Global Variations in Medical Residency Training

Comparisons Among Domestic Residency Programs and Between U.S. and International Programs

Introduction

Critics of issuing U.S. medical licenses to internationally-licensed physicians who received their medical training in another country often point out that training abroad differs from training in the United States. These differences, opponents argue, might leave internationally-licensed doctors unprepared to serve patients in America.

This paper evaluates the differences and similarities between residency training programs

in the United States and abroad and reaches two main findings:

- U.S. state-based residency programs for the same specialties do not look identical to one another and, in some cases, exhibit wide variation in focus and length, even at different programs located in the same state.

- Residency training in the United Kingdom and India in family medicine and pediatrics covers nearly the same topics as domestic residency training programs.

Despite differences across the U.S, states will license anyone trained in the United States. And notwithstanding these similarities, most states still refuse to recognize international training even though they will treat equally varied training from a different state as similar to the local training offered by residency programs in their own state.

Depending on where a doctor trains, he or she may have shortcomings vis-à-vis the unique practice that exists in a particular place where she or he hopes to work. But healthcare facilities across the country have, for decades, absorbed new doctors with different training and assimilated them into the local practice. If doctors trained outside the United States have similar variation, but also have significant overlap, the U.S. medical system should likewise be able to provide any necessary supplemental training and absorb internationally-licensed doctors with years of experience into the local practice customs.

Background

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) is the key institution regulating postgraduate education standards across most medical and surgical specialties. Residency ACGME accreditation mandates particular program requirements for each specialty.1 Within those requirements, programs must ensure trainees complete a certain number of clinical rotations and meet clinical, practical, and professional standards set by the ACGME.

Despite this standard setting, postgraduate residency and fellowship training varies greatly with geographic location and point in time within the U.S.2–3 Programs are situated in academic and community settings, with corresponding differences in rotations, faculty, expertise, and curricular opportunities.4 Each program must meet the ACGME mandatory minimum rotation time while maximizing the opportunities for personalized curricula development and trainee satisfaction. Variances in board pass rates also reflect the differences in program quality, experience, and culture.5

Methodology

Family Medicine and Pediatric residency training requirements were reviewed for the United States, the United Kingdom, and India. This analysis tests the variation in residency training between different countries and domestically across the United States. For the United States, the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requirements and the specific rotations of four U.S. based residency programs (Mayo Clinic and University of California San Francisco for Family Medicine; Seattle Children’s and University of Texas San Antonio for Pediatrics) were reviewed. Each was then compared the ACGME program requirements and compared with the UK General Practitioner Training Guidelines and the MD in Family Medicine and MD in Pediatrics training programs in India.

Family medicine and pediatrics are two specialties that represent significant proportions of the projected physician shortage.6,7,8 As such, this analysis focuses on these two programs to test the variation in residency training between countries and domestically across the United States.

Findings

Variation Within U.S.-based Residency Training Programs

Family Medicine

When comparing the rotations of family medicine residencies at Mayo Clinic, and University of California San Francisco (UCSF), the overlap in time spent in specific settings becomes obvious.9–10 Despite the similarities that contribute to meeting the ACGME requirements for family medicine, there are several rotations that are not shared, as well as 20 weeks of trainee-selected elective rotations at the Mayo Clinic, compared with 18 weeks of elective time at UCSF.

Figure 1. Clinical Rotations in Family Medicine from Mayo Clinic and UCSF

While it is important that family medicine doctors receive broad training across the many specialist and inpatient settings mandated by the ACGME, the cumulative time spent in each of these placements by any one trainee is relatively short. One setting that illustrates this is the emergency department, where the ACGME requires that family medicine trainees complete at least one month in an emergency department during their training.

In rural areas where there are emergency physician “deserts,” Family Medicine physicians are an important source of emergency room doctors.11 Trainees from the Mayo Clinic receive a cumulative 10 weeks of emergency medicine rotations during their residency UCSF trainees, by contrast, only complete a six-week emergency medicine rotation in their first year of residency. Despite obvious differences in patient demographics, presentations, working facilities, and time spent in emergency rooms, trainees from both institutions would be equally qualified to provide care in urgent and emergency care nationwide.

