The Evolution of the American Dream

Examining past Americans’ standards of living gives a fresh perspective on where we are today, how far we have come, and where we can go from here. If we continue to cherish an entrepreneurial spirit and the competition of free ideas, America’s future contains unlimited possibilities.

Americans have long valued opportunity, prosperity, and success. These principles drive our national ethos, the “American Dream”—a term that symbolizes the pursuit of happiness and continued striving for a freer society, with future generations being on the whole more prosperous than those that came before.

Though we have always faced terrible challenges, American history shows that this dream has been—and continues to be—a success. Examining past Americans’ standards of living gives a fresh perspective on where we are today, how far we have come, and where we can go from here. If we continue to cherish an entrepreneurial spirit and the competition of free ideas, America’s future contains unlimited possibilities.

Racial minorities suffered greatly, urban life was miserable for the poor, and transatlantic immigratory conditions were horrific.

The Atlantic slave trade was abolished in 1808, but American slavery was entering its most conspicious period in national history, with 16 percent of our total population and 85 percent of all blacks living in slavery in 1820. Native Americans were not yet considered American citizens and were likely to be living in virtual slavery or in a tribe which the federal government would soon move west of the Mississippi River.

European immigration turned from a trickle into a gush that lasted through the 1860s. Most of these immigrants crossed the Atlantic below-deck on packet ships, which carried people, mail, and other cargo. Steerage was a dark, crowded, and damp experience for these passengers. Conditions were unsanitary and the sea was rough, meaning that it was messy and foul-smelling below deck, and that rats, insects, and disease were common. The Steerage Act of 1819 somewhat improved the horrible conditions for immigrants onboard transatlantic ships, but nonetheless, many immigrants arrived sick or dying in the major port cities of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston. These immigrants (mostly Irish and German), however, were willing to suffer through such conditions in order to pursue the economic opportunity and religious and political freedoms that America promised.

Since municipalities were responsible for providing for the poor in their city, local governments discouraged poverty by punishing it. To enter a poorhouse, most states required a public confession swearing to a lack of worldly goods and a need for assistance. Temporarily unemployed, able-bodied men would come and go from these horrific, bare-bones facilities, but the permanent “inmates” usually included the city’s destitute alcoholic, aging, and mentally- or physically-disabled populations. One of the most notorious poorhouses was Tewksbury Almshouse in Massachusetts, where abuse from overseers was rampant, inmates all used the same bathwater though many had open sores, patients in the insane ward were left for days without food, and vermin ate holes in the heads of the sick.

The influx of immigrants into port cities meant that poorhouses were overcrowded and filthy: the poorhouse population in New York City tripled from 1800 to 1820, and more than a seventh of the city’s residents received public or private relief. The boom of unskilled laborers drove down wages for the working class and made finding work extremely difficult for the poor.

For non-city dwellers, the American diet remained dull. But the diet of America’s urban population began to diversify as dining out became an accessible experience.

While transportation was faster after the Industrial Revolution, it was still very slow by today’s standards. This meant that for New Englanders, it would be a rare treat to eat a grapefruit or an orange from Florida. Vegetables had to be eaten pickled during the winter months, and in rural areas, people continued to eat what was available locally, either from their own farms, or could be purchased in town. Spices other than salt remained a luxury, and preparing meals was still a lot of hard work—the ordinary mid- to lower-class American family still hunted, farmed, and preserved the majority of their own food.

Before the turn of the century, food was only served at inns and hotels. But while cities expanded along the seaboard, the distance between work and residence increased. More hungry customers stopped in at popular new oyster bars and taverns. Big-city hotels also began to open up, most notably Baltimore’s City Hotel (1826), Philadelphia’s United States Hotel (1827), Washington’s National Hotel (1827), and Boston’s Tremont Hotel (1829). These popular hotels had large dining rooms that served soup, meat, vegetables, and puddings. Menus were usually not printed, but recited by waiters. The influx of immigrants in cities also meant more diverse fare was offered, with French restaurants and European-style confectioner’s shops among the most popular new offerings.

Though many aspects of life remained hard, increased industrialization and economic development meant that the average American had access to new technologies and lower prices than before.

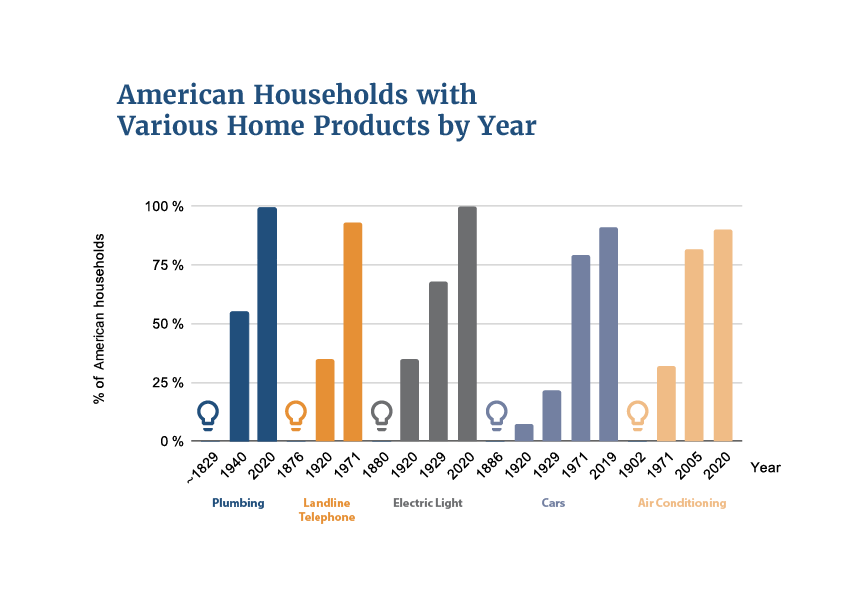

Electricity, plumbing, and heating as we now know them remained non-existent in 1820, and home heating was still either done with a brick fireplace, or with the cast-iron Franklin Stove, first invented in 1742. But in 1829, Boston’s Tremont Hotel became the first known American building with indoor plumbing, using water drawn from a rooftop metal storage tank that was fed by the newly-invented steam pump. This plumbing, however, was rudimentary at best, and modern plumbing would still take over a century to perfect.

Kicking off the American Industrial Revolution, in 1790 Samuel Slater introduced the first industrial cotton mill to the United States. By 1820, factories began to appear throughout New England, making it possible to perform work on a large scale in centralized locations, thereby increasing productivity and lowering the prices of many goods. A large majority of the new New England factory workers were young girls recruited from surrounding farms. These girls could be paid less than male workers, and in turn, they enjoyed a newfound independence from rural male-dominated households.

Construction began on New York’s Erie Canal in 1817, connecting the Eastern seaboard to the Old Northwest. This highly successful canal project set off a canal frenzy in the US: By 1840, over 3,000 miles of canal had been built, including a complete waterway from New York to New Orleans. Paired with the novel steamboat (first built by American inventor Robert Fulton in 1807), travel became faster and cheaper. Land travel had much improved over the last century as well: States began to charter privately-run turnpikes, which charged fees for use. New York was the leader in this arena, increasing its state roads from 1,000 miles in 1810 to 4,000 miles by 1820. Improvements in transportation, along with the new printing technologies of the century and the implementation of the United States Postal Service in 1775, made the mass-produced newspaper possible.

Racial minorities suffered greatly, urban life was miserable for the poor, and transatlantic immigratory conditions were horrific.

The Atlantic slave trade was abolished in 1808, but American slavery was entering its most conspicious period in national history, with 16 percent of our total population and 85 percent of all blacks living in slavery in 1820. Native Americans were not yet considered American citizens and were likely to be living in virtual slavery or in a tribe which the federal government would soon move west of the Mississippi River.

European immigration turned from a trickle into a gush that lasted through the 1860s. Most of these immigrants crossed the Atlantic below-deck on packet ships, which carried people, mail, and other cargo. Steerage was a dark, crowded, and damp experience for these passengers. Conditions were unsanitary and the sea was rough, meaning that it was messy and foul-smelling below deck, and that rats, insects, and disease were common. The Steerage Act of 1819 somewhat improved the horrible conditions for immigrants onboard transatlantic ships, but nonetheless, many immigrants arrived sick or dying in the major port cities of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston. These immigrants (mostly Irish and German), however, were willing to suffer through such conditions in order to pursue the economic opportunity and religious and political freedoms that America promised.

