Confronting Regulatory Inertia

State and Federal Lawmakers Must Implement Robust and Mandatory Regulatory Review to Improve Market Health and Human Outcomes

Introduction

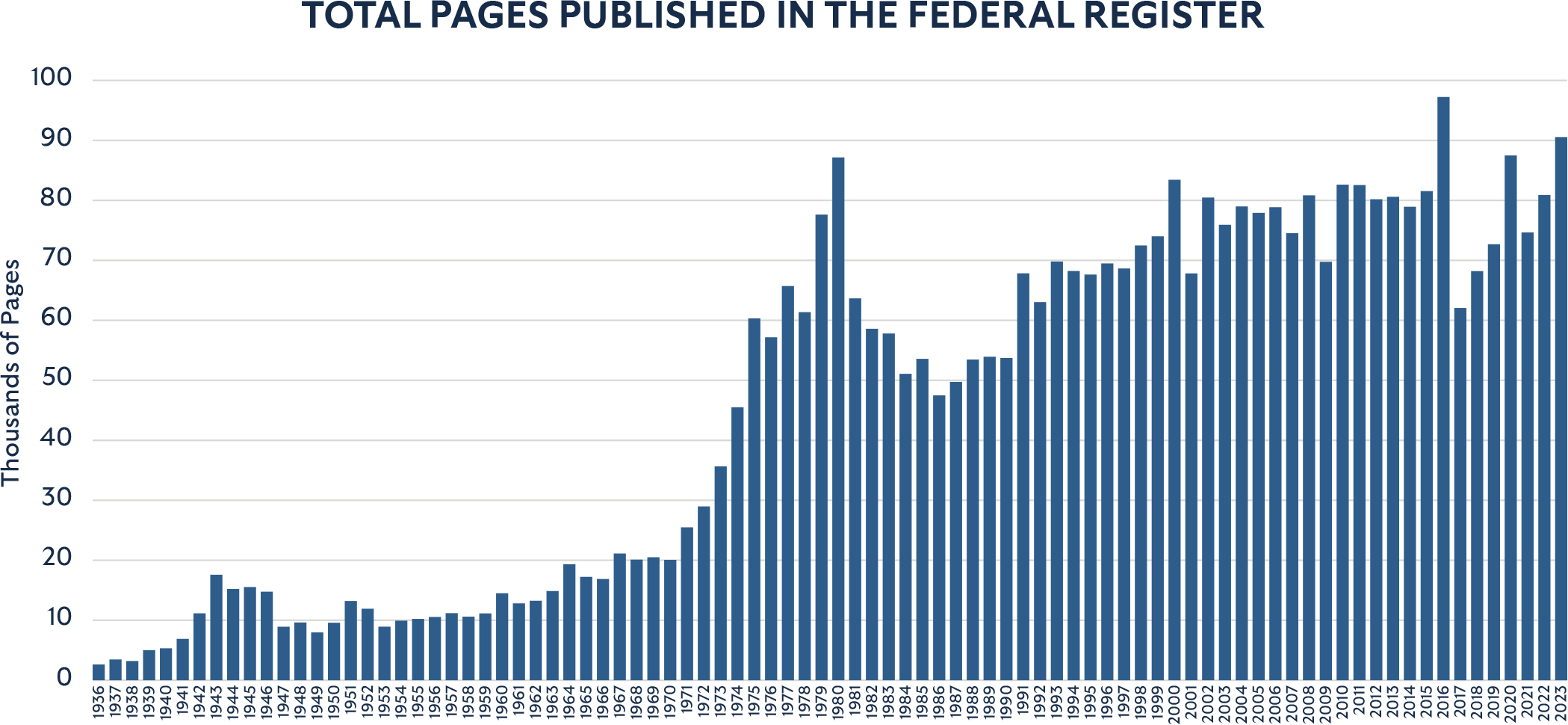

Recently, Elon Musk likened excessive government regulations to Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels.1 “If the nation is Gulliver, it’s being tied down by one little regulatory string at a time. Eventually, you have millions of strings, and the giant can’t move.” While Musk’s audience was Italian, his wisdom is no less relevant here in the United States. The Federal Register, America’s index of federal regulations, exceeds 63,000 pages; between 3,000 and 4,500 new rules are published each year and, for 25 of the last 26 years, federal agencies have added at least 50 new regulations with at least a $100 million impact on the economy.2,3,4,5 The American Action Forum estimates that new federal regulations have imposed more than $1 trillion in economic costs over the last 3.5 years.6 State regulations pile atop these federal rules, increasing the burdens on workers, businesses, and consumers. Musk continued, “There needs to be something where we delete rules, regulations, and laws. If all we do is add them, eventually, we will be able to do nothing.”

Source: Columbian College of Arts & Sciences Regulatory Studies Center7

Musk’s suggestion is apt, underscoring the tenuous relationship between American regulatory agencies, lawmakers, and citizens. Endowed with broad rulemaking authority via statute and afforded deference from the courts, regulators operate with substantial discretion and lack a check against overregulation. In protest, presidents such as Reagan and Trump put regulations on the chopping block only for their work to be undone by their successors. As economists and entrepreneurs alike lament red tape from state and federal authorities, it becomes clear that America needs a sustainable deregulation practice. Ever-growing overregulation demands procedural solutions. Specifically, regular, transparent, and mandatory regulatory review and rule deletion is necessary to prevent market disruption and ensure that federal and state regulatory regimes serve the public interest. Cicero Institute policies, including automatic sunsets and cost-benefit analysis, evaluate every regulation, and automatically eliminate those that harm market efficiency without any benefit.