Pediatrics

A comparison across the pediatric rotations at Seattle Children’s and the University of Texas San Antonio (UTSA) presents a similar story.12–13 Over a three-year residency, pediatric trainees at Seattle Children’s are given a cumulative 36 elective weeks to rotate through a selection of over 38 subspecialties. By contrast, trainees at UTSA are allocated 28 weeks to rotate through a selection of roughly 25 subspecialties.

Board-certified pediatricians typically assume a pediatric primary care, hospitalist, or urgent care role without pursuing subspecialty fellowship training. While the ACGME requires a minimum of two community outpatient blocks during pediatrics residency, Seattle Children’s has three blocks, while UTSA allocates five blocks for their trainees.14 Additionally, two of the three blocks for Seattle Children’s are community practices in Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho. It is clear that a pediatrician trained at one institution will not have an identical experience base to pediatricians from other institutions nationwide. And yet a physician trained in pediatrics at UTSA can obtain a license in Washington state or any other state in the United States despite these variations.

Figure 2. Clinical Rotations in Pediatrics from Seattle Children’s and the University of Texas San Antonio

Variation Between U.S.- and Foreign-Based Residency Training

The goal of medical training is universally shared: to train competent, independent, and safe medical practitioners. The features of postgraduate residency training in many specialties have been studied and compared between the U.S. and many different countries (e.g., emergency medicine, radiology, general surgery, public health and preventative medicine, anesthesiology, ophthalmology, infectious diseases).15,16,17,18,19,20,21 These investigations demonstrate many similarities in training regimes across countries, as well as highlighting some of the differences that are also present between American training programs (e.g., program size, call times, etc.).

Postgraduate training standards for pediatrics and family medicine were investigated in India and the United Kingdom, two countries with large proportions of doctors eager to move to the U.S.22 It is worth noting that graduate doctors in these countries must first work for up to three years before entering specialty training. Family medicine training in the UK and India takes three years, like in the U.S. For pediatrics, specialty training takes seven years in the UK and three years in India. Freshly qualified specialty doctors in these countries have, therefore, been practicing for longer than their American counterparts. Beyond bringing a wealth of medical expertise, they also could bring a global perspective to American healthcare.

