Drug-Free Homeless Service Zones

Overview

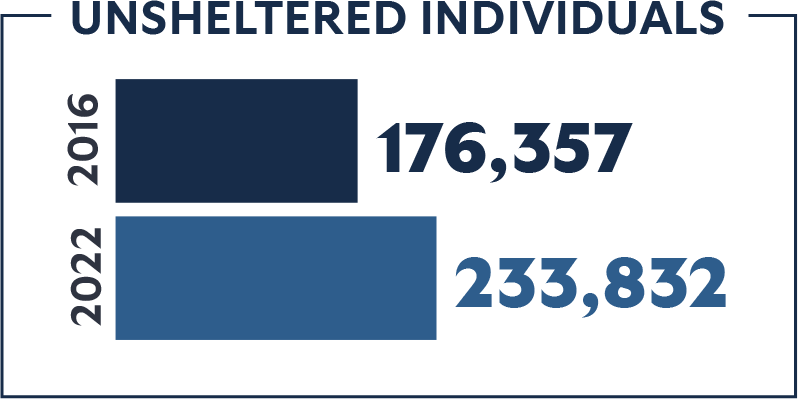

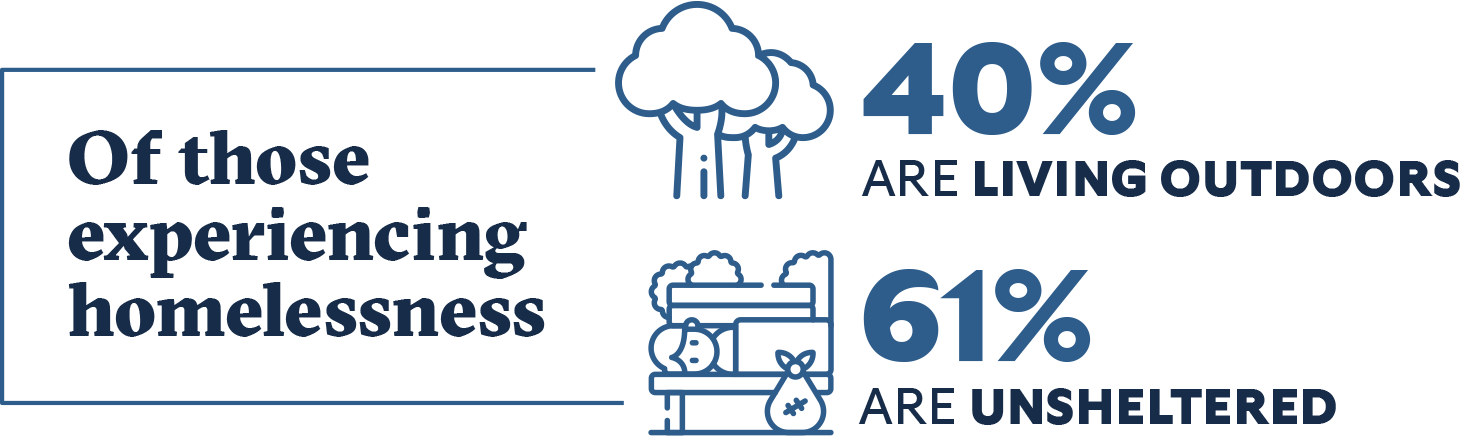

A record number of Americans are experiencing unsheltered homelessness. According to data from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the number of unsheltered individuals increased from 176,357 in 2016 to 233,832 in 2022.1 An estimated 40 percent of those experiencing homelessness are living outdoors and 61 percent of the chronically homeless are unsheltered.2

As the number of people living on the streets of America’s cities has grown, public safety has suffered for both homeless people and the communities in which they live. A recent poll by the Cicero Institute found that 66 percent of Arizonans feel unsafe due to homeless encampments on city streets.3 Much of this problem can be attributed to the connection between homelessness, drug use, and other crimes fostered by the illegal drug market.

As part of their response to homelessness, policymakers should make a concerted effort to intervene in the drug market that preys on vulnerable people experiencing homelessness and perpetuates their destitution. One solution with a proven record of success is to create drug-free zones. Historically, drug-free zones have been used successfully to curb drug dealing in and near schools, and a similar model could be applied to areas in which homeless people seek safety, shelter, and services. While drug-free zones do not effectively target the illegal drug market generally, they are effective at deterring drug-related crime in specific areas frequented by vulnerable populations.

