2025 Playbook for Certificate of Need Repeal

Ranking Certificate of Need Laws in All 50 States

Certificate of Need Executive Summary

The United States healthcare system is in a state of crisis. Costs continue to rise, patients struggle to access timely care, and providers encounter difficulties in meeting demand. Although the current crisis is multifaceted in its causes, Certificate of Need laws—outdated and restrictive regulations from the 1970s—remain a key policy that perpetuates these issues. Prioritizing the repeal of unnecessary regulatory burdens is a prudent and essential step to improve the current healthcare climate.

In 1974, the federal government required states to adopt Certificate of Need (CON) laws to receive federal healthcare funding. States feared overutilization and higher Medicaid costs, and thought CON was a viable solution to limit the supply of healthcare. After a short time, the Federal Trade Commission and academics soon discovered that CON laws resulted in higher costs for all payers, lowered access, and diminished outcomes. By 1986, the federal government repealed the mandate, and many states subsequently repealed their CON laws.

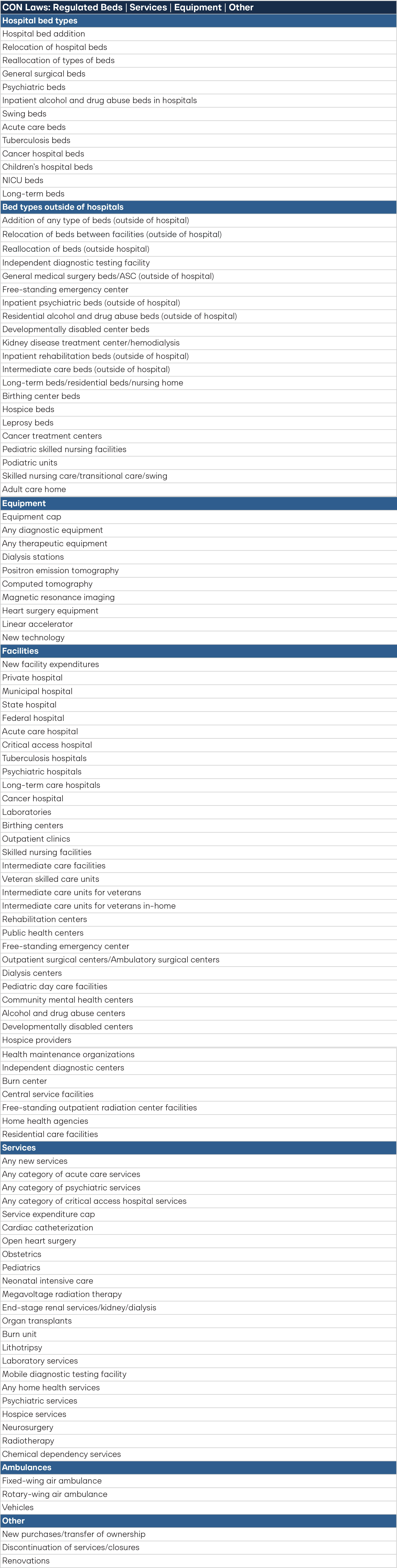

Despite the evidence, 41 states and the District of Columbia still have a form of CON laws on the books. These laws impose requirements to receive approval from an ancillary government body before new medical services, new beds, or new facilities can be established and, in some cases, before new medical equipment can be purchased. A CON application must “prove” the new service is needed to gain permission to provide care. Problematically, many existing competing providers sit on approval boards or pressure the boards to keep new entrants out of the market, in effect encouraging legalized monopolization.

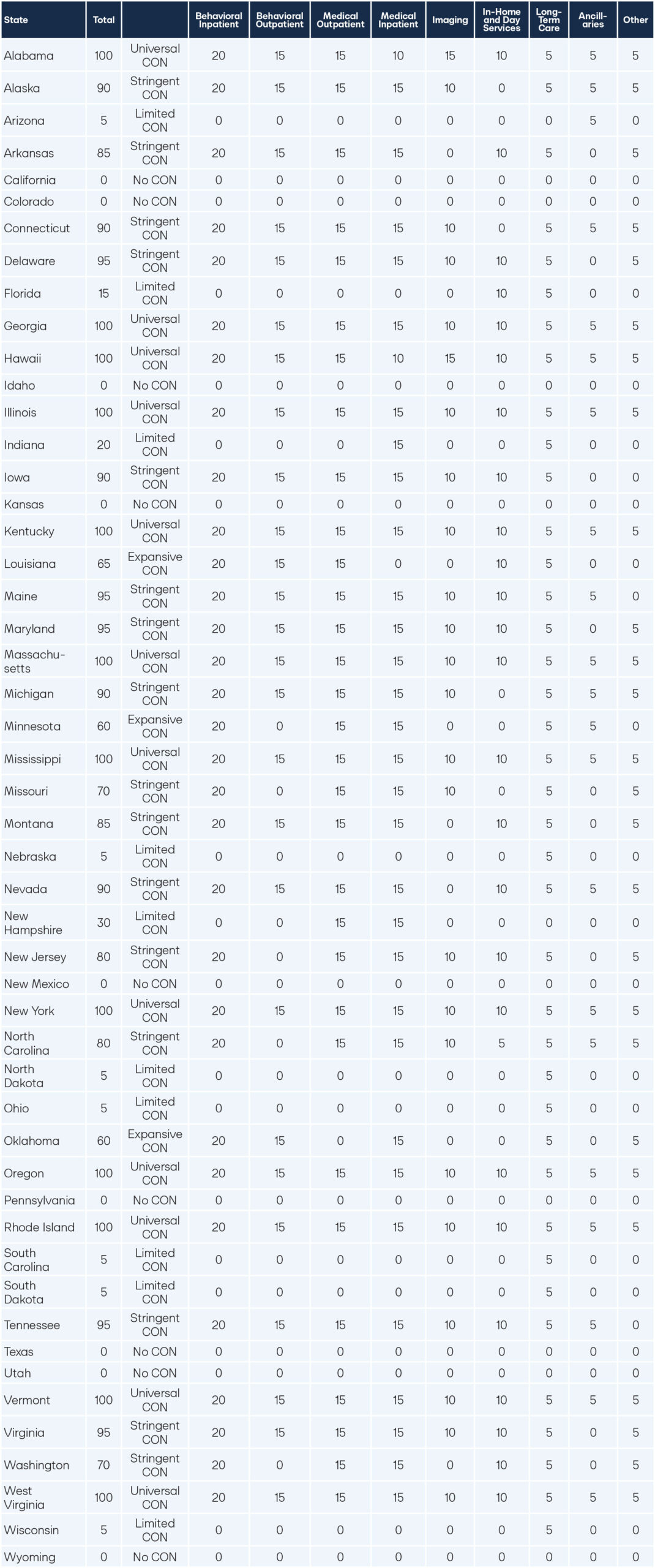

Understanding the relative impact of CON laws in each state can be difficult, as the laws differ widely from state to state in terms of which facilities, beds, equipment, and services require a CON application. To assess Certificate of Need laws nationwide, the first portion of this paper provides an overall score for the expansiveness of CON laws in each state. This ranking utilizes the methodology from the 2024 “Ranking Certificate of Need Laws in All 50 States” paper by the Cicero Institute. The updated 2025 paper will cite specific state codes for each category in the methodology.

The second portion of this paper outlines strategies states can adopt to ultimately achieve full repeal of CON laws. Leveraging political will to repeal CON in the high-needs areas of behavioral health, maternal health, diagnostics, and heart health can create momentum to repeal CON laws for ambulatory surgical centers, hospitals, and long-term care.

Certificate of Need Overview

Impact on Cost, Access, Health Outcomes, and Innovation

Certificate of Need laws enable government entities or existing competitors to arbitrarily determine whether a healthcare service, equipment, facility, or bed is needed in a community. Such decisions slow access and even prevent providers from supplying essential care. For over four decades, experts have sounded the alarm that states should repeal CON laws to improve healthcare.

