 2023 nearly one in three homeless people in California had been to prison or served a long-term jail sentence in the six months before becoming homeless.8 That same study found more than 80 percent of people experiencing homelessness reported serious mental health conditions, for which one in four had been hospitalized. Two-thirds reported regularly using hard narcotics like methamphetamine, crack cocaine, and opiates, fewer than half of which reported ever receiving treatment. A mere four percent cited high housing costs as the primary reason they became homeless.

People leaving prison have the highest risk of becoming homeless soon after release.9 Within the first two years of release, approximately 11.4 percent of those exiting prison use a homeless shelter, with the greatest portion experiencing homelessness within their first 30 days post incarceration.10 Prisons provide minimal support and transitional services to ex-inmates, and even those that do offer help have little incentive to deliver effective services and improve outcomes for their “clients.” It is no surprise, then, that more than one-quarter of the formerly incarcerated experience “a trajectory of persistent desperation and struggle, [with] frequent periods of homelessness and housing instability.”11

The Effectiveness of Diversion Programs

Diversion programs provide alternative means of accountability for certain types of offenses. Some programs are offered to criminal court judges as an optional sanction at their discretion while others create new courts with special judges focused on specific populations like veterans or drug users. Drug diversion programs treat substance abuse disorder through rehabilitation programs instead of fines or incarceration. Veterans’ courts usually focus on drug rehabilitation as well, but target veterans who develop substance use disorder from combat-related mental illnesses. The target demographic for mental health courts varies from state to state, but for many, there is no strict requirement for substance abuse disorder. Only those who commit nonviolent offenses are typically eligible.

Despite variance across counties, diversion programs can typically be distinguished by when they occur in criminal processing and what they consist of. There are police-led diversion programs that occur in place of an arrest while other programs occur pre-plea and yet others are post-plea. Less serious offenses or offenses by juveniles are often diverted earlier. Pre-and post-plea diversion programs are enacted at the discretion of the prosecutor and/or the judge (as well as agreed to by the public defender). Post-plea diversion programs require a plea of guilt under the condition that the charges will be dropped, the sentence revoked, and/or the defendant’s record expunged if the diversion program is completed. Some programs also require the defendant to pay a fee, though fee waivers are available. If defendants fail the diversion program, the case resumes or the sentence is enacted. The purposes of these programs vary between lessening the stigma of a criminal record by giving first-time offenders a second chance, reducing reliance on jails and prisons, lessening caseloads for prosecutors or probation departments, and/or rehabilitating defendants.

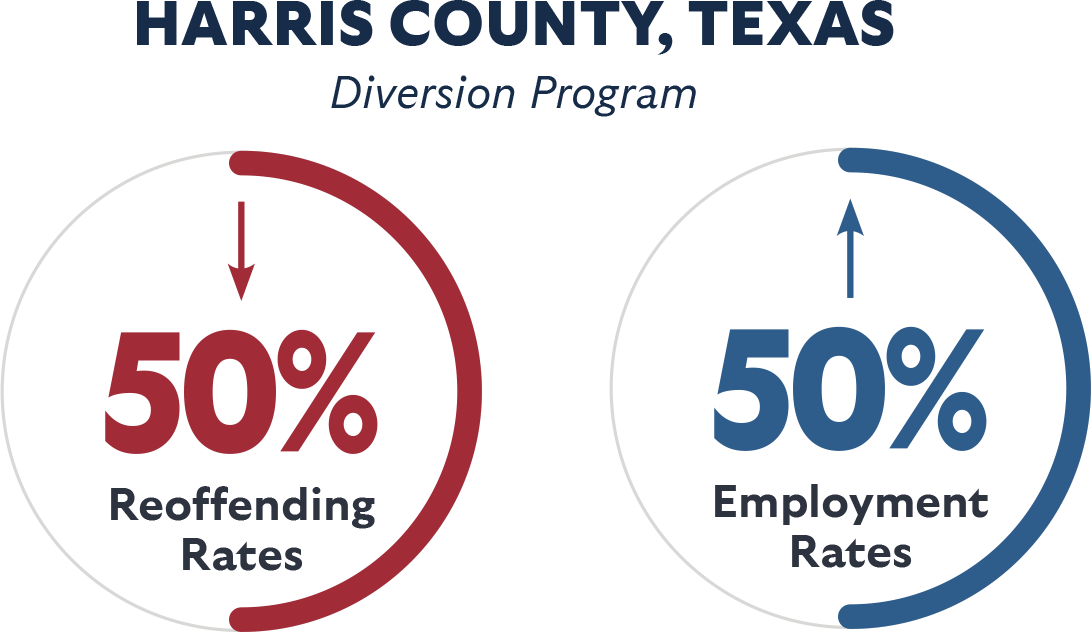

Diversion programs effectively reduce recidivism in most cases. In longitudinal studies sponsored by the National Institute of Justice, researchers found people who participated in drug courts committed new crimes at much lower rates than those in control groups, with reductions between 17-26 percent.12 The same study found the programs saved more than $6,700 in reduced reliance on public services for each successful participant. In a rigorous empirical study of diversion programs in Harris County, Texas, it was found that reoffending rates for those who completed diversion programs dropped 50 percent over 10 years, while quarterly employment rates increased by 50 percent over that same time.13 A similar study reported a drop in rearrest rates among defendants who are referred to diversion in San Francisco.14 Other studies found diversion reduces the likelihood of arrests, plea bargains, jail sentences, and convictions,i though two studies found a negligible effect on defendants with a diagnosed mental disorder or substance abuse problem.ii Though there is strong evidence to support the effectiveness of diversions though, as with all social programs, it is imperative policymakers create strong accountability mechanisms to eliminate programs that fail to achieve positive outcomes.

