Confronting Regulatory Inertia to Unleash Texas’s Economic Potential

The Problem: Regulatory Inertia

Texas’ free-market constitutional republic is stymied by regulatory inertia—an ever-growing and often incoherent compliance burden that crushes business and erodes legislative authority and judicial review. Texans require a greater and opposite force: bold leaders armed with smart laws designed to restore foundational checks and balances and nurture fair and competitive markets.

In recent years, Texas has positioned itself as a champion of economic freedom and innovation, a rebuttal against states like California and New York, which are increasingly mired in regulatory thicket and bureaucratic bloat. Indeed, with a surge of tech companies relocating to Texas, Lone Star leaders boast a new hotbed for American innovation. Yet, beneath this veneer of prosperity is a labyrinth of onerous regulations and broken regulatory procedures that distort price signals and deter would-be entrepreneurs. In the Cicero Institute’s 2024 rankings of all state-level Administrative Procedures Acts (APAs)—the laws that govern regulatory processes for state-level executive branch agencies—Texas finished 40th, trailing even New York and California. And Mercatus’ 2024 analysis of regulatory restrictions in state codes—instances of restrictive language such as “required” and “shall not”—Texas joined California, New York, New Jersey, and Illinois as the only states imposing more than 250,000 restrictions.

Onerous restrictions and broken procedures result in economic deadweight losses (costs to society imposed by market inefficiencies) and constitutional dysfunction. When unelected and often un-fireable executive branch bureaucrats wield quasi-legislative power, foundational principles of representative democracy break down. Likewise, when aggrieved plaintiffs lack avenues to legal recourse against bureaucratic agencies, and judges defer to agency interpretations of laws, judicial review erodes.

Two academic concepts are useful to understand the regulatory crisis in Texas: first is regulatory capture, second is government failure.

1. Regulatory Capture

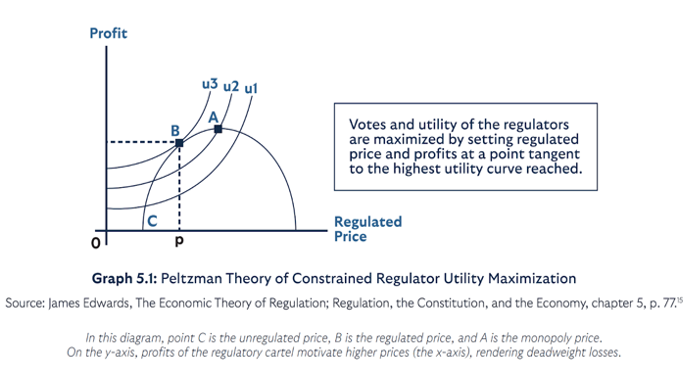

Armed with powers that blur the lines between branches of government, increasingly powerful regulatory agencies become attractive targets to the most powerful industry participants. Rather than sound the alarm about new regulatory burdens, these rent-seeking interest groups advocate for favorable regulations, yielding higher compliance costs for their competitors and deadweight losses for society. University of Chicago Economist Sam Pelzman famously pointed out that profits of this “regulatory cartel”—rent-seeking interest groups and career- or political-minded regulators—catalyze higher prices for consumers. In short, while regular citizens and disruptive founders have access to their elected lawmakers, it is only the most entrenched interests that have access to overpowered regulators, capturing agencies and weaponizing expansive and legally uncontested rulemaking to distort price signals and fortify market failures.

2. Government Failure

Columbia University economist Joseph Stiglitz famously distinguishes between market failures and government failures. Market failures include phenomena such as the tragedy of the commons (when a shared resource is overexploited), monopoly (when one firm dominates market share and ratchets up prices), and moral hazard (when a firm takes excessive risk knowing another party will bear the costs). Government failures occur when bad public policy yields these same outcomes, and, more often than not, perceived market failures are really just government failures in disguise. While Stiglitz is a New-Keynesian who sees more market failures than government failures, his concept provides a useful prism to understand the contours of burdensome regulation.

In Texas, onerous and unaccountable regulatory activity tends to yield government failures that masquerade as market failures. This then invites more regulation in a feedback loop that entrenches and expands deadweight losses. At the national level, one Mercatus analysis found that government regulatory failures were responsible for an approximately 25 percent smaller economy over a 40-year period. In Texas—burdened with 274,469 regulatory restrictions, the fifth most of any state—it is reasonable to expect that citizens currently endure a similar outcome of stolen growth.

The Solution: A Greater and Opposite Force to Confront Regulatory Inertia

Fortunately, the regulatory crisis in Texas is addressable. Bold and forward-thinking policymakers can emulate deregulatory leaders and implement straightforward but meaningful reforms that confront regulatory inertia, strengthen foundational checks and balances, and propel innovation. Specifically, the Cicero Institute advocates for a menu of reforms that nurture free market corrections and strengthen foundational checks and balances.

1. Nurture Free Market Corrections

A. Implement Rigorous Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA)

The Texas APA currently only offers vague language requiring “economic impact statements” and “regulatory flexibility,” and the quality and robustness of these documents vary widely by regulation and agency. Ambiguities in existing language grant regulators discretion to manipulate analyses, conflate market failures with government failures, and circumvent the public will and interest.