CON laws originally emerged from a genuine policy concern in the 1960s and 1970s. Medicare’s old cost-plus reimbursement model incentivized costly expansions and excess capacity. To curb this, Congress enacted the 1974 Health Planning and Resources Development Act, which required states to adopt CON programs or lose federal funding.1 The idea was to prevent unnecessary construction and control spending by forcing hospitals to demonstrate a “need” before expanding. At the time, centralized oversight reflected a common belief that limiting supply could constrain costs in a system driven by government reimbursements. All states except Louisiana adopted CON laws.2

However, when Congress replaced cost-plus reimbursement with the prospective payment system (PPS) in 1983 under the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act (TEFRA), the underlying rationale for CON laws vanished. Hospitals no longer profited from overspending, and the market began to self-regulate. Yet the laws remained, and now CON regimes protect entrenched providers, slow innovation, and restrict patient access. States that repeal outdated CON restrictions will ensure patients can get the care they need.

In 1987, Congress repealed the federal CON mandate.3 In 1988, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) published an economic policy analysis demonstrating clearly that CON laws failed to lower healthcare costs and were, in fact, increasing costs.4 However, as of this writing, 41 states still have a form of CON laws on the books.

As originally designed, CON laws explicitly restrict supply, directly impacting whether patients can find a provider or even afford to pay for their care. Additionally, when there is little competition in a market, there is no natural incentive to improve the quality of services. For most businesses, an individual is simply required to notify the local government, obtain any necessary business licenses, and comply with safety standards to provide services. The government typically does not have the authority to deny or approve the intent to start a specific type of business. Under CON laws, new entrants in the market must apply for and receive approval (sometimes from their own future competitors) before they can open the facility or provide the service.

The following sections evaluate several of the adverse effects of CON on cost, access, innovation, and health outcomes (especially in behavioral, maternal, diagnostic, and heart health).

Cost

Economic principles demonstrate that when supply is restricted, demand rises, leading to higher prices. Healthcare is no exception to this rule. In fact, the effect is often worse because healthcare services are generally inelastic, meaning there is no suitable substitute. For example, if peanut butter prices skyrocketed, people could buy almond butter instead. But if substance abuse clinics or other specialized healthcare services are essentially capped by CON laws, there are often no suitable substitutes. No alternative means forgoing treatment or paying exorbitant costs. Forgoing treatment can exacerbate symptoms, leading to higher healthcare costs and poorer outcomes over time.

Certificate of need laws circumvent natural competition by granting a government entity the power to predetermine winners and losers. No entity can accurately predict winners or losers or determine whether something is needed. As competition in the healthcare market dwindles, hospital consolidation rises, resulting in fewer choices for patients and greater market power for providers to charge higher prices for the same services. In the healthcare industry, the problem is compounded by a lack of price transparency.5 Not only do patients have few options for care, but they often have no idea how much a visit will cost until a bill appears in the mail. Additionally, as consolidation increases, hospital systems tend to relocate to urban areas, leaving rural communities without access to essential care. One economic model found that unhealthy individuals in CON states spent 12 percent more for healthcare than unhealthy individuals in non-CON states.6

For hospitals, CON laws lead to 10 percent higher spending, which was known as early as 1991.7 Even health planners, the original advocates of centralized planning for healthcare resources, testified in the U.S. Congress that CON laws did not work as intended.8 Five years after the repeal of CON, hospital charges decreased by 5.5 percent.9 For hospitals to be approved to provide some types of complicated services, such as heart surgery or neurosurgery, a CON review is required by states. After CON repeal in Pennsylvania, the cost of coronary bypass grafts lowered by 8.8 percent in the state.10

Some argue that CON repeal may be effective in lowering costs for private payers, but not for reducing costs for Medicaid and Medicare. However, restricting the supply of facilities and services drives up the costs for all payers—private, yes, but also for Medicaid and Medicare.11 Restricting facilities does not control costs; it consolidates the market geographically and economically in a way that harms patient access and state budgets.

For example, nursing homes rely predominantly on Medicare payments. Yet states with nursing home CONs have higher expenditures per resident.12 Similarly, states with CON spend on average $300 more on rural Medicare patients than other states without CON, with worse outcomes.13 Although payments remain the same for nursing homes, overall program costs decrease because businesses can operate more efficiently and competitively without CON restrictions. Without CON, nursing homes can swiftly move beds to where they are needed, rather than relying on permission to provide care. Many home health services also rely heavily on Medicaid payments. CON laws are associated not only with fewer agencies per 1,000 residents, but also with higher Medicaid costs for home health services.14

In addition to increased costs for private and public payers, uninsured patients pay more out-of-pocket costs in states with CON restrictions.15 Charity care, which is uncompensated medical services furnished by nonprofit hospitals to those who cannot pay, does not increase in states with CON laws.16

The negative impact of CON is not limited to patients. Providers endure lost opportunities as a direct result of CON regulations. According to one scholar, “…providers lose the opportunity to provide services and generate revenue. This lost revenue can amount to hundreds of thousands of dollars in opportunity costs…one analysis found that the approval rate in Virginia was 51%, that of Georgia was 57% and that of Michigan was 77%.”17 Applying for a CON review can also be expensive. CON application fees range from hundreds of dollars to hundreds of thousands of dollars (D.C.’s maximum application fee is $300,000).18 The extensive CON application process can take months or even years, and hiring expensive policy or legal experts may become necessary to navigate the process effectively. Not captured in those approval rates are the potential providers who are deterred by the CON process and its associated costs from the outset and decide not to proceed with an application in the first place.

Large healthcare systems and hospitals face a mitigated risk from denied applications, as existing providers can recover lost costs. However, for small independent providers, the application fee itself can be a barrier, as there is no assurance of recouping these costs if the application is denied.

In states that have repealed CON laws, spending by physicians and hospitals decreased by four percent after just five years.19

Access

Lack of healthcare access caused by CON laws harms all residents, but disproportionately so for those in rural and underserved communities.20 Even when CON applications are ultimately approved and new facilities and services are not stifled, the delays caused by the application process put access to medical care out of reach for those in need. Although timelines vary greatly depending on the state, studies find that approval processes can often take four to 12 months.21–22 However, for facilities and services that do not gain approval, it can mean an overall loss to the community.

Following repeal, many hospitals and other healthcare providers open new facilities or introduce new services, particularly in rural areas. For example, since Florida’s broad CON repeal, three hospitals opened in 2022: UCF Lake Nona Hospital, Sarasota Memorial Hospital Venice, and HCA Florida University Hospital. No Florida hospitals have closed as a result of CON repeal. One causal analysis of states with recent repeals found that the number of hospital facilities significantly increase in both rural and urban areas. Interestingly, the average bed count for each facility decreases.23 This suggests that without the restrictions imposed by CON, facilities can right-size their delivery to meet the local population’s needs. It enables facilities to be more agile across a wider geographic area. With CON restrictions, facilities tend to bank on putting more beds in centralized locations, which means longer drives for rural residents.

Policy reforms that reduce CON restrictions also increase the number of medical service providers, expanding life-preserving healthcare access in medical deserts. For ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs), repeal leads to a per capita increase of 92–112 percent in rural areas specifically.24 The impact of increasing access to critical care in rural areas cannot be overstated, where travel time can be the difference between life and death.

Hospital systems tend to argue that while CON would lead to an increase in ASCs, the new services would target the low-hanging fruit (low-difficulty, high-reward services) that hospitals say they depend on, thus impacting a hospital’s ability to remain open. However, the same study that found repeal leads to a 112 percent per capita increase in ASCs also improves access to hospital services. ASCs are overwhelmingly owned by independent physicians, which can attract a fresh workforce to rural areas and retain them there.25 The new workforce can dually work at ASCs and hospitals, especially if they provide specialized care. Additionally, opening ASCs in rural communities leads to wider coverage areas, which enables hospitals to tap into new patient populations and receive more referrals.

When states attempt to repeal CON, hospital systems frequently contend that repeal will force closures, especially for critical access hospitals. They argue that without a guaranteed market share, new facilities could put them out of business, harming patient access. However, in practice, CON repeal can actually benefit overall hospital revenue.