Since municipalities were responsible for providing for the poor in their city, local governments discouraged poverty by punishing it. To enter a poorhouse, most states required a public confession swearing to a lack of worldly goods and a need for assistance. Temporarily unemployed, able-bodied men would come and go from these horrific, bare-bones facilities, but the permanent “inmates” usually included the city’s destitute alcoholic, aging, and mentally- or physically-disabled populations. One of the most notorious poorhouses was Tewksbury Almshouse in Massachusetts, where abuse from overseers was rampant, inmates all used the same bathwater though many had open sores, patients in the insane ward were left for days without food, and vermin ate holes in the heads of the sick.

The influx of immigrants into port cities meant that poorhouses were overcrowded and filthy: the poorhouse population in New York City tripled from 1800 to 1820, and more than a seventh of the city’s residents received public or private relief. The boom of unskilled laborers drove down wages for the working class and made finding work extremely difficult for the poor.

For non-city dwellers, the American diet remained dull. But the diet of America’s urban population began to diversify as dining out became an accessible experience.

While transportation was faster after the Industrial Revolution, it was still very slow by today’s standards. This meant that for New Englanders, it would be a rare treat to eat a grapefruit or an orange from Florida. Vegetables had to be eaten pickled during the winter months, and in rural areas, people continued to eat what was available locally, either from their own farms, or could be purchased in town. Spices other than salt remained a luxury, and preparing meals was still a lot of hard work—the ordinary mid- to lower-class American family still hunted, farmed, and preserved the majority of their own food.

Before the turn of the century, food was only served at inns and hotels. But while cities expanded along the seaboard, the distance between work and residence increased. More hungry customers stopped in at popular new oyster bars and taverns. Big-city hotels also began to open up, most notably Baltimore’s City Hotel (1826), Philadelphia’s United States Hotel (1827), Washington’s National Hotel (1827), and Boston’s Tremont Hotel (1829). These popular hotels had large dining rooms that served soup, meat, vegetables, and puddings. Menus were usually not printed, but recited by waiters. The influx of immigrants in cities also meant more diverse fare was offered, with French restaurants and European-style confectioner’s shops among the most popular new offerings.

Though many aspects of life remained hard, increased industrialization and economic development meant that the average American had access to new technologies and lower prices than before.

Electricity, plumbing, and heating as we now know them remained non-existent in 1820, and home heating was still either done with a brick fireplace, or with the cast-iron Franklin Stove, first invented in 1742. But in 1829, Boston’s Tremont Hotel became the first known American building with indoor plumbing, using water drawn from a rooftop metal storage tank that was fed by the newly-invented steam pump. This plumbing, however, was rudimentary at best, and modern plumbing would still take over a century to perfect.

Kicking off the American Industrial Revolution, in 1790 Samuel Slater introduced the first industrial cotton mill to the United States. By 1820, factories began to appear throughout New England, making it possible to perform work on a large scale in centralized locations, thereby increasing productivity and lowering the prices of many goods. A large majority of the new New England factory workers were young girls recruited from surrounding farms. These girls could be paid less than male workers, and in turn, they enjoyed a newfound independence from rural male-dominated households.

Construction began on New York’s Erie Canal in 1817, connecting the Eastern seaboard to the Old Northwest. This highly successful canal project set off a canal frenzy in the US: By 1840, over 3,000 miles of canal had been built, including a complete waterway from New York to New Orleans. Paired with the novel steamboat (first built by American inventor Robert Fulton in 1807), travel became faster and cheaper. Land travel had much improved over the last century as well: States began to charter privately-run turnpikes, which charged fees for use. New York was the leader in this arena, increasing its state roads from 1,000 miles in 1810 to 4,000 miles by 1820. Improvements in transportation, along with the new printing technologies of the century and the implementation of the United States Postal Service in 1775, made the mass-produced newspaper possible.

Heating, plumbing, and electricity had all significantly improved over the last century as well. By 1920, Americans were no longer heating their homes with wood, but with coal, either through a coal-fired boiler in the basement that delivered steam to radiators in every room, or through riveted-steel coal furnaces that delivered heat by natural convection through ducts to the floors above.

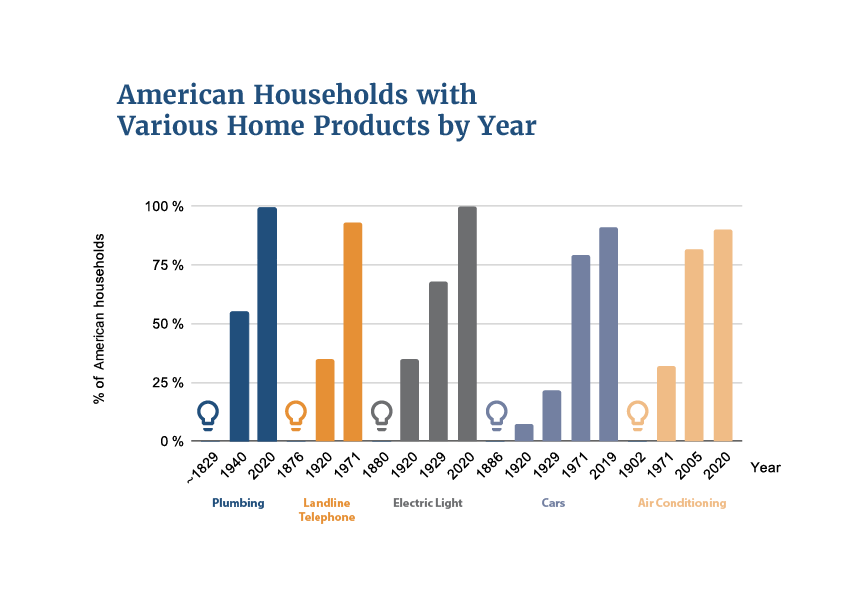

Only urban Americans had plumbing, though the principles of ventilation and sanitation were still in the process of being standardized. In 1920, Herbert Hoover, then Secretary of Commerce, started the Materials and Structures Division of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) and appointed Dr. Roy Hunter to the plumbing division. Dr. Hunter published studies through the 1930s and 40s that effectively created our modern standards of plumbing. Data from the 1940 census shows that 55 percent of households had indoor plumbing by that year, though it remained prone to frequent mishaps.

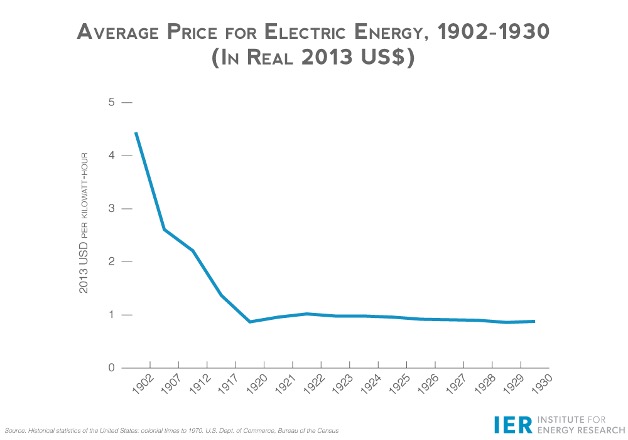

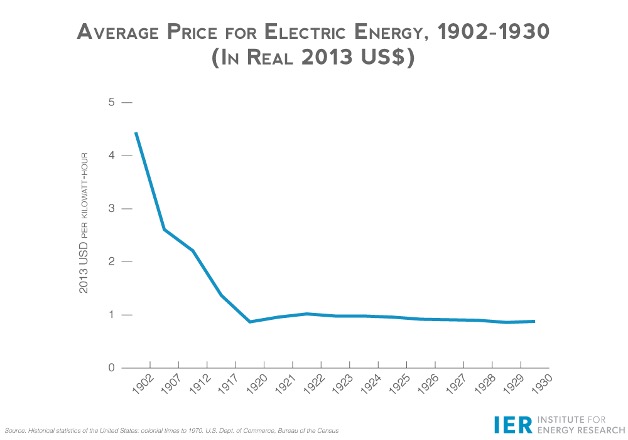

35 percent of households had electricity in 1920, but by 1929, this figure had grown to 68 percent. This growth was primarily due to the business savvy of Samuel Insull, who began his career as Thomas Edison’s personal assistant. Insull achieved economies of scale with electricity by consolidating mom-and-pop providers, diversifying his consumer base, and closing small generators in favor of larger, more efficient ones. He powered elevators and streetcars during the day and offered electricity from the same generators to provide consumers with lighting at night. The price of electricity dropped year after year as Insull expanded his reach, allowing electricity to mitigate many of the previous century’s difficulties.