Misaligned Incentives Among Regulators and Interest Groups Foster an Inefficient Regulatory Environment

At their best, regulations should provide clarity when the legislature passes a law designed to improve human welfare or address market failures. Legislation often leaves gaps and regulations fill those gaps so the public can fully understand the rules of the road. These necessary and non-capricious rules aspire to correct market failures such as the tragedy of the commons and incentives that produce moral hazard. Indeed, even Hayek calls for laws to protect the commons. However, we share Musk’s concern that regulations often outlive their usefulness and become costly for taxpayers and burdensome for business. Sam Huntington’s theory of political decay illustrates the general tendency of political institutions to deviate from their initial purpose and devolve into arenas for political conflict.8 Problems require solutions, but old solutions may soon yield new problems. In the world of American rulemaking—absent a robust and regular regulatory review process—agencies risk regression. In short, regulations that once addressed a legitimate market failure may today impede market function.

Moreover, just as no one string bound Gulliver, otherwise beneficial rules may thwart the public interest when stacked atop an already mammoth regulatory burden. In a vacuum—a perfectly competitive market—well-intentioned regulations may serve a legitimate public interest. But regulatory idealism is detached from reality, the most highly regulated market environment in American history. Thus, already tied down by multiple regulations, even legitimate new rules may be the final cord that incapacitates the business. To use another idiom: overregulation is death by one thousand cuts.

At the core of American overregulation is a crisis of incentives, checks, and balances. Regulators are motivated to write new regulations, unmotivated to eliminate old regulations, lawmakers and courts are deferential, and the most prominent industry participants prefer regulation to stymie their competition.

Incentives among both state and federal regulators ensure the proliferation and maintenance of regulations long after market failures have been corrected. Careerist bureaucrats are motivated to mint new regulations and justify their agencies’ budgets. Likewise, political appointees may be tempted to view rulemaking as a tool to actualize ideological ends and win political battles rather than address market failures. Both groups are motivated to generate new rules and neglect old ones, compounding the Federal Register and its state-level corollaries. Unfortunately, there are few incentives to withdraw old regulations, or even exert energy to review old regulations. This regulatory inertia entrenches industries in a climate of oppressive government scrutiny and crushing compliance costs.