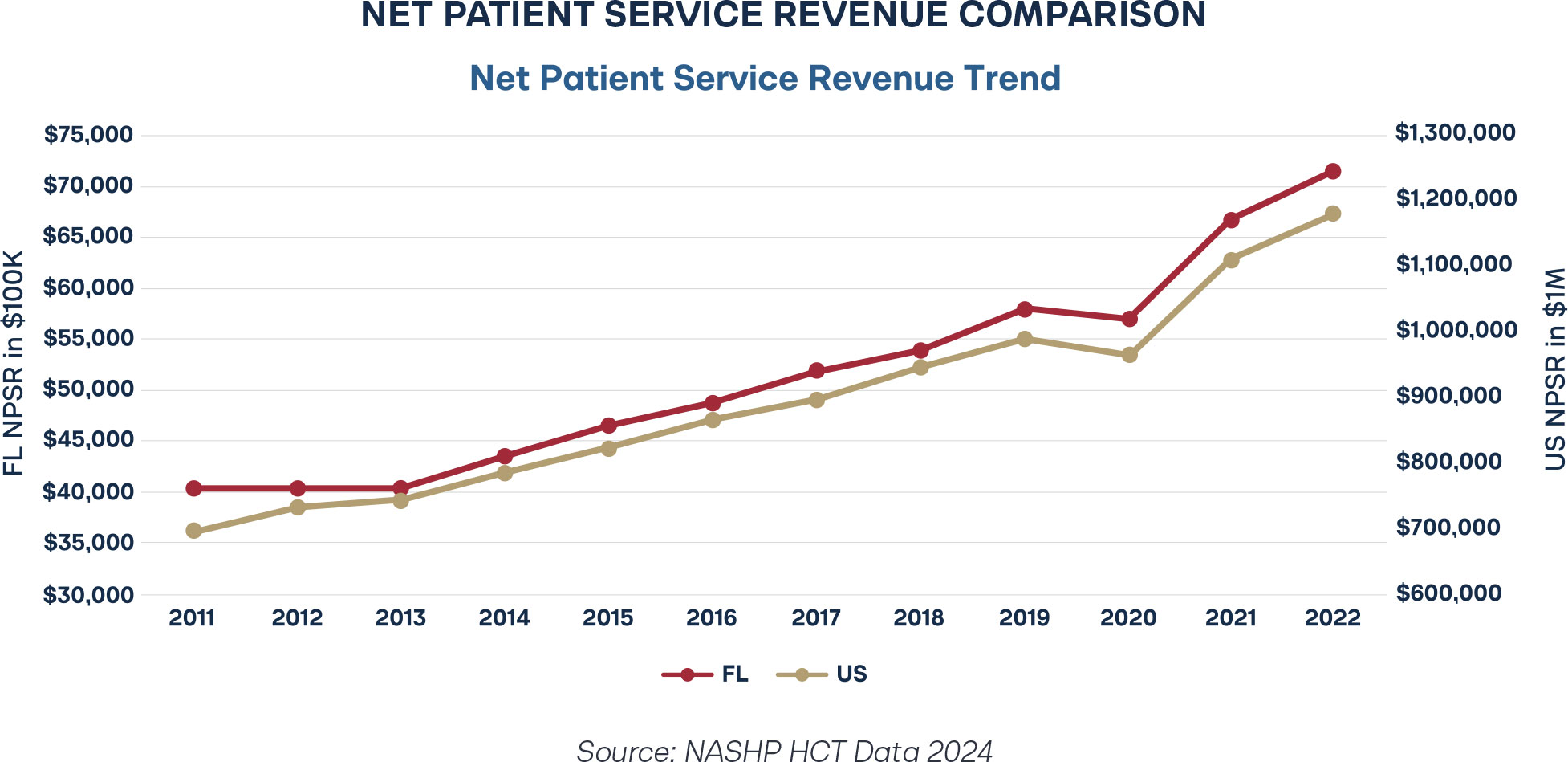

Florida repealed CON for Class I hospitals in 2019 and Class II hospitals in 2021. Net patient service revenue represents a hospital’s profit after accounting for Medicaid discounts, charity care, and bad debt. It is clear that, even after the repeal and despite the pandemic-induced dip in 2020, Florida hospital revenue is trending upward, on par with and surpassing overall U.S. trends.

Health Outcomes

As a natural result of weakened access to healthcare, individuals’ health deteriorates because medical needs go unmet. Poorer health becomes a communal experience, and individuals suffer unnecessarily. Lamentably, disparity of care between demographics also sharpens, with those most in need of medical attention sidelined, sometimes with irreversible effects. Empirical evidence suggests some subgroups most severely impacted by CON laws are individuals needing behavioral health services, expectant mothers, patients seeking diagnosis, and individuals wrestling with heart health problems. The following sections provide a detailed breakdown of research in each of these thematic groups.

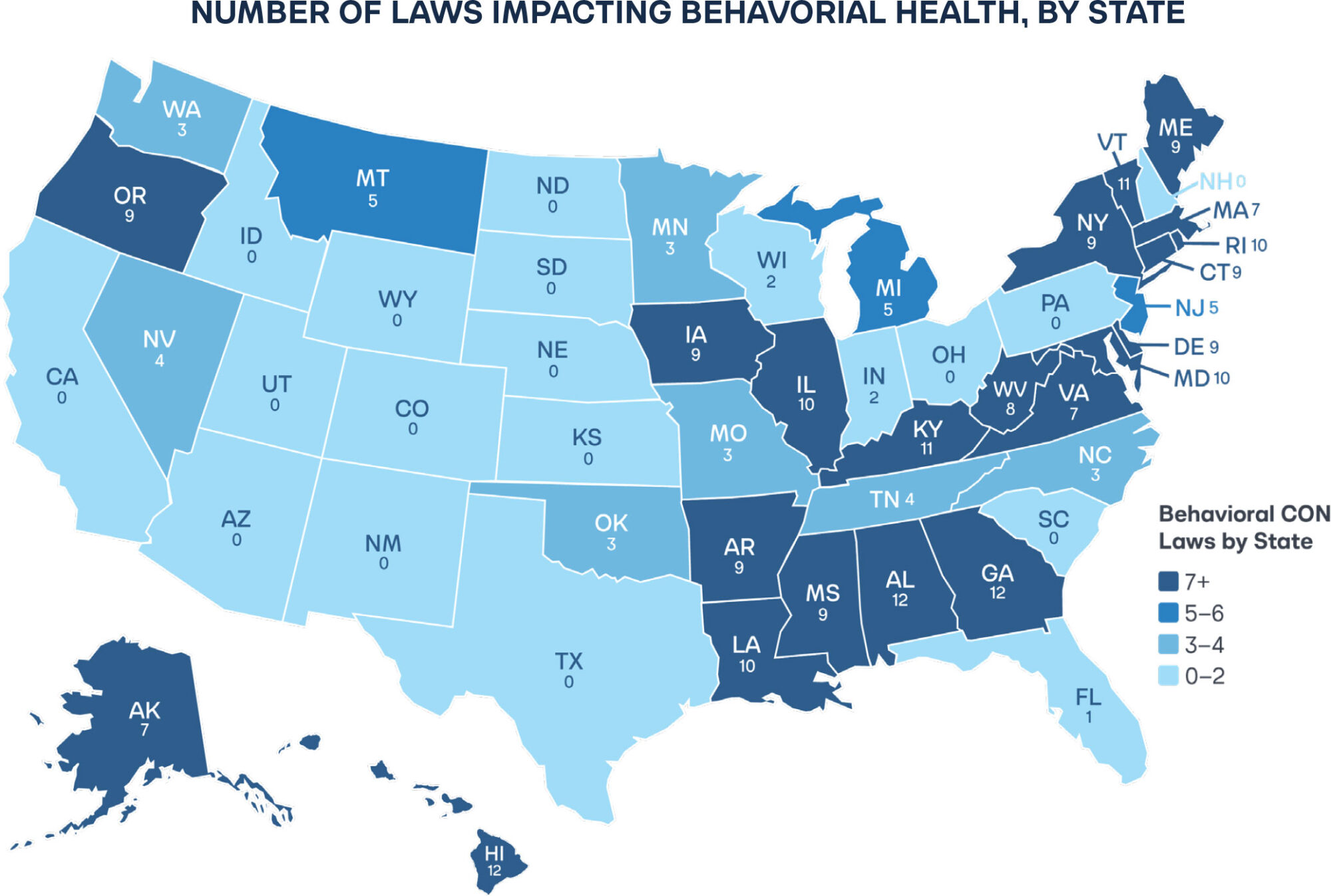

Behavioral Health: Crisis of Constrained Access

CON laws have produced deeply harmful effects in behavioral health, a sector already facing chronic shortages and rising demand. Behavioral health encompasses everything from psychiatric care to substance use disorder treatments and services for people with developmental disabilities. The United States faces a deepening behavioral health crisis. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for young individuals between the ages of 10 and 34.26 The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) most recent survey found that 16.8 percent of individuals over 12 had a substance abuse disorder in the past year, with substance abuse for drugs increasing since the last survey.27 For individuals with developmental disabilities, nearly 60 percent have co-occurring mental health conditions.28

By restricting the creation or expansion of psychiatric hospitals, beds, inpatient and residential treatment facilities, chemical dependency centers, crisis stabilization units, psychiatric services, and more, CON laws constrain access to care for patients struggling with substance abuse and mental health. The laws limit the ability of private providers to meet urgent community needs.