Heating, plumbing, and electricity had all significantly improved over the last century as well. By 1920, Americans were no longer heating their homes with wood, but with coal, either through a coal-fired boiler in the basement that delivered steam to radiators in every room, or through riveted-steel coal furnaces that delivered heat by natural convection through ducts to the floors above.

Only urban Americans had plumbing, though the principles of ventilation and sanitation were still in the process of being standardized. In 1920, Herbert Hoover, then Secretary of Commerce, started the Materials and Structures Division of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) and appointed Dr. Roy Hunter to the plumbing division. Dr. Hunter published studies through the 1930s and 40s that effectively created our modern standards of plumbing. Data from the 1940 census shows that 55 percent of households had indoor plumbing by that year, though it remained prone to frequent mishaps.

35 percent of households had electricity in 1920, but by 1929, this figure had grown to 68 percent. This growth was primarily due to the business savvy of Samuel Insull, who began his career as Thomas Edison’s personal assistant. Insull achieved economies of scale with electricity by consolidating mom-and-pop providers, diversifying his consumer base, and closing small generators in favor of larger, more efficient ones. He powered elevators and streetcars during the day and offered electricity from the same generators to provide consumers with lighting at night. The price of electricity dropped year after year as Insull expanded his reach, allowing electricity to mitigate many of the previous century’s difficulties.

The American diet transformed to include a diverse and commercialized array of foods.

The advent of the automobile caused roadside diners to pop up along highways, offering cheap and fast American favorites such as hamburgers, French fries, milkshakes, and apple pies. The American diet became based on meat, potatoes, and heavy sweets like cakes and pies. Non-traditional food also became popular in some urban areas. The beginnings of world cuisines can be seen in the popular San Francisco Chop Suey restaurants of the period, which were affordable and trendy among young Americans. (The blend of meat, egg, and vegetables in this cuisine wasn’t truly Chinese, but Americans were predominately unaware of this.) Americans of the early twentieth century were also fascinated by Italian foods, like spaghetti and meatballs, which became a dinnertime favorite.

Refrigerators were not yet mass-produced in 1920 and cost around $1,000 a unit, but they would quickly become more popular. In 1927, General Electric produced the “Monitor-Top,” the first widely-consumed refrigerator, which sold over a million units. The 1900s also marked the advent of food processing—meaning that many foods were cheaper, more accessible, and already preserved. Familiar modern food brands like Coca Cola, Kellogg’s, Post, Wonder Bread, Hostess Cakes, Popsicles, Betty Crocker, and countless others already existed in 1920. In the midst of the prohibition era, speakeasies were of course prevalent, and the most popular drinks were gin rickeys (made of bathtub gin, lime juice, and seltzer), mint juleps, and champagne.

Transportation, communication, and the spread of information grew to new heights.

Railroads had been in operation for nearly a century, but the majority of tracks were laid in the half-century leading up to 1920. This amounted to five transcontinental railroads and over 200,000 miles of track, making travel to anywhere in the country more affordable and efficient. The invention of the steam locomotive, improved signal systems, and stronger and quieter cars (made of steel instead of wood) were major railroad innovations of the time. Pullman cars—private sleeping and dining cars with elaborate decoration such as plush seat cushions and chandeliers—were the pinnacle of railroad luxury. Many cities also had streetcars for transportation within city limits.

Vacations were another new trend, making cruises and ocean liners very popular. These ships began to incorporate all types of entertainment for the American family on vacation, including onboard swimming pools and movie theaters. The year 1920 also marked the dawn of the commercial airplane, with scheduled flights beginning in 1921. Flying from American coast to coast was not a pleasant experience on these first flights, and it was reserved for the very wealthy, as flights initially cost around $5000 per flight in modern dollars. These flights were longer than they are now, had barely any legroom, and the ride was bumpy and cold.

Communications technology had much improved over the last century as well. In 1920, the first commercial radio station in the United States (Pittsburgh’s KDKA) hit the airwaves. By the end of the 1920s, there were radios in 12 million households. People still sent telegrams across long distances, but 35 percent of American households also had telephones by 1920. Movies and movie theaters were also just emerging, bringing a new wave of entertainment and a large new industry to America.

The American diet transformed to include a diverse and commercialized array of foods.

The advent of the automobile caused roadside diners to pop up along highways, offering cheap and fast American favorites such as hamburgers, French fries, milkshakes, and apple pies. The American diet became based on meat, potatoes, and heavy sweets like cakes and pies. Non-traditional food also became popular in some urban areas. The beginnings of world cuisines can be seen in the popular San Francisco Chop Suey restaurants of the period, which were affordable and trendy among young Americans. (The blend of meat, egg, and vegetables in this cuisine wasn’t truly Chinese, but Americans were predominately unaware of this.) Americans of the early twentieth century were also fascinated by Italian foods, like spaghetti and meatballs, which became a dinnertime favorite.

Refrigerators were not yet mass-produced in 1920 and cost around $1,000 a unit, but they would quickly become more popular. In 1927, General Electric produced the “Monitor-Top,” the first widely-consumed refrigerator, which sold over a million units. The 1900s also marked the advent of food processing—meaning that many foods were cheaper, more accessible, and already preserved. Familiar modern food brands like Coca Cola, Kellogg’s, Post, Wonder Bread, Hostess Cakes, Popsicles, Betty Crocker, and countless others already existed in 1920. In the midst of the prohibition era, speakeasies were of course prevalent, and the most popular drinks were gin rickeys (made of bathtub gin, lime juice, and seltzer), mint juleps, and champagne.

Transportation, communication, and the spread of information grew to new heights.

Railroads had been in operation for nearly a century, but the majority of tracks were laid in the half-century leading up to 1920. This amounted to five transcontinental railroads and over 200,000 miles of track, making travel to anywhere in the country more affordable and efficient. The invention of the steam locomotive, improved signal systems, and stronger and quieter cars (made of steel instead of wood) were major railroad innovations of the time. Pullman cars—private sleeping and dining cars with elaborate decoration such as plush seat cushions and chandeliers—were the pinnacle of railroad luxury. Many cities also had streetcars for transportation within city limits.

Vacations were another new trend, making cruises and ocean liners very popular. These ships began to incorporate all types of entertainment for the American family on vacation, including onboard swimming pools and movie theaters. The year 1920 also marked the dawn of the commercial airplane, with scheduled flights beginning in 1921. Flying from American coast to coast was not a pleasant experience on these first flights, and it was reserved for the very wealthy, as flights initially cost around $5000 per flight in modern dollars. These flights were longer than they are now, had barely any legroom, and the ride was bumpy and cold.

Communications technology had much improved over the last century as well. In 1920, the first commercial radio station in the United States (Pittsburgh’s KDKA) hit the airwaves. By the end of the 1920s, there were radios in 12 million households. People still sent telegrams across long distances, but 35 percent of American households also had telephones by 1920. Movies and movie theaters were also just emerging, bringing a new wave of entertainment and a large new industry to America.

While only the richest 35 percent of Americans had electricity in 1920, 100 percent of American households have electricity today (compared to 89.6 percent of the world population). In contrast to the less than half of Americans who had indoor plumbing by 1920, 99.5 percent of American households have indoor plumbing today. Our homes are heated much more efficiently, with 60 percent of homes using gas-fired Forced Air Furnaces (FAUs) and 9 percent using oil-fired FAUs. For those in warmer climates, 25 percent of American homes use electric “heat pumps” for both heating and cooling needs. It wasn’t until the 1950s that household air conditioners came into use, but today almost 90 percent of American homes have air conditioning.

We travel in better conditions for cheaper and for shorter lengths of time. The internet gives us instant access to virtually unlimited information. We have developed vaccines for many deadly diseases like smallpox, polio, measles, influenza, etc. White bread, coveted in colonial America, is now available for less than a dollar a loaf, and we have fresh fruits and vegetables of a wide variety available in supermarkets all year round. Though some Americans still have more difficult lives than others, the innovations of the past have created a better life for all of us today and will continue to do so into the future. The American Dream is alive and well.