i. See (Johnson et al., 2020; McWhorter & LaBahn, 2016; Gill & Murphy, 2017; Cosden et al., 2003; Lamb et al.,1996; Steadman & Naples, 2005; Sung, 2001).

ii. See (Broner et al., 2004; Mire et al., 2007).

Vermont’s report on its statewide restorative justice program serves as a case study for the potential success of diversion programs with broader eligibility than substance abuse. In the case of pre-adjudication diversion, participants in the program recidivated at a rate of 20.8 percent over a period of five years, drastically lower than the national average of 79 percent. Successful completion of the entire program further decreased the rate to 18.1 percent. Furthermore, in 90 percent of these recidivism cases, the offender was only charged with a misdemeanor.15 That gives offenders who complete Vermont’s restorative justice programs a 1.8 percent chance of committing a felony within five years of release.

Outside of the rural context of Vermont, a study of eight of New York City’s diversion programs found all programs both decreased relative sanctions of those who completed the program and sanctioned those who failed the program as severely as those who did not participate.16 These two metrics indicate the New York diversion programs both properly diverted successful individuals and held accountable those who were not.

Because of their decentralized and variegated nature, as well as scarce administrative data, there is little conclusive research on the effectiveness of diversion programs in reducing crime. What is agreed upon by researchers is that diversion programs decrease overall public spending on criminal justice institutions. Reductions in cost are due to cheaper procedures along with the reduction in recidivism for those who complete programming, a high rate of completion, and a strong likelihood those who complete their programming will not relapse or commit another offense in the time monitored post-completion (usually one to five years).17

Conditions for a successful diversion program for our target population can be summarized as follows:

- The program reduces the likelihood defendants reoffend.

- In cases of reoffense, the defendant commits a less severe crime than they would otherwise.

- Effective treatment occurs that the defendant would not otherwise receive.

- The likelihood the defendant will obtain employment increases.

- The likelihood the defendant transitions into permanent housing increases.

- Traditional sanctions are maintained when the diversion program is terminated that ensures public safety and requires accountability from the defendant.

If these conditions are met, the burden on jails, prisons, and probation should decrease since frequent offenders are exiting the cycle of entry and exit.

Potential Applicability of Diversion Programs to Homelessness

The idea of implementing special diversion programs for the homeless first became policy in 1989, in San Diego.18 Since then, the American Bar Association has expressed its support for the expansion of such programs, and they now exist in one form or another in 21 different states.19 However, outside of California, and particularly in target states, these programs are limited and often do not serve major metropolitan areas most in need of such programs.

Current programs require individuals to complete an individualized improvement plan to satisfy a sentencing requirement, rather than a fine or incarceration, though they often restrict eligibility to misdemeanors, nonviolent offenses, or defendants with no prior criminal history.20 Improvement plans could include a search for employment or completion of a chemical dependency program, for instance. In addition, they are limited to the voluntary participation of individuals already connected with a shelter (where shelter advocates compose the requisite individual improvement plan) and guarantee a no custody program on principle. As it currently stands, homeless diversion courts are not accessible to individuals detained by law enforcement, only to those who seek help from shelter caseworkers.21 This puts the most vulnerable, and also the most violent, people out of reach: mentally ill, chronically homeless individuals unable or unwilling voluntarily to approach shelters or other benefit programs.

While voluntary participation in individualized improvement plans should not necessarily be eliminated as a viable alternative for homeless individuals who are able or willing to seek out such solutions, voluntary programs alone are not enough. Ideally, a homeless diversion program would include individuals already involved with law enforcement and mandate participation in residential recovery centers as a part of sentencing. When possible, a tailored path of self-improvement that encourages individual initiative, under the direct supervision of a professional, is preferable to a generalized path to mandatory residential rehabilitation. However, the limitations of voluntary programming necessitate mandatory programs that can work in tandem to serve two distinct populations with vastly different needs.

Policy Proposal: Homeless Diversion Programs

To cultivate past successes, assess the limits of current programs, and adjust them to address a high-risk population, this proposal allocates public funds to run diversion programs that provide multiple, coordinated, and required treatment services to defendants who are either transient or have unstable housing and are repeat offenders or at high risk of becoming so.