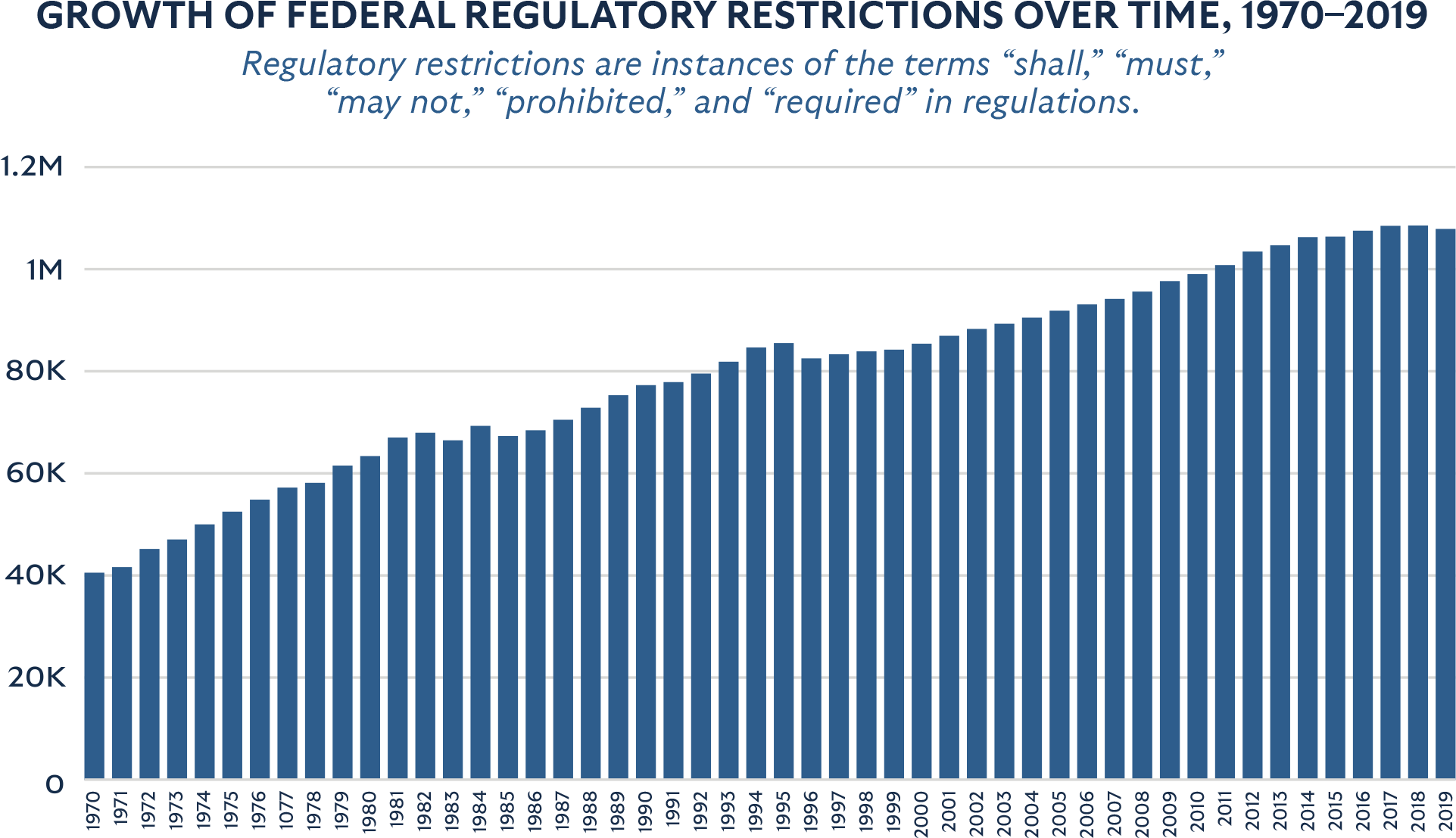

Source: QuantGov9

Regulatory inertia is a problem because outdated regulations divert regulators and regulated entities from the public interest. Old rules may cite outdated laws, ignore new technologies, and can remain on the books even if unused for decades. Indeed, regulations devoid of a reasonable cost-benefit assessment and incongruent with the public interest continue to carry the force of law long after their relevance expires. Every business still must obey old rules or risk retribution, even if old rules are no longer enforced. The costs of regulations continue to grow, more strings continue to tie down Gulliver, and progress is slowed or ultimately stopped.

Regulators are not entirely to blame, as deferential and disinterested lawmakers share significant culpability. Every one of the 438 federal agencies and sub-agencies is ultimately a creature of congressional statute.10 At the federal level, Article I lawmaking increasingly resides in Article II agencies because Congress fails to write clear statutes or even intentionally delegates the tough decisions to the regulators.

State legislators are often no less guilty of such an offense and should rightly share the blame for the proliferation of state regulations. Rather than doing the hard work of crafting statutes that can be enforced without significant regulatory clarification or holding agencies accountable when their regulations extend far beyond the legislature’s intent, legislators often prefer to write a bill, claim the “win,” and then blame agencies if something goes wrong on the regulatory front. And for too long courts have dismantled the separation of powers both by enabling Congress to delegate legislative authority and by upholding a deferential standard to rubber-stamp agency rules.

In 1928, the U.S. Supreme Court first invited Article II agencies into the lawmaking arena with J. W. Hampton, Jr. & Co. v. United States, holding that the delegation of legislative authority is a constitutionally implied power of Congress insofar as delegations are guided by an “intelligible principle.”11 From these reasonable beginnings, the crucial checks against agency abuse quickly began to erode. Throughout the remainder of the twentieth century—as the scope and authority of the executive branch grew at a breakneck pace—the judiciary built upon Hampton, Jr. & Co., becoming increasingly deferential to the executive bureaucracy.

Most notably, in Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. (1984), the Supreme Court ruled that courts must defer to agency expertise when laws are ambiguous, arguing that statutory ambiguities represent implicit delegations from Congress so long as agency interpretations are reasonable.12 And just a few years later in Mistretta v. United States (1989), the Supreme Court encouraged exactly the kind of statutory ambiguities that Chevron positioned agencies to exploit, ruling that Congress must delegate to agencies “under broad general directives.”13 While the Supreme Court weakened Chevron deference and restored some elements of nondelegation in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, it is clear that nearly one century of deferential jurisprudence is partially responsible for America’s ongoing regulatory troubles.

