Competitor’s Veto is Strangling Healthcare

Should existing hospitals be allowed to block new healthcare services from entering the market? Protectionism violates the core principles of a free economy, yet this is happening in New Hampshire. The Granite State currently allows hospitals to shut down facility licensure for six essential healthcare services, limiting access to care for New Hampshire residents.

New Hampshire bill HB 223 sought to eliminate the protectionist policy during this last legislative session, but it ultimately failed to pass in both chambers. The consequences are clear when we look at similar policies, like Certificate of Need (CON) laws, which decades of research show reduce access, drive up costs, stifle innovation, and worsen health outcomes, especially in rural areas.

In states with certificate of need laws, new facilities must prove a “market need” to open. The burden of proof is difficult to demonstrate, especially for smaller businesses seeking approval. Often, existing competition retains a “competitor’s veto” and can deny CON applications.

In 2016, New Hampshire swapped its CON process for a “material adverse impact” policy that shifts even more power to hospitals. Instead of a third-party board that approves or denies applications, New Hampshire grants the power directly to existing competing critical access hospitals. Though opponents of HB 223 denied similarities between CON law and material adverse impact, the former chair of New Hampshire’s CON board confirmed that, in principle, they operate in the same way. Additionally, researchers of CON laws have begun classifying New Hampshire as a CON state in datasets since the material adverse impact policy bears the same impact.

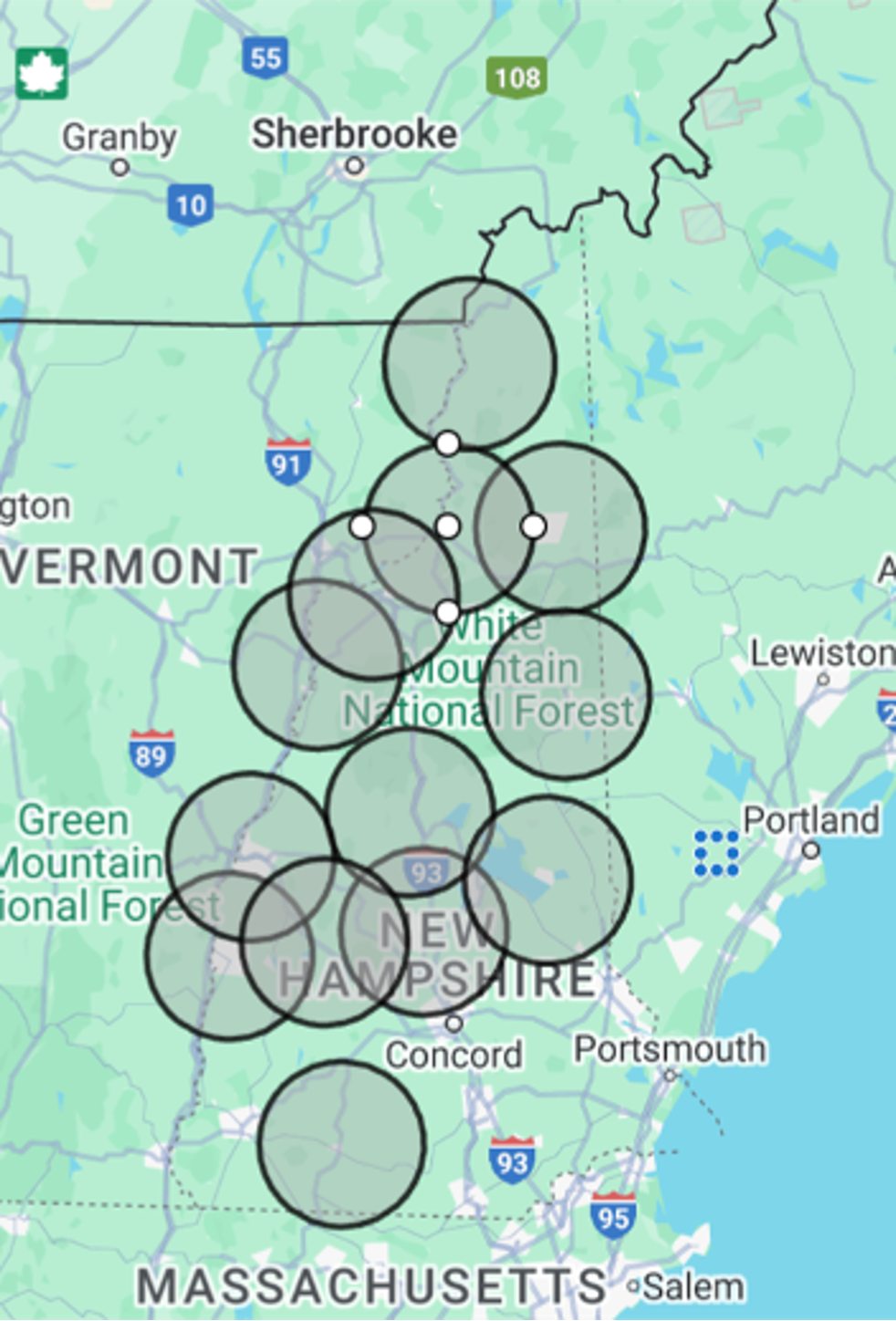

One key difference between material adverse impact policies and CON laws is the geographic distance requirement. Where CON typically encompasses a whole state, material adverse impact only applies if a new health facility wants to open anywhere within 15 miles of a critical access hospital.1 Yet this still impacts the majority of the state. Thirteen types of healthcare facilities must provide notice, and hospitals are allowed to object to six types of those facilities. Let’s look at the reality of those laws.

The center of each gray circle represents a critical access hospital in New Hampshire. If a new health facility wants to open anywhere inside the circle, it must notify the hospital(s) within that area.

When the notice requirement is paired with the “material adverse impact” clause, it allows a hospital effectively to shut down licensure of the proposed new facility. All the competitor hospitals must do is file a report that the new facility would impact market share, utilization, patient charges, referral sources or patterns, or personnel resources, even minimally. Once the hospital’s report is reviewed, the new health facility can no longer apply for licensure. Though the new facility can appeal, the hospital can counter-appeal as many times as it likes to block out the new providers.

The material adverse impact clause applies to six types of healthcare facilities: ambulatory surgical centers, birthing centers, educational health centers, dialysis centers, new hospitals/specialty hospitals, and walk-in care centers. It is safe to assume that the hospitals will want to expand this authority to more facilities and more hospitals in New Hampshire because it will allow them to consolidate a greater share of the healthcare market. Critical access hospitals effectively hold a monopoly on healthcare services in rural regions. For example, New Hampshire has 31 licensed ambulatory surgical centers, yet only one of the licensed ambulatory surgical centers is within a 15-mile radius of a critical access hospital. In other words, critical access hospitals are likely blocking competitors from providing that service, which decreases access and increases costs.

If New Hampshire wants to improve access to healthcare and reduce the price of services, it should remove this unfair statute from state law and all material adverse impact requirements in the administrative codes for facility licensure.

To ensure that existing health care providers cannot swap certificate of need or material adverse impact policies with other similar schemes, representatives in states with recently repealed certificate of need laws should consider passing legislation that explicitly prevents existing health care systems and providers from having a say over whether new healthcare facilities and services can provide care.

[1] Created using the map developers’ circle tool and the addresses of New Hampshire’s critical access hospitals. See https://mapdevelopers.com/draw-circle-tool.php and https://www.dhhs.nh.gov/sites/g/files/ehbemt476/files/documents2/licensedfacilities.pdf

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about our fight for policies at the state level that restore liberty through transparency and accountability in American governance.