Motivation and Goals

Studies have identified a subpopulation of individuals who are repeatedly incarcerated while also frequently relying on homeless shelters, treatment centers for mental health and/or substance abuse, and public emergency services, all of which incur significant public costs.iii These individuals require multiple services simultaneously, in a coordinated fashion, and with sufficient accountability if they are to escape cycling between public agencies. The purpose of the present proposal is to enable district attorney (D.A.) offices to divert identified persons who fall within this subpopulation into multiple, coordinated rehabilitation services so they may contribute to society, improve their life outcomes, and lessen their social burden. Common diversion programs focus on veterans, mental health needs, or substance abuse treatment, often singly and without the provision of stable housing (except in cases of inpatient treatment centers or homeless courts that partner with sheltering services). As a result, these diversion offerings do not address the range of criminogenic factors affecting the target population—chronically homeless people. The proposed program remedies this lack.

iii. See (Caton et al., 2007; Culhane et al., 2010; Culhane et al., 2002; Hall et al., 2009).

Overview of Budget

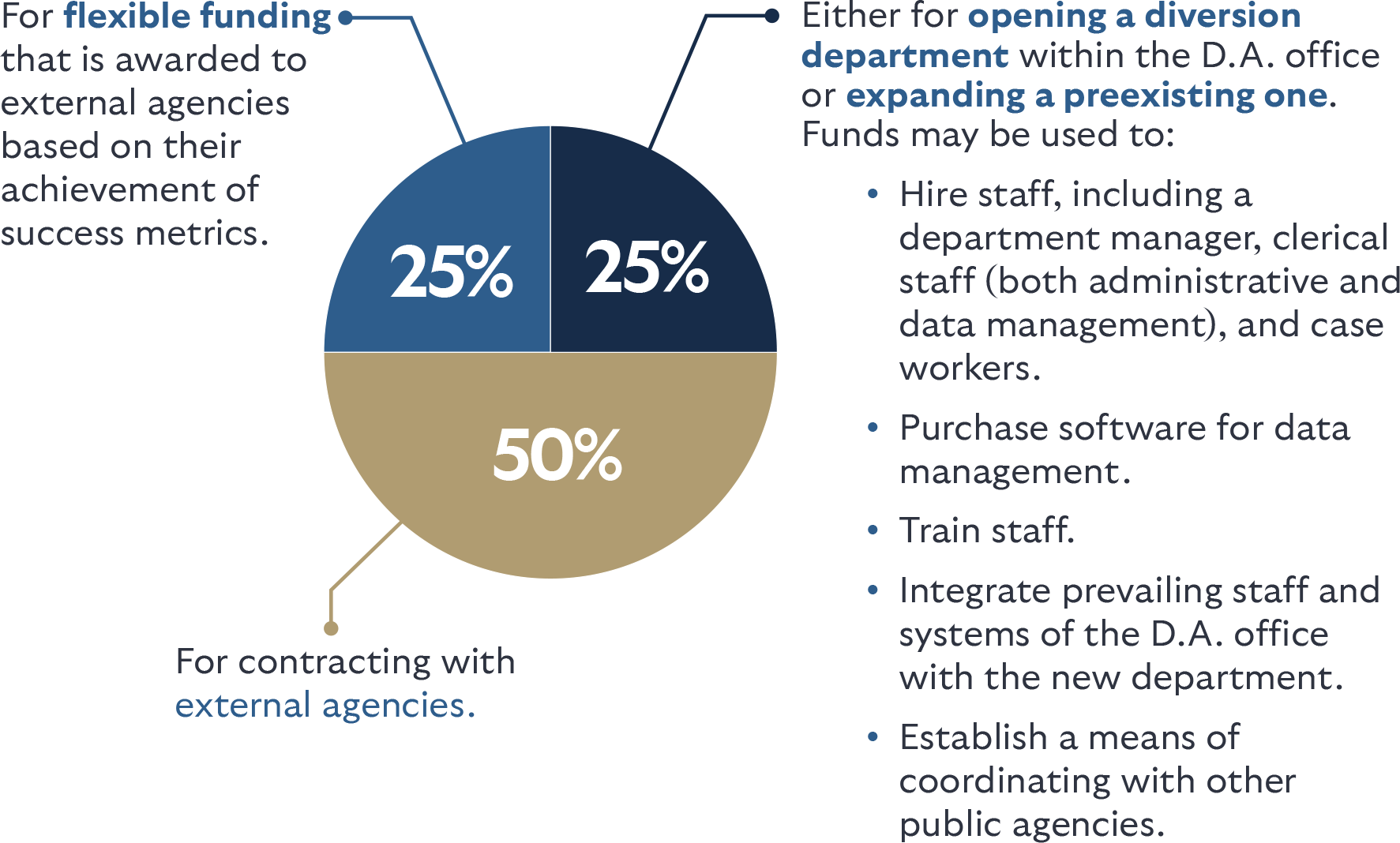

Participating D.A. offices receive funding to:

- Either open an internal department that runs the proposed program or enlarge their preexisting diversion department to accommodate this program. These funds also include developing data management contingent on current capabilities.

- Contract with external agencies that provide mental health treatment, substance abuse treatment, other health assistance, social services, employment services, and sheltering services.

- Pay for the defendants’ costs of participating in these services for the duration of the diversion program.