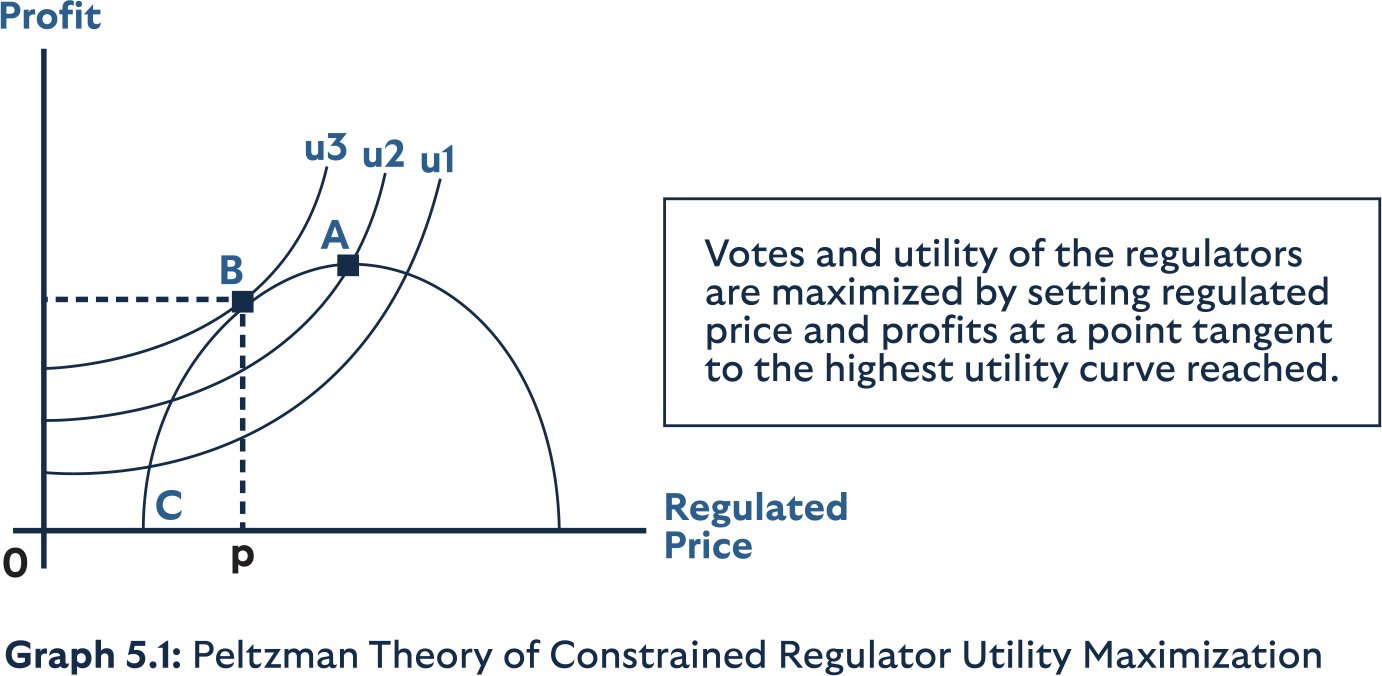

More troublesome, economic theory suggests that many regulations are not oriented by the public interest and instead impede market efficiency by design. The University of Chicago School’s Stigler, Friedland, Pelzman, and others famously challenged idealistic public interest theories with the so-called “economic theory of regulation.” Stigler contended, “Regulation is acquired by the industry and is designed and operated primarily for its benefit” (Stigler 71, 3).14 In other words, rather than sound the alarm about new regulatory burdens, rent-seeking interest groups and the largest market actors seek out favorable regulations, yielding higher compliance costs for their competitors and deadweight losses for society. Pelzman pointed out that this regulatory capture means the regulated price of goods and services will always be suboptimal. Profits of the regulatory cartel—rent-seeking interest groups and career- or political-minded regulators—catalyze higher prices for consumers.

Source: James Edwards, The Economic Theory of Regulation; Regulation, the Constitution, and the Economy, chapter 5, p. 77.15 In this diagram, point C is the unregulated price, B is the regulated price, and A is the monopoly price.On the y-axis, profits of the regulatory cartel motivate higher prices (the x-axis), rendering deadweight losses.

Overregulation Slows the Economy and Thwarts the Public Interest

Empirical analysis corroborates these Chicago School arguments, demonstrating the economic burden of overregulation. The National Association of Manufacturers found “the total cost of complying with federal regulations in 2022 is an estimated $3.079 trillion (in 2023 dollars), an amount equal to 12 percent of U.S. GDP.”16 The same study estimates the average cost of regulations to be $277,000 per firm and $29,100 per employee in manufacturing. Another analysis, from the Competitive Enterprise Institute, estimates the total economic cost of regulation to be $1.939 trillion and $14,514 annually per household.17 Across all industries, regulatory compliance costs continue to rise. In February 2023, the National Bureau for Economic Research found that regulatory compliance costs grow by a full one percent each year.18

