Waikiki: A Public-Private Solution to Reducing Unsheltered Homelessness

Homelessness in the United States is at an all-time high, with 2024 revealing an unprecedented 771,470 people experiencing homelessness on a single night (an 18% increase when compared to 2023). While the nation has engaged in a 16-year failed experiment to reduce homelessness, states, cities, and communities are realizing that there are practical solutions that can be employed today with immediate benefits. This problem requires a multi-pronged approach (i.e., the right incentives, deterrents, high-touch community engagement, clinical support, housing and shelter), and one business community in Hawaii is leading by example.

Identifying the Problem

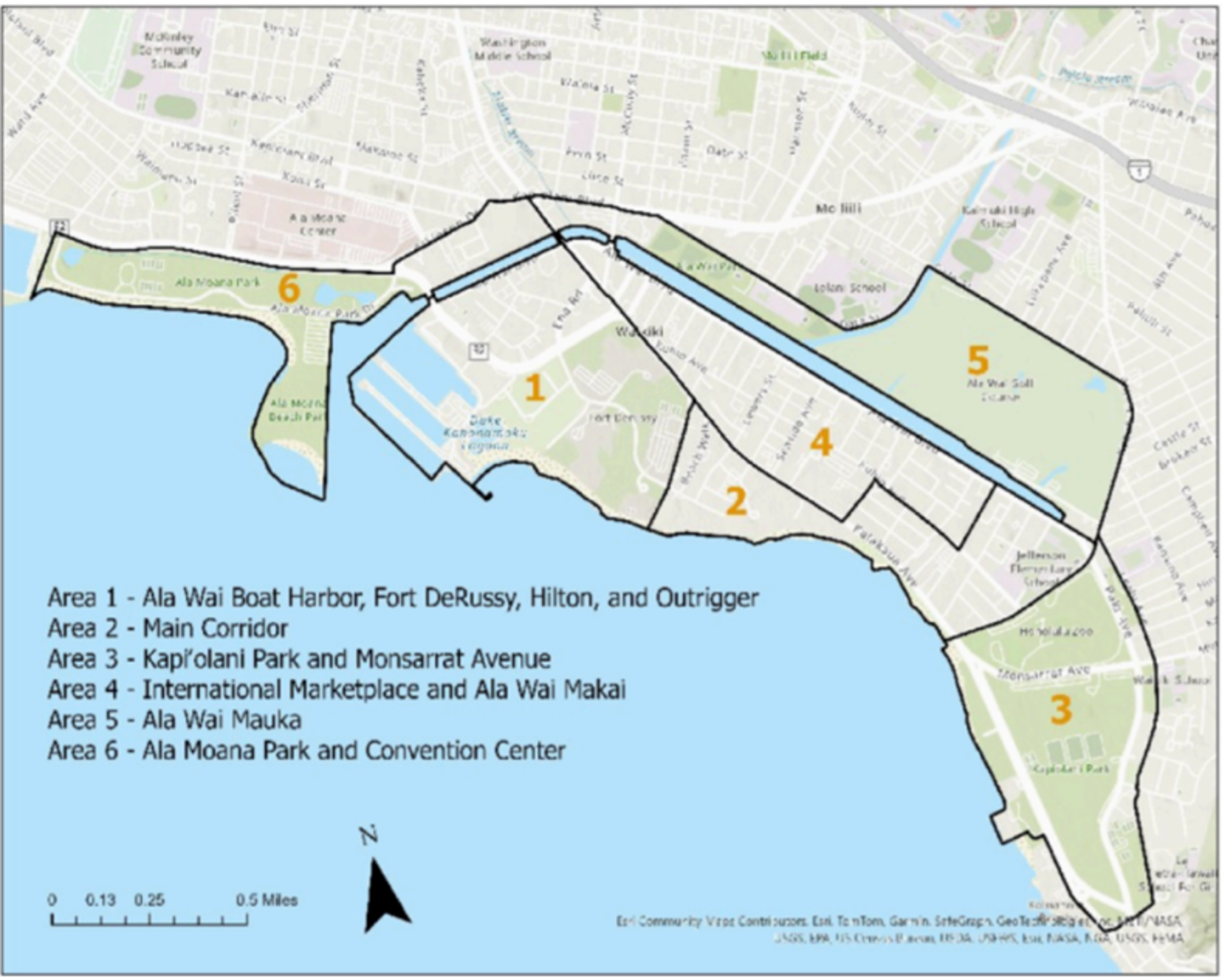

Waikiki, Honolulu, Hawaii, is the main visitor and economic hub on the island of Oahu. For the first 11 months of 2024, total visitor spending on Oahu was $8.25 billion, the highest in the State. The homeless crisis, however, has impacted Oahu, and, specifically, the community of Waikiki. Federal policy that promised to improve outcomes for the homeless population and to transition the unsheltered to permanent supportive housing (PSH) was not delivering. In fact, by 2022, PIT counts along the Main Corridor (Waikiki’s commercial spine where most visitors, businesses, and street activity concentrate) spiked at 111 unsheltered living across the 1-mile stretch, leaving many business and community leaders in Waikiki to wonder what they could do about it.

Building a Solution

Beginning in 2022, the Waikiki Business Improvement District (BID), City, and County of Honolulu launched the Safe & Sound Waikiki Program which, over the course of three years, realized an 18% decrease in crime and a 78% decrease in the unsheltered homeless population. The Waikiki Safe & Sound Program, in just two years, saw 97 unsheltered homeless people placed into housing, with 16 opting for long-term treatment.

These successes are the result of seven primary levers:

- Deterrents and Accountability: The Business Improvement District funds security staff, ambassador teams, and strict enforcement of camping, trespass, and beach closure rules. This creates consistent consequences for chronic offending in Waikiki and has improved public safety.

- Incentives and Exit Paths: Enforcement pressure is paired with clear off-ramps for homelessness like relocation tickets home, shelter placements, respite beds, and other options that make accepting help easier than staying on the street.