While only the richest 35 percent of Americans had electricity in 1920, 100 percent of American households have electricity today (compared to 89.6 percent of the world population). In contrast to the less than half of Americans who had indoor plumbing by 1920, 99.5 percent of American households have indoor plumbing today. Our homes are heated much more efficiently, with 60 percent of homes using gas-fired Forced Air Furnaces (FAUs) and 9 percent using oil-fired FAUs. For those in warmer climates, 25 percent of American homes use electric “heat pumps” for both heating and cooling needs. It wasn’t until the 1950s that household air conditioners came into use, but today almost 90 percent of American homes have air conditioning.

We travel in better conditions for cheaper and for shorter lengths of time. The internet gives us instant access to virtually unlimited information. We have developed vaccines for many deadly diseases like smallpox, polio, measles, influenza, etc. White bread, coveted in colonial America, is now available for less than a dollar a loaf, and we have fresh fruits and vegetables of a wide variety available in supermarkets all year round. Though some Americans still have more difficult lives than others, the innovations of the past have created a better life for all of us today and will continue to do so into the future. The American Dream is alive and well.

1720.

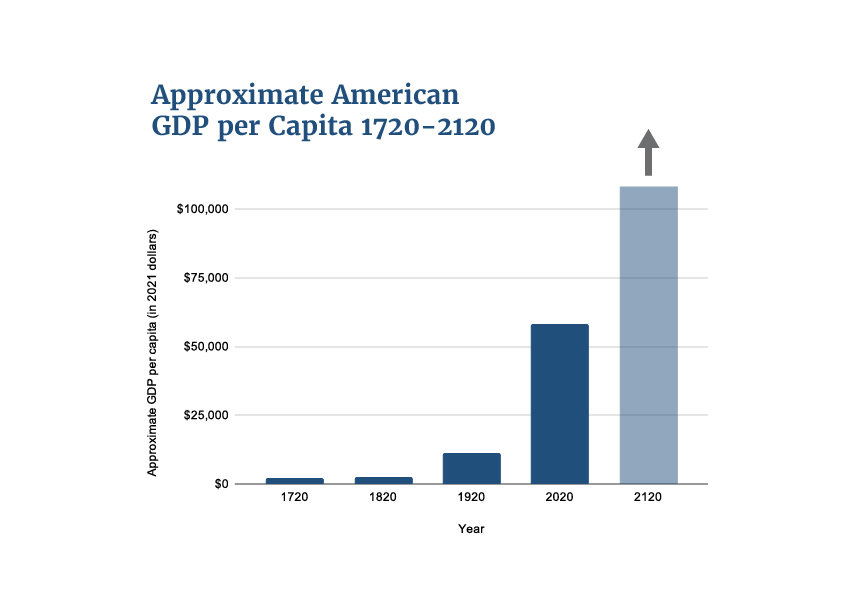

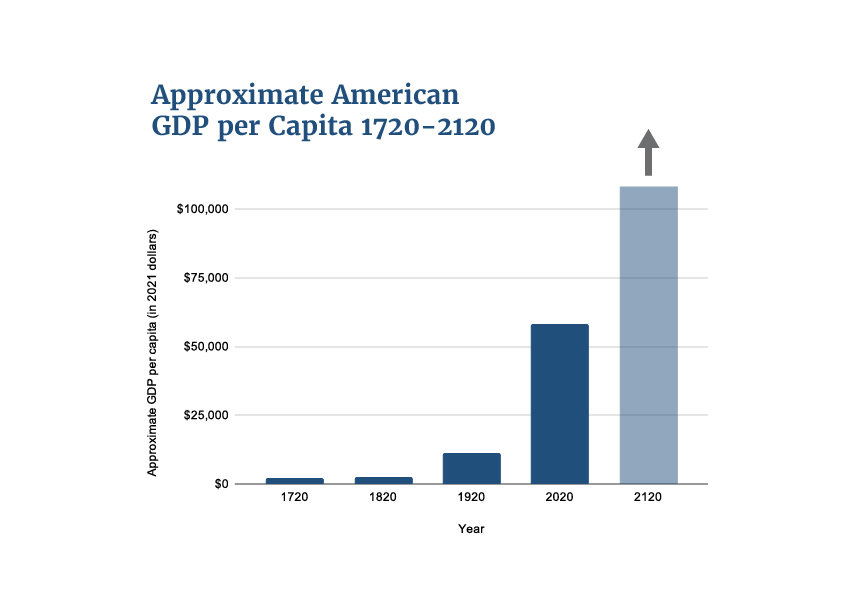

Over one hundred years after the 1607 founding of Jamestown, Europeans continued to travel to America’s shores seeking a new life of opportunity and prosperity. This was a well-founded choice since, by 1700, Americans had already overtaken British income per capita, and had around 50 percent more purchasing power than their British counterparts. These European travelers were the original American Dreamers, escaping the feudalistic economies and state-run churches of Europe. However, their life in the new world was by no means easy. Relative to today’s standards, all but the top few colonists lived in poverty. About 75 percent of the population belonged to the working middle class of craftsmen, teachers, and domestics who made goods like food, cloth, and candles from home. The best methodologies suggest that the average colonial American lived on much less than the average American does today. For example, we know that Jon Boucher, an upper-middle class schoolmaster in Virginia, earned an annual salary of £60 in 1759, approximately $4,000 a year in modern dollars. By contrast, the median annual salary for an elementary school teacher was about $60,000 in 2019 and America’s modern middle class, as defined by Pew Research Center, has a household income ranging from $48,500 to $145,500 a year. Outside of the middle class, a small portion of the colonial population were gentry, but the remainder were unskilled workers, indentured servants, and slaves. Slaves lived at bare-subsistence levels and died in great numbers. Indentured servants usually worked for four to seven years after arriving in America to pay off the cost of their voyage from England. (Imagine a one-way flight to Europe costing four to seven years’ salary!) Unskilled laborers had to travel frequently to find work and usually did not own property. Sacrifice was an unavoidable aspect of life in the New World, but early Americans’ pursuit of a better life founded the concept of the American Dream: making something for oneself from nothing, in a world brimming with opportunity. Independent of economic status, all colonists lived without running water, plumbing, and electricity. No mechanism for home cooling yet existed and heating the home was a much longer and more complicated process than simply turning up the thermostat. Families chopped their own wood for fuel, and if it ran out would have to brave the New England winter to chop some more. Luckily, at least for heating purposes, homes would likely only have one room, no matter how large the family, so the brick fireplace (on which families also cooked their food) could heat the entire home. The colonists didn’t own much furniture either: likely just a bench, a table, and some chests for storing clothing, with a straw mattress on the floor for a bed. Colonists typically built their own homes, usually a “wattle and daub” house with a thatched roof made of wood, sticks, clay, mud, and grass. Compared to today, the colonial diet was banal and unvarying. Bread was the most important staple of the colonial diet. The typical middle-class colonist ate coarse and unrefined rye or wheat bread (only the gentry could afford refined white bread). Unlike today, fresh fruits and vegetables couldn’t be imported long distances, making out-of-season fruits either impossible to acquire or extremely expensive. A typical colonial breakfast consisted of bread or cornmeal with milk or tea. Dinner, the largest meal of the day, occurred around noon and would normally consist of one meat or seafood dish and a couple of vegetable dishes (pumpkin, squash, and beans were staples). The evening’s supper would usually consist of bread, cheese, some type of mush, and leftovers from dinner. Middle-class delicacies for rare occasions included beaver and beaver tail (especially as the fur trade picked up), and ambergris, or whale vomit, which was in great supply due to the New England whaling industry. Turtle was an extreme delicacy and turtle roasts were high-society events, only enjoyed by the most well-off on special occasions. Transportation and communication were tremendously difficult in colonial times. Colonial American roads resembled haphazardly cleared backcountry trails. The most common form of travel was by horse or horse-drawn wagon, with the exception of the gentry, who would likely have a horse-drawn carriage instead. If one wished to communicate privately, a horseback messenger would be necessary. Public communication was conducted with broadsides—large sheets of printed paper posted on trees or buildings in town. Newspapers didn’t become popular until they publicized the case for American independence later in the century. Colonial New England boasted the highest rate of book ownership in the world, but most books needed to be imported from London, meaning that they were much more expensive than in later centuries. The high price of books meant that, while many people owned a few books, few owned many. The most popular titles in personal libraries at the time included the Bible, Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, Harris’ New England Primer, Locke’s Treatise of Civil Government, and Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. While personal libraries were limited, Americans’ passion for books inspired Benjamin Franklin to open the first public library in Philadelphia in 1731.1820.