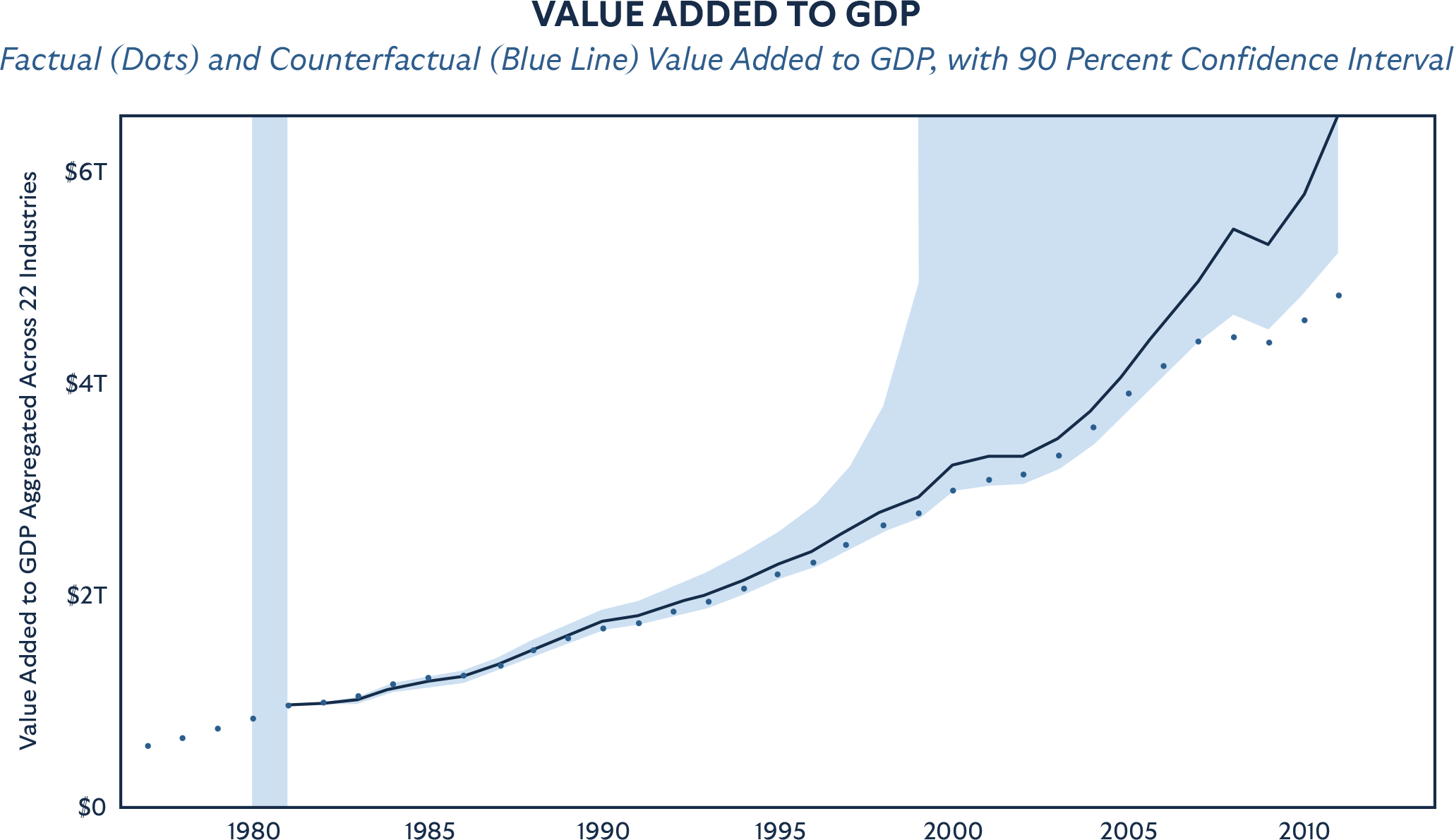

Beyond direct compliance costs, regulatory inertia also deters positive economic activity by discouraging business growth and formation. The Mercatus Center at George Mason University analyzed 22 industries over 35 years and examined a counterfactual scenario where the Reagan-era regulatory environment had persisted to 2012.19 Mercatus concluded that tedious regulations were responsible for a 0.8 percent annual reduction in GDP, resulting in an approximately 25 percent smaller economy in 2012 than if 1980 conditions had prevailed. While the precise cost of business deterrence is unknown, overregulation are the cords that work together to stunt economic growth by discouraging investment and innovation.

Source: Mercatus Center

More importantly, burdensome regulations stymie efficient business, creating downward pressure on wages and upward pressure on prices. Consequently, after controlling for other variables, Mercatus concluded that “a 10.0 percent increase in federal regulations … is associated with a 2.5 percent increase in the poverty rate.” In sum, “an estimated 6.9 million additional people lived in poverty in 2019 as a result of increased federal regulations.”20