- Clinical and Behavioral Health Care: A weekly street-medicine rotation brings physicians, nurses, and insurance navigators directly to the sidewalk, stabilizing people with serious mental illness and/or addiction and reducing dangerous public psychotic episodes.

- Outreach and Engagement: Outreach workers from the Business Improvement District, nonprofit partners, and trained guards acting as informal caseworkers build relationships, coordinate appointments, and consistently offer services to incentivize people to agree to leave the street.

- Legal and Policy Tools: Hawaii’s Assisted Community Treatment (ACT) law, the involuntary hold process, and supportive judges have made it possible to connect dangerous behavior and repeat offenses to treatment, temporary holds, or negotiated relocation agreements.

- Data, Measurement, and Coordination: Detailed PIT counts and referral assessments by subarea and weekly cross-agency meetings allow the city and the Business Improvement District to track displacement, measure progress, and adjust tactics based on real-time conditions.

- Governance and Funding Model: A Business Improvement District funded through self-imposed commercial property assessments, governed by a private board, and supplemented by grants and donations, provides stable support for security, outreach, effective business and community engagement, and clinical partnerships.

Where the Waikiki Business Improvement District is unique is in the granularity of their engagement. Most organizations utilize HUD-funded Continuums of Care (CoCs) reporting metrics (i.e., Point-in-Time (PIT) counts) to analyze performance and root strategic plans to address homelessness in their geographic boundary. Although this data can be helpful at high level, it lacks many key insights necessary to drive practical solutions on the ground. The Waikiki Business Improvement District, as an example, operates within the Honolulu City and County CoC (HI-501), which has geographic boundaries that cover the entire island of Oahu; meaning that reporting is less valuable for their particular district. For Waikiki to achieve their aim of reducing homelessness in their specific community, they needed much more detailed metrics that captured the current state of the problem and a means for tracking the impact of their solutions.