A century later, America’s GDP per capita was up to about $2,500 in modern dollars. There were now 22 states in the Union, with Maine joining in 1820, followed by Missouri in 1821. Americans had new constitutional protections under the Bill of Rights, including freedom of speech, the protection of property, and a right to due process. Though American life had progressed by leaps and bounds over the last century (especially due to the burgeoning Industrial Revolution), certain aspects of American life remained horrendous by today’s standards. Racial minorities suffered greatly, urban life was miserable for the poor, and transatlantic immigratory conditions were horrific.

The Atlantic slave trade was abolished in 1808, but American slavery was entering its most conspicious period in national history, with 16 percent of our total population and 85 percent of all blacks living in slavery in 1820. Native Americans were not yet considered American citizens and were likely to be living in virtual slavery or in a tribe which the federal government would soon move west of the Mississippi River.

European immigration turned from a trickle into a gush that lasted through the 1860s. Most of these immigrants crossed the Atlantic below-deck on packet ships, which carried people, mail, and other cargo. Steerage was a dark, crowded, and damp experience for these passengers. Conditions were unsanitary and the sea was rough, meaning that it was messy and foul-smelling below deck, and that rats, insects, and disease were common. The Steerage Act of 1819 somewhat improved the horrible conditions for immigrants onboard transatlantic ships, but nonetheless, many immigrants arrived sick or dying in the major port cities of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston. These immigrants (mostly Irish and German), however, were willing to suffer through such conditions in order to pursue the economic opportunity and religious and political freedoms that America promised.

Since municipalities were responsible for providing for the poor in their city, local governments discouraged poverty by punishing it. To enter a poorhouse, most states required a public confession swearing to a lack of worldly goods and a need for assistance. Temporarily unemployed, able-bodied men would come and go from these horrific, bare-bones facilities, but the permanent “inmates” usually included the city’s destitute alcoholic, aging, and mentally- or physically-disabled populations. One of the most notorious poorhouses was Tewksbury Almshouse in Massachusetts, where abuse from overseers was rampant, inmates all used the same bathwater though many had open sores, patients in the insane ward were left for days without food, and vermin ate holes in the heads of the sick.

The influx of immigrants into port cities meant that poorhouses were overcrowded and filthy: the poorhouse population in New York City tripled from 1800 to 1820, and more than a seventh of the city’s residents received public or private relief. The boom of unskilled laborers drove down wages for the working class and made finding work extremely difficult for the poor.

For non-city dwellers, the American diet remained dull. But the diet of America’s urban population began to diversify as dining out became an accessible experience.

While transportation was faster after the Industrial Revolution, it was still very slow by today’s standards. This meant that for New Englanders, it would be a rare treat to eat a grapefruit or an orange from Florida. Vegetables had to be eaten pickled during the winter months, and in rural areas, people continued to eat what was available locally, either from their own farms, or could be purchased in town. Spices other than salt remained a luxury, and preparing meals was still a lot of hard work—the ordinary mid- to lower-class American family still hunted, farmed, and preserved the majority of their own food.

Before the turn of the century, food was only served at inns and hotels. But while cities expanded along the seaboard, the distance between work and residence increased. More hungry customers stopped in at popular new oyster bars and taverns. Big-city hotels also began to open up, most notably Baltimore’s City Hotel (1826), Philadelphia’s United States Hotel (1827), Washington’s National Hotel (1827), and Boston’s Tremont Hotel (1829). These popular hotels had large dining rooms that served soup, meat, vegetables, and puddings. Menus were usually not printed, but recited by waiters. The influx of immigrants in cities also meant more diverse fare was offered, with French restaurants and European-style confectioner’s shops among the most popular new offerings.

Though many aspects of life remained hard, increased industrialization and economic development meant that the average American had access to new technologies and lower prices than before.

Electricity, plumbing, and heating as we now know them remained non-existent in 1820, and home heating was still either done with a brick fireplace, or with the cast-iron Franklin Stove, first invented in 1742. But in 1829, Boston’s Tremont Hotel became the first known American building with indoor plumbing, using water drawn from a rooftop metal storage tank that was fed by the newly-invented steam pump. This plumbing, however, was rudimentary at best, and modern plumbing would still take over a century to perfect.

Kicking off the American Industrial Revolution, in 1790 Samuel Slater introduced the first industrial cotton mill to the United States. By 1820, factories began to appear throughout New England, making it possible to perform work on a large scale in centralized locations, thereby increasing productivity and lowering the prices of many goods. A large majority of the new New England factory workers were young girls recruited from surrounding farms. These girls could be paid less than male workers, and in turn, they enjoyed a newfound independence from rural male-dominated households.

Construction began on New York’s Erie Canal in 1817, connecting the Eastern seaboard to the Old Northwest. This highly successful canal project set off a canal frenzy in the US: By 1840, over 3,000 miles of canal had been built, including a complete waterway from New York to New Orleans. Paired with the novel steamboat (first built by American inventor Robert Fulton in 1807), travel became faster and cheaper. Land travel had much improved over the last century as well: States began to charter privately-run turnpikes, which charged fees for use. New York was the leader in this arena, increasing its state roads from 1,000 miles in 1810 to 4,000 miles by 1820. Improvements in transportation, along with the new printing technologies of the century and the implementation of the United States Postal Service in 1775, made the mass-produced newspaper possible.

Racial minorities suffered greatly, urban life was miserable for the poor, and transatlantic immigratory conditions were horrific.

The Atlantic slave trade was abolished in 1808, but American slavery was entering its most conspicious period in national history, with 16 percent of our total population and 85 percent of all blacks living in slavery in 1820. Native Americans were not yet considered American citizens and were likely to be living in virtual slavery or in a tribe which the federal government would soon move west of the Mississippi River.

European immigration turned from a trickle into a gush that lasted through the 1860s. Most of these immigrants crossed the Atlantic below-deck on packet ships, which carried people, mail, and other cargo. Steerage was a dark, crowded, and damp experience for these passengers. Conditions were unsanitary and the sea was rough, meaning that it was messy and foul-smelling below deck, and that rats, insects, and disease were common. The Steerage Act of 1819 somewhat improved the horrible conditions for immigrants onboard transatlantic ships, but nonetheless, many immigrants arrived sick or dying in the major port cities of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston. These immigrants (mostly Irish and German), however, were willing to suffer through such conditions in order to pursue the economic opportunity and religious and political freedoms that America promised.

Since municipalities were responsible for providing for the poor in their city, local governments discouraged poverty by punishing it. To enter a poorhouse, most states required a public confession swearing to a lack of worldly goods and a need for assistance. Temporarily unemployed, able-bodied men would come and go from these horrific, bare-bones facilities, but the permanent “inmates” usually included the city’s destitute alcoholic, aging, and mentally- or physically-disabled populations. One of the most notorious poorhouses was Tewksbury Almshouse in Massachusetts, where abuse from overseers was rampant, inmates all used the same bathwater though many had open sores, patients in the insane ward were left for days without food, and vermin ate holes in the heads of the sick.

The influx of immigrants into port cities meant that poorhouses were overcrowded and filthy: the poorhouse population in New York City tripled from 1800 to 1820, and more than a seventh of the city’s residents received public or private relief. The boom of unskilled laborers drove down wages for the working class and made finding work extremely difficult for the poor.

For non-city dwellers, the American diet remained dull. But the diet of America’s urban population began to diversify as dining out became an accessible experience.

While transportation was faster after the Industrial Revolution, it was still very slow by today’s standards. This meant that for New Englanders, it would be a rare treat to eat a grapefruit or an orange from Florida. Vegetables had to be eaten pickled during the winter months, and in rural areas, people continued to eat what was available locally, either from their own farms, or could be purchased in town. Spices other than salt remained a luxury, and preparing meals was still a lot of hard work—the ordinary mid- to lower-class American family still hunted, farmed, and preserved the majority of their own food.