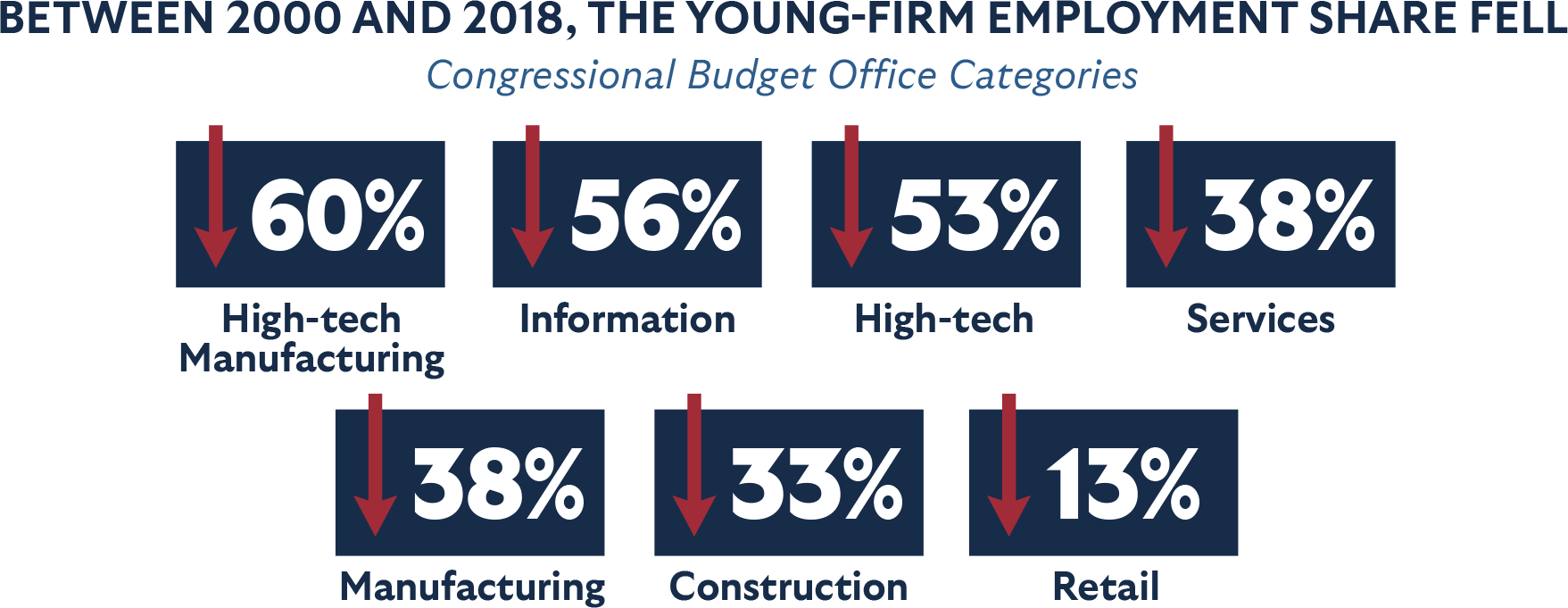

Less discussed, but cumulatively even more burdensome, are the added regulatory strings imposed by state governments. State regulations are not uniform, require different compliance reporting and processes, and often conflict with other states or the federal rules. Onerous state and local regulations stunt business growth and formation. The Cato Institute reports, “Between 2000 and 2018, the young-firm employment share fell 60 percent in high-tech manufacturing, 56 percent in information, 53 percent in high-tech, 38 percent in services, 38 percent in manufacturing, 33 percent in construction, and 13 percent in retail.”21 The culprits, per Cato, are state and local barriers to new business formation. At the state level, legal obstacles, mandated costs, and even outright bans on business formation in specific sectors discourage would-be entrepreneurs. At the municipal level, complex permitting and licensing requirements, corruption favoring incumbent firms, and zoning rules hostile to home-based businesses—the incubation chambers for many of today’s S&P leaders—impose oppressive costs on innovators. These municipal and state regulations make growth, expansion, and opportunity more difficult for multi-state businesses.

Source: Congressional Budget Office (https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56945#footnote-103)

The humanitarian toll of overregulation becomes most apparent at the state level. According to a 2016 ranking of U.S. states by the Federal Regulation and State Enterprise Index—a measure of the total economic cost of regulation in a specific jurisdiction—Louisiana ranked first, or most costly, with a 74 percent higher regulatory burden than the nation overall.22 It should be no surprise that Louisiana also endures the nation’s third highest poverty rate.23