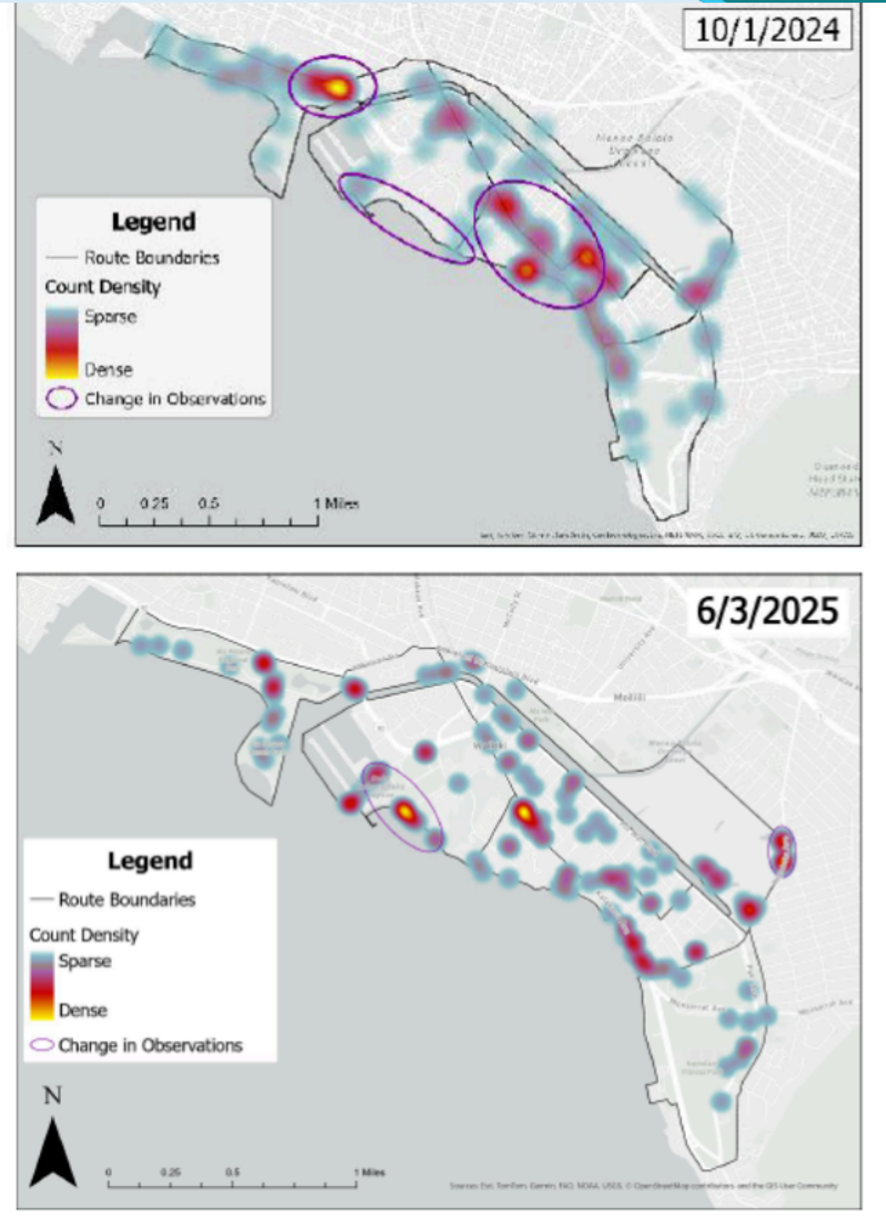

Strapped with smartphones and tablets, the Waikiki team launched an on-the-ground campaign that tracks their community outreach personnel, enables data capture at a district block level, and overlays that data with operational tools that their team uses to track appointment follow-ups, court dates, migration patterns and much more. This level of granularity allows for visuals such as the following heat map that clearly demonstrates population density and migration patterns, equipping Waikiki for program evaluations and solution planning:

Within the operational tools that the Waikiki team uses, they capture the following pieces of data:

- Field activity: outreach contacts, safety tasks, sit/lie approaches (plus compliance outcome where available)

- Coverage: geotagged interaction locations, hot spots, staff route tracking

- Individual continuity: recurring-person case log (encounter history, last seen, engagement vs decline, notes, follow-up needs)

- Profile + service outcomes: veteran/disability flags, local vs visitor, origin region; services offered and accepted vs declined

- Justice + relocation linkage: incident/arrest patterns (repeat offenders); relocation origin/pathway and follow-through

- Clinical data partitioning: medical details (diagnoses, meds, insurance) kept with Waikiki Health, not in the BID system

Waikiki has moved from annual, coarse-grained reporting to frequent, small-area counts that function as an intervention in their own right. Every time they conduct a count, staff are engaging people and recording contacts with security and healthcare partners. Because the data is structured and repeated, it can be mapped to all seven of their policy levers and used to test whether specific changes in security, healthcare access, outreach, or environmental design are reflected in the numbers. In contrast, most CoCs cannot convincingly show that they have reduced homelessness in particular corridors or neighborhoods, because their data is too infrequent, too aggregated, and not directly tied to operational decisions. Waikiki’s model shows what it looks like when data is collected with the explicit intent to guide action and then is actually used to adapt to community needs.

Long-Term Challenges

Speaking with Waikiki Business Improvement District President and Executive Director, Trevor Abarzua, he notes that despite the gains in the core corridor, Waikiki is still constrained by structural bottlenecks. There are still far too few beds across the system (e.g., emergency shelter, detox, medical respite, and longer-term psychiatric and addiction treatment), so short emergency holds of up to 72 hours under Hawaii’s mental health law are but a brief reprieve before people inevitably end up on the street again. Hawaii State Hospital is already running well over its licensed capacity, and the state falls below benchmarks for psychiatric beds, so the most seriously ill people are constantly being shuffled rather than held in treatment long enough to change their trajectory.

Chronic staffing shortages at the Honolulu Police Department (HPD) mean Waikiki Business Improvement District’s (BID) ambassadors and contracted guards are filling street-level gaps that sworn officers used to cover. A steady flow of people becoming homeless on Oahu, including some who have only recently arrived from the mainland, keeps reducing progress. The BID’s tools are effective, but they sit on top of a statewide deficit in treatment and housing capacity that only the city and state can fix.

Recommendations for Cross-Sector Leaders

Looking at the successes and challenges faced by Waikiki, there are several takeaways for private, nonprofit, and public sector leaders to consider.

- First, lean into public-private partnerships using business improvement districts, downtown alliances, and employer coalitions to put real money and management capacity behind homelessness and safety as part of the communities’ strategic economic plan.

- Second, allocate funds towards security and street engagement teams to enforce basic rules, contract with shelter and health providers for outreach and street medicine, align regularly with city departments, and develop a strategy that pairs consequences for repeated criminal behavior with clear pathways into detox, shelter, and housing.

- Third, leverage neighborhood-level data to demonstrate what is working, where people are being displaced, and why further investment is justified.

State and city policymakers should support these initiatives through further investment in infrastructure and legal reforms:

- Fund transitional housing and psychiatric beds at scale so that assisted outpatient-style laws and short-term holds lead to long-term transitional support,

- Expand involuntary commitment processes for people struggling with severe mental illness and substance use disorder,

- Support local campus models that concentrate shelter, treatment, and housing on a single site that police, courts, and outreach teams can reliably use.

Helping this extremely vulnerable population requires an all-hands-on-deck approach and Waikiki is a great example of how quickly dedicated teams can reverse the course of their community.

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about our fight for policies at the state level that restore liberty through transparency and accountability in American governance.