One study confirms the scale of this impact. States enforcing CON laws for behavioral health have 20 percent fewer psychiatric hospitals per million residents and 56 percent fewer inpatient psychiatric clients per 10 thousand residents compared to states without such restrictions.29 The same study also found that facilities in these states are 5.3 percentage points less likely to accept Medicare patients. Instead of improving efficiency, CON regimes in psychiatric healthcare reduce the number of treatment options, prolong wait times, and deepen shortages of inpatient beds across the country.

A 2022 study examined the nationwide effects of substance abuse disorder-specific CON regulations and found that, although the overall number of facilities, beds, and clients did not change significantly, states enforcing these laws saw a six-percent decline in the share of treatment centers accepting private insurance. Even after accounting for economic and demographic differences, that reduction persisted.30

CON barriers narrow the treatment ecosystem and create financial burdens for families seeking help. In fact, state CON laws for substance use disorder (SUD) treatment facilities are associated with increases in the number of infants born with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome and higher rates of emergency department visits.31

By discouraging private investment and complicating entry for new providers, CON laws reduce the diversity of care options and perpetuate the gaps that define America’s behavioral health crisis. Repealing or reforming these restrictions would help open the market, attract private providers, and improve access to mental health and addiction treatment for patients across all income levels.

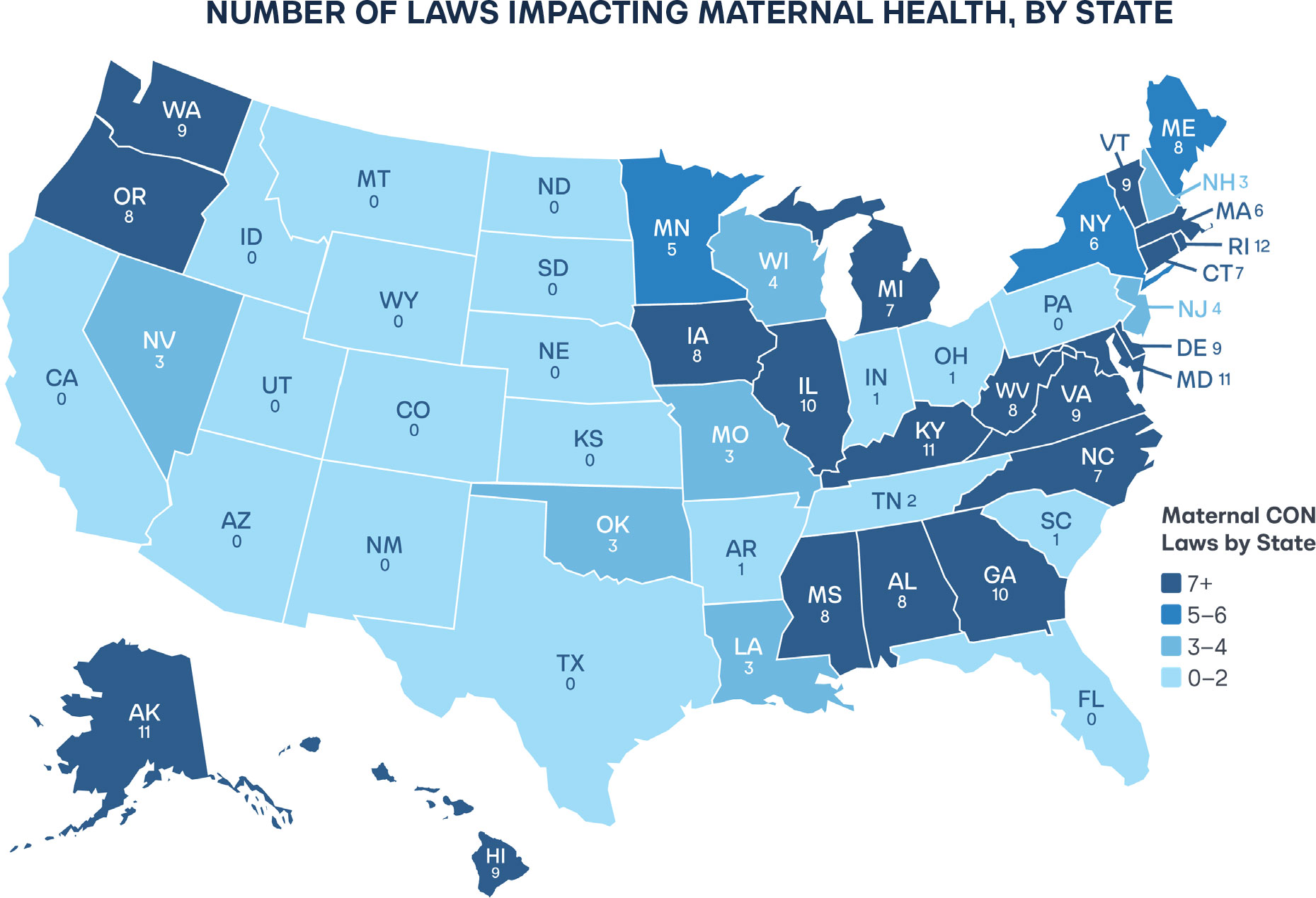

Maternal and Infant Health: Crisis in Critical Care

Nearly 35 percent of all United States counties are considered maternal health deserts, with 5.6 million women residing in areas with limited access, according to the March of Dimes.32 Forty percent of all women in rural areas live about 40 minutes away from a birthing hospital.33 United States infant mortality stands at 5.12 deaths per 1,000 births. However, in some particularly rural states, the situation is even more dire. Mississippi recently declared a public health crisis: its infant mortality rates increased to 9.7 deaths per 1,000 births in 2024.34

Despite the harrowing statistics, many states still restrict the number of labor and delivery beds at hospitals, neonatal intensive care units, neonatal intensive care beds, obstetric services and facilities, pediatrics, birthing centers, and ultrasound equipment—all of which directly affect mothers. Though less than half of all rural hospitals offer labor and delivery services, 10 percent of all rural labor and delivery services have closed since 2020.35 With already few options as a result of CON laws, any labor and delivery unit shutting down can be devastating to a community.

Certificate of Need (CON) laws worsen maternal health outcomes in the United States by restricting access to essential prenatal and obstetric care. Arguably, it is one of the most damaging barriers to maternal well-being. By requiring state approval before hospitals or clinics can expand maternity wards, open birthing centers, or purchase ultrasound and neonatal equipment, CON laws effectively freeze competition in the very markets where innovation and capacity are most needed.

For example, before South Carolina largely repealed CON services, one incumbent hospital near the coast spent years fighting another hospital to keep them from starting a new NICU unit.36

Mothers and infants in states that maintain CON laws experience eight percent higher rates of inadequate prenatal care compared to those that do not.37 This reflects the predictable consequence of government-imposed scarcity. Fewer options reach expectant mothers, particularly in rural or low-income communities.

The patterns are consistent: maternal deserts expand where regulatory barriers persist. As long as these outdated laws remain in place, more mothers will forgo critical prenatal visits, and more families will face unnecessary risk in childbirth. Modern maternal healthcare requires flexibility, competition, and patient choice, conditions that flourish in markets free from political gatekeeping.