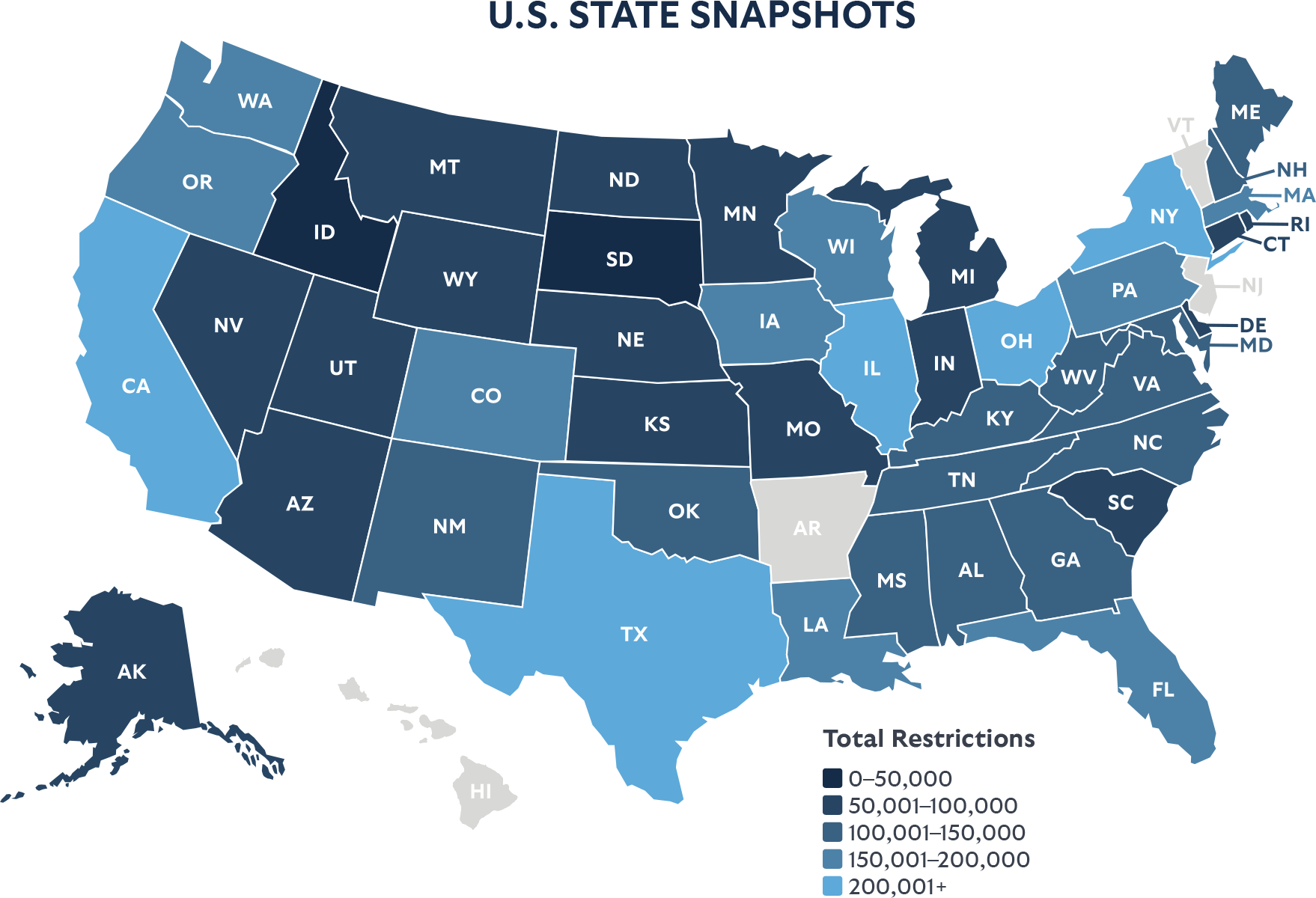

Markets also bear the brunt of state-level regulations, which ensnare businesses in a different kind of struggle. In total, state-level regulations contain 416 million words and each state presents 135 thousand regulatory restrictions to consumers and firms on average.24–25 Overshadowed by federal regulations, even conservative states oversee burdensome regulatory regimes, with Ohio and Texas ranking fourth and fifth respectively, among the National Review’s most regulated states.26 While Idaho is a regulatory leader with only 38,961 restrictions as of 2020, Texas’ and Ohio’s excess of more than 250,000 restrictions put them in close company with New York and Illinois.27

Businesses struggle to succeed when overwhelmed by state and municipal red tape. First, a patchwork of uncoordinated state rules pose challenges to interstate firms that must comply with each state-level regime. Many small businesses are discouraged from growing beyond their local jurisdictions, curbing competition and slowing the nation’s rate of innovation. Second, state regulations are often incongruent and sometimes in outright conflict with federal regulations. In certain cases, the scope of the regulatory burden faced by a particular industry or business is unclear to the market. This regulatory uncertainty further tightens the metaphorical strings restraining the giant that is the American economy.

Most state regulators have no obligation to regularly compare the regulatory burdens of their state with those of nearby states. States that have gone through such an exercise have found significant opportunities to remove burdens on their citizens. In 2017, Idaho Governor Brad Little considered the state’s occupational licensing burdens and compared them to those of surrounding states. By implementing sunrise and sunset policies and regular review, Little’s Licensing Freedom Act significantly reduced the regulatory burden.28 Moreover, both Iowa’s and Idaho’s universal licensing recognition laws—accepting out-of-state licenses for work in their respective states—resulted in substantial employment, job creation, and migratory benefits.29 However, in most states, occupational licensing requirements and other crushing regulations continue to stifle labor markets and undermine opportunities for hardworking job seekers. Indeed, regulatory inertia pays no attention to an ever-increasing burden, a differential in burden across states, or the impacts of those burdens on the state’s citizens and businesses.

The Cicero Solution: Regular, Transparent, and Mandatory Regulatory Review

To overcome inertia, one needs an equal and opposite force. Citizens, governors, elected lawmakers, and courts need to confront regulatory-agency overreach. Checks and balances can quell the inertia of regulation. States should learning from successful deregulators, create transparency through technology, and hold bureaucracy accountable to the public.

Learn From Successful Deregulators

The handful of deregulatory presidents and governors demonstrate the potency of an executive check against overregulation. Indeed, to date, only executive branch leaders who specifically prioritize deregulation have effectively reduced the overall regulatory burden. At the federal level, President Reagan campaigned to deregulate finance, agriculture, and transportation. His administration fueled an economic climate of business formation and innovation, delivering the U.S. from a decade of stagnation.30 More recently, President Trump’s focus on deregulation resulted in billions of dollars in cost savings for businesses, workers, and consumers. One 2021 analysis measured the Trump administration’s total regulatory costs on the economy at $10.1 billion annually, less than 10 percent of Obama’s $111 billion average, and roughly one quarter of George W. Bush’s $43 billion yearly burden.31

However, holding out for a deregulator-in-chief is an imperfect solution to the crisis of overregulation. While President Trump managed to reduce regulatory burdens by an estimated $220 billion per year—making regulatory cost savings a required metric for every cabinet agency—most of his work was immediately undone by the Biden administration, which today oversees perhaps the most expansive federal regulatory regime in U.S. history.32–33 Deregulators are the exception, not the rule, and the quantity and magnitude of federal and state regulations have substantially increased in the last 50 years.

Unaccountable bureaucrats know that every deregulatory chief executive will eventually leave office and then the regulatory machine can revive. To address this challenge, states and the federal government need statutorily mandated bulwarks against overregulation. Sunsets require every regulation to undergo a regular and systematic review process then automatically expire. If the legislature thinks a regulation should be permanent, it can codify it as a statute. Otherwise, regulations do not need a permanent lifespan. Sunsets systematically end rubber-stamp renewals by requiring agencies to carefully scrutinize their current regulations every 5-10 years. This full re-vetting ensures that each regulation is still necessary, the least burdensome to regulated entities, and most beneficial to the public interest.

Sound cost-benefit analysis requirements ensure that the total projected benefits of any rule must exceed its projected costs across multiple time horizons. These data should call upon insights from affected stakeholders and all data and methodology should be publicly available online. Citizens should be able to challenge the validity of rules solely on the basis of problems in the CBAs. If agencies neglect the cost of a rule on an individual or business, that stakeholder ought to have standing to contest the regulation in court.