Family Medicine

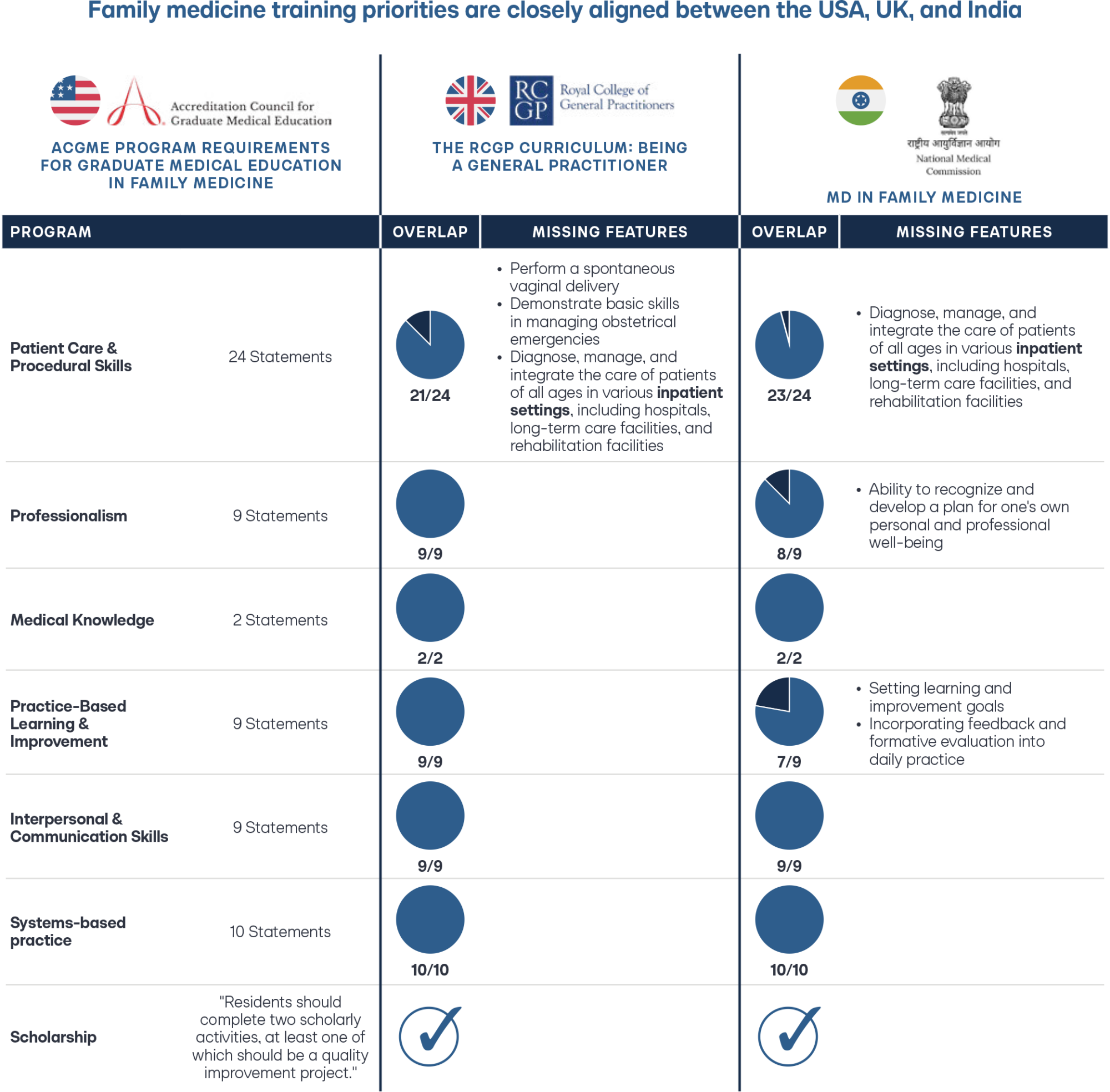

In family medicine, the ACGME family medicine residency requirements make 63 statements outlining competencies related to patient care, procedural skills, professionalism, medical knowledge, practice-based learning, interpersonal and communication skills, and systems-based practice.23 The UK General Practitioner Training Guidelines highlight 60 of the same competencies within their own training requirements documentation.24 Similarly, the MD in family medicine requirements from India make reference to 59 of the same competencies outlined by the ACGME.25 While specific rotations and experiences might vary, an American-trained board-certified family medicine doctor may hold a remarkably similar knowledge base and practice values to a family medicine doctor from the UK or India.

Figure 3. Family Medicine Program Requirements Across Domains in the U.S., UK, and India