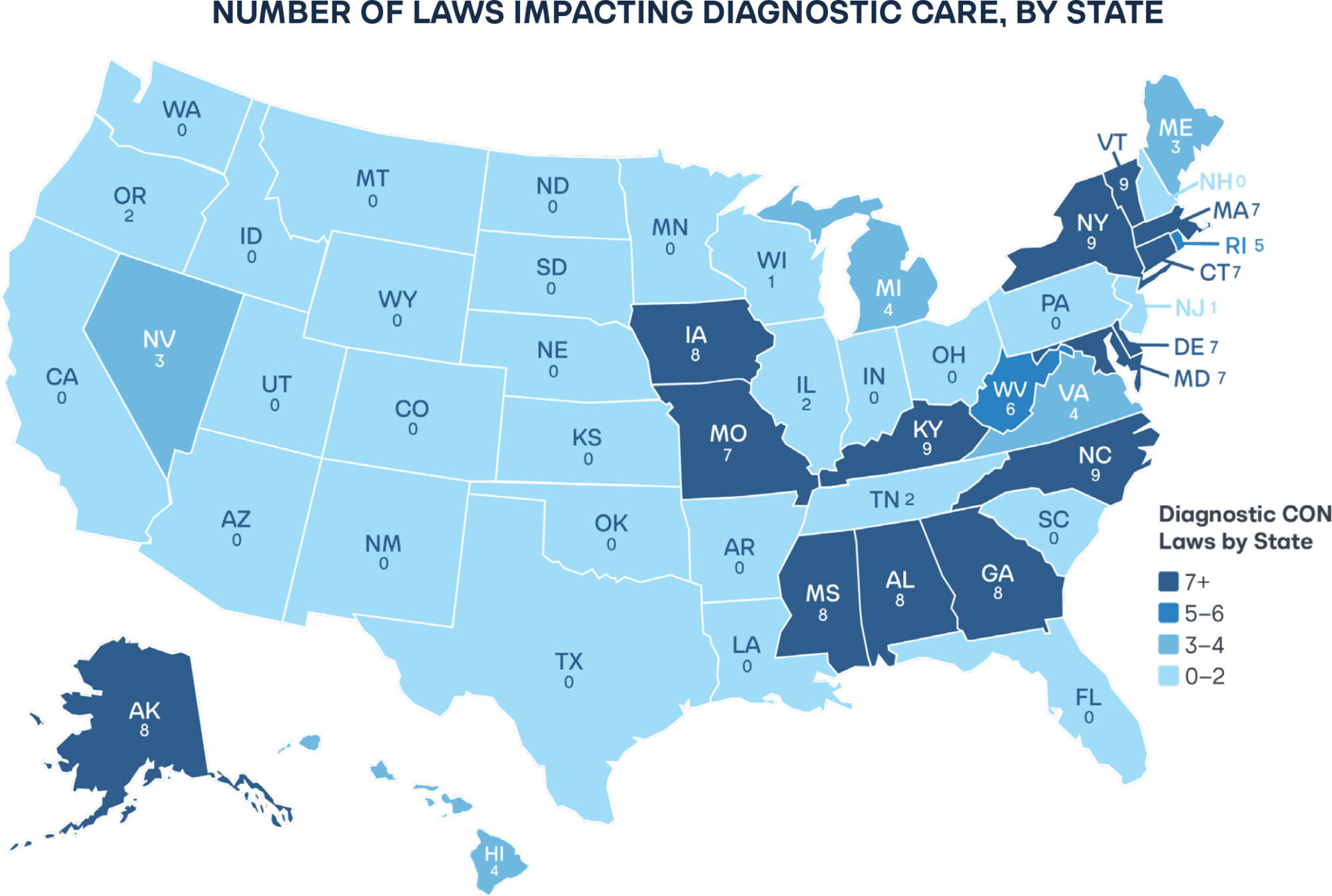

Diagnosis: Crisis of Bottlenecks

When a business needs equipment to offer services, it can typically purchase it without government interference. However, healthcare providers in some CON states are required to obtain permission before purchasing many types of diagnostic and therapeutic equipment, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines, positron emission tomography (PET), or other types of diagnostic equipment. Sometimes, independent diagnostic centers are also subject to CON restrictions.

In a study of Medicare claims that measured the impact of CON laws on both the quantity and quality of imaging (including CT and MRI scans), scholars found that states with CON oversight deliver fewer imaging services overall, with the decline concentrated in “low-value” imaging: tests that offer little or no clinical benefit. “High-value” imaging, which is essential for accurate diagnosis and treatment, remained largely unchanged. The authors describe this as a “generally salutary effect,” suggesting that CON implementation appears to reduce unnecessary scans without curbing essential ones.38

However, measured efficiency comes at a cost. The same regulations that limit low-value use constrain technological diffusion and private investment in diagnostic capacity. The study documents that MRI facilities are about 14 percent less likely to operate in CON-regulated areas, underscoring how regulatory barriers shape not only utilization but geographic access. For patients, particularly those in rural regions, this means longer travel distances, longer wait times, and fewer treatment options. Repealing or modernizing these restrictions would preserve incentives for appropriate imaging while allowing market competition to expand access and accelerate adoption of new technology.

CON law repeals are associated with a reduction of 2,499 lung cancer deaths a year.39 Given the importance of early diagnostic care for cancer patients, delays in diagnostic care can have fatal consequences.

Heart Health: Crisis of Lethal Delay

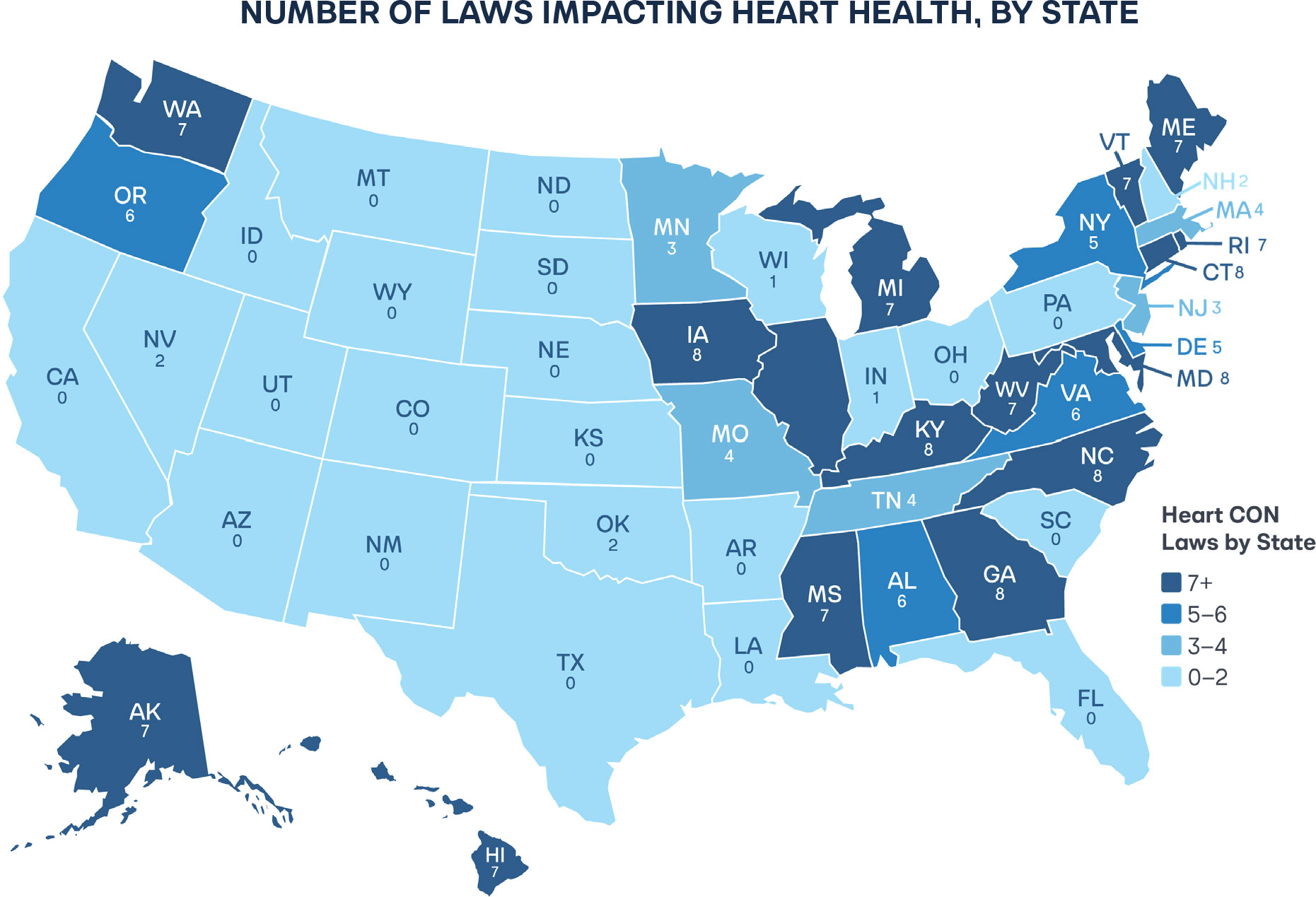

Certificate of Need regulations have contributed directly to higher rates of heart attack mortality and worse cardiac outcomes in the United States. States implementing or maintaining CON regulations experience six to 10 percent higher heart-attack death rates within three years of enactment.40 Heart health CON regulations can limit when and where hospitals may add cardiac surgery programs, provide open heart surgery, or purchase specialized equipment.