In addition, a state grant fund will be created to support the creation of new external agencies to deliver these services or the expansion of existing external agencies to increase capacity if participating D.A. offices lack sufficient external partners.

The budget will be allocated as follows:

Overall Responsibilities of the Coordination Department

Responsibilities fall within four categories: (1) overseeing a defendant’s participation; (2) contracting and coordinating with external agencies as well as monitoring their success; (3) data tracking and management; (4) generating cyclical reports for the district attorney and state. Under overseeing a defendant’s participation, the department identifies eligible defendants after charges have been filed, works with assistant district attorneys to offer a treatment plan, ensures the transition into a diversion program, enacts the treatment plan, reports violations of conditions for participation, ensures the traditional sentence is imposed in the event of violations, ensures the sentence is dropped and the disposition changed to “not guilty” after program completion, and establishes a post-program plan for continued treatment.

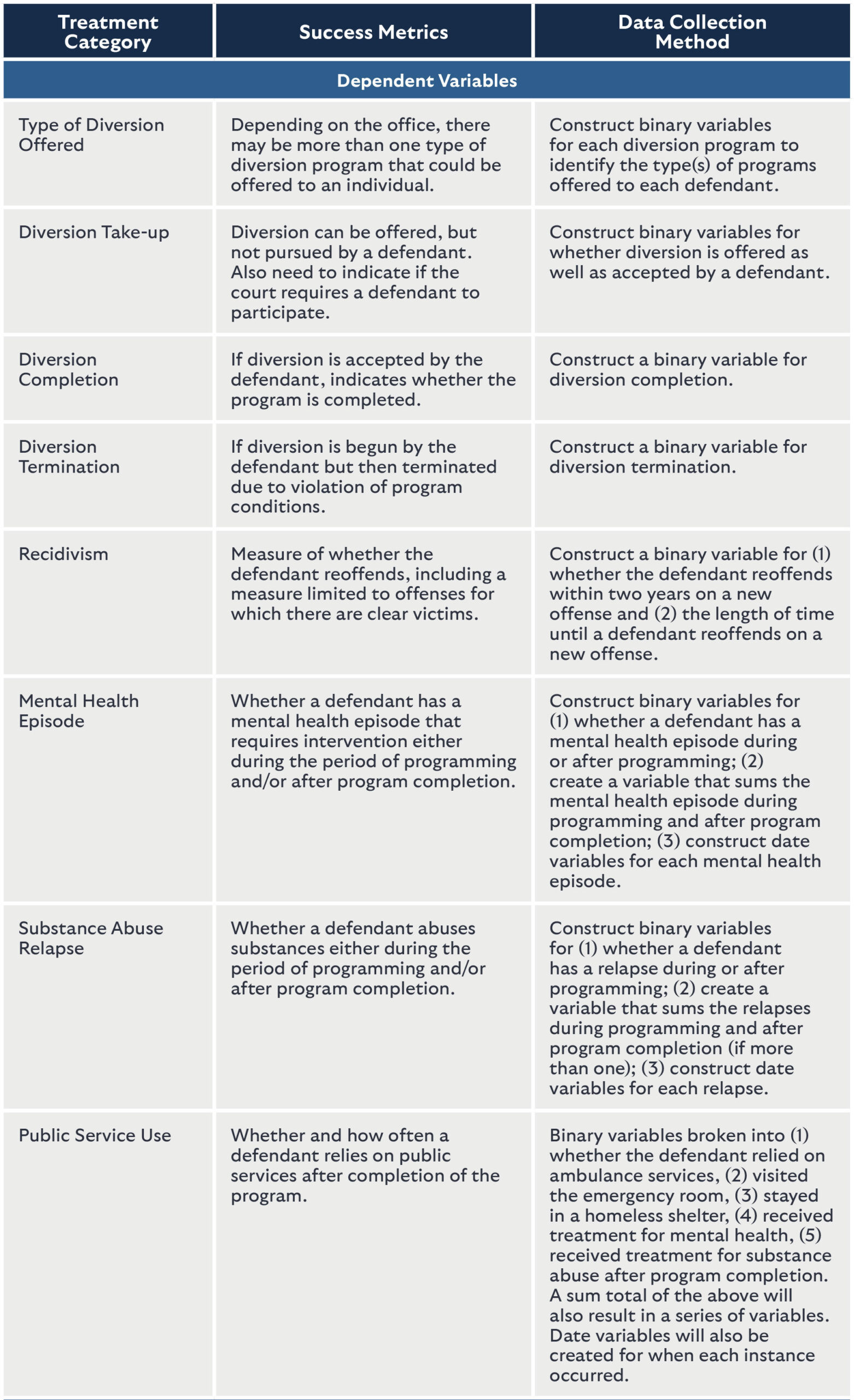

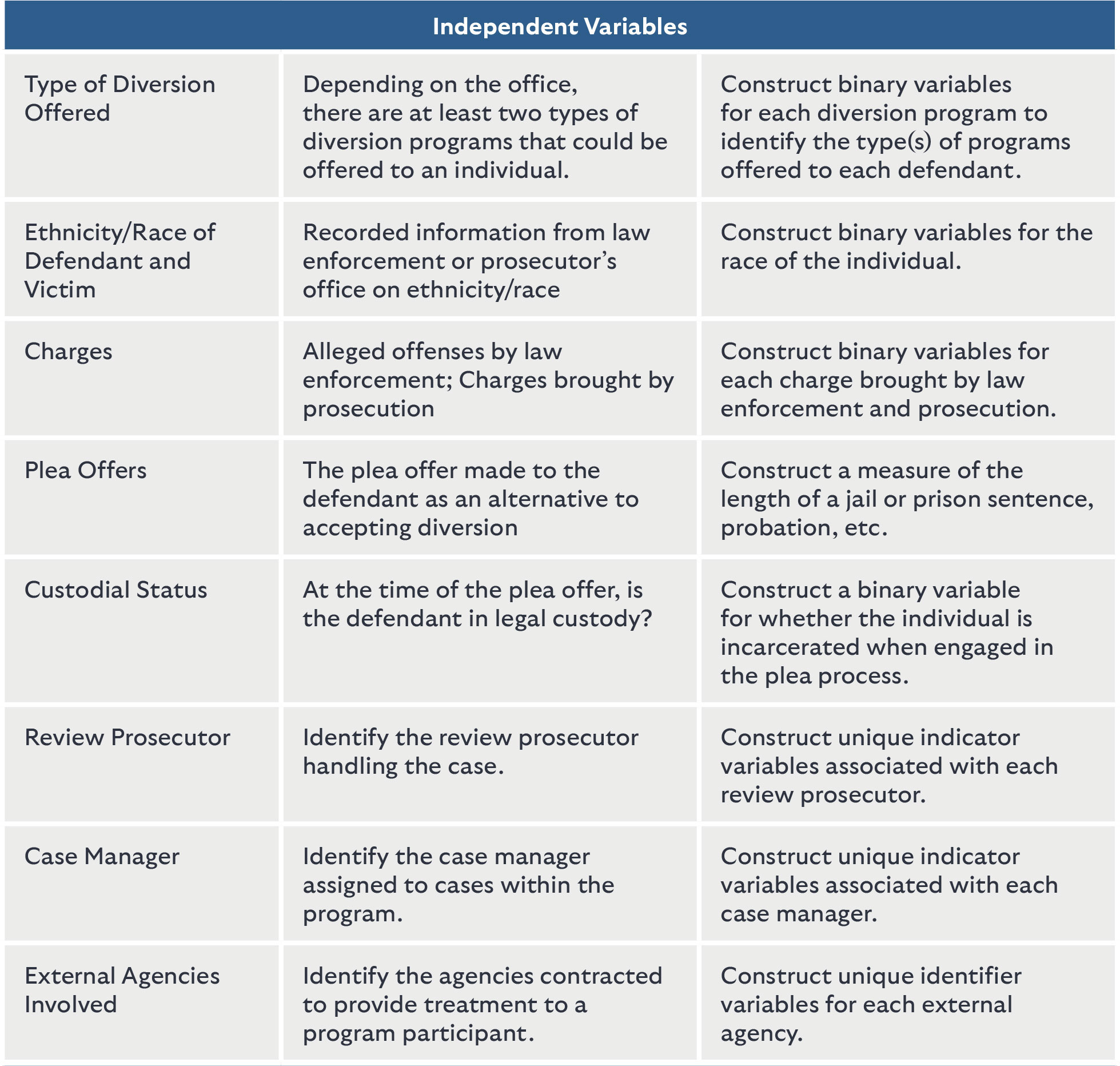

With respect to partnering with external agencies, the department vets potential agencies, negotiates contracts (requiring approval by the D.A.) that include financial incentives for successful rehabilitation, coordinates across agencies according to a treatment plan, and monitors contracted agencies. Part of its responsibility to monitor external agencies is to track data, the third category. Data collected spans defendants’ criminal history, current charges, the assistant district attorney assigned to their case, defendant characteristics, treatment plan, responsibilities of external agencies, events (such as when they receive treatments and what violations occurred, if any), post-program plan, and outcomes. A comprehensive survey will also be administered and recorded by the department upon program entry, at regular intervals, and upon program completion. A follow-up survey should be attempted six months and one year after program completion. Part of data collection, moreover, is receiving and reporting data to other agencies, such as data on the defendant’s use of other public agencies. These data must be collected and maintained to respect the participants’ right to privacy and cannot be used against the participants in court.

The final responsibility of the department is to generate reports on program operations and outcomes for the district attorney and state. These reports will be used in cyclical evaluations at both levels to ensure the program rehabilitates participants, reduces participants’ reliance on public services, and so justifies public funds.

Eligibility Criteria for Defendant Admittance

Baseline eligibility depends on evidence of transience, unstable housing, and/or stays in homeless shelters and/or treatment centers within the last six months for longer than three months cumulatively. Eligibility is determined by whether the defendant reports an address, whether they are the primary occupant of the address they provide, and the screening of defendants by the coordination department. The department will use the federal definition of homelessness to guide but not dictate its determination of eligibility for the program. One or more of the following four conditions must be met:

- An individual or family who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence, such as those living in emergency shelters, transitional housing, or places not meant for habitation.