Before the turn of the century, food was only served at inns and hotels. But while cities expanded along the seaboard, the distance between work and residence increased. More hungry customers stopped in at popular new oyster bars and taverns. Big-city hotels also began to open up, most notably Baltimore’s City Hotel (1826), Philadelphia’s United States Hotel (1827), Washington’s National Hotel (1827), and Boston’s Tremont Hotel (1829). These popular hotels had large dining rooms that served soup, meat, vegetables, and puddings. Menus were usually not printed, but recited by waiters. The influx of immigrants in cities also meant more diverse fare was offered, with French restaurants and European-style confectioner’s shops among the most popular new offerings.

Though many aspects of life remained hard, increased industrialization and economic development meant that the average American had access to new technologies and lower prices than before.

Electricity, plumbing, and heating as we now know them remained non-existent in 1820, and home heating was still either done with a brick fireplace, or with the cast-iron Franklin Stove, first invented in 1742. But in 1829, Boston’s Tremont Hotel became the first known American building with indoor plumbing, using water drawn from a rooftop metal storage tank that was fed by the newly-invented steam pump. This plumbing, however, was rudimentary at best, and modern plumbing would still take over a century to perfect.

Kicking off the American Industrial Revolution, in 1790 Samuel Slater introduced the first industrial cotton mill to the United States. By 1820, factories began to appear throughout New England, making it possible to perform work on a large scale in centralized locations, thereby increasing productivity and lowering the prices of many goods. A large majority of the new New England factory workers were young girls recruited from surrounding farms. These girls could be paid less than male workers, and in turn, they enjoyed a newfound independence from rural male-dominated households.

Construction began on New York’s Erie Canal in 1817, connecting the Eastern seaboard to the Old Northwest. This highly successful canal project set off a canal frenzy in the US: By 1840, over 3,000 miles of canal had been built, including a complete waterway from New York to New Orleans. Paired with the novel steamboat (first built by American inventor Robert Fulton in 1807), travel became faster and cheaper. Land travel had much improved over the last century as well: States began to charter privately-run turnpikes, which charged fees for use. New York was the leader in this arena, increasing its state roads from 1,000 miles in 1810 to 4,000 miles by 1820. Improvements in transportation, along with the new printing technologies of the century and the implementation of the United States Postal Service in 1775, made the mass-produced newspaper possible.

1920.

By the Roaring Twenties, 48 states (all but Alaska and Hawaii) had joined the Union and America’s GDP per capita had increased nearly fivefold, reaching approximately $11,000 in current dollars in 1920. In this year, women received the right to vote, the Prohibition era began, and the modern-day Olympic flag debuted. It was easier than ever to start a business due to more permissive state incorporation laws and increased domestic laissez-faire economic policy. Despite continued hardships for racial minorities and immigrants, economic growth over the past century meant that life continued to improve for all Americans, even the least well-off. As in preceding centuries, immigrants and racial minorities had a particularly hard life. On average, 25,000 Mexicans immigrated to the United States per year at this time, most of whom ended up living in extreme poverty. Most Mexican-American homes didn’t have toilets or running water, and one survey found that 40 percent of Mexican-American households couldn’t afford milk, meat, or fresh fruits or vegetables for their children. Similarly, while African Americans were no longer enslaved, if they lived in the South they faced a particularly difficult life. At the height of the segregation era, the majority of southern blacks were impoverished sharecroppers. Native Americans weren’t faring well either: They didn’t receive citizenship until 1924, and a 1928 report found that 50 percent of the indigenous population owned less than $500, while 70 percent lived on less than $200 a year. But for the average American family, and even for racial minorities, aggressive economic growth after World War I meant that previous luxuries were now more affordable. In the twentieth century, for example, the typical middle-class family could afford a car. In 1920, 7.5 percent of Americans owned a personal vehicle and this number was about to skyrocket, almost tripling by the end of the decade. Henry Ford also implemented the 40-hour work week, improving the quality of life for low-income factory workers, who now had weekends off and could join in on the consumerism of the upper and middle classes. Heating, plumbing, and electricity had all significantly improved over the last century as well. By 1920, Americans were no longer heating their homes with wood, but with coal, either through a coal-fired boiler in the basement that delivered steam to radiators in every room, or through riveted-steel coal furnaces that delivered heat by natural convection through ducts to the floors above.

Only urban Americans had plumbing, though the principles of ventilation and sanitation were still in the process of being standardized. In 1920, Herbert Hoover, then Secretary of Commerce, started the Materials and Structures Division of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) and appointed Dr. Roy Hunter to the plumbing division. Dr. Hunter published studies through the 1930s and 40s that effectively created our modern standards of plumbing. Data from the 1940 census shows that 55 percent of households had indoor plumbing by that year, though it remained prone to frequent mishaps.

35 percent of households had electricity in 1920, but by 1929, this figure had grown to 68 percent. This growth was primarily due to the business savvy of Samuel Insull, who began his career as Thomas Edison’s personal assistant. Insull achieved economies of scale with electricity by consolidating mom-and-pop providers, diversifying his consumer base, and closing small generators in favor of larger, more efficient ones. He powered elevators and streetcars during the day and offered electricity from the same generators to provide consumers with lighting at night. The price of electricity dropped year after year as Insull expanded his reach, allowing electricity to mitigate many of the previous century’s difficulties.

Heating, plumbing, and electricity had all significantly improved over the last century as well. By 1920, Americans were no longer heating their homes with wood, but with coal, either through a coal-fired boiler in the basement that delivered steam to radiators in every room, or through riveted-steel coal furnaces that delivered heat by natural convection through ducts to the floors above.

Only urban Americans had plumbing, though the principles of ventilation and sanitation were still in the process of being standardized. In 1920, Herbert Hoover, then Secretary of Commerce, started the Materials and Structures Division of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) and appointed Dr. Roy Hunter to the plumbing division. Dr. Hunter published studies through the 1930s and 40s that effectively created our modern standards of plumbing. Data from the 1940 census shows that 55 percent of households had indoor plumbing by that year, though it remained prone to frequent mishaps.

35 percent of households had electricity in 1920, but by 1929, this figure had grown to 68 percent. This growth was primarily due to the business savvy of Samuel Insull, who began his career as Thomas Edison’s personal assistant. Insull achieved economies of scale with electricity by consolidating mom-and-pop providers, diversifying his consumer base, and closing small generators in favor of larger, more efficient ones. He powered elevators and streetcars during the day and offered electricity from the same generators to provide consumers with lighting at night. The price of electricity dropped year after year as Insull expanded his reach, allowing electricity to mitigate many of the previous century’s difficulties.

The American diet transformed to include a diverse and commercialized array of foods.

The advent of the automobile caused roadside diners to pop up along highways, offering cheap and fast American favorites such as hamburgers, French fries, milkshakes, and apple pies. The American diet became based on meat, potatoes, and heavy sweets like cakes and pies. Non-traditional food also became popular in some urban areas. The beginnings of world cuisines can be seen in the popular San Francisco Chop Suey restaurants of the period, which were affordable and trendy among young Americans. (The blend of meat, egg, and vegetables in this cuisine wasn’t truly Chinese, but Americans were predominately unaware of this.) Americans of the early twentieth century were also fascinated by Italian foods, like spaghetti and meatballs, which became a dinnertime favorite.

Refrigerators were not yet mass-produced in 1920 and cost around $1,000 a unit, but they would quickly become more popular. In 1927, General Electric produced the “Monitor-Top,” the first widely-consumed refrigerator, which sold over a million units. The 1900s also marked the advent of food processing—meaning that many foods were cheaper, more accessible, and already preserved. Familiar modern food brands like Coca Cola, Kellogg’s, Post, Wonder Bread, Hostess Cakes, Popsicles, Betty Crocker, and countless others already existed in 1920. In the midst of the prohibition era, speakeasies were of course prevalent, and the most popular drinks were gin rickeys (made of bathtub gin, lime juice, and seltzer), mint juleps, and champagne.

Transportation, communication, and the spread of information grew to new heights.

