A Street Camping Ban for a Safer Idaho

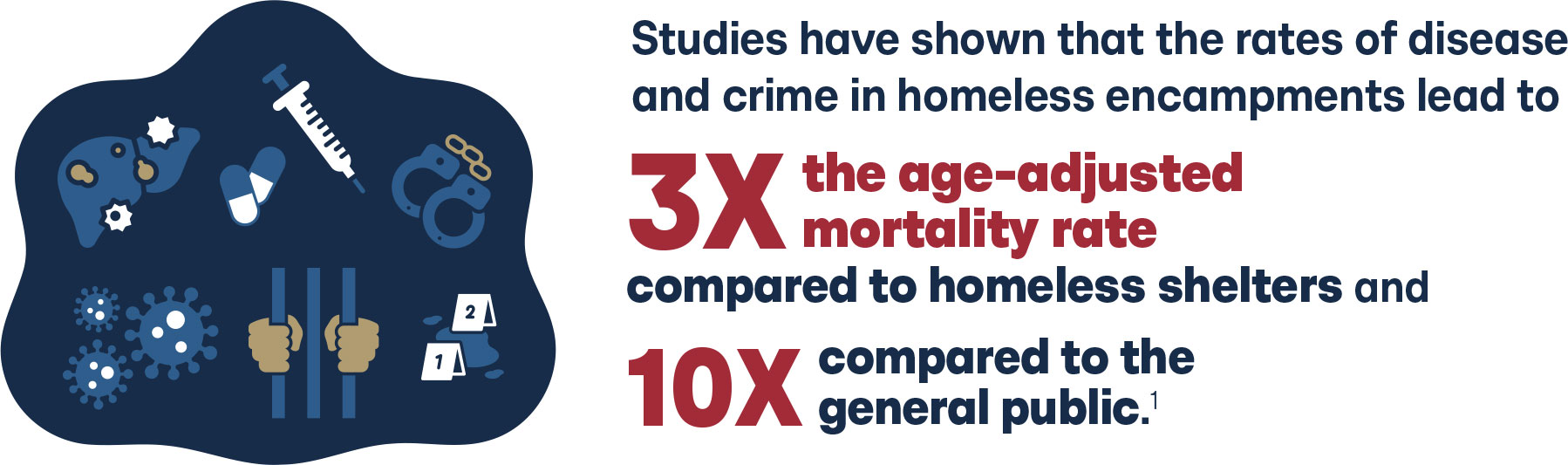

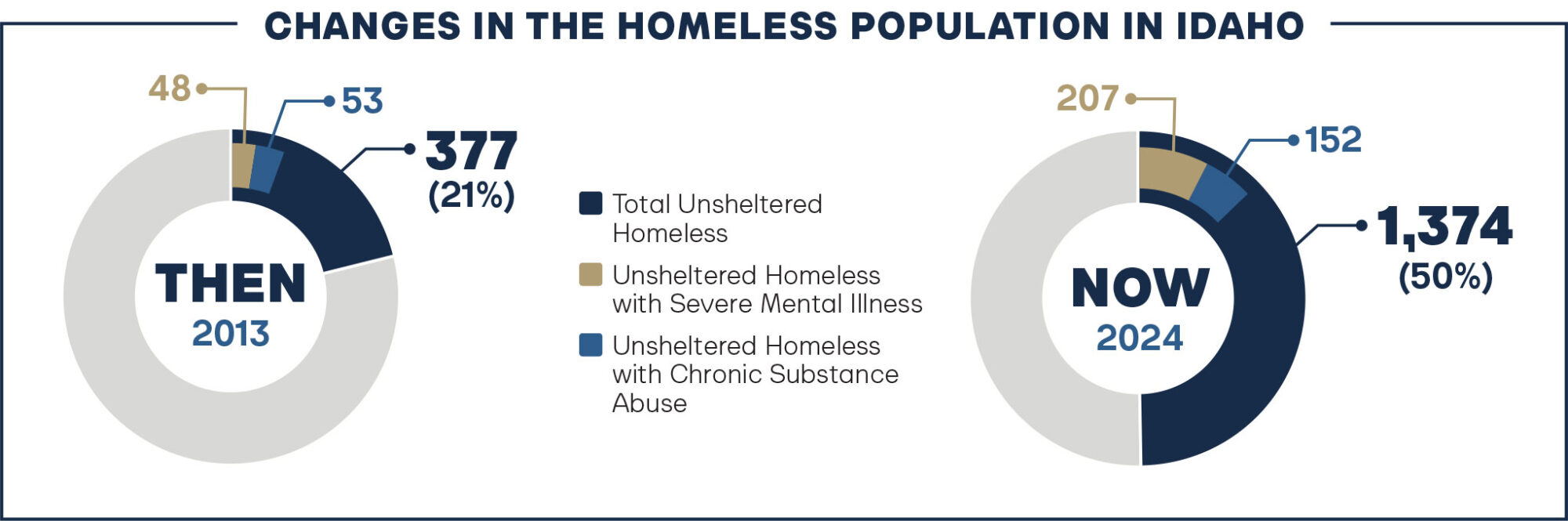

Unregulated homeless encampments are a danger to both the public and homeless people.

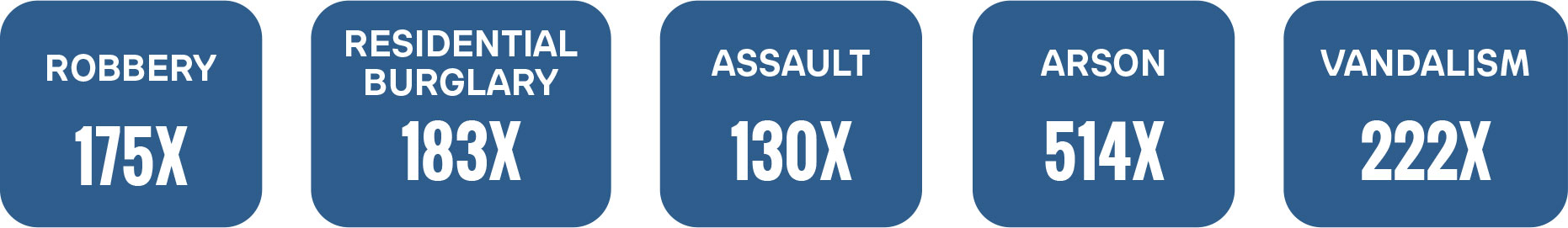

A report from a district attorney’s office in a large city found that homeless people were hundreds of times as likely to commit crimes like robbery or arson, and dozens of times as likely to be victims of crime.2

A report from a district attorney’s office in a large city found that homeless people were hundreds of times as likely to commit crimes like robbery or arson, and dozens of times as likely to be victims of crime.2

Prohibiting unauthorized street camping ensures that cities in Idaho do not neglect vulnerable people in crisis who are living on the street.

How has it worked in other states?

According to data from the Kentucky Administrative Office of the Courts, in the first six months of enforcement, since the statewide camping ban took effect last summer, out of 1700 total unsheltered Kentuckians, only 19 individuals have received a misdemeanor-level charge. Nearly all those charged with misdemeanors or violations have the opportunity to receive a suspended sentence in exchange for participating in services.

Florida, Georgia, Oklahoma, Texas, and Utah have implemented camping bans but data collection has not been as robust as in Kentucky.

THE BOTTOM LINE:

There is nothing compassionate about leaving vulnerable people in crisis on the streets in sprawling encampments. Regulating street camping creates a modest pressure through engagement with law enforcement to move people off the streets and into shelter where they otherwise might choose not to. Shelters like Boise Rescue Mission have open beds that people could access in order to comply with the ban.

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about our fight for policies at the state level that restore liberty through transparency and accountability in American governance.