- An individual or family who will imminently lose their primary nighttime residence (within 14 days), provided that no subsequent housing has been identified and the individual/family lacks support networks or resources needed to obtain housing.

- Unaccompanied youth under 25 years of age, or families with children and youth who qualify under other Federal statutes, such as the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act, have not had a lease or ownership interest in a housing unit in the last 60 or more days, have had two or more moves in the last 60 days, and who are likely to continue to be unstably housed because of disability or multiple barriers to employment.

- An individual or family who is fleeing or attempting to flee domestic violence, has no other residence, and lacks the resources or support networks to obtain other permanent housing.

Given the intensive nature of this program, the department must also determine that no other diversion services would adequately address the defendants’ needs. That is, there must be more than one criminogenic factor for which the likelihood of successful rehabilitation depends on various services. Except for a list of enumerated egregious offenses, the severity or type of charge against the defendant does not necessarily disqualify them from admittance, nor does their criminal history.

Deferred Adjudication

To participate in the program, the defendant must agree to a plea agreement in which the defendant pleads guilty to a relevant crime and accepts a traditional sanction for that crime if the defendant is terminated from the program.iv The judge may issue a sentence that will go into effect upon termination but the defendant will be offered the alternative sanction of participating in this program.v

iv. The possibility of resentencing deters defendants from reoffending within a given follow-up period. Besides incentivizing defendants to complete the program, deferred adjudication may also deter participants from reoffending.

v. The roughly 50 percent drop in reoffense rates and 50 percent increase in employment found by Mueller-Smith and Schepel (2021)—the most promising causal estimate currently in the literature—examined a diversion program that operated with deferred adjudication. Note, however, that the aim of diversion in their study was reducing first-time offenders’ criminal records, not rehabilitation; in fact, diverted cases were handled identically to those on probation.

Data Coordination for Entry

Program success is facilitated by data sharing agreements between public agencies as information pertaining to a defendants’ hospital stays, shelter stays, mental health and/or substance abuse treatment enables the coordination department to identify eligible defendants and align treatment plans with prior care. The department should establish sharing agreements that protect defendants’ rights to privacy.

Participant Survey

Upon program entry, participants must complete a comprehensive survey that covers demographics, current living arrangements, residential history, health conditions and history (including mental and behavioral health), alcohol and substance use, substance abuse services, social networks, and the need for social services. Baseline questions, their categorization, and justification are provided below. The purpose of these surveys is to identify predictors for completion as well as check the adequacy of the match between defendants and the program.