The empirical evidence is stark. One economist found that CON restrictions concentrate heart procedures in fewer hospitals and yield no measurable improvement in mortality.41 Additionally, the concentration of cardiac services under CON regimes often results in longer travel distances and higher patient volumes at fewer facilities. It diminishes the flexibility of hospitals to respond to local cardiac emergencies. Far from improving efficiency, the result is reduced access when seconds and minutes determine survival.

Additional research has quantified that cost in lives. A border-county analysis isolated the effect of CON by comparing similar populations on either side of state CON boundaries, confirming that it is the regulation itself, not demographic variation, driving excess deaths.42 Disparities in heart health care outcomes between black and white demographics dissipate when CON review is repealed for heart-related services.43 Repeal will expand cardiac care capacity, shorten emergency response times, and save lives each year.

Innovation

Although it is difficult to obtain a true measure of CON’s chilling effect on new providers, the laws certainly hinder the emergence of innovation in a more natural regulatory environment. Bright minds with new ideas logically turn to states with easier pathways to providing new services. Some states, such as Alabama and Georgia, have blanket laws that require a CON application for any new service.44 This means that if a groundbreaking new healthcare service were to be developed, states without CON would likely implement the services first, and states with CON laws but without the “any new services” clauses would follow afterward. But states with blanket CON requirements for any new services would likely implement the new services dead last. For developing companies, early-stage resources are often scarce, and they seek states where investment opportunities are clear and well-defined. Requiring an application for any new service translates to lost jobs and delays in access to groundbreaking discoveries.

One author writes, “Not only are motivated new practitioners not able to bring their ideas to patients, but current practitioners have little motivation to create anything new themselves. Competition provides one of the main driving forces behind innovation.”45 CON laws handcuff creative medical experts from providing highly needed out-of-the-box solutions. Although challenging to measure, the same author describes a scenario of a man who sought to provide a new service in Virginia that assists with early diagnosis of one of the leading causes of cancer deaths; unfortunately, he never had the chance to give Virginians the same access to this service as residents of other states, because the Commonwealth of Virginia denied him a CON.46 This anecdote, along with others, illustrates that unfettered innovation in the medical field would undoubtedly support improved health outcomes for individuals and families.

Methodology

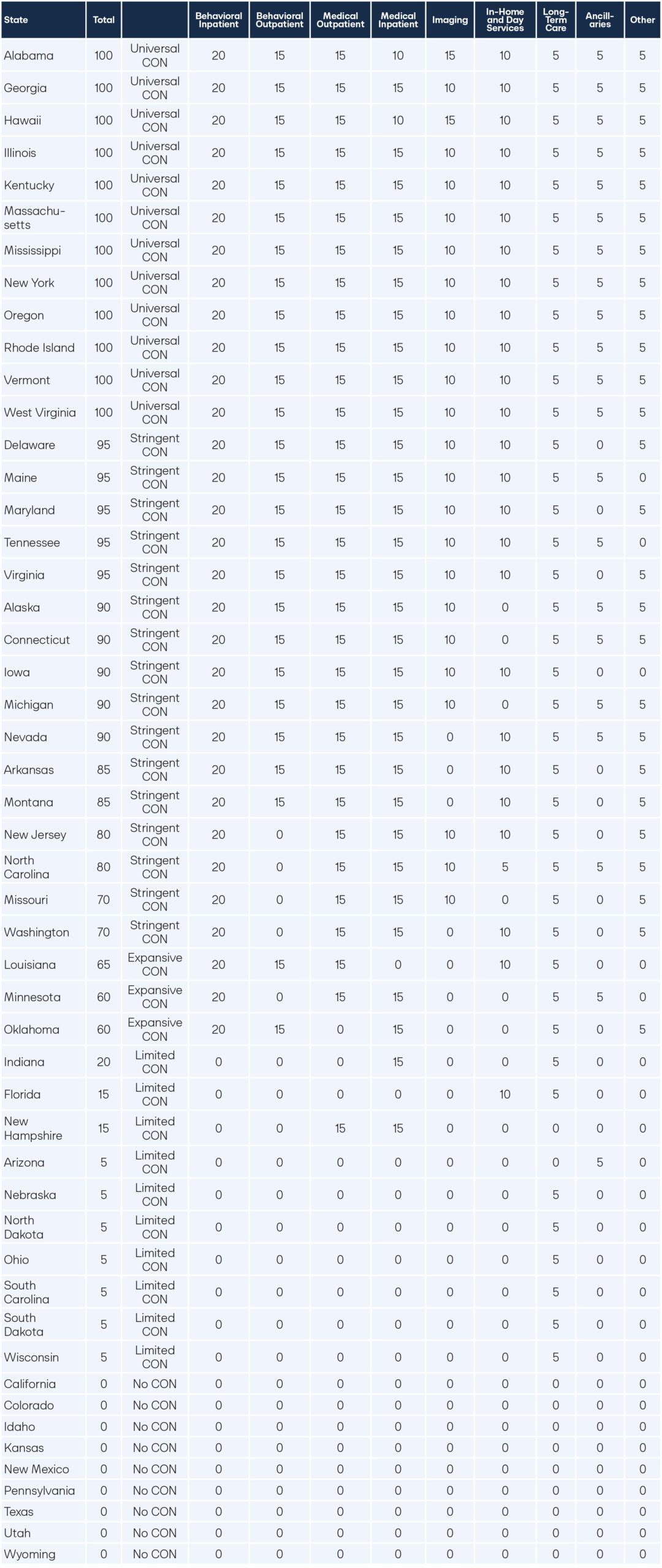

This research provides a legislative taxonomy that scores every state on Certificate of Need (CON) in several categories: Behavioral Outpatient, Behavioral Inpatient, Medical Outpatient, Medical Inpatient, Imaging, In-Home and Day Services, Long-Term Care, Ancillaries, and Other.

Some states will require a CON for facilities, others for beds, while some focus on equipment, services, or any combination thereof. For this analysis, any CON restriction that falls under any of the categories will be included. For example, many states require a CON for the establishment of a psychiatric hospital facility and a CON for the number of beds operated by that facility. If a state regulates both, it would need to repeal both types of CON to improve its score on the behavioral inpatient category in future years. Further, a state may regulate dialysis clinics in areas such as the establishment of facilities, the purchase of dialysis equipment, the provision of dialysis services, or even the number of beds (or chairs) at a dialysis facility. To improve a score under Medical Outpatient, a state would need to repeal all CON regulations related to dialysis and for every other related item listed in the Medical Outpatient category.

To build the state citation dataset used to create the overall scoring, the authors first built upon the work of the Institute for Justice, which tracked CON laws for facilities, beds, equipment, and services by consolidating the separate state analyses into a single dataset.47 The matrix then broadened the dataset to screen whether each state required a CON for 109 types of services, facilities, bed-types, equipment, and other unique CON laws. For a full list of the CON laws included in the state citation dataset, see Appendix 1.0. Additionally, the dataset accounted for legislative changes through 2025 and screened whether states had CON programs by another name. For example, New Hampshire’s material adverse impact policy functions under a similar intent and outcome as its previous CON laws.

Additionally, Nevada does not refer to its program as a CON. However, the state code still requires a secretary to approve whether a new healthcare facility can be built in a rural area. Finally, using a large-language-model (LLM) API, we scanned each row’s cited statutes to flag entries that appear unverified, either because the text and facility definitions are inconsistent or because a related controlling provision is missing; in such cases, the model surfaces the probable statute to cite. After this screening, all flagged rows are manually re-verified against the underlying code.

Some states may define similar facilities or services differently. For example, long-term care can encompass various definitions, including rehabilitation facilities, residential care facilities, nursing homes, skilled nursing facilities, adult care facilities, continuing care, and other similar settings. The analysis accounted for differences in state definitions when determining whether to count a facility or service under one of the categories listed below. However, some ambiguity exists in the implementation of these definitions. For state-specific legislative analysis, raw data, and lists of relevant items regulated by CON tied to the citations in state code, see Appendix 2.0.