Railroads had been in operation for nearly a century, but the majority of tracks were laid in the half-century leading up to 1920. This amounted to five transcontinental railroads and over 200,000 miles of track, making travel to anywhere in the country more affordable and efficient. The invention of the steam locomotive, improved signal systems, and stronger and quieter cars (made of steel instead of wood) were major railroad innovations of the time. Pullman cars—private sleeping and dining cars with elaborate decoration such as plush seat cushions and chandeliers—were the pinnacle of railroad luxury. Many cities also had streetcars for transportation within city limits.

Vacations were another new trend, making cruises and ocean liners very popular. These ships began to incorporate all types of entertainment for the American family on vacation, including onboard swimming pools and movie theaters. The year 1920 also marked the dawn of the commercial airplane, with scheduled flights beginning in 1921. Flying from American coast to coast was not a pleasant experience on these first flights, and it was reserved for the very wealthy, as flights initially cost around $5000 per flight in modern dollars. These flights were longer than they are now, had barely any legroom, and the ride was bumpy and cold.

Communications technology had much improved over the last century as well. In 1920, the first commercial radio station in the United States (Pittsburgh’s KDKA) hit the airwaves. By the end of the 1920s, there were radios in 12 million households. People still sent telegrams across long distances, but 35 percent of American households also had telephones by 1920. Movies and movie theaters were also just emerging, bringing a new wave of entertainment and a large new industry to America.

The American diet transformed to include a diverse and commercialized array of foods.

The advent of the automobile caused roadside diners to pop up along highways, offering cheap and fast American favorites such as hamburgers, French fries, milkshakes, and apple pies. The American diet became based on meat, potatoes, and heavy sweets like cakes and pies. Non-traditional food also became popular in some urban areas. The beginnings of world cuisines can be seen in the popular San Francisco Chop Suey restaurants of the period, which were affordable and trendy among young Americans. (The blend of meat, egg, and vegetables in this cuisine wasn’t truly Chinese, but Americans were predominately unaware of this.) Americans of the early twentieth century were also fascinated by Italian foods, like spaghetti and meatballs, which became a dinnertime favorite.

Refrigerators were not yet mass-produced in 1920 and cost around $1,000 a unit, but they would quickly become more popular. In 1927, General Electric produced the “Monitor-Top,” the first widely-consumed refrigerator, which sold over a million units. The 1900s also marked the advent of food processing—meaning that many foods were cheaper, more accessible, and already preserved. Familiar modern food brands like Coca Cola, Kellogg’s, Post, Wonder Bread, Hostess Cakes, Popsicles, Betty Crocker, and countless others already existed in 1920. In the midst of the prohibition era, speakeasies were of course prevalent, and the most popular drinks were gin rickeys (made of bathtub gin, lime juice, and seltzer), mint juleps, and champagne.

Transportation, communication, and the spread of information grew to new heights.

Railroads had been in operation for nearly a century, but the majority of tracks were laid in the half-century leading up to 1920. This amounted to five transcontinental railroads and over 200,000 miles of track, making travel to anywhere in the country more affordable and efficient. The invention of the steam locomotive, improved signal systems, and stronger and quieter cars (made of steel instead of wood) were major railroad innovations of the time. Pullman cars—private sleeping and dining cars with elaborate decoration such as plush seat cushions and chandeliers—were the pinnacle of railroad luxury. Many cities also had streetcars for transportation within city limits.

Vacations were another new trend, making cruises and ocean liners very popular. These ships began to incorporate all types of entertainment for the American family on vacation, including onboard swimming pools and movie theaters. The year 1920 also marked the dawn of the commercial airplane, with scheduled flights beginning in 1921. Flying from American coast to coast was not a pleasant experience on these first flights, and it was reserved for the very wealthy, as flights initially cost around $5000 per flight in modern dollars. These flights were longer than they are now, had barely any legroom, and the ride was bumpy and cold.

Communications technology had much improved over the last century as well. In 1920, the first commercial radio station in the United States (Pittsburgh’s KDKA) hit the airwaves. By the end of the 1920s, there were radios in 12 million households. People still sent telegrams across long distances, but 35 percent of American households also had telephones by 1920. Movies and movie theaters were also just emerging, bringing a new wave of entertainment and a large new industry to America.

2020.

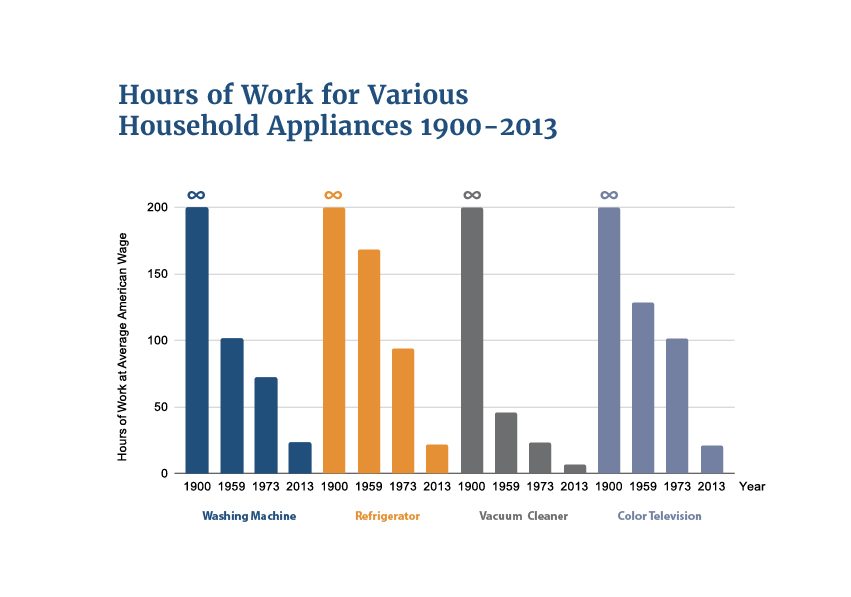

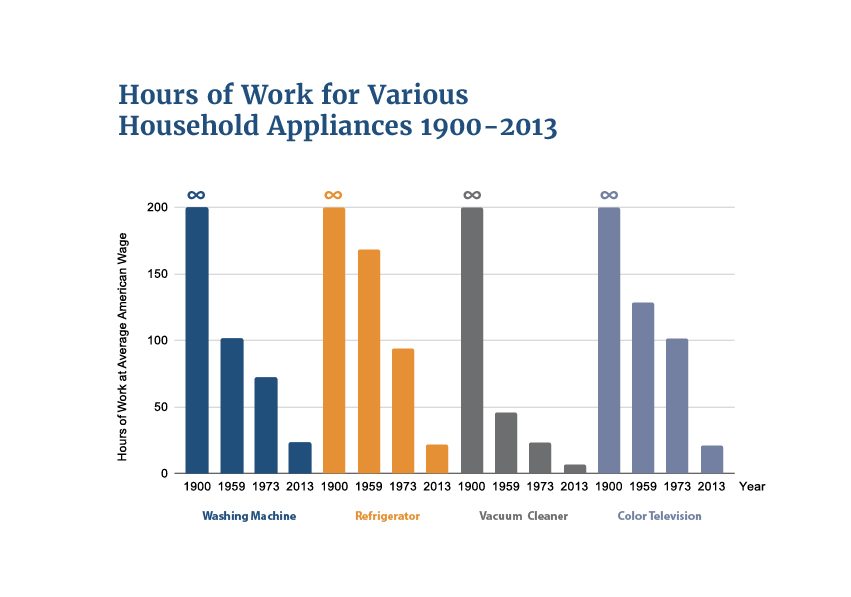

America’s GDP per capita rose to about $63,000 in 2020. This figure is quickly approaching English economist John Meynard Keynes’ prediction from his 1930 essay “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren,” in which he approximated that “the capital equipment of the world will have increased … seven and a half times in a hundred years.” In 2020, Joe Biden won a highly contentious presidential race, there were widespread racial protests as part of the Black Lives Matter movement, and the devastating coronavirus pandemic broke out, impacting the daily life of every American. Despite all of these setbacks, the economic outlook for our country remains strong. Americans live more comfortably and with more advanced technology at lower prices than ever before while civil rights movements over the last century have increased economic and social freedoms for Americans of all walks of life. Economic development spurred by market competition has continued to drive down costs of production for material goods that were previously luxuries. Increased purchasing power means that more of America’s poor own products that we couldn’t have even imagined a century ago. For example, while 100 percent of people with an annual income above $75,000 own a cell phone today, a shocking 95 percent of people with an annual income below $30,000 also own one. (Remember, in 1920 only 35 percent of American households owned a landline telephone.) To take another example, a color TV required 128 hours of work at the average wage in 1959. It required 101 hours of work at the 1973 average wage. At the 2013 average wage, it only costs 21 hours of work. This pattern of increased purchasing power holds true across a wide variety of goods: food, household appliances, clothing, technology, and more. While only the richest 35 percent of Americans had electricity in 1920, 100 percent of American households have electricity today (compared to 89.6 percent of the world population). In contrast to the less than half of Americans who had indoor plumbing by 1920, 99.5 percent of American households have indoor plumbing today. Our homes are heated much more efficiently, with 60 percent of homes using gas-fired Forced Air Furnaces (FAUs) and 9 percent using oil-fired FAUs. For those in warmer climates, 25 percent of American homes use electric “heat pumps” for both heating and cooling needs. It wasn’t until the 1950s that household air conditioners came into use, but today almost 90 percent of American homes have air conditioning.