Prevalence of Drug Use Among Homeless People

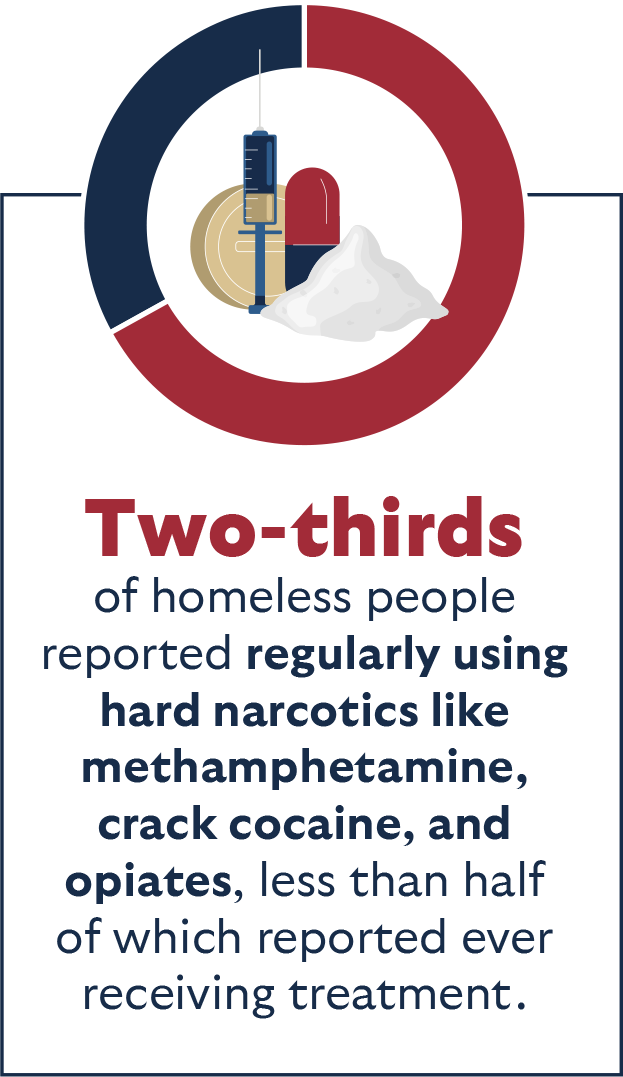

Chronic substance abuse has decreased among homeless people across the United States, but increased in prevalence among unsheltered homeless people specifically—the fastest-growing and most vulnerable portion of the homeless population. Since 2013, the number of unsheltered homeless people who use drugs chronically has grown by 30 percent.4 The largest study of homelessness in America in 2023 found that two-thirds of homeless people reported regularly using hard narcotics like methamphetamine, crack cocaine, and opiates, less than half of whom reported ever receiving treatment.5 Certain states have seen even more dramatic growth. Arizona’s total homeless population saw a 170 percent growth in substance abuse since 2012, including 560 percent growth among the unsheltered homeless and 37 percent growth among sheltered homeless.6

The growth in mental illness among homeless individuals has similar trends to that of drug use. A University of California at San Francisco study found that more than 80 percent of people experiencing homelessness reported mental health conditions, for which one in four had been hospitalized.7 Over the last decade, the number of homeless people suffering from severe mental illness rose by 16 percent, with a disproportionate impact on unsheltered homeless people which rose 38.5 percent.8 Many states saw much larger increases than national statistics convey. This high rate of mental illness puts the homeless population at an especially high risk of developing substance abuse disorders or relapsing because people with poor mental health are especially susceptible to drug use. They have been shown to have much higher rates of all types of substance abuse than the general population.9 An estimated one in four people with severe mental illness have a substance use disorder, and 49 percent report using drugs.10

As the homeless population in America rapidly increases, and drug use increases among this group, rates and risk of substance abuse have both become debilitatingly high. Policies that aim to protect, support, and assist homeless individuals cannot ignore the problems posed by the predatory illegal drug market that further harms a struggling cohort of people.

Public Safety Concerns

High rates of substance abuse and mental illness create an environment in which people are both more likely to be victims of crime and to commit crimes themselves, and the ensuing disorder further attracts opportunistic criminals. This is precisely the problem faced by people experiencing homelessness and the communities in which they live.