A. Behavioral Outpatient (20 points)

Any state with CON restrictions on outpatient facilities for behavioral health, including but not limited to:

- Nonresidential, substance-based treatment centers for opiate addiction

- Community mental health centers

- Alcohol and drug abuse centers

- Chemical dependency services

B. Behavioral Inpatient (15 points)

15 points assigned for states with CON restrictions on behavioral inpatient facilities, including but not limited to:

- Psychiatric hospitals

- Residential psychiatric treatment centers

- Hospitals and intermediate care facilities for individuals with substance abuse

- Sanitariums

C. Medical Outpatient (15 points)

Any state with CON restrictions on any of the following was assigned 15 points in the medical outpatient category, including but not limited to:

C.1 General outpatient surgery and outpatient clinics

- Ambulatory surgical facilities or centers

- Outpatient surgical facilities

- Urgent cares, outpatient clinics

C.2. Treatment Centers, Diagnostic Centers, and Related Services:

- Kidney disease centers, hemodialysis services/facilities/units, lithotripsy

- Radiation treatment centers

- Free-standing cancer treatment centers

- Heart service centers, cardiac catheterization

- Radiation therapy, including but not limited to stereotactic radiotherapy and radiosurgery, proton beam therapy, and megavoltage radiation therapy

- Burn care

- Any other specialized centers, clinics, or physicians’ offices developed for the provision of specialized medical services

C.3. Outpatient Rehabilitation Centers and Maternal and Infant Care:

- Outpatient rehabilitation centers

- Birthing centers

- Obstetric services or facilities

- Pediatric services or facilities

D. Medical Inpatient (10 points)

Any state with CON restrictions on any of the following was assigned 10 points of restriction in the medical inpatient category, including but not limited to:

D.1 Hospitals and hospital beds

- General hospitals

- Specialized hospitals

- Children’s hospitals

- Tuberculosis hospitals

- Cancer hospitals

- Long-term care hospitals

- Maternity hospitals

- Chronic disease hospitals

- Neonatal intensive care

- Hospitals or other facilities or institutions operated by the state that provide services eligible for Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement

D.2. Services

- Post-acute head injury retraining facilities

- Free-standing emergency centers, surgical centers, or departments

- Organ transplants

- Open heart surgery

- Neurosurgery

E. Imaging (15 points)

15 points assigned to any state with restrictions on imaging tools and facilities, including but not limited to:

- Diagnostic testing centers

- Computed tomographic (CT) scanning

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Magnetic source imaging (MSI)

- Nuclear medicine imaging, including positron emission tomographic (PET) scanning

F. In-Home and Day Services (10 points)

10 points assigned to states with restrictions on any of the following with In-Home or Day Services, including but not limited to:

F.1 In-Home Services

- Home nursing-care providers or home health agencies

- Home care providers

- Hospice care and hospice providers

F.2 Day Services

- Adult day health care programs

- Developmentally disabled centers

- Pediatric day care facilities

G. Long-term Care (5 points)

Any state restricting any of the following was assigned 5 points for long-term care services or facilities, including but not limited to:

- Long-term care facilities

- Nursing homes

- Intermediate care facilities

- Skilled nursing facilities

- Assisted living facilities

- Residential care facilities

- Rest homes

- Residential care homes

- Personal care homes

- Family care homes

- Continual care community and other non-traditional, long-term care facilities

- Adult care facilities

- Facilities for individuals with developmental disabilities

- Developmental disability centers or intellectual disability centers

H. Ancillaries (5 points)

5 points assigned to any state with CON restrictions on ancillaries, including but not limited to:

- Laboratories, including clinical and bioanalytical

- Central service facilities

- Health maintenance organizations

- Ambulatory services

I. Other (5 points)

5 points assigned in this general “other” category for restrictions on small facilities that do not easily fall into the other categories, such as:

- Health facility established by a health maintenance organization

- Requirement for a transfer of ownership, for parent companies, subsidiaries, affiliates, or joint ventures

- Discontinuation of services

- Renovations

- New facility expenditures

State Scores

TABLE 1: State CON Scores, Listed Alphabetically

TABLE 2: State CON Scores, Listed by Restrictiveness

Limitations and Disclaimer

The findings and data presented in this whitepaper, particularly the 50-state survey of Certificate of Need (CON) restrictions, represent the culmination of substantial research and good-faith efforts by the Cicero Institute to accurately assess the current legislative and regulatory landscape across the United States.

However, due to the inherent complexity and decentralized nature of CON policy, the Institute recognizes several limitations:

Variation in Statutes and Regulations: CON laws vary significantly across states, including the nomenclature for similar facilities or services and the scope of regulatory oversight. Exemptions are sometimes explicitly stated in state code or implicitly defined in state code definitions of healthcare facilities; however, other items are more ambiguous, as state CON boards appear to have discretion over whether a specific item merits an exemption. More transparency from CON boards is needed to fully capture all services, facilities, and equipment regulated by CON in a state. This heterogeneity makes it challenging to achieve a perfectly uniform categorization.

Depth and Breadth of Policy: Given the extensive depth and breadth of these policies, and their frequent integration into state administrative code, inconsistencies in implementation and nuances exist that may not be fully discernible through statutory review alone.

Dynamic Legal Environment: The legislative and regulatory environment governing CON is subject to constant change through new statutes, administrative rule amendments, and judicial interpretations. The data presented reflects the state of the law as of the date of publication, but this information may be superseded by subsequent action.

While every effort has been made to accurately capture and categorize the CON restrictions for facility, equipment, bed, and service types within each state, the Cicero Institute cannot guarantee with 100 percent certainty that every applicable item has been captured or categorized without error.

Therefore, this report is provided for informational and analytical purposes only. Third parties relying on this survey and analysis should supplement this report with their own independent, detailed legal and regulatory research tailored to their specific state and operational interests, including interviews with state CON boards, analysis of application denials, and analysis of which services, facilities, beds, and equipment types do not bother to apply. The Cicero Institute expressly disclaims any liability for errors or omissions arising from the complex nature of the data collected.

Repeal Strategies

Some states have attempted to reform certificate of need (CON) laws by selecting one or more CONs, such as those governing new hospital beds or the construction of new facilities, to repeal, hoping it will sufficiently address the problem. Just as effective medical care involves complex and interlacing layers of facilities, hospital beds, services, and equipment, repeal of CON for just one of those aspects, leaving the others intact, cannot be expected to resolve systemic problems. Only a broad repeal of all remaining CON mandates will truly restore a healthy and responsive healthcare market.

While repealing one CON will not suffice, a strategy of successive repeals for specific services where evidence of harm is clearest is the best place to start, as a practical strategy toward full repeal in locations where bipartisan momentum has not reached critical mass. Such a sequence builds powerful political will, demonstrates success, and weakens entrenched opposition over time. In the short term, prioritizing the repeal of CONs that affect maternal health, heart care, behavioral health, and diagnostic services will yield relief quickly for residents and highlight the human cost of bureaucratic delay. These sectors together account for a large share of the most life-sensitive and capacity-limited services in the nation’s healthcare system. The following subsections summarize our findings in each of these four health areas and outline why repeal of their associated CONs should be prioritized.

Rural Health Transformation Fund

The Rural Health Transformation Program (RHTP) is a federal initiative, managed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), established to provide $50 billion in funding to states over five years to strengthen rural communities across America. $25 billion will be provided to all states that applied to the program as baseline funding. The second $25 billion will be given to states based on two measures: rural factors data and technical score factors.48 States cannot alter the funding based on rural data and baseline factors. Still, the technical score factors can be thought of as the “competitive” portion of the Rural Health Transformation Program.

If states have a high technical score, they can receive a higher amount of funding from the competitive portion of the $50 billion fund. For the technical score factors, CMS highlighted a handful of key state policies that states can signal they plan to reform in their applications. One such policy was certificate of need (CON). States can improve their CON scores by targeting reforms based on the methodology outlined in this report.

Complete repeal of CON would result in the best possible score for the RHTP and maximize the amount of funding that states can receive. However, full repeal might not be possible in every political context. Therefore, targeted repeals based on the methodology of this report would help improve scores. For example, a state could improve its CON score by a full 35 points by targeting all inpatient and outpatient behavioral health beds, services, and facilities covered by CON in its state. For a state-specific legislative analysis, and for lists of relevant items regulated by CON tied to the citations in state code, see Appendix 2.0.