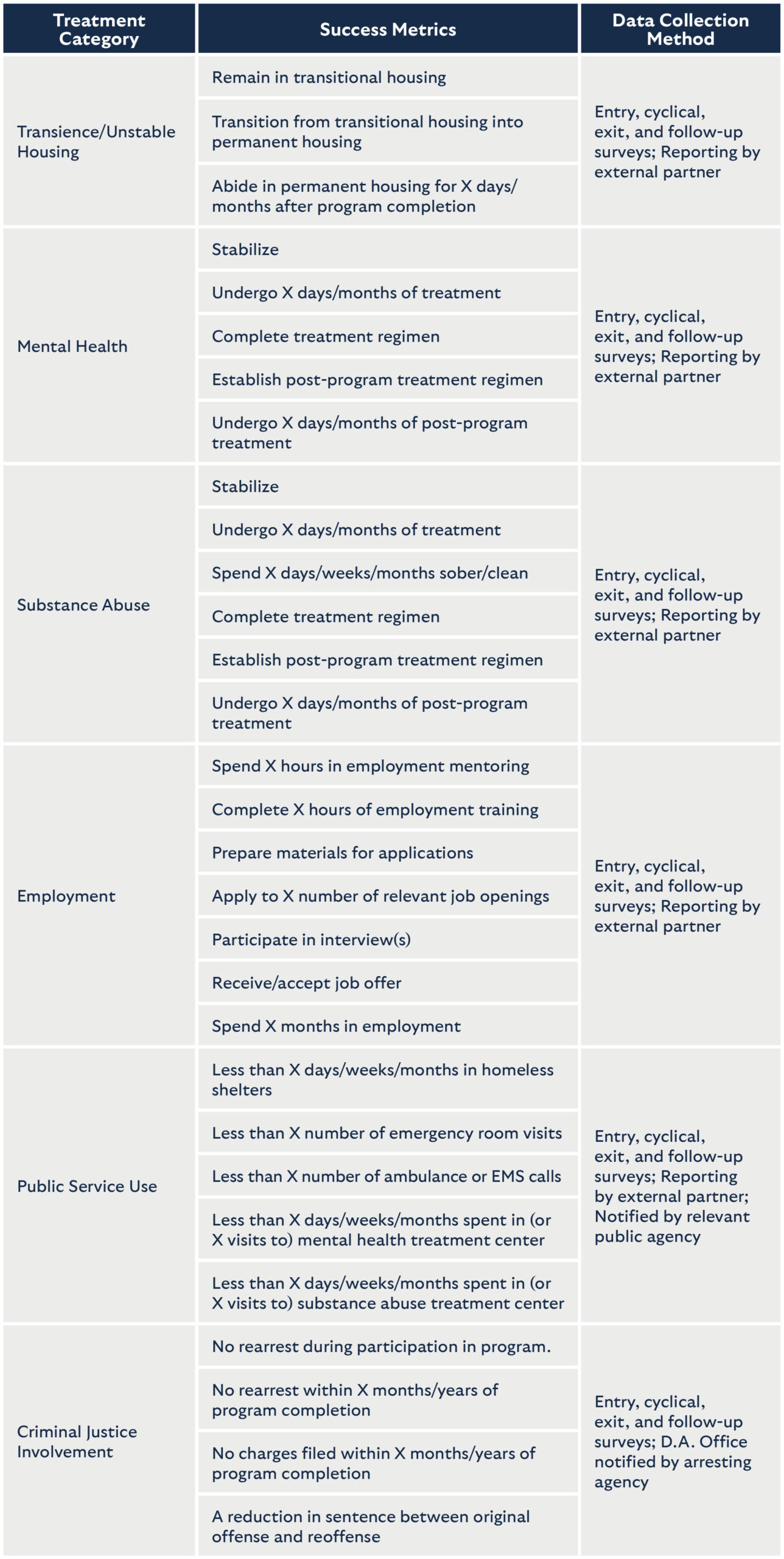

Definition of Treatment Plan and Success Metrics

The D.A.’s office defines the terms of the treatment plan and metrics for program completion, which is then offered to the public defender and their client and ultimately approved by a judge who offers the program in lieu of a traditional sentence. The treatment plan has five categories of which more than one category applies to a defendant (part of the eligibility criteria above).

- Transience or unstable housing

- Mental health

- Substance abuse

- Lack of employment

- Public service use

Success metrics are likewise attached to each treatment category.

Violation of Terms for Participation

If a defendant violates the terms of program participation, the public defender and prosecution are notified, and a hearing is set before a judge. Both the public defender and prosecution are able to recommend either the defendant’s termination from the program or continuance in the program, perhaps renegotiating the treatment plan and its terms. If the defendant commits a new crime during the program, the defendant is presumed to be terminated from the program unless the elected prosecutor—and not a designee—directly overrides the presumed termination. If a defendant is terminated from the program, the prosecution proceeds with the plea agreement’s traditional sanction.

Eligibility for External Agency Contracts

Partnerships are contracted at the discretion of the coordination department and D.A. However, evidence must be on hand of the competency of the external agency—or in the case of a start-up, of the external agency’s leadership. This evidence may span the following:

- History of successful program completion and relevant outcomes

- Agency’s available resources for carrying out treatment and data reporting

- Staff histories, education, and/or certifications

- Testimonials from past/current clients

Besides baseline eligibility, the contract must include conditions under which the contract will be void. For example, abuse or neglect of clients related to the agency’s responsibilities; lack of cooperation with the D.A.’s office, and/or other external agencies; and/or persistent negative results during treatment of a client or after program completion.

Coordinating Services for Completion of Treatment Plan

When a defendant has been admitted into the program, the primary responsibility of the coordinating agency is to facilitate needed treatment services to ensure the most benefit for the client in the most efficient manner possible. Since the program’s implementation depends on an individualized treatment plan, the department’s success in achieving these goals requires discretion on a case-by-case basis. There must likewise be a degree of flexibility in the treatment plan. For example, if the treatment plan initially requires mental health services that turn out to be irrelevant to the defendant’s needs, the treatment plan should be revised accordingly.

Accountability for External Agencies

Contractually, external agencies must provide frequent reports to the coordination department on the status of their clients. This data sharing enables the department to monitor the agency’s completion rates and outcomes. Every year, the agency will receive a brief report containing respective trends and, if needed, a meeting should be scheduled to review trends, decide on changes, and renegotiate or terminate the contract. These trends will be used in determining additional payments to the agency (see incentive schedule below).

Participation of District Attorneys Offices

District attorney offices are able to opt in to this program in most cases. If the jurisdiction had a homeless population above the per capita statewide average for comparable jurisdictions in any of the immediately preceding two statewide counts of the homeless population in the state, participation in the program is mandatory.

Cyclical Evaluation

Every year, the department will report to the D.A., who will then report to the state. The D.A. will ensure the program is producing beneficial, efficient results and will make changes or recommendations when needed. The report to the state will ensure the same. The reports received by the state will be collated and used to:

- Determine whether budgetary adjustments are needed every three years.

- Decide whether to renew the program.

The data generated will be sent to an external and neutral data science agency that will measure the effects of this program as well as conduct a cost-benefit analysis. These analyses will be run on specific offices. To be renewed, it must be shown that the program exhibits benefits overall to participants and public institutions and that the costs do not excessively outweigh the benefits gained.

Continued Care After Program Completion

Funds are set aside to defray the costs of continued services after program completion. These funds do not cover the entire costs of continued care but cover 75 percent of services for the month after completion; 50 percent for the second month after completion; and 25 percent for the third month after completion until the responsibility of care returns to the individual who completed the program and their insurance. Financial support for continued care ceases if the individual is rearrested.