States can lead the way in teaching one another—and the federal government—how best to address, slow, and reverse regulatory inertia. For example, Montana’s Red Tape Relief Act demonstrates the role legislatures can play in successful deregulation. The law aims to “conduct a comprehensive, top-to-bottom review of regulations in every state agency.” In 2023, Governor Greg Gianforte signed 54 red tape relief bills designed to simplify and modernize state codes.34 The U.S. Congress should follow Montana’s lead, reasserting the appropriate function of Article I and demanding that federal agencies adhere to regulatory review procedures.

A sound regulatory review procedure would improve market efficiency, promote human welfare, and foster public buy-in. Lawmakers should focus on procedural integrity and emphasize transparency. They should also deploy modern technology to create accountability and cultivate public engagement.

Implement Technology-Based Transparency

Technology-based transparency standards would disclose what regulations are under review, how those regulations will be evaluated, when regulations will be coming up for review, and any revisions or changes that regulators propose. Modern technology enables state and federal bureaucrats to show their work by sharing their reasoning for keeping or removing each rule, making every study they cite and all underlying data available to the public. Regulatory decisions, cost-benefit analyses, methodologies, and underlying data should all be published online in a searchable and machine-readable format to enable public scrutiny. Technology can also help the public to easily access regulations on the internet, review what changes are being proposed, and provide comment to agencies. Internet publication and communication tools are ubiquitous in the private sector; now it is time for federal and state governments to catch up, leveraging already existing technologies to actualize transparent and accountable rulemaking.

To effectively utilize technology, lawmakers must call upon industry experts while simultaneously prioritizing public engagement. William Eggers’ Government 2.0, outlines two futures: one where the American government neglects modern technology, drowns in red tape and stagnates, and another where the government utilizes technology to improve economic opportunity.35 Lawmakers have a clear and important opportunity to pursue this second kind of future when addressing the regulatory crisis.

Existing frameworks should inform review procedures. State and federal administrative procedures acts (APAs) often provide sound systems for regulatory oversight. The federal government’s APA outlines clear and praiseworthy standards: regulators must act within limits set by statute and meet tests for reasonableness that are not arbitrary, capricious, or abusive. They must also follow specified procedures that include provisions for public notification and consideration of public comment. Agencies must follow these rules, and courts regularly hold them accountable when they fail to comply by rejecting rulemaking that do not meet the APA’s strict procedural standards.

The public deserves to know what is going on inside a rulemaking agency, and the agency should not be able to issue a renewed regulation without seeking and responding to public comments. But the public needs an ally, and so courts also have a role to play in limiting regulatory inertia.

Foster Accountability to the Public

By striking down regulations that fail to involve the public, incorrectly weigh costs and benefits, or increase an agency’s authority beyond the legislature’s intent, the courts can simultaneously combat overregulation and ensure their vital role as protectors against unaccountable government overreach. Regardless of whether the Supreme Court overturns Chevron or changes its standards for deferring to an agency’s interpretation of statutes, the lower courts can and should ensure the agencies strictly adhere to procedural rules that incorporate careful weighing of costs and benefits and public participation in the rulemaking.

Additionally, accountability standards would enhance regulatory review by highlighting the specific role of regulators. The public should be able to know which agency office is signing off on a decision, what officials in the executive branch are approving a regulation, and whether there are senior officials in the president’s or governor’s office who play a role in ensuring regulations—both new and old—are aligned with the policy agenda the voters selected when they chose a chief executive. Accountability also means that if an agency’s justification for a regulation turns out to be faulty, the regulation will be withdrawn.

Once again, technology can foster accountability by tracking approvals across the government to make sure that the public can easily confirm who is responsible for approving a regulatory decision. In the long term, technology can help to flag predictions in regulatory proposals and build metrics that can be tested in the months and years after a regulation is on the books. If those predictions are wildly inaccurate, agencies should be required to return to the drawing board to either modify the regulation or wholesale withdraw it and try a different approach. Regular review should consider and evaluate the accuracy of such measurements, emphasizing effective prediction methodology across extended time horizons.

Finally, transparent and accountable regulatory review must be mandatory. In the status quo, agencies lack the incentive to perform a complicated review of the entire code of regulations on a regular basis. But if those regulations automatically expire but-for a review, agencies will prioritize the review for the most critical and valuable regulations. Technology can streamline this process to make agency regulatory review and revision much less tedious. Mandatory review will also equip courts with the statutory authority to sanction noncompliant regulators.

Conclusion

After freeing his left arm, Gulliver uprooted the Lilliputians’ ropes and escaped their trap. While America’s regulatory restraints appear debilitating, creative and forward-looking state and federal lawmakers can promote market health by advocating for mandatory regulatory garbage collection. Regularly scheduled regulatory review laws should emphasize transparency, accountability, and modern technology’s role in reducing the regulatory burden. The results are clear: effective deregulation heals markets, fuels innovation, and promotes human flourishing. America’s regulatory environment should echo the competitive principles of a free society.

Just as free speech enables the competition of ideas, free markets foster competition for resources and capital. In both domains, free and open competition catalyzes innovation and yields prosperity. Excessive regulation threatens to undermine free competition, jeopardizing the integrity of our republic. By restoring checks and balances, a legislative response to overregulation offers an exciting opportunity to enhance our free society.

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about our fight for policies at the state level that restore liberty through transparency and accountability in American governance.