State Strategy

Behavioral Health

Behavioral health services, including psychiatric hospitals, addiction recovery centers, and community mental health centers, are constrained by 12 CONs across the states. These restrictions limit the ability of private providers to meet urgent community needs, prolong wait times, and deepen shortages of inpatient and residential treatment options. States enforcing CON laws on behavioral health have 20 percent fewer psychiatric hospitals per million residents and 56 percent fewer inpatient psychiatric clients per ten thousand residents than states without them—evidence of how deeply these policies constrain care.49 Repealing these laws would immediately enable expansion of inpatient and outpatient facilities, ease emergency department overcrowding, and improve continuity of care for individuals in crisis. Repeal in this domain can also yield visible, bipartisan wins by addressing a widely acknowledged public health emergency.

Maternal Health

Across the United States, our analysis identified 12 separate CONs directly affecting maternal and infant health services, including obstetric beds, neonatal intensive care units, birthing centers, and related facilities. States imposing these requirements restrict the ability of hospitals and independent providers to expand maternal care capacity, particularly in rural or low-income regions. These CONs are harmful in any state, but especially in those where maternal mortality rates are already among the nation’s highest. Eliminating CONs related to maternal health would permit more flexible expansion of maternity wards, encourage the creation of community-based birthing centers, and alleviate severe provider shortages that disproportionately harm women of color and rural mothers. With nearly 35 percent of U.S. counties classified as maternal health deserts50 and mothers in CON states experiencing eight percent higher rates of inadequate prenatal care51, the evidence is clear: CON laws deepen the maternal care crisis by cutting off access where it is needed most.

Diagnostic Services

Diagnostic services are subject to nine CONs, covering technologies such as MRI, CT, and PET scanners, as well as dedicated facilities like independent diagnostic centers. These requirements limit patient access to essential imaging and diagnostic testing, suppress market entry for mobile diagnostic units, and contribute to higher costs and longer wait times for patients seeking early detection. Eliminating these CONs would accelerate the adoption of advanced diagnostic tools, promote early intervention in diseases such as cancer and stroke (when timing is critical), and empower community-level clinics to offer modern diagnostic capacity without costly regulatory delays. Research shows that MRI facilities are 14 percent less likely to operate in CON-regulated states52, and repealing these laws is associated with 2,499 fewer lung cancer deaths each year.53 Evidence that delayed diagnostics under CON regimes come at a measurable human cost.

Heart Health

In the field of cardiovascular care and heart health, eight CONs govern related healthcare; this includes the establishment of catheterization services, cardiac surgery equipment, providing open heart surgery, and organ transplants (in addition to related diagnostic equipment such as CT or MRI machines used in cardiac imaging). Residents in states with multiple cardiac-care CONs likely face longer average travel distances to treatment centers and delayed access to time-sensitive interventions. Removing these CONs would foster competition, increase access to timely cardiac procedures, and reduce mortality from acute cardiac events. Empirical evidence shows that states maintaining heart-health CON laws experience six to 10 percent higher heart-attack death rates within three years of enactment54, a pattern the study isolated by border-county research. Additionally, disparities in heart health care outcomes between black and white demographics dissipate when CON review is repealed for heart-related services.55 Repeal would expand cardiac care capacity, shorten emergency response times, and save lives each year.

Coalitions

Building strong coalitions with existing thought leaders, patient advocates, and grassroots organizations around these four areas of reform will accelerate progress toward CON repeal. Broadly, this includes patients’ rights advocates and past CON applicants who were denied approval. Within each specific health area, natural allies include cancer advocacy groups and diagnostic imaging providers for diagnostic care reform; maternal and infant health organizations and parent networks for maternal care reforms; addiction recovery and mental health coalitions for behavioral health reforms; and heart health foundations and cardiovascular associations for cardiac care reforms.

New Hampshire: A Cautionary Example

Though most states will use the term “certificate of need,” other states use alternative terms in the state code for the same process. For example, Louisiana refers to it as “facility need review,” and Arkansas calls it “permit of approval.” In Nevada, there is no formal name other than the text in the state code that requires facilities in certain counties to obtain approval from the state Director of Public and Behavioral Health for any capital expenditures or the opening of new facilities.56 In New Hampshire, the state instituted a policy that looks much different than typical CON, but the operational impact and intent remain the same.

When New Hampshire repealed their CON laws in 2016, many thought the laws were off the books for good. But New Hampshire had actually swapped the laws to a notice requirement paired with a “material adverse impact” policy, which shifted the power held by third-party CON boards directly to local critical access hospitals. The policy required new facilities to provide notice to a critical access hospital if they intended to open within 15 miles of the hospital. Though a 15-mile radius may sound modest, the requirement encompasses the majority of the state.57 Twenty-five different types of facilities are required to provide notice to the critical access hospitals. For six of those facility types, if the critical access hospital can claim that the opening of the service may result in a material adverse impact, the facility can no longer continue to apply for licensure.

New Hampshire state law defines material adverse impact as, “granting the application would more likely than not tangibly minimize the critical access hospital’s ability to continue providing the health care services.” Anything from market share, utilization, patient charges, referral sources, or personnel resources can be claimed under material adverse impact. Though a facility may appeal a decision, a critical access hospital can counter-appeal every appeal. Notably, New Hampshire has 31 ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs). Every ASC, except one, resides outside the 15-mile radius of critical access hospitals, underscoring the market influence held by the material adverse impact rule. In June of 2025, New Hampshire removed the material adverse impact notification policy for all medical outpatient services through HB 2.58 However, the requirement remains for all new hospitals.

The material adverse impact scheme in New Hampshire illustrates that CON laws can assume new forms after repeal. Once repeal is achieved, advocates should vigilantly ensure that CON laws do not reappear under a new guise or in a different name.

Conclusion

For nearly half a century, Certificate of Need laws have persisted as a structural barrier to affordable, accessible, and innovative healthcare in the United States. Conceived to curb wasteful spending under an obsolete reimbursement model, these laws and their subsequent regulations have instead entrenched inefficiency, stifled innovation, and restricted patient choice. The evidence is overwhelming: CON laws drive up costs, limit access, worsen health outcomes, and suppress the competitive dynamics essential to responsive care.

As detailed in our state-by-state rankings, these harms manifest most acutely in states with expansive CON regimes. These states face higher maternal mortality rates, longer cardiac response times, fewer mental health facilities, and diminished access to diagnostic imaging. Restrictions inherent to CON laws and regulations impose costs that are not only measured in dollars, but also in the lives of loved ones who are delayed, displaced, or lost.

Full repeal of all remaining CON laws should be the clear objective of every state seeking to strengthen its healthcare system. As long as government permission stands between patients and providers, innovation and access will remain captive to bureaucracy and incumbent interests. However, in states where full repeal remains politically challenging, phased repeal over several years, beginning with the most life-sensitive and demonstrably harmful categories, offers a pragmatic path forward. Starting with targeted reforms—prioritizing maternal, behavioral, diagnostic, and cardiac care—can leverage coalitions of advocates and align with Federal incentives, such as the Rural Health Transformation Fund, to build public trust, demonstrate success, and create the political momentum necessary for full repeal.

By utilizing the scoring and strategies outlined in this playbook, comparing the restrictiveness of each state’s regulatory environment, policymakers, advocates, and citizens will gain a comprehensive view of the scope of CON, and prioritize reforms where the need is most pressing.

The path to a more affordable and innovative healthcare system does not lie in preserving obsolete permission regimes, but in restoring the principle that providers should be free to serve, and patients free to choose, without unnecessary government interference. Whether through comprehensive repeal or targeted, incremental steps, the imperative for 2026 and beyond remains clear: dismantle these barriers to deliver the care Americans deserve.

Appendix

Appendix 1.0

Note: While the dataset is intended to encompass everything possible, CON laws are notoriously broad. The list above still does not cover every possible type of service, facility, equipment, bed, or other item regulated by CON, especially when clauses such as “any new service” exist in the state code.

Appendix 2.0

State-by-State Scoring Sheet Analysis of Certificate of Need

The complete data set, including raw data of the state-by-state analysis tied to legislative statutes and administrative code, is available via the online Google Sheet at:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1z3EXK7Li4OATqfWyl6Upo8fRty6FA7uUbeVW5fKYBEw/edit?gid=1962736597#gid=1962736597

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about our fight for policies at the state level that restore liberty through transparency and accountability in American governance.