Conclusion

As cities and states across the country face worsening crises of public safety and homelessness, policymakers need a greater array of tools to address problems in a diverse population. While the vast majority of people who experience homelessness only do so temporarily or episodically, a small number remain chronically homeless and often unsheltered.22 Studies find consistently that this population interacts most frequently with the criminal justice system, emergency medical services, and other public services with limited coordination among providers.

Homeless diversion programs offer a balanced approach to providing services to criminally involved individuals living on the street and prioritizes treatment while ensuring accountability for both individual participants and service providers. As a result, more people experiencing homelessness who are in need will receive mental health or substance abuse treatment, fewer individuals will have to be incarcerated for presenting a continued threat to public safety, and more people will successfully exit homelessness to a place of relative stability.

Appendix: Success Metrics and Data Collection

Sample Format for Housing and Services Delivery Model

Sample Treatment Plan & Success Metrics

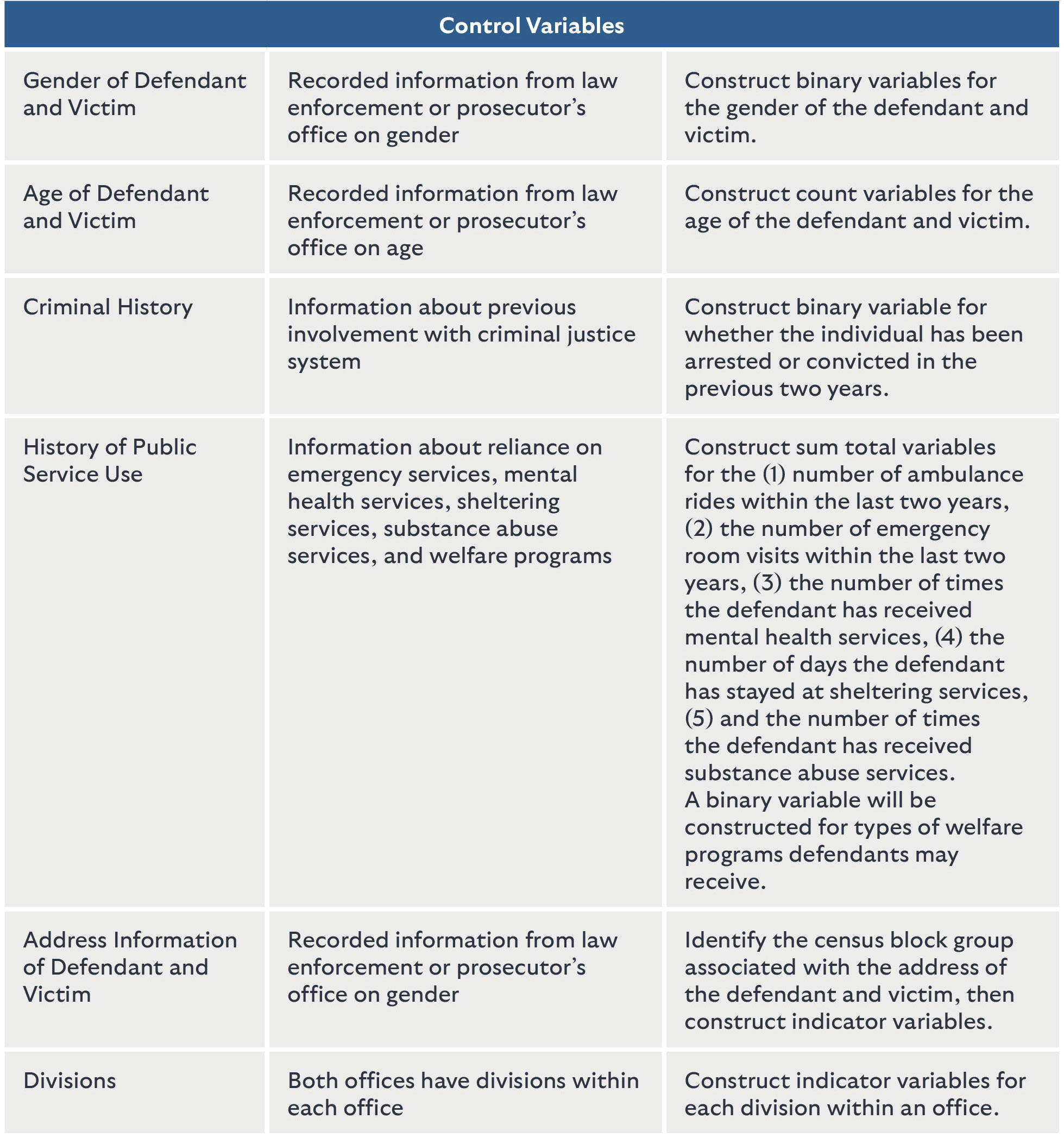

Sample Data Required from a Participating D.A.’s Office

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about our fight for policies at the state level that restore liberty through transparency and accountability in American governance.