In 2022, roughly one in four homicides and 15 percent of all violent crimes in Los Angeles involved homeless individuals as either perpetrators or victims, or both, despite representing less than one percent of the population.11 The San Diego County District Attorney’s office found homeless individuals were 514 times more likely to commit a crime than the average citizen and, in 98 percent of cases, a homeless offender is a repeat offender.12 The University of California at San Francisco found in a June 2023 report that nearly one in three homeless people in California had been in prison or a long-term jail stay in the six months prior to becoming homeless.13

The public disorder associated with homelessness sometimes follows individuals from the street into areas where they receive shelter, services, and other support. Moving people off the street and into shelters is an effective way to reduce public camping—which is the riskiest mode of homelessness in terms of both public health and public safety—and some of the crimes associated with it.14 But there is much that needs to be done to ensure a safe transition from the street into a more stable environment. A study from the RAND Corporation and the University of Pennsylvania found homeless shelters increased property crime by 56 percent within 100 meters of the shelter while reducing criminal trespass by 34 percent.15 The study also found the impact on crime was limited to the vicinity of the shelter, with effects dissipating over two to three blocks of the shelter. Another report on permanent supportive housing for homeless people found that both total crime and violent crime increased within 500 feet of permanent supportive housing units, with a greater effect in the vicinity of large facilities.16

These findings are consistent with larger reviews of available studies that found permanent supportive housing does not reduce criminal activity among people who are homeless.17 Moreover, there is substantial evidence that permanent supportive housing has no discernable positive impact on illicit drug outcomes for homeless people.18-19 Given the high rates of crime and drug use involving people who are homeless, shelters and other housing and support services must do more to improve these outcomes if they are going to be successful in upholding order in their facilities and public safety in their vicinity.

Policy Proposal: Drug-Free Homeless Service Zones

Drugs exacerbate the challenges facing the homeless by exposing them to criminal predation, attracting criminal activity and disorder that further destabilizes their environment and enables criminal behavior among them. Drug dealers who target homeless people take advantage of their vulnerability due to extreme economic distress and serious mental health conditions, eroding public safety. It is imperative that policymakers curb the prevalence of illegal drug markets near areas that serve the homeless so struggling individuals can have a chance at success.

Throughout the 1980s, all 50 states created drug-free zones to counteract the encroachment of drug dealing and use into concentrated areas of children such as those near schools, daycares, and school bus stops. Many states required these areas to have signs that read “drug-free zone,” warning of enhanced punishments if the signs were ignored. Studies of these policies found evidence of the effectiveness of drug-free school zones in significantly reducing drug crimes near schools.20 Other studies note the primary limiting factor of these policies is keeping a limited zone size to effectively deter drug dealing from the immediate vicinity of the property.21 These findings are consistent with elements of other place-based crime studies, including those focused on homeless shelters.

Policymakers should create drug-free zones around services that offer housing, shelter, or other assistance to homeless individuals. These policies should focus on deterring the encroachment of the illegal drug market into the vicinity of homeless services, but also hold facilities accountable for creating a safe and secure environment for their clients. Drug-free homeless service zone laws enhance criminal penalties for selling or transferring narcotics within 300 to 500 feet of a facility—the radius range that studies found was most susceptible to criminal activity around a homeless shelter or supportive housing facility.

The second component of the law includes financial penalties for homeless service providers who permit (either in policy or practice) the possession or use of illegal drugs among their clients. It is increasingly common for homeless service providers to permit drug use in their facilities and de-emphasize treatment as part of a “harm reduction” approach to housing.22 Because of this predatory dynamic, drug-free homeless service zones should penalize service providers for failing to maintain a safe environment for their clients by enabling drug use among them instead of fostering a treatment-oriented environment. Providers who turn a blind eye to a dangerous environment for the vulnerable population they serve should be punished. Fining facilities would create a powerful incentive for service operators to prioritize treatment and other interventions rather than enabling dangerous behaviors like drug use.

Conclusion

The connections between drugs, crime, homelessness, and facilities that provide services to the homeless are alarming. Many service providers, encouraged by federal agencies, have neglected the risks posed by drug use and crime to homeless individuals and the community. Policymakers need to do more to intervene properly in this growing crisis by holding both criminals and service providers to account for contributing to the problem. Creating drug-free zones is a proven model that can help save lives, reduce crime, and restore order to America’s streets.

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about our fight for policies at the state level that restore liberty through transparency and accountability in American governance.