Pediatrics

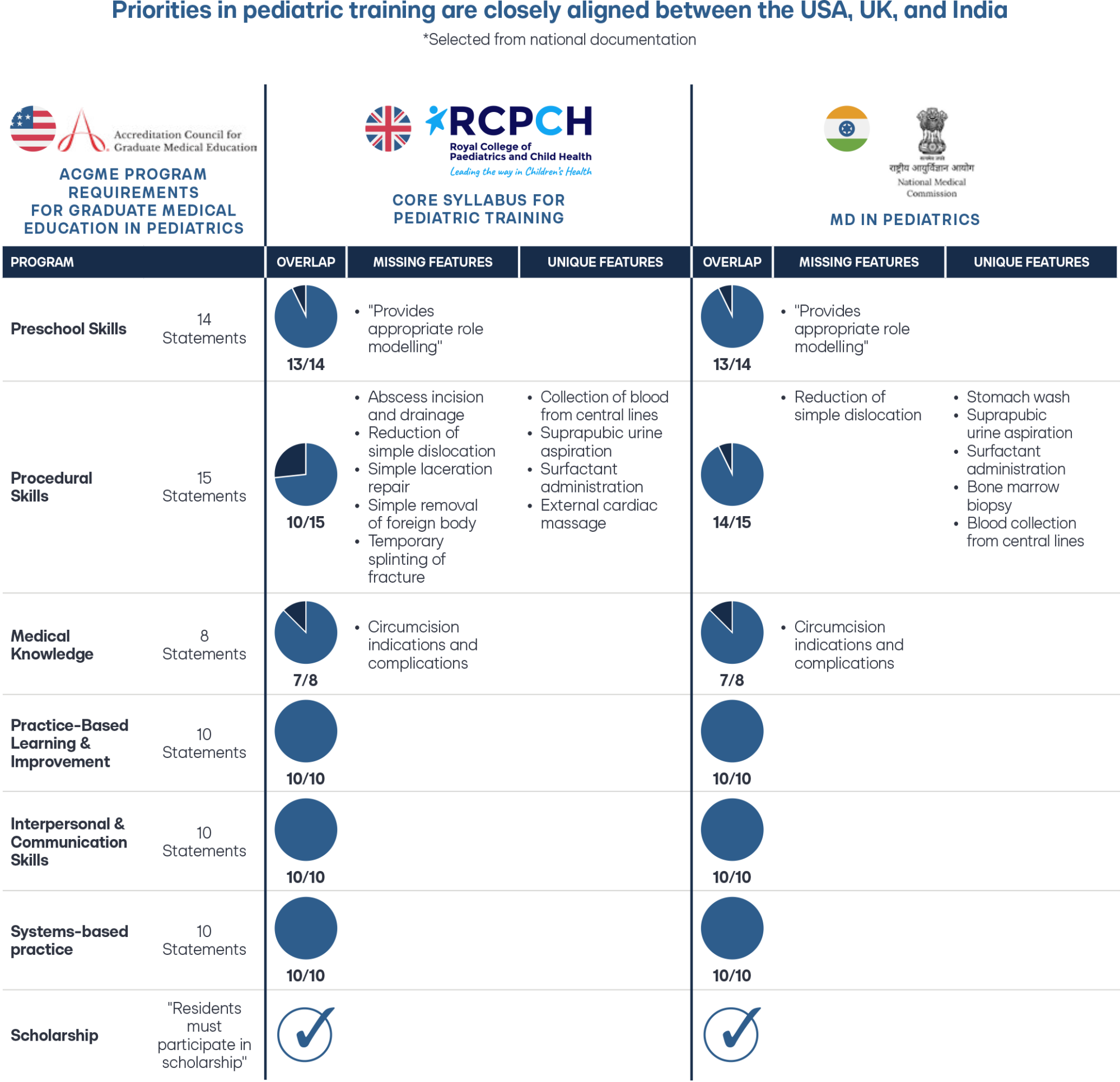

In pediatrics, the ACGME made 67 statements across similar domains to family medicine, which compliant programs must meet for their residents to gain competencies and become eligible for their pediatric board exams. The UK Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health Training Guide has similar statements outlining their training requirements and overlaps with 60 of the ACGME statements.26 The MD in pediatrics training program from India also has a set of statements that overlapped with 64 of the statements made by the ACGME.

Figure 4. Pediatrics Program Requirements Across Domains in the U.S., UK, and India

When comparing procedural skills training requirements for Pediatric residents in India against the U.S., residency training in India requires competency in 14 of the 15 procedural skills set out by the ACGME in the U.S. At the same time, the UK highlights 10 out of 15.27–28 Several procedures explicitly required in the Indian and UK programs are excluded from the American requirements, such as performing a bone marrow biopsy and suprapubic aspiration. It is entirely plausible that pediatric specialists from India and the UK can perform the missing procedures, such as reducing a simple dislocation, a very common presentation in pediatric emergency rooms. Still, their guidelines may not have explicitly specified this capability.

Conclusion

International doctors with years of experience who completed their postgraduate training abroad could bring a wealth of experience, knowledge, and practice to patient care in the U.S. This robust training and ability would be an asset to physician and patient communities. There is no perfect overlap between training programs in different countries; patient population, cultural norms, and local guidelines will all vary to some degree between different countries, just as they differ from one state to the next domestically. This is why it is most sensible to find a balance between avoiding a complete repetition of clinical training and recognizing the value of foreign postgraduate training and experience of an individual capable of passing an American Board Licensing exam.

States continue to create pathways that enable internationally-licensed doctors a provisional license to practice in the United States when sponsored by a healthcare provider in that state. And hospitals, Federally Qualified Health Centers, and other healthcare facilities are beginning to hire these doctors.

In the months and years ahead, we will better understand the unique needs for supplemental training and the best methods to provide such supplemental training for these experienced internationally-licensed doctors as they progress along the pathway from provisional license to full and unrestricted license, all the while providing care to fill the gaps in America’s physician shortages.

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about our fight for policies at the state level that restore liberty through transparency and accountability in American governance.