Texas lawmakers should amend Section 2006.002 of the Texas Government Code to strengthen CBA requirements and ensure:

- Transparency and Accountability: Mandate that the total projected benefits of any rule exceed its projected costs across multiple time horizons.

- Public Access to Data: Require all data and methodologies used in analyses to be publicly available online, searchable, and machine-readable.

- Legal Standing to Challenge: Create standing for stakeholders to challenge the validity of rules solely based on inadequate or procedurally noncompliant cost-benefit analyses.

Texas would jump eight places in Cicero’s APA rankings if it implemented only these robust CBA requirements.

B. Automatic Expiration of Rules

The Texas APA currently calls only for periodic review of rules by respective agencies, and the Texas Government Code (Chapter 325) enacts agency sunsets, allowing for rule deletion only when agencies are abolished. Unsurprisingly, agencies rarely advocate for their own elimination, and rules in Texas thus tend to exist on the register in perpetuity.

The Texas legislature should amend Section 2053, ensuring automatic expiration of every rule eight years after its initial promulgation. If agencies wish to retain a regulation, they should have to fully re-promulgate, going back through the notice-and-comment process to consult businesses and adjust rules based on insights from the past decade of enforcement.

Texas would jump 17 places in Cicero’s rankings if it implemented only this reform.

C. Freedom to Challenge

The Texas APA specifies that actions for declaratory judgment on the validity or applicability of a rule must be brought only in a Travis County district court. For the 29 million Texans who do not live in Travis County—many residing hours away—this provision effectively blocks and deters legal recourse in cases of agency abuse.

Legislators should amend Section 2001.038 to enable Texans to challenge agency rules in their home county or in the county of their principal place of business, whichever venue is most accessible.

Texas would jump 17 places in Cicero’s rankings if it ensured freedom to challenge.

2. Strengthen Foundational Checks and Balances

A. Executive Branch — Gubernatorial Oversight

Texas endures one of the largest and most byzantine administrative systems in the country: more than 150 permanent agencies and nearly 200,000 full-time employees (350,000 when including higher education). Consequently, it is often challenging for the Governor to exercise the public will in managing the bureaucracy. Many regulations are issued without the Governor’s awareness or approval, leading to dissonance within the executive branch.

Texas should establish a Virginia-style Office of Regulatory Management (ORM), composed of political appointees who:

- Oversee the bureaucracy and ensure alignment with the Governor’s agenda,

- Report directly to the Governor,

- Set performance metrics for agencies, and

- Vet and reject unnecessary regulations.

The Governor should act as the CEO of the executive branch, serving the interests of the “shareholders” (voters) with a highly capable “C-suite.” Implementing an ORM equips the Governor with the necessary tools to manage the bureaucracy efficiently, ensuring that executive actions reflect the will of the people.

B. Judicial Branch—No Deference Without Delegation

While the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the Chevron doctrine in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, the holding was statutory and not Constitutional and, therefore does not apply to state-level agencies and state-level courts. Texas courts have a mixed record on deference—sometimes deferring to agencies, other times reviewing de novo—but the bias tends toward deference. In Railroad Commission v. Texas Citizens for a Safe Future & Clean Water (2011), the Texas Supreme Court echoed Chevron, ruling that Texas courts should defer to state agency interpretations if statutes are ambiguous, and agency interpretations are reasonable. This precedent leaves Texas in an awkward legal limbo in the Loper era.

Texas leaders can resolve legal uncertainty by passing a law that requires state courts to exercise de novo review in cases of contested regulations and prohibit deference to agency interpretations of statutes. Texas can emulate several states:

- Delaware, Florida, Arkansas, Nebraska, and Idaho require de novo review of agency rulemaking.

- Kansas, Utah, Arizona, Mississippi, and Wisconsin prohibit deference to agency interpretations without explicitly requiring de novo review.

- Michigan, Ohio, and Indiana have removed previous mandates requiring courts to defer to agencies.

C. Legislative Branch—No Regulation Without Delegation

Regulators frequently promulgate rules without explicit statutory delegation, sometimes without citing any statute or referencing statutes no longer in effect. Deference exacerbates this problem by effectively overriding the legislature and giving agency justifications the force of law.

Texas lawmakers should enact legislation that explicitly ties regulation to express delegation.

- Require agencies to regulate—and courts to defer—only when delegations are express and specific.

- Prohibit agencies from regulating—and mandate courts to strike down regulations—when statutory delegations are implicit, or statutes are silent.

- Require agencies to obtain legislative approval for regulations derived from general and hybrid delegations (ambiguous language).

By strengthening legislative oversight, Texas can reassert the primacy of its elected representatives and the voice of its citizens in the lawmaking process.

Conclusion

Prosperity and human flourishing arise when free societies empower individuals and businesses, not when innovators are restrained by layers of unnecessary and outdated regulations. Texas is an economic powerhouse, but regulatory overreach in the status quo leaves growth and innovation on the table. It is time for bold leaders in Texas to unlock the Lone Star state’s full potential by decisively confronting regulatory inertia. By embracing The Cicero Institute’s reforms, Texas can restore foundational checks and balances, cultivate fair and competitive markets, and unleash unprecedented economic growth.