We travel in better conditions for cheaper and for shorter lengths of time. The internet gives us instant access to virtually unlimited information. We have developed vaccines for many deadly diseases like smallpox, polio, measles, influenza, etc. White bread, coveted in colonial America, is now available for less than a dollar a loaf, and we have fresh fruits and vegetables of a wide variety available in supermarkets all year round. Though some Americans still have more difficult lives than others, the innovations of the past have created a better life for all of us today and will continue to do so into the future. The American Dream is alive and well.

While only the richest 35 percent of Americans had electricity in 1920, 100 percent of American households have electricity today (compared to 89.6 percent of the world population). In contrast to the less than half of Americans who had indoor plumbing by 1920, 99.5 percent of American households have indoor plumbing today. Our homes are heated much more efficiently, with 60 percent of homes using gas-fired Forced Air Furnaces (FAUs) and 9 percent using oil-fired FAUs. For those in warmer climates, 25 percent of American homes use electric “heat pumps” for both heating and cooling needs. It wasn’t until the 1950s that household air conditioners came into use, but today almost 90 percent of American homes have air conditioning.

We travel in better conditions for cheaper and for shorter lengths of time. The internet gives us instant access to virtually unlimited information. We have developed vaccines for many deadly diseases like smallpox, polio, measles, influenza, etc. White bread, coveted in colonial America, is now available for less than a dollar a loaf, and we have fresh fruits and vegetables of a wide variety available in supermarkets all year round. Though some Americans still have more difficult lives than others, the innovations of the past have created a better life for all of us today and will continue to do so into the future. The American Dream is alive and well.

2120.

By 2120, the world population will have leveled off at around 11 billion people, growing at less than 0.1 percent per year (compared to the 1 to 2 percent growth that we currently experience each year). If America’s GDP per capita rises another 475 percent this century (though it will likely grow even more than that), it will approach $362,000 in today’s dollars. When it is normal to make millions of dollars a year, the least well-off Americans may not be able to afford property in space or the latest augmented reality technologies, but will nonetheless be extremely wealthy by today’s standards. America’s history indicates that a century from now, Americans will be prosperous beyond imagination. Innovation in healthcare will allow us to live longer, happier, and healthier lives. Imagine being able to have five or six generations together for your annual family reunion! Breakthroughs in biotechnology in the coming century will likely result in longer life expectancy and solutions to many of America’s deadliest health problems. Right now, scientists are designing tiny robots and genetically-modified bacteria that can enter your body, complete a health-related task, and exit, all on their own. We might also begin to bioprint new organs like livers and kidneys, putting an end to many of the most complicated and risky surgeries that exist today. In addition, we can imagine efficient computerized precision medicine that will monitor all of your symptoms on a daily basis and know when you are sick, how to remedy your illnesses, and how to prevent them in the future. In the same vein, we might have technology that can detect and understand mental states and mental health. Like a personal and readily-available psychologist, this technology could coach us to feel better about ourselves, have a more positive outlook on life, and be more productive due to a happy and healthy state of mind. Homes and their contents will be more comfortable, enjoyable, and beautiful than ever before. Right now, you have to wait about two days for your Amazon Prime order to arrive. Imagine that instead, you only had to wait two seconds. In 2120, at-home replicators that make realistic copies of any material object might exist and be in the process of becoming common in American households. As we speak, scientists are working on programmable matter, which is matter that can be turned into any other type of matter upon command. The best working model of this so far is in the form of a swarm of miniscule robots that can reconfigure themselves into a chair, a table, or a bed. But development of a “bucket of stuff” that can be flexible like a rubber band, but also firm like wood or metal is already in progress. Over the next century, we will see an evolution in at-home entertainment as well. Instead of playing Xbox on a TV screen, you might be able not just to hear and see a virtual world, but to smell, feel, and taste the objects in that world as well. In addition to virtual reality, augmented reality (that interacts with actual reality) is currently in development. This means you could put in a contact lens and be able to decorate your home in a realistic manner, on command. If you wanted a vase of flowers on your dining room table, all you would have to do is say so, and the augmented reality device will create a beautiful bouquet that looks just like the real thing. Decorating for the holiday season will be a breeze. Physical devices like screens, phones, smart watches, and other wearables will probably begin to disappear as tech starts to blend in seamlessly with the rest of our environment. For instance, brain implants with certain virtual or augmented reality features may become available. Or rooms might start to be outfitted with cheap ultra-high-definition light-emitting materials that can beam light directly into your eyes for perfect virtual or augmented reality experiences. A century from now it is also likely that most people will be able to afford their own large and beautiful homes, although many people will probably still choose to live in more social environments. The average American will be able to afford to design and build cool and creative new neighborhoods in collaboration with friends and family. Perhaps some will choose to live in spacious cities with buildings, transit, and walkways that go hundreds of stories underground, yet feel light and open. When design and building technologies become more affordable for all, this will unleash a yet-untapped creativity and personalization for our public and private spaces. New space technologies will mean much-improved travel experiences and far-off new colonies. Complaining about commercial airline travel is practically an American tradition by now, but new developments in space technology promise to resolve any and all travel discomfort in the coming years. By 2120, the average American should be able to get anywhere in the world affordably in 45 minutes or less with a personal pod that smoothly enters and exits orbit around the earth at high speeds. This means no more screaming babies, no more kids kicking your seat, and no more 15-hour flights with no legroom. Besides travel, developments in space technology also promise space colonies in the relatively near future. Right now, it costs about $10,000 to send one pound of material to space. That’s a cost of about $1.9 million for the average American man and $1.7 million for the average American woman to enter space at today’s prices. But some of our best and brightest minds are hard at work on making space travel affordable to the average person, meaning that within the next century, we may have already started on space colony construction. One of the biggest resources in this area is asteroid mining technology, which means that we can build colonies with materials that are already in space, rather than spending lots of money and energy trying to blast them off into space from Earth. Last, our largest societal and environmental problems will likely be resolved. Nuclear fusion technology has the potential to remedy all of our concerns about climate change by effortlessly absorbing unlimited amounts of carbon. It also promises to make energy so cheap that we can power realistic-looking lights in beautiful and airy underground cities while enormously reducing the cost of electricity. But even without large-scale technological breakthroughs, increased societal wealth alone may mitigate climate change through carbon capture and other currently costly techniques. With another century of economic and technological development, it will be so cheap to provide the basic necessities of life that every American will have access to healthy food, safe shelter, sanitary conditions, and precise healthcare services. Because these will be taken care of at a much cheaper rate than today, we can imagine that the information, media, and entertainment industries will take up much greater parts of the economy. Even the least well-off Americans will have extra money to spend on virtual and augmented reality headsets and the latest in information technology. Because of American devotion to the continued betterment of all aspects of life, our country’s future is one of great opportunity and prosperity for all. We are becoming consistently freer from the life-threatening fundamental problems of the past, and continually more able to work on loftier goals. The American Dream has evolved to include women, minorities, and others who were once excluded, and it will continue to evolve into a more inclusive and prosperous ethos in the future. So long as we continue to preserve our economic growth and to allow the free competition of ideas to drive progress, America’s best days are ahead of her.

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about our fight for policies at the state level that restore liberty, accountability, and innovation in American governance.